South Korea Week: Koo Bohnchang: Silent Weapons

“After the torso slips out of what was wrapped around a body…”

Koo Bohnchang is the first photographer to be featured in this year’s South Korean artist series on Lenscratch. As a prominent figure in the South Korean photography community, he is revered by so many around the world. It was an honor to get an intimate glimpse into his world — both professional and personal.

It’s the day of our interview, and Koo was waiting for me outside his studio in Bundang (a city near Seoul) to greet me. This was a humble act that showed his character, one that is filled with respect for others.

This first impression I had of him reminded me of the Korean proverb, “One action tells ten.” The empathy and human sensitivity portrayed in many of his works came out in real life.

The moment I stepped into his studio, I briefly choked up over a whirlwind of intense, bizarre emotions. There was a picture within an unusual cold iron frame with a deep, gray-toned background. In it, existed a pair of glasses filled with haze that looked into the distance somewhere. The gaze of the glasses belonged to a nameless soldier during the Korean War. Did it belong to a Korean soldier? Or was it an American soldier? The answer: It belonged to a young soldier who gave his life during the Korean War, fighting for the country’s freedom that exists today. It’s difficult to explain in words how many breathtaking, beautiful works lined the interior of his studio’s first floor. I wanted to engage with each and every one of them, all day long. I made my way up to the second floor of his studio and passed additional artworks. One in particular caught my attention. It was an old doll hanging on the wall.

Koo explained that he bought the doll for $300 at a flea market near Rochester in the 80s. The doll was presented in its undergarments: lace stockings, Western-style inner-wear and lingerie. Seeing that Koo deliberately purchased a stripped-down doll without a fancy dress or glamorous hat for $300 in the 80’s shows a window into his unique taste and perspective. He is a collector. But not just any collector; he meticulously explores and investigates the world, creates new versions of the world he sees, and pioneers his vision through photography.

François Soulages wrote in his photography book, titled “Esthetique de la Photographie”: “Art materializes its purpose from a trivial place and draws caution towards the far-distant space created toward the insignificant. Art then fixates on this.”

Looking at Koo’s beautiful series, I believe he is opening up a whole new world from his exploration into the trivial. For instance, old glasses, which are an “object of reality,” allow photography to reveal the unattainable traces of the human being who was wearing it.

“Photography does not restore the object-realite and the object-essence of reality. Photography faces an object-probleme, an object-pretexte as a pretext.”- By François Soulages, “Esthetique de la Photographie”

Koo Bohnchang attended Yonsei University majoring in Business Administration and later studied photography in Hamburg, Germany. He was a professor at Kyungil University and a visiting professor in London Saint Martin School.

Koo’s work has always dealt with the passage of time. He captures still and fragile moments, attempting to reveal the unseen breath of life. Since 2004, Koo has photographed traditional Korean white porcelain ceramics, in his Vessel series which highlights the simplistic beauty of Korea’s cultural heritage. To create the Vessel series, Koo photographed plain white porcelains in the collections of museums in Korea and abroad. For him, these wares echo the essence of the Joseon aesthetic, and because they are often stained, cracked, and worn by everyday use-they are a perfect subject through which to convey warm traces of human life.

His works have been exhibited in over 40 solo exhibitions including Samsung Rodin Gallery, Seoul (2001), Peabody Essex Museum, Massachusetts (2002), Camera Obscura, Paris (2004), Kukje Gallery, Seoul and Kahitsukan Kyoto Museum of Contemporary Art (2006), Goeun Museum of Photography, Busan (2007), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia (2010) and many.

His collections are at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Museum of Fine art, Houston, Kahitsukan Kyoto Museum of Contemporary Art, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea, Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Musée Guimet, Paris and publications are Deep Breath in Silence、Revealed Personas、Vessels for the Heart、How to Capture the Touching Moment in Korea and Hysteric Nine、Vessel、Everyday Treasures in Japan. Follow KooBohnchang on Instagram: @koobohnchang

Silent Weapons

War causes damage to not only cities and nature, but also on the hearts and minds of people.

