South Korea Week: Hwang Gyutae: Reproduction

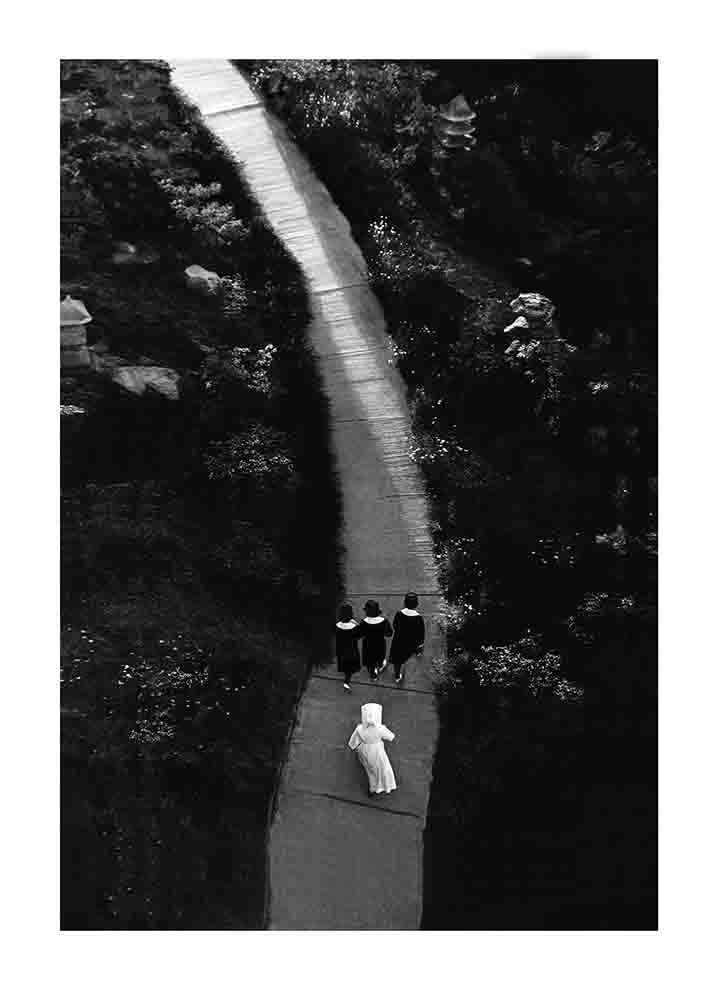

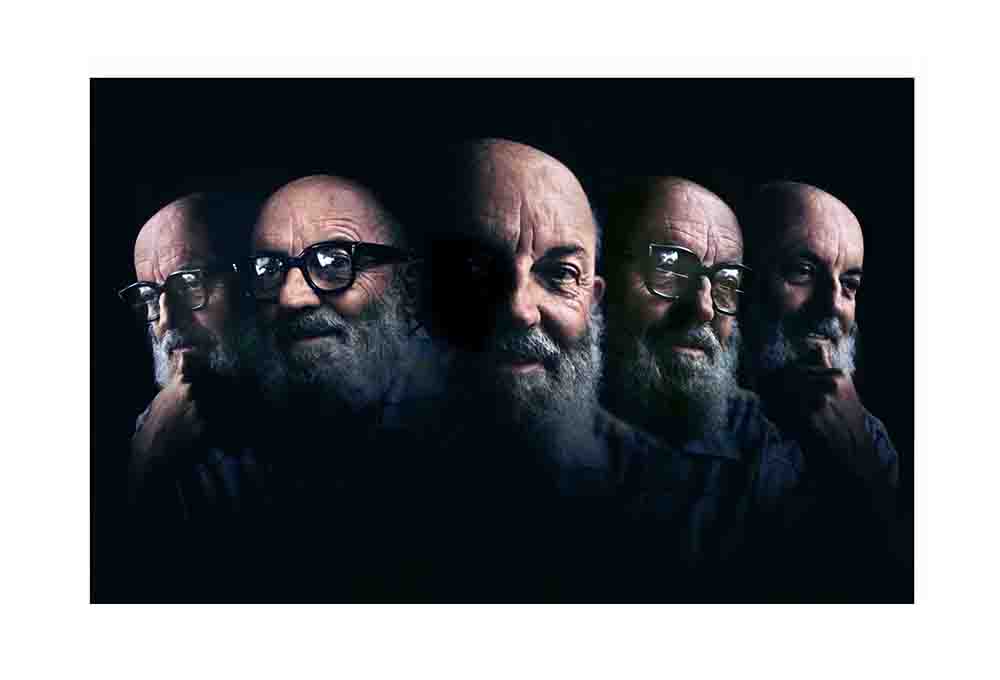

Photographer HWANG Gyutae is truly a paradigm of character. I am thrilled to finally introduce Hwang Gyutae to the world via Lenscratch. While preparing this article, I was convinced that this piece would go beyond merely introducing one Korean artist, and that it would become an important document in the history of photographers around the world. Nevertheless, it is no easy feat introducing all he has achieved during his illustrious 60-year career, even with a one-to-one interview.

Hwang is one of Korea’s leading post-modernist photographers. Throughout our interview, I could see his humble and humane personality shine through his words, which is equally as brilliant as his distinct style. It became clear that his artistic genius stems from his experimental spirit, playful thinking, and unwavering willingness to confront new challenges.

He is a living history of Korean Photography.

Hwang was born in Yesan, Chungcheongnam-do in 1938. After graduating from the Department of Political Science at Dongguk University, he joined the Kyunghyang Newspaper as a photojournalist. Initially taking press photos, Hwang began his life-long career as a photographer. He was very active in the photography scene, participating in exhibitions in 1961 as a founding member of the “Modern Photography Research Society”, which he organized with the purpose of nurturing new photographers. In 1965, he came to the United States as a correspondent for the Kyunghyang Newspaper and began working for a photograph developer’s lab in Los Angeles. There he continued to develop his skills and style as an artist. The photos he took while working at the laboratory were initially an extension of his early work in Korea – at that time, the American photography industry was dominated by color, whereas the Korean photography industry was predominantly black-and-white.

