South Korea Week: BYUN SoonChoel: Eternal Family

Byun SoonCheol is one of leading Korean portrait photographers.

In the history of Western culture, portraits have been an important tool for revealing the status, power, and wealth of European nobility and bourgeoisie. With the invention of the camera, this role of portrait became the main use of photography, replacing painting. In addition, portrait photography has more meaning than simply targeting each individual merely as a subject matter. It has played an important role as a medium representing each era, society, and culture.

In this respect, for Byun SoonCheol, a person is more than a simple subject of photography. Byun’s portrait series represents an era as well as socio-cultural trends.

The Eternal Family series introduced this time is meaningful in that the artist tried new techniques in sociological methodology along with the typological portrait photography he has been continuously pursuing.

Eternal Family is not just a family photo.

Due to its historical characteristics, Korea has the agony of displaced families from the North and the South left by the great scars of the Korean War. Families who have been separated due to the Korean War are passing away without managing to meet each other alive. In other words, the generations who experienced the war are gradually disappearing into the history of time. Generations living towards the future in this reality will no longer even remember the agony of being a displaced family.

At this point, photographer Byun SoonCheol’s Eternal Family series has several significant meanings.

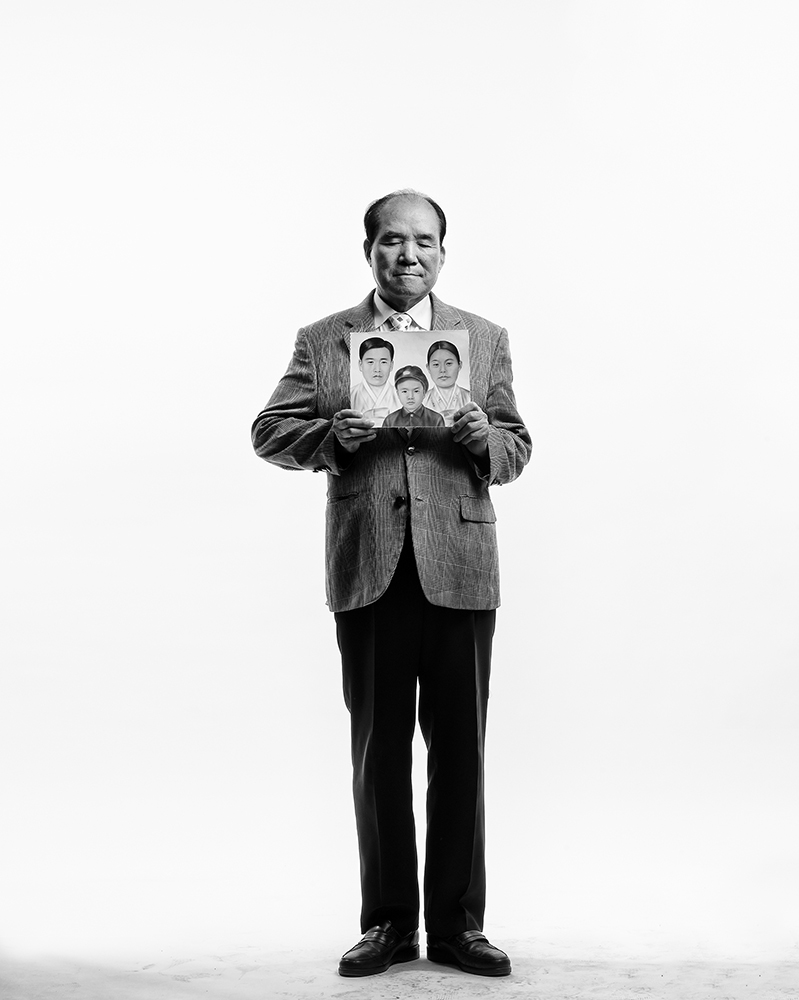

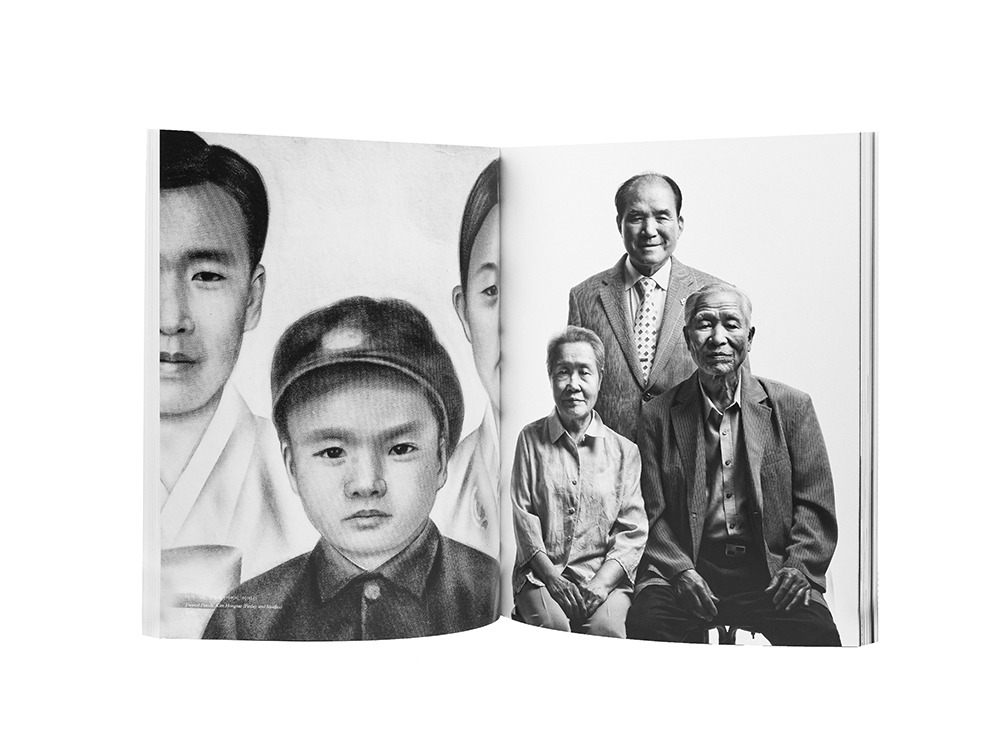

In this series, Byun is dealing with a certain kind of family: the displaced family. As the only divided country in the world, Korea still suffers from the pain of separation (due to the war) in many families. While methodologically based on typological portrait based on the historical issues of displaced families, it is groundbreaking that new technology was introduced into photography as a means of contemporary bonding. Family gatherings of virtual figures were created technically in the space of photography by using ‘3D age transformation technology’ in the old photos.