I keep thinking of the 101-year-old mother, who still believes that her son is not dead and calls her son’s name in a trembling voice–it makes us think about the motherhood that evokes humanity’s most fundamental longing.

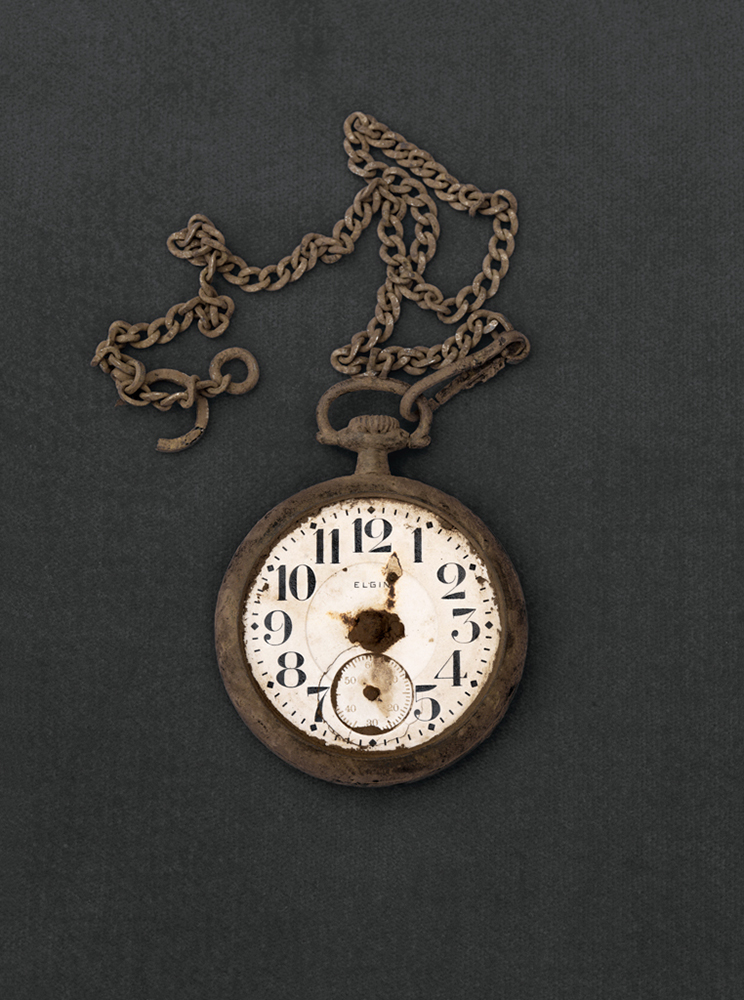

While photographing the items used during the Korean War in the War Memorial of Korea, I tried to reflect on the horrors and tragedy of war through the weapons that were kept silent in the gray background. I prayed for peace and reunification of this land through weapons that kept silent.

The Korean War, the confrontation between South and North Korea, is still ongoing.

– From Koo Bohnchang’s notes

Please tell us about your Silent Weapons series that is being featured in Lenscratch.