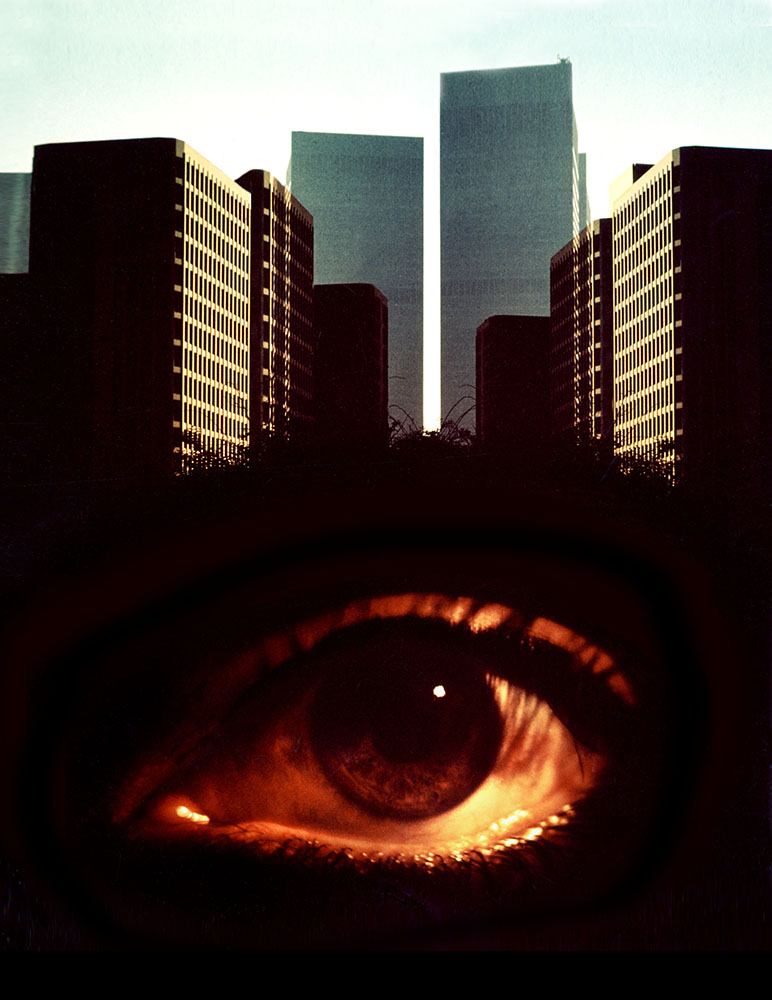

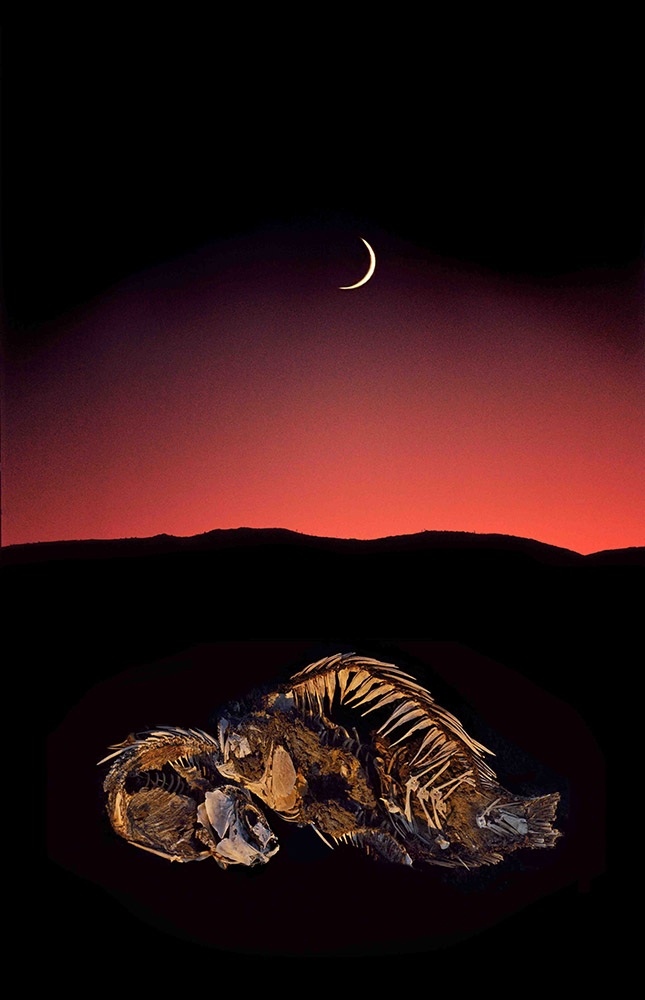

Influenced by his time working in LA, Hwang began expressing his own style of color photography in the 1970s. In a time when straight photography was predominant in both Korea and the United States, Hwang experimented with film burning, montage, double exposure, and composition via analog processes. The artist admits this experimentation was possible because he worked at a photo lab. From then on, Hwang considered photography as the subject of experimentation and entertainment to reveal his imagination.

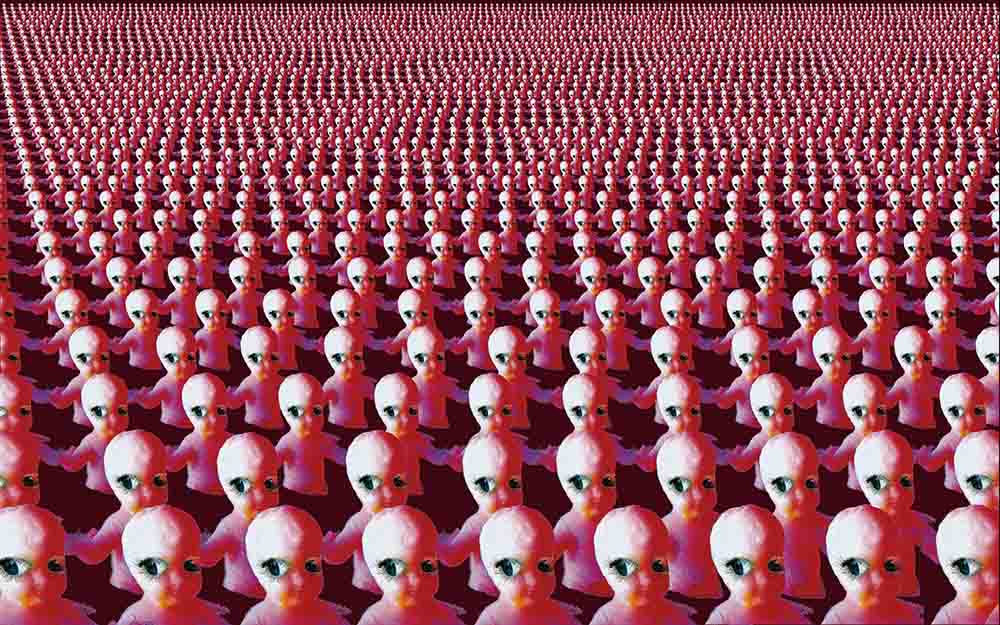

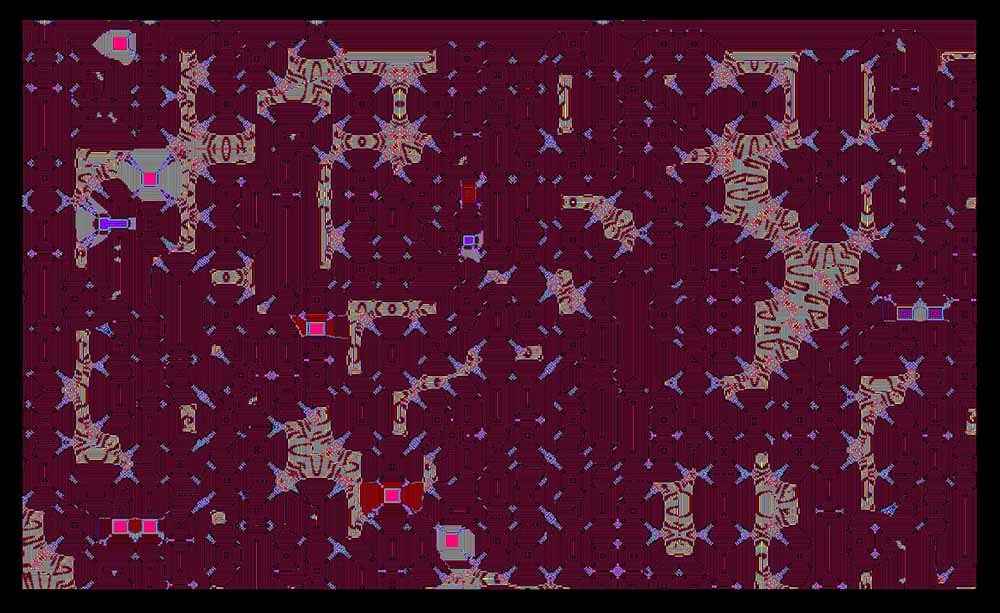

Since the advent of digital cameras in the 1980s, Hwang pioneered various techniques, such as collage and composition of digital images. During this process, he focused on the concept of the “pixel”, the smallest unit that composes a digital image. Through the Pixel series over the past 20 years, the artist has established the modern meaning of photography as a medium. Hwang claims, “Photography is no longer about mere shooting.” In his Pixel series, the initial “photography” process of taking the picture is rendered obsolete. Instead, “selection” and “enlargement” become the main focus. Hwang zooms into a particular digital image that exists on a monitor and visualizes the results that appear through visual play. In other words, he deconstructs the traditional concept of a photographic image into its most fundamental elements.