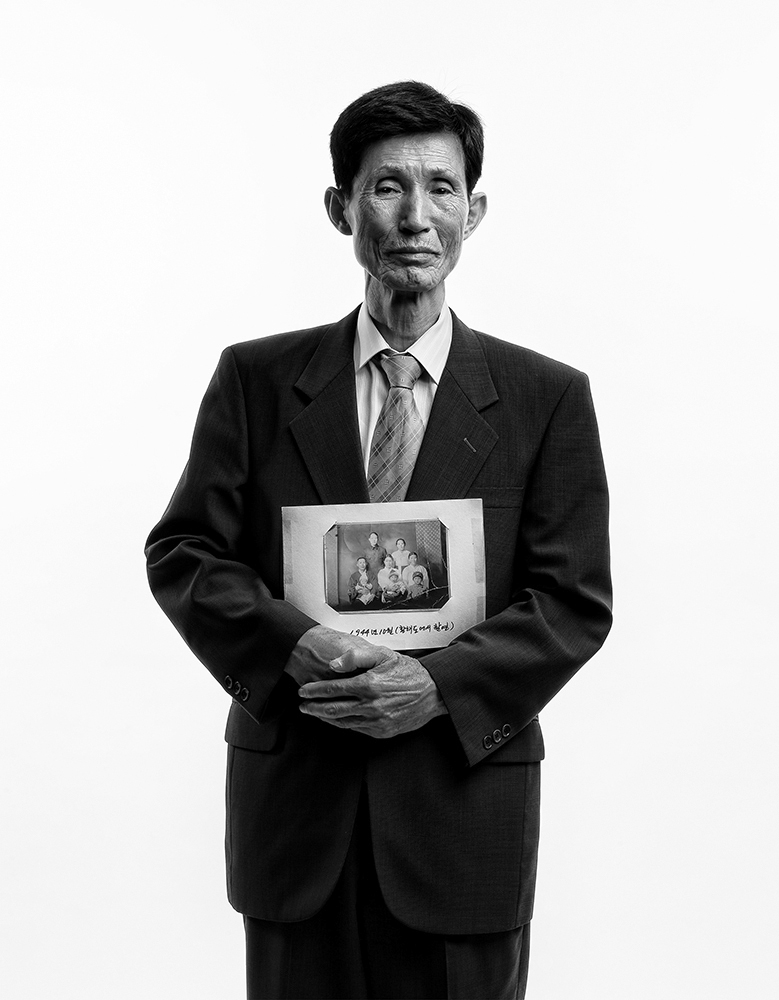

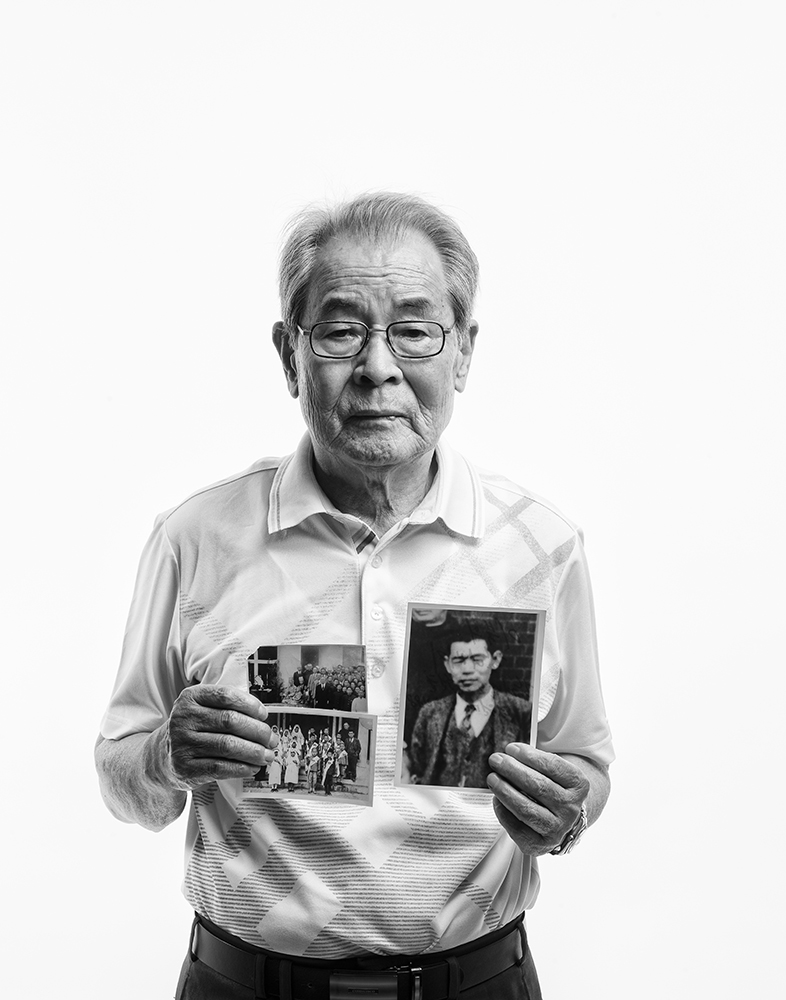

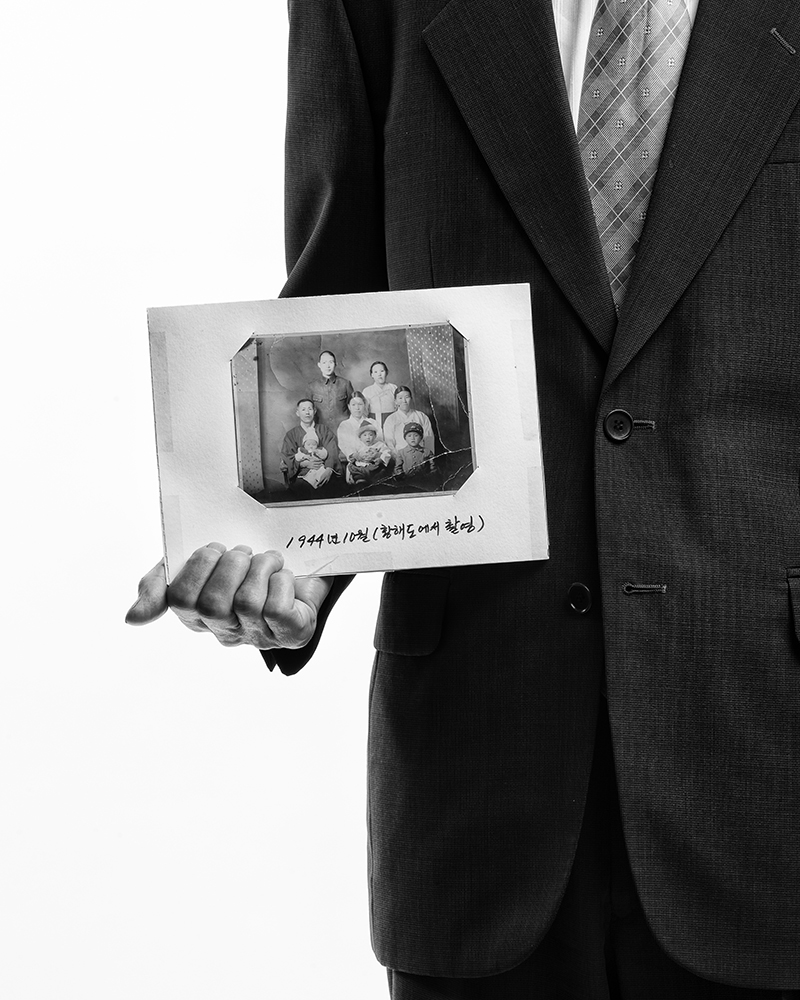

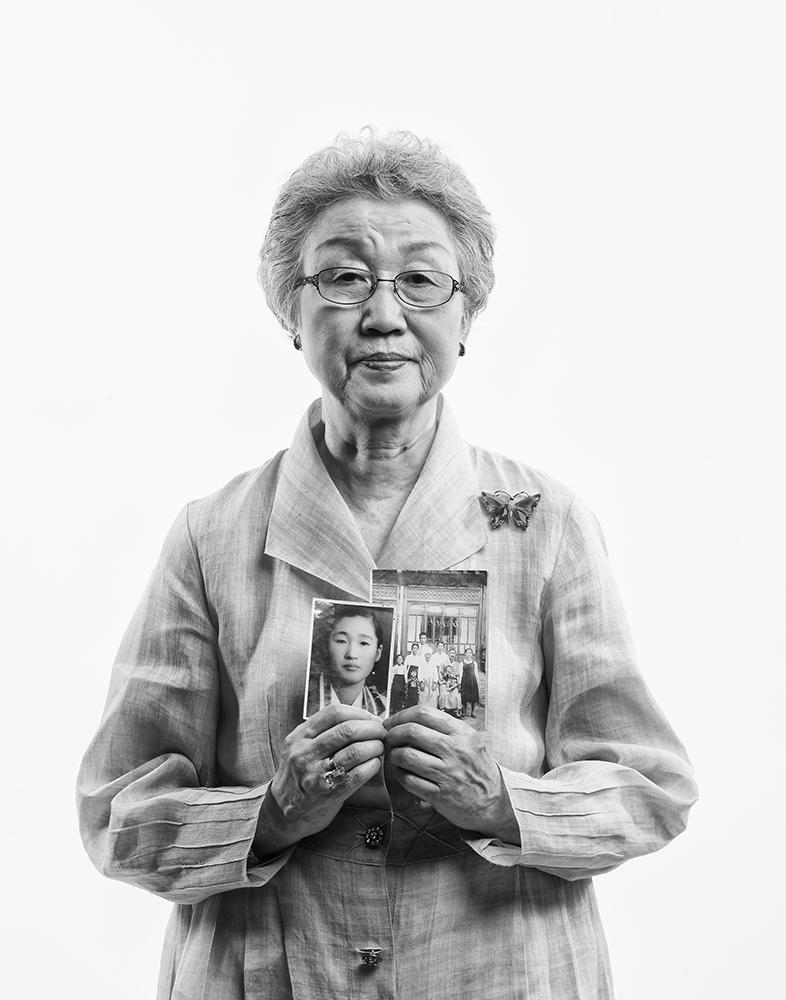

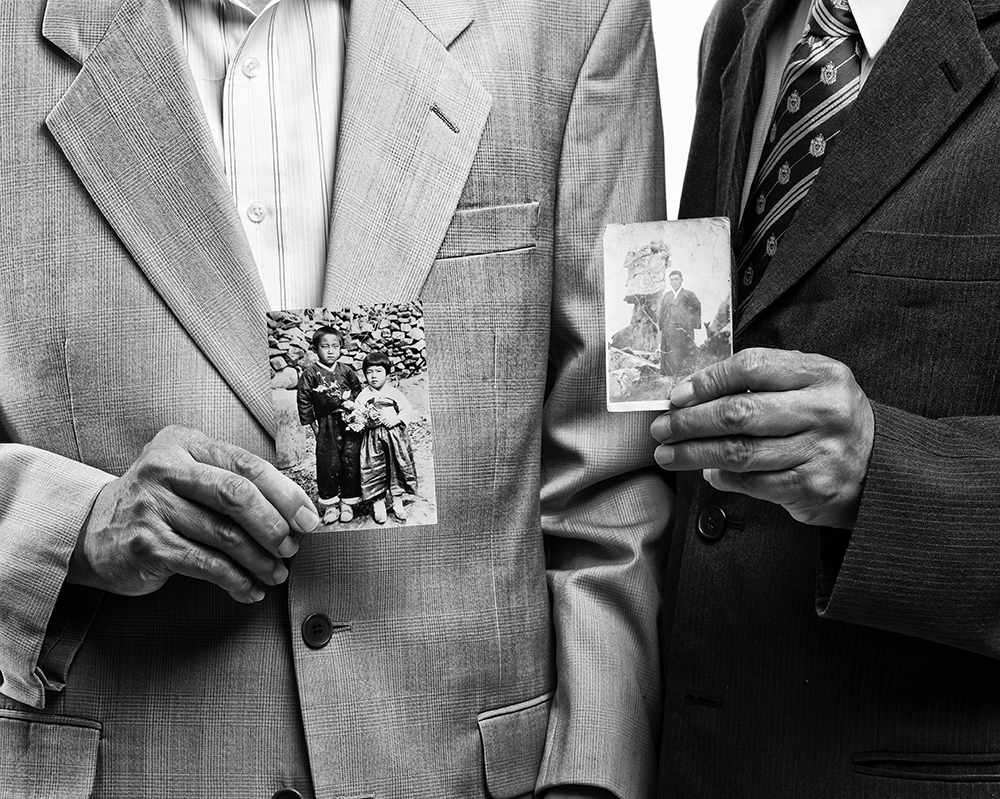

This photograph of a father in his 80s and his son, who has grown old in his 60s, standing side by side is not a family photo taken at the same time in the same space.

This is a current family portrait of a father from North Korea and his son from South Korea, who were separated 70 years ago during the Korean War and have never met again for the rest of their lives. The 80-year-old man on the left is a figure digitally imagined what he would be like if he were still alive.

The production method of this series was to first find people who kept old photos of their families left in the North among the displaced families. Currently not many people are still alive, but the artist has found a few who remain. This is a family photo created by using ‘3D ages conversion technology’ by extracting the imaginable current faces of the North Korean family members from 70 years ago photos provided by the displaced people at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) Imaging and Media Research Center after photographing them one by one.