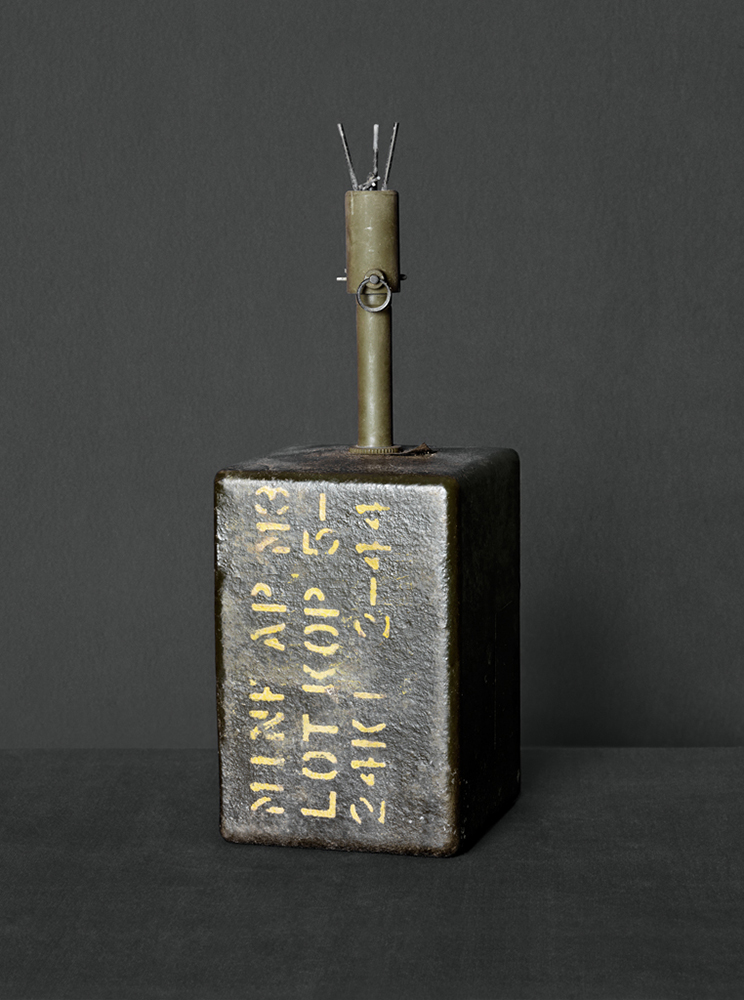

The Korean War began with North Korea’s invasion of South Korea in 1950. The reality is that Korea is still in a state of ceasefire, not true peace. After the ‘Korean Armistice Agreement’ made in 1953, a Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) of 2 kilometers wide from north to south was established. Today, the DMZ has become a symbol of Korea. Silent Weapons is a photo book titled DMZ, which contains photos of war relics found in the exhibition hall and storage of the War Memorial of Korea. Those objects include remnants of warfare such as bullets, grenades, knives, as well as other items used by soldiers in the war. Using boots, helmets, glasses, belts, plates, and spoons, I document the traces of the soldiers who left them behind.

All of Koreans remember the pain of the Korean War and are living in an unforgettable reality as a divided country. You seem to be especially interested in war and express it through your work. Do you have any personal reasons for this?

Personally, my parents are from Gaeseong, North Korea. When they fled to the south during the Korean War, my paternal grandfather was left behind in the north. To this day, many families have not yet resolved the pain of being separated by war, and their stories are becoming part of history. I try to express the grim and morbid nature of war in aesthetic visual terms, while also embodying the invisible stench and traces of the soldiers’ wounds.

Among the many war relics of Silent Weapons, were there any objects that made you feel special or intense?