“I’m not making anything new; I’m just choosing what’s already in the pixel! In that sense, it’s like [the picture] is ready-made.” the artist declares.

True to his ever-experimental nature, Gyu-tae Hwang unveiled his 36 of his latest works at the popular 2021 Pixel’s World NFT Art Exhibition PIXEL PIXIE.

“Pixel is an uncivilized planet that is woven by the fission and fusion of bits. The planet lies somewhere among an ethereal interstellar region, far beyond our solar system. I clothe this naked planet with art, and together we dance barefoot in secret ecstasy. I’ve been living with Pixel for many years, admiring his gestures and transcendental reactions. We dance to the Spring Festival as a hundred-year tribute to Kazimir Severinovich Malevich.” –Hwang Gyutae

Hwang continues to be an inspiration to the junior photographers following the many trails he’s blazed with his endless curiosity and playful attitude he approaches his work. We are forever grateful for his extensive contributions and influence in the realm of photography to this day.

In 1961, you were a founding member of the “Modern Photography Research Society” while attending Dongguk University’s political science department. What motivated you to become interested in photography as a political science student?

The first time I joined a photography class was when I attended in Yesan Agricultural High School. I fell in love with photography, and it became a passionate hobby of mine! Ever since then, I loved taking pictures. Even after entering Dongguk University’s as a political science student, I took part in creating the university’s school newsletter. As a student reporter, I took many photos related to school articles, and then I would use my photos in the school newsletter!

Could you give some more insight about the trends and activities of the “Modern Photography Research Society” in the 1960s?

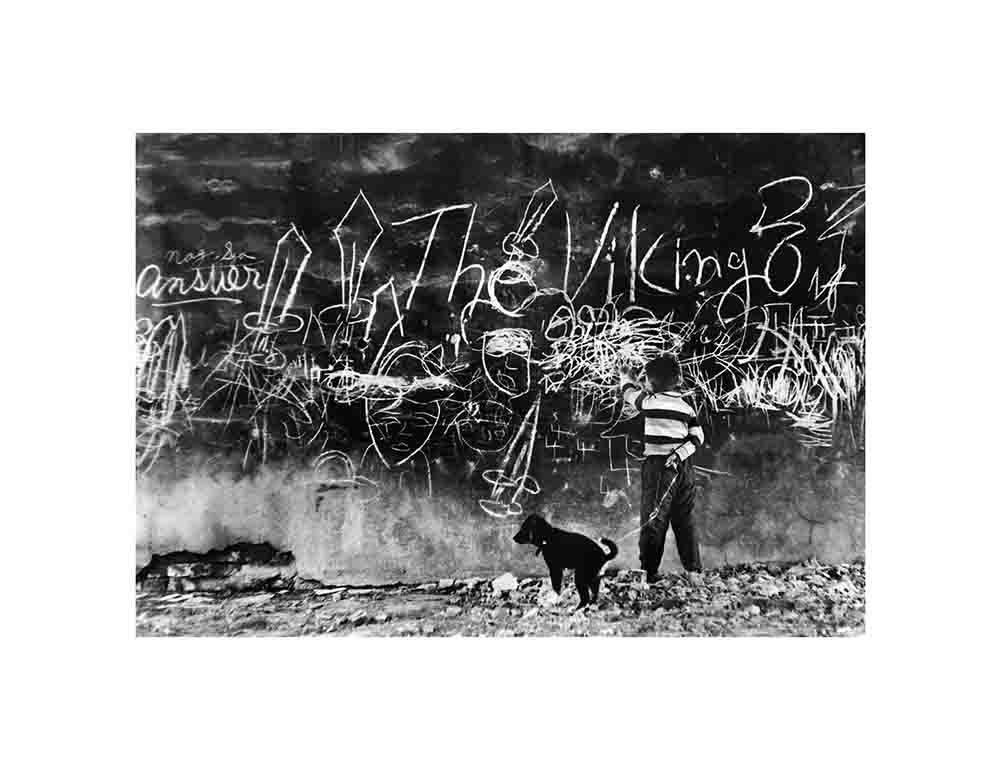

At that time, the leaders of “Salon Arus” founded the “Modern Photography Research Society” with the purpose of nurturing new and upcoming photographers. After the Korean War, the Korean photography scene was immersed in everyday realism, depicting scenes of the war and its aftermath. Fed up with this realism, other artists (including those from the “Modern Photography Research Society”) began to pay attention to work that emphasized beauty in black-and-white photography, such as formative arts and semi-abstract photography. Even so, there was still a tendency to criticize pictorialism that pursued heavily abstract themes, and to advocate the straight photography of realism.

In other words, it seemed that the “Modern Photography Research Society” floundered between accepting and opposing both realism and pictorialism trends in photography, as if the members couldn’t make up their minds. As a result, the photos from that club couldn’t completely break free from the aesthetics of realistic photography, even though the members were clearly irritated with it.

Before leaving to the United States in 1965, you submitted Road and Morning in the Forest to the Contemporary Photography Society 2nd Round in 1963. Morning in the Woods even won 4th place in the US Camera Contest held by the U.S. Camera magazine. In the 1960s, it was challenging to get information or news from other countries – there were no modern conveniences like the Internet, TV, and smartphones that we have today! How were you able to apply for a photo contest on the other side of the world?

At that time, newspapers and radio were the most common means of receiving information about anything from foreign countries. Magazines about specialized fields such as photography could only be obtained second-hand from the U.S. military base.

There were vendors selling American magazines on the street in front of the main branch of the Bank of Korea located near present-day Namdaemun. I bought these U.S. magazines like U.S. Camera and Modern Photography for viewing and Japanese magazines to study photography techniques.

Could you tell us a little more about your work “Morning in the Woods”, which won 4th place in the U.S. Camera contest?