“I named the photograph series ‘Eternal Family’ instead of ‘My Family’, thinking that families are eternal and cannot be separated even if physically displaced.” – BYUN SoonChoel

Please explain what triggered your interest in photography and motivated you to work as an artist. (For example, if you chose photography as your major, the reason or events that led you to do so.)

There was a time when I was hospitalized for a long period due to a tragic accident during the military service. At that time, my older brother gave me a history book related to photography, and that made me come to this point. For a long time, I have been working with only ‘portrait’ photos out of my curiosity of the world and to capture the essence of human beings. The major series include New York, Couples, National Song Contest, and Eternal Family.

Your various photograph series mainly contains the figure of a person. Do you have any specific intention or reason to make artistic photography through a person in particular? If yes, please explain in detail.

Personally, I think there is a part that comes to my mind naturally when looking at an object, just like good music naturally reaches your ears and heart.

In other words, my work implicitly contains exhaustive inquiry, questions, and answers about the essence of human beings, just as humans and communities are continuously in an inseparable relationship with each other. That’s probably the biggest reason I do portrait photography.

Also, rather than looking for someone who meets certain criteria, and rather than looking at the surface captured in the viewfinder, I often model someone who looks special in front of the viewfinder even though he or she has an ordinary appearance. I don’t have a clear idea that ‘it should be just like this’. However, as the saying goes, ‘Eyes are a person’s heart’ and ‘Eyes are windows to the heart’, it seems that I pay special attention to the people’s eyes. The act of taking a picture takes place within one millionth of a second, and I believe that a dense communion between the photographer and the subject occurs during that short period of time, which is an area that cannot be tangible. Sometimes I can see the ‘room’ that Roland Barthes was talking about, and in many cases I am visualizing it.

Have there been any changes in your work in the US and after returning to Korea? If yes, please describe the process and content of the changes in detail.

The general context of my work hasn’t changed. The fundamental questions and answers to inquire and understand the essence of a subject have always been the same. However, the New York and Kid Nostalgia series while studying abroad gradually expanded from the personal exploration of self-identity to the social realm. There are Interracial Couple, National Song Contest, and Eternal Family series. The Eternal Family tells the story of the pain penetrating the dramatic history of modern Korea. Everyone who has lived in Korea’s modern society possesses their own pain, but among them I focused on the pain of the displaced people who live with the scars left behind by the tragic fratricidal war. I believe that one of the most important media for capturing memories is photography. So, as a photographer who deals with photos and memories, I engage in my work considering how to achieve artistic sympathy with the displaced people.