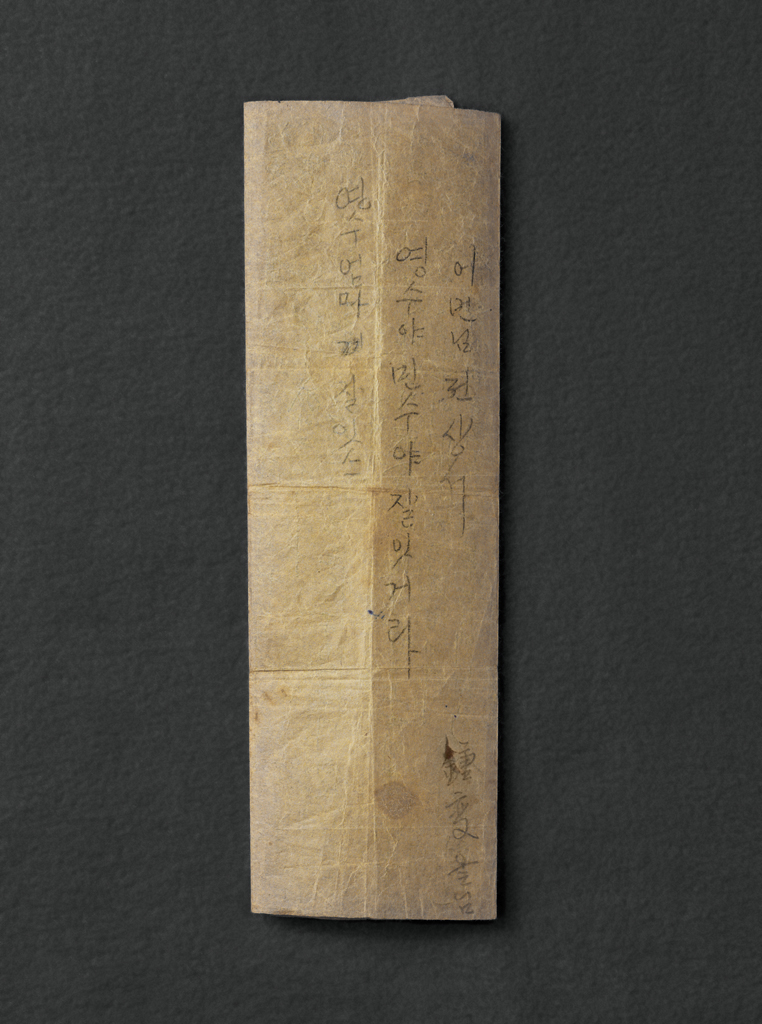

Yes, I felt the pain of war intensely from the old-fashioned knife and the bent spoon. In these objects, I could feel an intangible sense of horror. Another object, a young soldier’s belt, is a powerful remnant of war. As François Soulages said, “The belt is a sign that the body has escaped from what was wrapped around it.” In addition, there is a letter I found while looking for objects to be photographed at the War Memorial of Korea for this series. Entitled “My death letter to my mother” on the front, this letter broke my heart. It was found in the arms of a dead soldier. The faded stationary spoke to me of the unspeakable cruelty and pain of war.

Then, after the mother, the grenade, and finally the belt is the only one to cry.

After graduating from Yonsei University in Seoul Korea, which back in the 70s was said to guarantee a prestigious future for all graduates, you went to the National University of Art and Design in Hamburg to study photography.

What motivated you to take on this big adventure?

Since childhood, I have had a strong creative drive. Unfortunately, I thought my college studies had to be grounded in reality so I majored in business administration, which was believed to guarantee you a successful career and stable future. However, I could not give up my childhood dream of becoming an artist, and my passion for creation exploded. In the end, I chose my dreams and majored in photography design at the National University of Art and Design in Hamburg, Germany in 1985.

Please tell us briefly about the Hamburg State University of Art and Design. How was your photography influenced by your education at the German Academy of Fine Arts?

In Korean universities, art or photography majors are determined from the admission process, but in Germany, students enter the College of Art and Design without choosing their areas of focus. In addition, admissions are based on the artistic potential and passion of each student. During the first two years, students explore various subjects such as typography, printmaking, graphic design, poster production, and so on. Based on those experiences, students then choose an art genre that best expresses their strengths and dreams.

Though originally, I had wanted to be a painter, the professor of the photography department praised me for taking good pictures, and I discovered that I had a talent for photography. I became more focused on photography as I was charmed by the quick results and joy of capturing something with the camera and making it mine.

My education in Germany has undoubtedly had a great influence on my work to this day. German art education emphasizes the ability to observe something with great detail. It also taught me how to express a story without frills. Moreover, thanks to my education in design and graphic production during the first two exploratory years, I was able to return to Korea as an artist capable of working across all genres such as theatre, film, and fashion. My exposure to so many different art forms and aesthetics trained my eye and set high standards for my artistic tastes. I felt happy creating art with this unique background, and that became the driving force for good works. Along with the pursuit of restraint and simplicity through 6 years of German art education, I think my emotions as a Korean are finally being expressed through my work.

What is the driving force behind your endless ideas and passion as an active artist after working for 40 years from 1985?

I think the driving forces as an artist are the desire to learn and to express something. Like Leonardo da Vinci, I believe curiosity is essential for an artist. I am interested in many fields I am not familiar with, and I have the habit of collecting articles from newspapers and magazines–I am constantly researching. Such curiosity comes from my ability to observe. Whenever I start a new work, I get help from the resources I’ve gathered before.