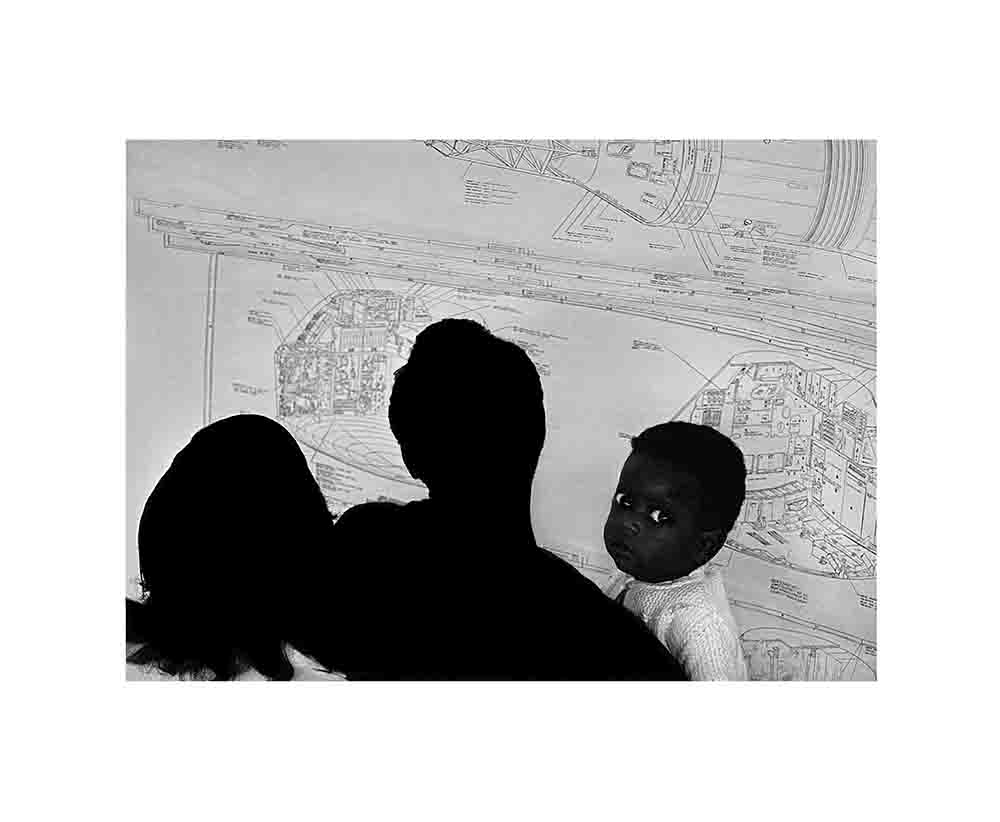

At first glance, that work doesn’t seem to differ much from other contemporary pictorial photographs. However, I created that photograph by overlapping two black-and-white film photographs printed on one sheet of photographic paper. That style of composite photography barely got any attention at the time. Since then, I’ve strived to create my photos with my own production methods that others may not understand or be interested in. For Morning in the Woods, I deliberately chose a photo of a bird flying in the sky, and another photo of a dense forest, and then combined and printed those two pictures.

Nowadays, it’s almost too easy to create a composite photograph in photoshop or other editing software. But back then, when only a single printing method from a straight shot was considered as a photograph, the attempt to create a composite photo was quite innovative.

In another interview you stated that during the 1960s, 70% of your photographs were realistic and 30% were pictorial. It appears that you took photographs of both realism and pictorialism styles in the 1960s. What do you think set your photographs apart from other artists of that time?

To be honest, at that point I didn’t concern myself with a particular “style” or “trend”. Rather, I was trying to capture everything that I saw with my eyes onto the film. If I had to really point out a “style” I had, I’d say I had similarities with the content and formality of the works of other “Modern Photography Research Society” members. However, I used modern experimental techniques when developing my pieces, such as double exposure or montage techniques, unlike my contemporaries.

As such, I explored a variety of techniques that were rejected by the photography community. Of course, as all black-and-white photographs were at the time, my works were still based on both realistic and figurative abstract photographs.