The Eternal Family series was produced in 2015, the 70th anniversary of Korea’s liberation. In the context of rapidly changing visual arts, the recording nature of photography and its social characteristics have been colliding as well. In some cases, such clashes exemplify the direction of modern society, but personally, I remember that when I was working on Eternal Family, I focused on how to combine virtual and reality to make resonance in one’s heart. What’s important in this series is to deal with the issue of displaced families in Korea and the story of the elderly displaced people by juxtaposing virtual and reality. Families that had to be separated during the war, and the pictures of the families that were brought with them when moving to the South… I worked with those small photos. With the help of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) Imaging and Media Research Center, a 3D age conversion program was used to enable displaced seniors to be reunited with their families that they could only see in their dreams in a space where virtual and reality were mixed. Elder Yoon Byungguk, who served as a model for the work, lingered around the exhibition hall for a long time, saying, “Mother and father are over there, how can I leave the exhibition hall?” even though this is a virtual picture, that is, a picture that is not real. It was a touching yet heartbreaking experience. Looking at the eyes of the elderly who couldn’t leave the exhibition hall, I was asking myself: doesn’t the truth take precedence over art in the end?

Please describe the work Eternal Family.

The biggest pain in the series comes from the forced dissolution, separation, and annihilation of the smallest member of society due to the external element of war, which has nothing to do with the individual will. The image shown through KIST’s age conversion technology is, after all, an illusion and virtual. The appearance of the ‘family’ reconstructed through images created with the old photos of the whole family left in the North may be a bit questionable to those who see the work without knowing the story behind it. It can be taken as just a black-and-white photograph of older people. The distinct power created by these sources, such as displaced families, virtual families, reconstructed families, and families whose life or death is unknown, is a significant part of the work. It contains the emotional confusion and sadness that I felt when listening to their personal stories. The mothers, fathers, and brothers and sisters who are living apart and became old being unable to see each other due to the external forces were reconstructed by combining the images in a single photograph taken by the artist. The appearance of the family in the virtual photo, where separated families meet as a whole family, gives a momentary touch with comforting and consoling atmosphere. Even if, in the end, they will be disappointed in the fact that this cannot be realized in reality, and the longing for reunion will grow stronger, it generates a magical power for a moment in the form of photograph. It reminds people living in the present that there exists families around us who are living in sorrow and pain. Aside from the technical aspect, the word “family” was sometimes expanded to a different form than the previously indicated, and sometimes its original meaning was faded and diluted. I believe my work can throw essential messages of human being just by serving as an opportunity for viewers to think about the meaning of family for a moment and to be aware of the fact that there are people suffering from the pain of division that is living and breathing in our history.

Is there a topic that runs through your whole series or has continuity in relation to them?

My work is, after all, an extension of the process of asking and answering individual questions to the realm of society. Continuous curiosity about the world and fierce contemplation about relationships are contained in various series. The topics of portraits are all different, but the underlying meanings are all connected into one: the individual and society are not different. In other words, you and I and the world are intimately connected. The New York series was a time when I was thoroughly recognized as an outsider in an unfamiliar space while studying abroad and found myself in the form of a border liner. The Couples was a process of recognizing our perspectives on multiculturalism and the fact that we are not different from others. In National Song Contest, ordinary people with various appearances look somewhat clumsy and ridiculous on a horizontal stage, but that alone showed the courage and passion to throw off the vertical sternness, titles, and masks that are formed in society. How can Eternal Family empathize with the sorrow and pain of humans in this context? I speculated about it, and came to include the displaced families, the traces of the heartbreaking war in our country, as a reunited family. In the end, I wanted to capture the interest and affection of the essential part of human beings in the whole series.

Critics:

“Family portraits have long served as documentation and evidence of blood ties. Whether taken at home or at a formal studio, family portraits prove that the people within the frame existed together at the same place, at the same time. The special connection between the subjects is confirmed yet again through the sense of affinity the photo imparts – affinity in the sense of visual and biological resemblance rather than Wittgenstein’s notion of family resemblance. Family portraits show how the familial lines flow through the face, body type and build, and how they are inherited and distributed.