Most importantly, however, the driving forces that allow me to continue working are the joy I feel from shooting a photograph, and the sense of accomplishment that I feel when I create something solely special to me.

What advice would you give to aspiring artists to create good work?

If you observe every day, mundane things with attention and affection, these mundane things become special. For example, when you feel a connection with a certain object, landscape, or person’s face, you can see a new world if you open your mind and observe. I think that is inspiration to create good work for yourself.

Do you have a way to create your own photos?

I think any artist feels satisfied when they create a work no one else has created before. In other words, you have to find your own way of expression, and to do that, you do a lot of research first. By studying the work of existing artists, you look for as many images as possible and find inspiration. In this way, I find, and express things others have not expressed through my own style and experiences. Also, I think a lot. I especially think a lot before taking a picture.

Although many of your works differ from each other, I feel that they all have some common ground. Do you have any personal intentions that you’ve been expressing all along?

My work is seen as a variety of works in terms of expression methods and subjects. But through these works, I am always trying to convey messages about traces of time, scars, memories, and temporality. I am also very interested in the sublime, and the goal of my work is to show the sublime through my work. (In other words, revealing the invisible.) In my work, I aim to show the invisible traces of human energy or breath hidden behind inanimate objects such as white porcelain, masks, armor, and soap. This is expressed as a visual story.

Nowadays, with the popularization of cameras and development of smartphones, it seems that everyone is a photographer. What advice would you give to artists in order to become a serious photographer?

In today’s world, anyone can easily create an image. That’s why it’s easy to throw around the term “photographer” or “artist”. A serious photographer must be conscious of the story they want to show through their life, constantly asking questions and working hard to reveal that story through compelling visual language.

What would you like to say to your juniors and young photographers?

I hope you can be curious about the world and ponder deeply upon what kind of story you want to tell. Photography requires unwavering patience and awareness of the story you want to tell. In other words, you must be centered and focus on your work. In addition, you should be in touch with current events, and consider whether your chosen theme can objectively relate to others living in the same time period.

Lastly, what is the artist’s latest work topic and future plans?

As I said before, I am curious about and interested in all fields, especially those I do not know. That’s why I still have a lot of work and ideas I want to execute. I am in the process of bringing out completed, unpublished works and organizing them. Among them, I am particularly interested in the projects depicting motherhood, such as: war and mothers, dead sons, daughters and mothers, and mothers who have lost their children in the military around the world. The existence of the mother is the fundamental longing of mankind, and I plan to do work that contains the sorrows of such mothers in the future.

“First, the name of the photograph: Park Wea-Yeon. Then, her age: 101 years; Park Wea-Yeon has reached and surpassed the symbolic 100 years; a fear takes the viewer of the image which sees the image of the almost impossible, much stronger than an image of the origin of the world which is already there; an image of the future of the world, a future without illusion, an image of the world which might never be there; image of the unthinkable, visible of the unthinkable: strength of photography, even if the “it has been played” can still creep into the image. Finally, her relationship to the war: this woman is a mother, and she lost her son during the Korean War; so, she got lost somewhere, faced with this irremediable loss; infinite loss, infinite pain, but also infinite memory of the son, of death and of war, remains infinite like the nature of photography. Mother, love, death. As with Roland Barthes, but this time, on the mother’s side and not on the son’s side. Like the Pieta, Mary with the dead Jesus in her arms; Does Mary know that Jesus is the Christ and that he will be resurrected? have we ever told her?

Thus, with this work, Koo articulates the fate of political memories and the very nature of photography. Photography is indeed this astonishing articulation of the irreversible and the unfinished. It is an articulation on the one hand of the irreversible obtaining of the generalized digital matrix – by this productive confrontation of a photographing subject with something to be photographed, thanks to the mediation of photographic material and photographic action – and of another part of the unfinished work of the digital matrix – from the same initial matrix, an infinite number of totally different photos can be obtained by intervening in a particular way during the six operations producing the photograph. It resembles the process of creating memory, which is anything but digital memory.

However, photography with Koo is also the articulation of loss and the rest.