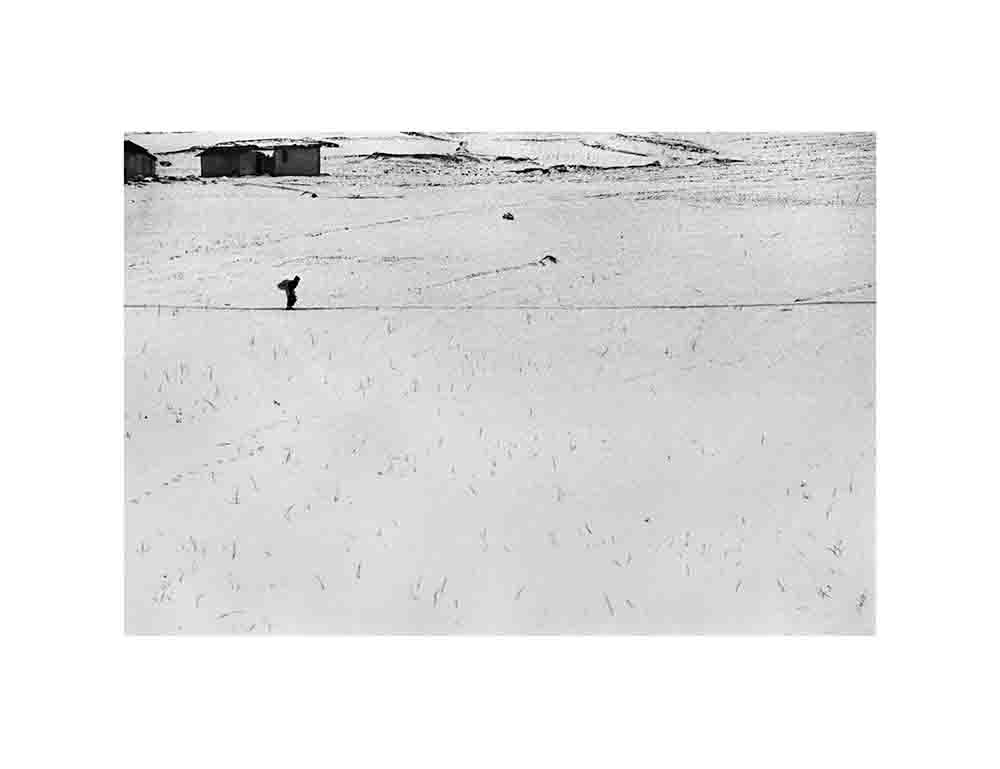

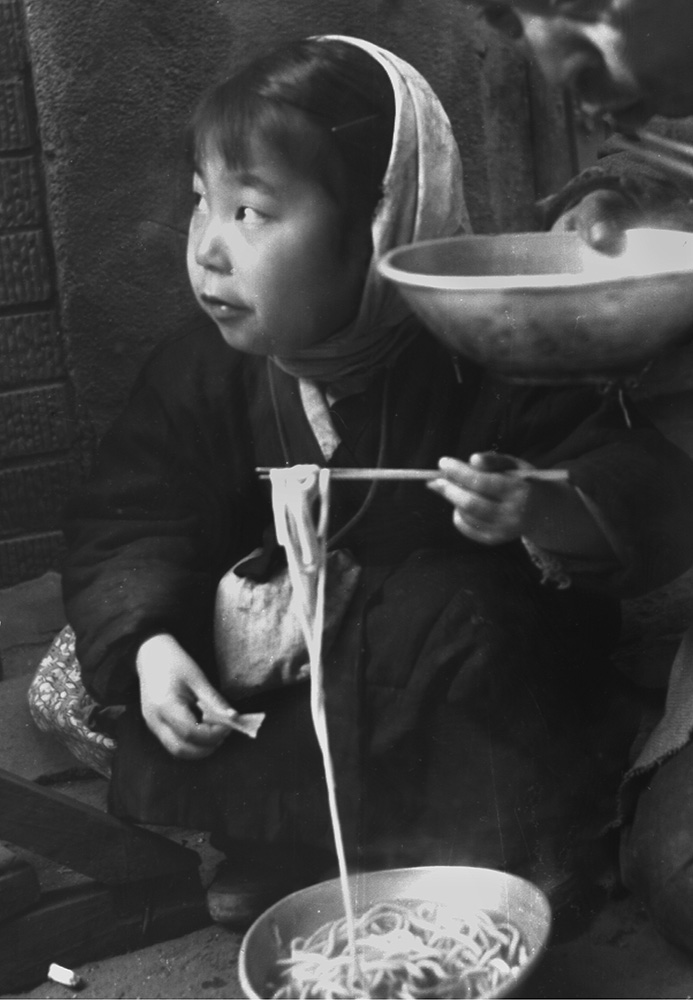

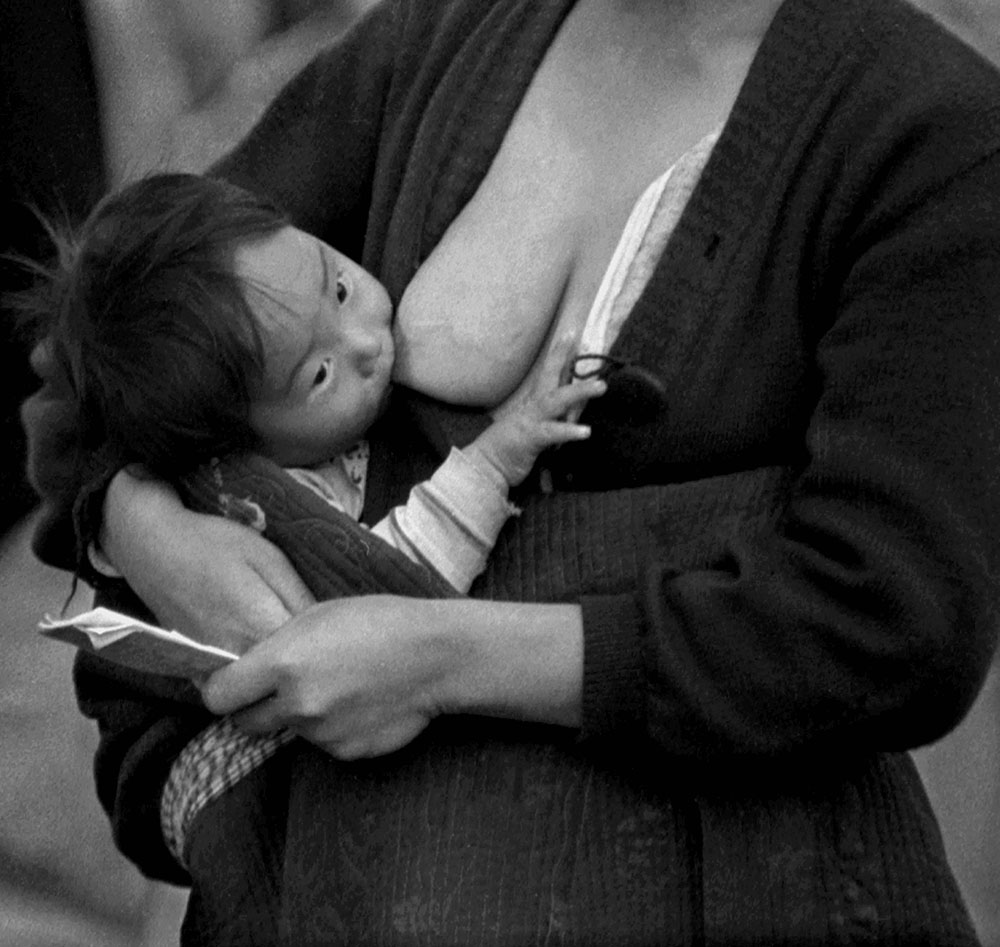

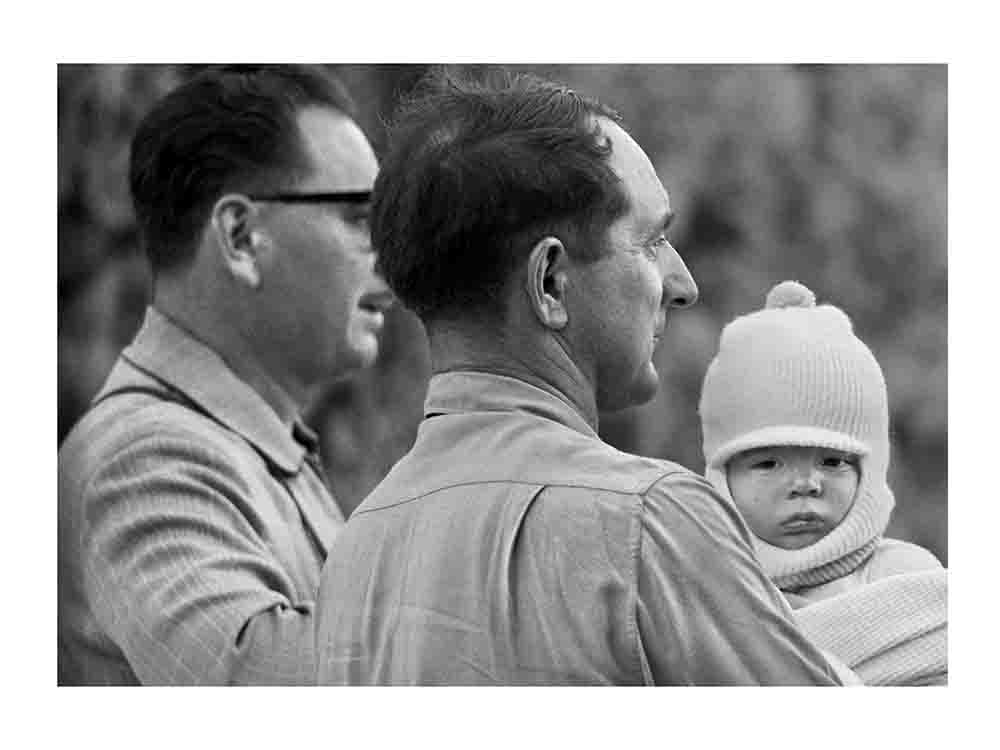

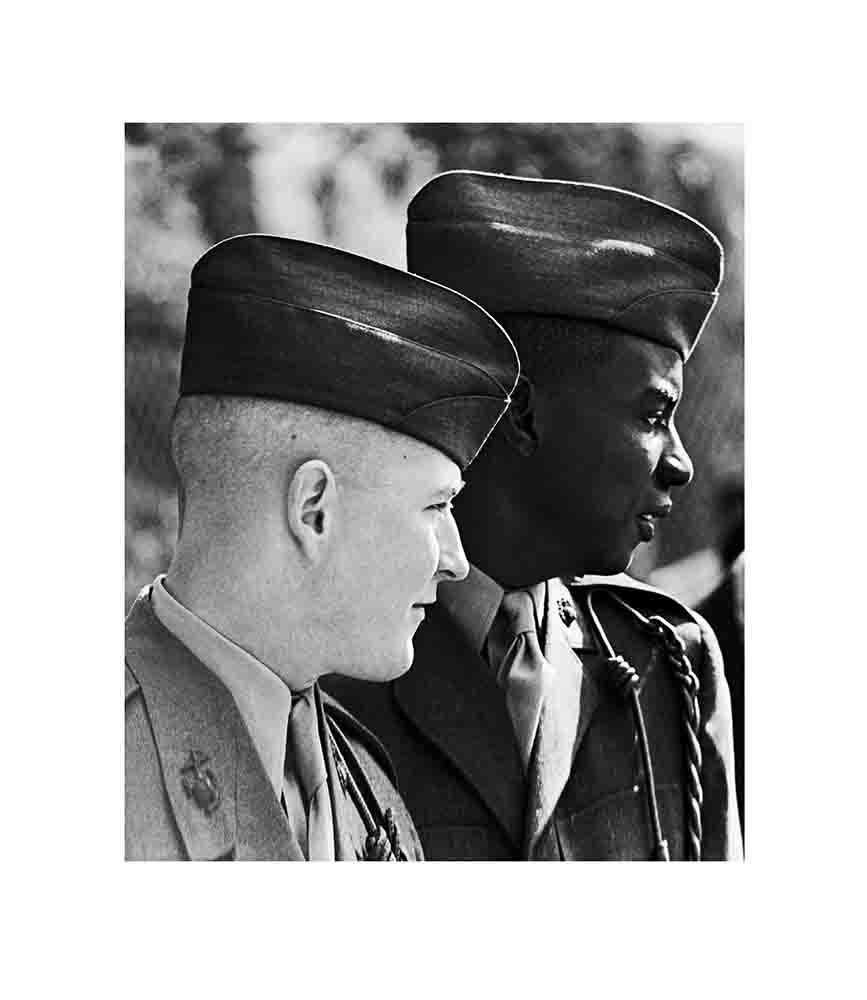

In the 1960s, the Korean and global photography industry was dominated by realistic, documentative photography – yet even in your most realistic pieces, your work was considered to have strong subjective and personal tendencies. You seem to have paid more attention to your personal feelings over the external world around you. Were you able to relate to the reality of life during that time?

Yes, to a certain extent. But it wasn’t just about adhering to either sentimentalism or realism. Of course, I did take photos that pursued the reality of the external world. However, in much of much of my realistic work, I focused on expressing my private feelings regarding a scene than the physical scene itself.

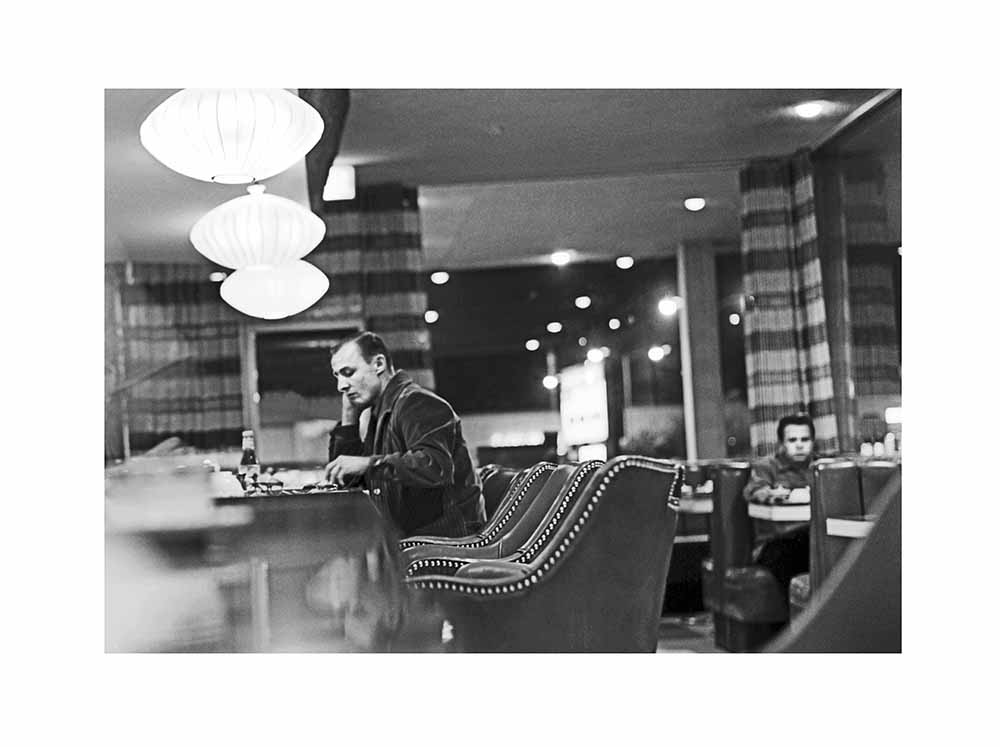