Family portraits have existed in the past. They are still taken nowadays and will continue to exist in the future. Of course, photographers seldom select entire families as their subject matter, with rare exceptions such as Thomas Struth’s family portraits. Byun SoonChoel’s imaginary family portraits of the displaced therefore stand out among their kind.

In the Korean context, ‘the displaced’ refers to those who left their home in North Korea and came to the South as war refugees. The literal meaning of the word implies the complete loss of home, but the contextual reference gestures to war-torn diaspora. Statistics vary, but certain records suggest that there are over 8 million displaced including second and third generations, while other documentation offers smaller numbers. The key issue at stake, however, is not the exact count of displaced people but the political circumstances surrounding the transplantation; the impossibility of reconnecting with family back home, unless through rare and special occasions arranged by the government.

This is where Byun enters the scene. He helps these families reconnect across the political chasm through his photography. Of course, the process was by no means simple. The first step was to secure a corporate sponsorship based on the concept. Then, he recruited volunteers with the help of various organizations. The Red Cross, in particular, reached out to two thousand displaced family members who had shown stronger initiative to reconnect with their lost family, such as participating in video message projects. From the volunteers, Byun selected those who had family portraits. Only about one percent of the group qualified, since preserving and keeping decades-old photographs was no easy task in and of itself. Byun tried to photograph them at their homes, but in the end, he invited them to his studio to maintain a sense of consistency in the series.

Meanwhile, Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) digitally converted the old family portraits. Their Center for Imaging Media Research’s ‘3D aging technology’ was developed in 2014 to help solve cold cases or find lost children. Using a database of Korean facial structure and other traits, the program analyzes each subject’s facial features such as the wrinkle volume, partial characteristics, skin thickness, and countenance, and applies the results to montages with a reported precision rate reaching up to eighty percent. The program transformed young girls and boys into old women and men. Young parents were able to stand side by side with their aged family members across the uncrossable border.

The body portions of the portraits were taken from photographs of other models who were of proper age, recorded at the studio. The bodies were then attached to the faces to complete the absent family member and the photograph. In total there were twenty-three subjects.

The people in the photographs stand side by side with their faraway family, having gained sixty or even seventy years in their virtual age. The resultant images are digitally rendered, virtual outcomes. Still, the artists assert that just like any other image, the image of the family exerts a magical power. One person, he recalls, even ‘commuted’ to the studio almost every day, saying that he couldn’t just leave his father in there without looking in on him.

The photographs have, as Vilém Flusser would say, entered the state of pataphysics – an uncanny state where virtual images mingle with the real and become indistinguishable, resulting in an uncanny overlap. The end product’s resemblance to the real deal cannot be objectively verified. However, it serves as an effective substitute for the displaced who wants such a photograph. Psychologically, one could even say the virtual photograph is no different from the real. The photographs are indeed uncanny. Almost but not quite, the virtual comes infinitely close to the real while the real becomes defamiliarized, their uncanniness unapologetically demonstrative of its power in that process. The faces and bodies carry a compelling verisimilitude, presented in a natural scale of black and white. Still, the uncanny feel of the composite portrait persists – perhaps, this uncanniness is itself part of the photographs’ powerful appeal. Just as an ethnically homogenous people form an imaginary community, biologically connected families are also imaginary communities of a kind. Family structures were born out of the process of distinguishing the public sphere from the private, and families are built upon intimacy and privacy. Family ties are biological but also social, governed by social order; the society cannot be sustained should it rely on the closed-out units of biological families alone. The concept of family is historical in nature, and the conventional family structure is undergoing dissolution. Even close family members seldom see one another these days; we all live apart congregating only in virtual spaces like shared chatrooms. Virtual families could serve as surrogate for real ones, but even this option is predicated upon the preexistence of an actual family. Displaced families are wounded families. They carry the trauma of loss and absence and attempts to resolve this hurt take various forms such as attempts to dress the wound. Byun’s virtual family is one such attempt. The virtual family portraits are exhibited as works of art, but also kept as precious embodiments of memory by the displaced.

These two different uses push us to question the identity of photography once again. Which is more significant? Which is the more fundamental use? Such questions overlap with questions of family, prompting us to devise virtual alternatives to the photograph. The photograph, in this sense, is no longer proof of the real but a mechanism of realizing the desired unreal. As is the case with all images, the photograph has served this function since its inception. However, the advent of digital photography has not only changed the process of taking a photograph, but also reconfigured the very definition of photography, enabling the ‘surreal’ in a way that differs from the vision of surrealism.