Loss of the unique circumstances which are the causes of the photographic act, of the moment of this act, of the political memory to be photographed and of the generalized attainment of the irreversible digital matrix, in short of time and of the past. Remains made up of these photos that can be taken from the matrix. The loss is irremediable: the photograph shouts it to us, shows it to us, makes us imagine it; if the loss is absolute and violent, it is not so much because time, political memory or the lost being was previously of great value to us in itself – albeit a son, yes, a son, the flesh of the mother…. It is because they are lost that suddenly, their value becomes absolute and immediately, these absolute reaches and contaminates the loss, our loss; irreplaceability of the son, except for the Risen One, and again … And all those sons of a country, of a cause or of an illusion who died for their homeland … The rest cannot be a miracle cure, except for those who need to believe in miracles; in fact, does it relieve us of the loss, does it allow us to mourn it? Sometimes, maybe; in any case, it is the only thing that remains to us, what we will have to fight with, to struggle with, to fight against – but it will not be war -, thanks to which the artist will be able to work: photography or the art of accommodating leftovers … Infinite losses, infinite remains …

Then, after the mother, the grenade, and finally the belt is the only one to cry.

Terrible is that image of the grenade: it’s just that, but it’s all an image of an announced death. It is a sad annunciation, without an angel or a mother. It is a reality that is to come irremediably. It is a magisterial mise en scène of the object of death, given its radical simplicity, without mannerism: “He is going to die. He is dead. “

And the belt is there, the real being of the dead. As if it surrounded the body, but without the body. Presence of absence? Presence of the absent? The viewer can only suffocate in front of this sublime here below.”

Thus, the work of the Korean Koo gives us a glimpse that with creation the memory is to come. And that to glimpse it is neither to see it, nor to know it, but something on the sublimated side of that-seeing. Both the identity of the time and the work to come are at stake. So is art – its metamorphosis of memory.

The aesthetics of photography would be necessary: to think it better; to better make it sensitive; to better understand why it is art and enriches art.

-From Francois Soulages, From non-art, the photography /3/Aesthetics of Korean photography: an example, Koo Bohnchang

Sunjoo Lee is a mixed media photographer based in Seoul, South Korea.

Lee’s extraordinary artistic sensibility that was once portrayed through her voice is now visible through the works portrayed through her camera lens. Her photography focuses on a unique lyrical journey into her personal life. She explores her past, present, and future world in a temporal and spatial perspective.

She received a BA in Music from Ewha Women University, a second BA in Photography from Chung-Ang University, and an MFA in Plastic Art & Photography from Chung-Ang University Graduate School of Photography in Seoul, Korea. In 2019, she was awarded into the 11th cohort for the prestigious artist residency program at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary Art. Through this residency, she’s currently working on her upcoming series.

Lee’s acclaimed works have been exhibited widely throughout the years in South Korea. Most recently, she had her solo exhibition at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary art, Gwangju Korea. She’s also showcased at Gallery Now, Gallery Gong, Gallery Guha, and more in Seoul, South Korea. Her works are permanently displayed at the Haslla Arts Museum (Gangneung, Korea), and YoungWol Y. Park (Youngwol, Korea).

Her work at large, incorporates everyday objects and subjects to make visual sense of the complexities of human emotions and feelings derived from the intangible, such as music. Her photographic inspiration stems from her experiences of living and travelling abroad. She extracts the memories and various emotions born out of the human connections she’s made during that time of being in foreign spaces.

Building on this conceptual narrative, her work has landed her multiple recognitions, from the 2019 Critical Mass as a top 200 Finalist (USA) to the 1st Place Richards’ Family Trust Award during the 25th juried show at the Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, USA). In Korea, She received a growing up artist award at the Dong Gang International Photo Festival and Now and New Exhibition award at Gallery Now in Seoul Korea. Follow Sunjoo on Instagram: @sunjooleephotography

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026

-

Sunjoo Lee: Untold

October 20th, 2025 -

Suzanne Theodora White in Conversation with Frazier KingSeptember 10th, 2025

-

2025 PPA Photo Award Winner: Teela Misa DeLeónSeptember 5th, 2025