For example, if you look at the black-and-white photo Man Eating at a Restaurant taken in the United States in the 1960s, I’m not simply depicting a man eating alone, but highlighting the emotions that this scene evokes – the feeling of alienation and loneliness while living in a foreign country (in my case, the U.S.). In this photo, I point the camera inwards to myself, not outwards to the physical scene of the restaurant.

In fact, this habit of mine is also reflected in the photos of my newspaper reporter days. I used to express my subjective interpretation of the objective facts rather than recording and delivering said facts in journalism photography.

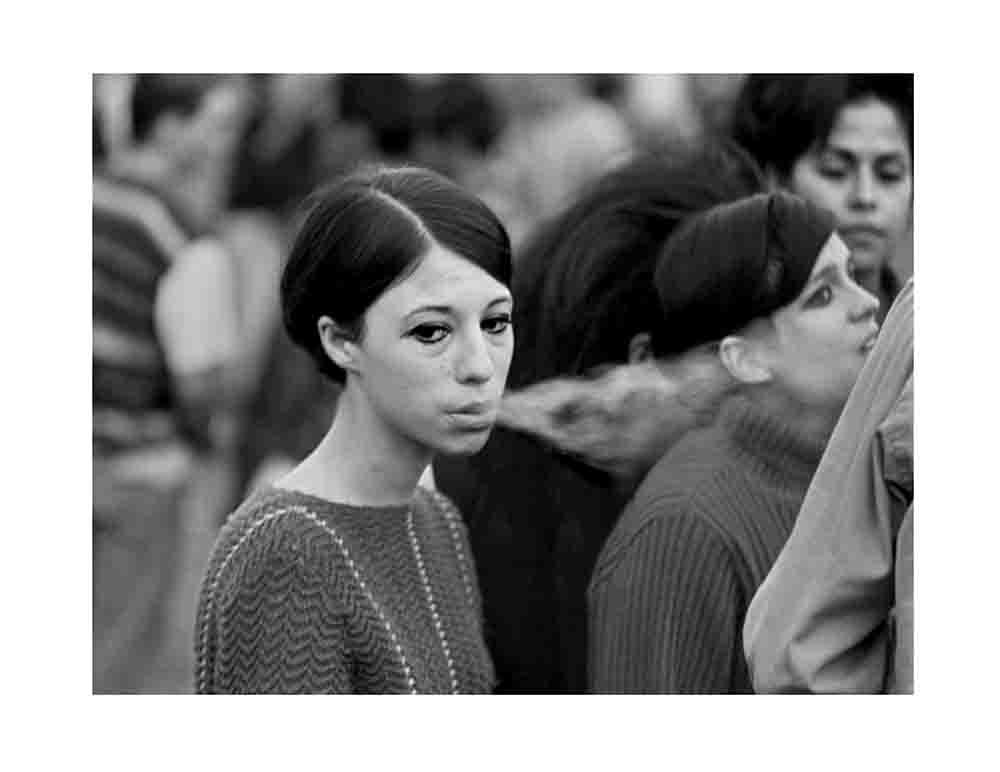

Another work, The Untitled, is a straight photograph with surreal elements. You seem to have foreseen the surreal composition the final picture would take: a mannequin-like woman seen through the door of someone’s residence next to a bizarrely placed car. These photographs are considered to be well-representative of the artist’s experimental, subjective, and surreal experimental spirit. What was the meaning of this shoot?