The state wherein this surreality pervades and combines with the real is what Vilém Flusser calls ‘Techno-bild.’ The digital image, as a form of technological magic, has exerted its powers more in the realm of the real than it has in the realm of art. Even before artists picked up on this potential, Korean plastic surgery advertisements showed off their uncanniness on subway billboards. Not only photographers but art itself lagged, trailing at the heels of the real. The avant-garde function is lost. Byun’s virtual family is a touchstone of photography’s capacity, potential or even role in the digital age. No one can guarantee what the answers to these questions would be like, for practical applicability does not warrant artistic integrity and vice versa.

Byun photographed his subjects from the front. As seen in family portraits, this pose is optimal for illuminating the subject’s identity. The photographs retain the customs of portrait photography while also stepping away from such conventions. Poses are always performative to some degree or another; they are directed and guided based on certain scenarios, and require proper costumes, props, and makeup. Some people stand erect with their virtual families, while others hold hands or caress shoulders. But these postures are also virtual. The term virtual here means that the photograph has lost what is treated as a part of its general identity, its index.

In other words, the photographs are no longer objective traces of light. As reality-based digital montages, the photographs may be, in Hal Foster’s words, a collection of traumatized subjects. According to Foster, the modern heroic subject is now gone from contemporary art, replaced by traumatized subjects. Byun’s family could be a collective of such traumatized subjects. Of course, the traumas are the result of our history and war, both Korean and of the world, and it seems no one can escape from that.”

–article from <constructed Faces, Imagined Families> by Kang Hong Gu (Artist, Director of GoEun Museum of Photography)

BYUN SoonChoel received B.F.A. in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York, and awarded the FGI Year of the Photographer, Korea (2000), John Kobal Photographic Portrait Award, UK (1999), and Piea International Photo Competitions, USA (1998). BYUN held solo exhibitions at Sungkok Art Museum (Seoul, Korea), The Korea Society (New York, US) in 2020, GoEun Museum of Photography (Busan, Korea) in 2018, Asia Culture Center (Gwagju, Korea), Kumho Museum of Art (Seoul, Korea) in 2016, Insa Art Center (Seoul, Korea) in 2015, Seoul Museum of Art (Seoul, Korea) in 2014, Space DA (Beijing, China) in 2008, and SSamzie Gallery (Seoul, Korea) in 2005. BYUN participated in numerous group exhibitions and festivals, which including Asia Publication Culture & Information Center (Paju, Korea) in 2018, Korean Cultural Center (Brussels, Belgium) in 2017, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul, Korea) in 2016, Seoul Museum of Art (Seoul, Korea) in 2015, Somerest House (London, UK), National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts (Taiwan) in 2010, Dali International Photo Festival (Dali, China), Risweyi International Photo Festival (Risweyi, China) Lianzhou International Photo Festival (Lianzhou, China) in 2009, and Art Sonje Center (Seoul, Korea) in 2007.

Sunjoo Lee is a mixed media photographer based in Seoul, South Korea.

Lee’s extraordinary artistic sensibility that was once portrayed through her voice is now visible through the works portrayed through her camera lens. Her photography focuses on a unique lyrical journey into her personal life. She explores her past, present, and future world in a temporal and spatial perspective.

She received a BA in Music from Ewha Women University, a second a second BA in Photography from Chung-Ang University (Academic credit bank system), and an MFA in Plastic Art & Photography from Chung-Ang University Graduate School of Photography in Seoul, Korea. In 2019, she was awarded into the 11th cohort for the prestigious artist residency program at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary Art. Through this residency, she’s currently working on her upcoming series.

Lee’s acclaimed works have been exhibited widely throughout the years in South Korea. Most recently, she had her solo exhibition at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary art, Gwangju Korea. She’s also showcased at Gallery Now, Gallery Gong, Gallery Guha, and more in Seoul, South Korea. Her works are permanently displayed at the Haslla Arts Museum (Gangneung, Korea), and YoungWol Y. Park (Youngwol, Korea).

Her work at large, incorporates everyday objects and subjects to make visual sense of the complexities of human emotions and feelings derived from the intangible, such as music. Her photographic inspiration stems from her experiences of living and travelling abroad. She extracts the memories and various emotions born out of the human connections she’s made during that time of being in foreign spaces.

Building on this conceptual narrative, her work has landed her multiple recognitions, from the 2019 Critical Mass as a top 200 Finalist (USA) to the 1st Place Richards’ Family Trust Award during the 25th juried show at the Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, USA). In Korea, She received a growing up artist award at the Dong Gang International Photo Festival and Now and New Exhibition award at Gallery Now in Seoul Korea. Follow Sunjoo on Instagram: @sunjooleephotography

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026