Rather than shooting with a meaning, I shot with the purpose of creating a sensual feeling, hence the surreal elements in an otherwise straight photograph. Although my work at the time was still tinged with amateurism, it was an important transitional period into “new photography”, and I was armed with the desire to explore the depths of this “new photography.” I think this desire enabled me to create experimental photographs in color later on.

What was the American photography community like when you went to the United States in 1965?

Life in the U.S. was very difficult in many ways. I was a fish out of water, unfamiliar with everything from the living environment to the language, to the cultural barriers. Also, unlike the Korean photography community which had only black-and-white photographs, the U.S. community was already using color photography as a means of expressing new photographic art. Moreover, U.S. artists were extensively using various experimental techniques of expression that had been rejected in Korea.

Has your experience in the U.S. changed any aspect of your photography? Which artist influenced you the most?

Of course! The biggest change was working with color photography. I was especially able to do various experiments at the color photography center in LA. Some new things I tried out were film burning, magnification, double exposure, and photo montage. Eventually, I went from taking a straight photo to creating (processing) a photo. In addition, I started to properly express my subjective inner world and delve into the world of surreality.

As for most influential artist, I have to say Jerry N. Uselsmann. When I first saw his work, I was in awe. I was fascinated that his photograph was a processed picture, not a picture that could be taken with a single shutter. This would have been impossible to do in Korea due to the lack of darkroom facilities in the 60s. I was able to play a lot of fun games such as burning, overlapping, and printing at the studio in LA, and it was even more fun because I couldn’t predict how the pictures would turn out.

After returning to Korea 1973, you opened your first color photography exhibition, showcasing 56 color experimental photographs. How did the Korean photography community react?

At that time, the Korean community largely considered my work to be absurd. I received much criticism, though I didn’t care at all. My work was well-received overseas, and I enjoyed creating what I wanted. And even in Korea, there was some positive feedback. In the Dong-A Newspaper, Myeong-dong Lee’s review stated, “It was a meaningful exhibition that showed us a different aspect of photographic art.” (1973, Myeong-dong Lee). I also heard that some people thought the subjective photographs reminded them of the bleak intolerability of reality.

Back in America, the February 1974 issue of Popular Photography magazine said, “[The photograph] is an image of private dreams in a dark room. ” They considered my work as an example of an emerging trend: A subjective photo exploring the “inner fantasy world of artist ‘Hwang Gyutae.’”

“Rather than pursuing beauty in tangible facts of daily life, I choose to embody some space or moments of inner thought into a maze of my own. This process could be a dark mirror of mine, or a teardrop hidden away, neither migrant nor tourist in a foreign land.” – Citation The 1st Hwang Gyutae Color Photo Exhibition

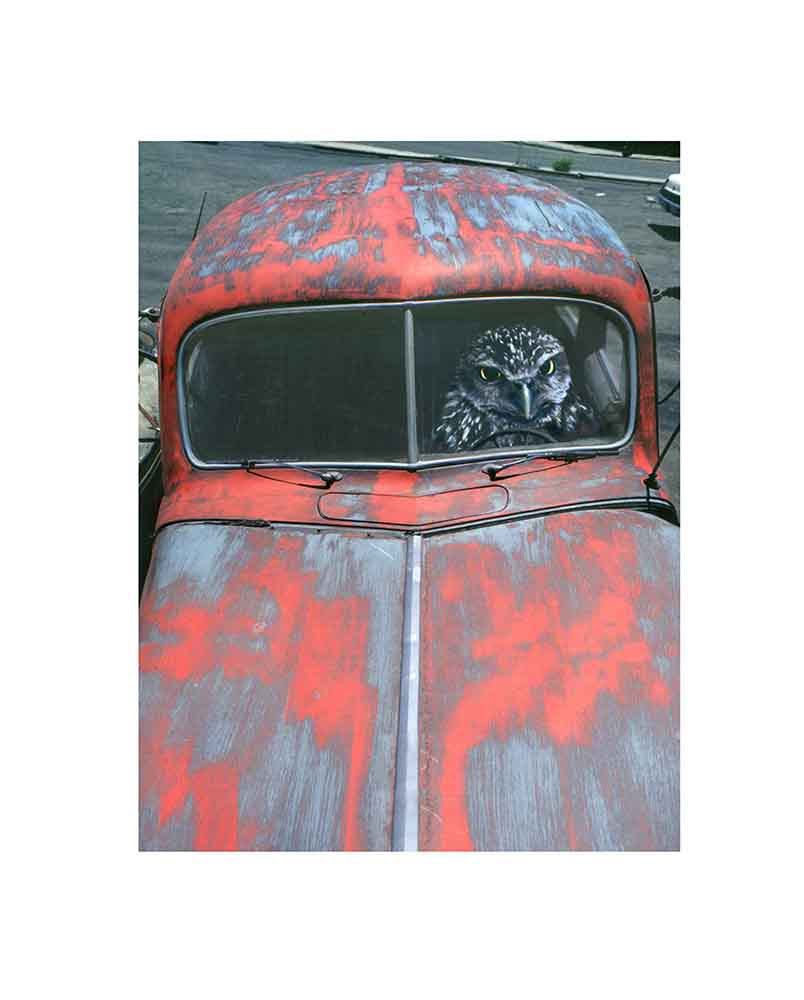

What kind of world would you like to express through your work? For example, what fantasy are you expressing in your work, Photo of an Owl in a Car published in the pages of American magazine Popular Photography (1974)?

Back in the 1960s, cars were few and sparse in Korea – so I was shocked by all the cars teeming the streets of LA. The cars speeding by me as I drove seemed liked awful monsters. I think Photo of an Owl in the Car precisely embodies the sheer terror I felt at the time. Of course, I’ve never actually seen a gigantic owl driving a car, but this picture expresses the horror I felt in a foreign land. By montaging two photos in a darkroom, I crafted a scene from my frightened imagination.

You said that you wanted to create surreal and poetic narratives through your montage technique. Could you give an example of such a work?

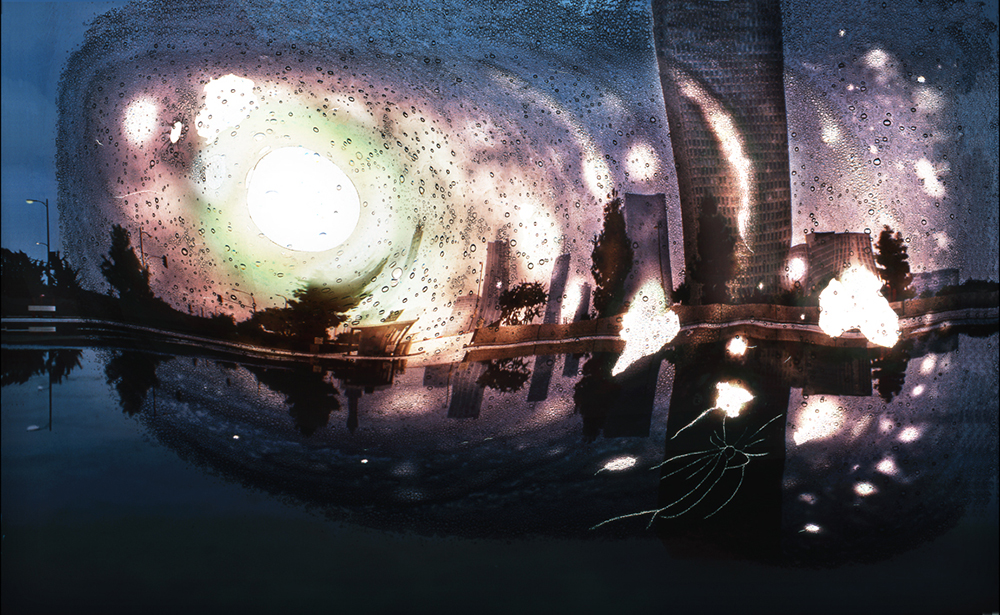

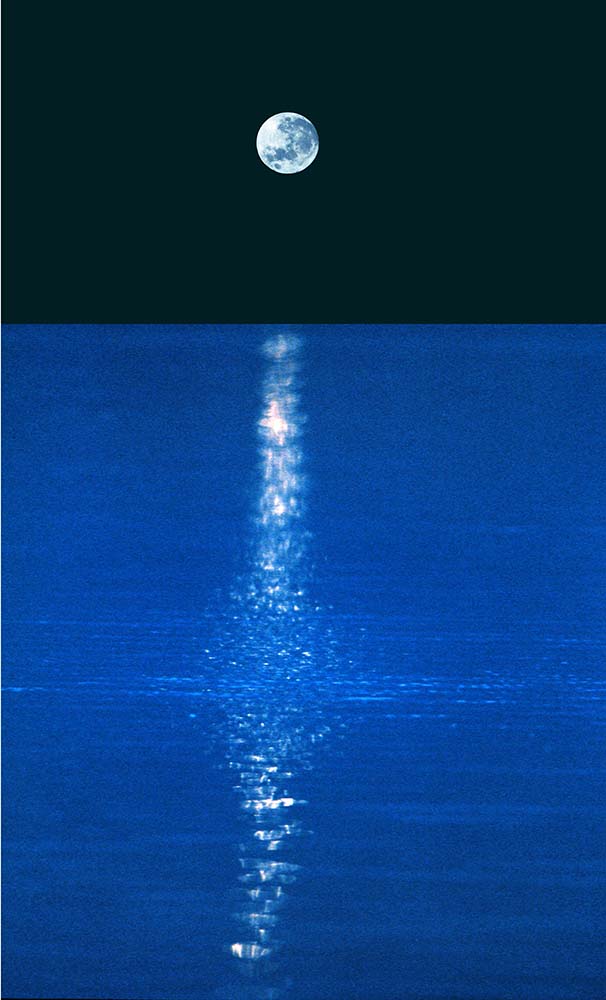

My piece Photo of the Moon in Water is a good example of this.

Once upon a time in China, there was a famous poet named Taebaek Lee. Legend has it that one night he saw the beautiful moon reflected in a crystal-clear lake. He was so entranced that he jumped into the lake to catch it and never returned.

Like the poet gazing into the moon’s reflection, I felt myself gazing into the smog, noise, and mechanics of LA – a sort of elusive beauty. I related heavily with this romantic protagonist. Thus, in Photo of the Moon in Water, I added the moon to the reflection of the building and leaves to the little pond. The photo expresses my personal inner gaze towards my life in LA with poetic effect, which realism-oriented photos could not show.

As a pioneer of avant-garde photography in Korea, you have been playing with digital images since the 1980s. Could you also give some more detail on your Pixel series?

My earlier works were inspired by the need to deal with profound concepts such as humanity, environmental degradation. However, my more recent pixel work started with a simple interest in digital images.

I consider the Pixel series to be akin to the work of Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, which focused on pure abstraction to find the fundamental elements of a painting. Using the smallest unit of a digital image – the “pixel” – I created a visual play with infinite possibilities of geometric images. My Pixel series is a multi-layered visualization of pixels – after selecting an image, I zoom into a certain section until it reveals a multitude of abstract shapes and colors.

One day, I peered into the TV screen with a loop, and there was a universe of dots and colors I’d never seen before. I was inspired to express this through pictures. So, I cropped an image and zoomed repeatedly into the pixels until I got a color and shape I liked. Finally, I chose these random pixels and cropped them. In this sense, you could consider the Pixel series as “ready-made” works – works that did not require the same technique and processing as traditional photography.

HWANG Gyutae(b.1938) ’s interest in digital images in the 1980s led to new frontiers, such as digital montage, collage, and compositing. Through an extended cycle of experimentation, he found ‘pixels’ – the base unit of images in the form of dots, in the digital images. Drawn to the infinite possibility and visual potential of these geometric images, he launched his series.

HWANG’s series lacks, or falls short of the basic process of “recording” in photography, and instead harbors “choice” and “magnification.” In other words, his works move away from the traditional process of capturing an object and making it appear on the sensitive film strip, and instead focus on discovering a wide variety of pixels in different forms and colors as they appear in the process of choosing and magnifying images and monitors. That already exists for disparate reasons, ultimately visualizing and materializing them through a range of methods. In this process, the products arising from the original image multiply. It does not matter whether these processes are shown in the photographs or not. His total directional work, which he describes as “chosen pixels rather than made products,” must be understood in the larger context of “image” studies rather than seen through the narrow lens of conventional “art” or formal history.

HWANG Gyutae was born in Choongnam, Yesan and graduated Dongguk University as a political science major, worked as a photographer for Kyunghyang Newspaper from 1984 to 1992. He became a full-time artist in the late 1950s. His first solo exhibition took place at the Seoul Press Center in 1973, and from then on, he featured his work in seventeen solo and group exhibitions at venues including Kumho Art Museum, Art Sonje Center, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul Museum of Art, Japan, and the U.S. His works are housed at a number of national and private institutions, such as the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, and Museum of Photography, Seoul.

Sunjoo Lee is a mixed media photographer based in Seoul, South Korea.

Lee’s extraordinary artistic sensibility that was once portrayed through her voice is now visible through the works portrayed through her camera lens. Her photography focuses on a unique lyrical journey into her personal life. She explores her past, present, and future world in a temporal and spatial perspective.

She received a BA in Music from Ewha Women University, a second a second BA in Photography from Chung-Ang University (Academic credit bank system), and an MFA in Plastic Art & Photography from Chung-Ang University Graduate School of Photography in Seoul, Korea. In 2019, she was awarded into the 11th cohort for the prestigious artist residency program at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary Art. Through this residency, she’s currently working on her upcoming series.

Lee’s acclaimed works have been exhibited widely throughout the years in South Korea. Most recently, she had her solo exhibition at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary art, Gwangju Korea. She’s also showcased at Gallery Now, Gallery Gong, Gallery Guha, and more in Seoul, South Korea. Her works are permanently displayed at the Haslla Arts Museum (Gangneung, Korea), and YoungWol Y. Park (Youngwol, Korea).

Her work at large, incorporates everyday objects and subjects to make visual sense of the complexities of human emotions and feelings derived from the intangible, such as music. Her photographic inspiration stems from her experiences of living and travelling abroad. She extracts the memories and various emotions born out of the human connections she’s made during that time of being in foreign spaces.

Building on this conceptual narrative, her work has landed her multiple recognitions, from the 2019 Critical Mass as a top 200 Finalist (USA) to the 1st Place Richards’ Family Trust Award during the 25th juried show at the Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, USA). In Korea, She received a growing up artist award at the Dong Gang International Photo Festival and Now and New Exhibition award at Gallery Now in Seoul Korea. Follow Sunjoo on Instagram: @sunjooleephotography

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Larissa ArazMarch 28th, 2024

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The Reluctant CaregiverFebruary 26th, 2024

-

Mexican Week: Cannon BernáldezFebruary 6th, 2024

-

Erika Kapin: Mom and MeJanuary 19th, 2024