Alí Marín: En La Tierra Baja

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series En La Tierra Baja by Alí Marín.

Born in the state of Veracruz in Mexico, and beginning as a photojournalist in 2012, Alí Marín is now a visual storyteller transiting across the center and south of Mexico. In his documentary photography uses family albums, archives, direct photography, video and sound, to explore topics related to memory, identity, geography and travel. Marín was a finalist in the 2021 award for new environmental narratives Photo Festival Lagacilly and Fisheye Magazine. Selected within the visual artists catalog of the Center of The Image Mexico 2021, Nominated 6×6 Talent World Press Photo North and Central America 2020, Marín was awarded the Young Creators grant supported by the National Fund for Culture and Arts (FONCA). Alí’s work has been exhibited and published individually and collectively across Mexico, Latin America and Spain.

Alí received a Master’s Degree in Travel Journalism from the Universitat Autònoma of Barcelona (UAB). The Creative Documental and Contemporary Photography Seminar in FUGA Barcelona Spain, and holds a Journalism Degree at University UV of Mexico. He participated in Camp 20 Photographers Mexico in Tlacotalpan, Veracruz. Alí is founder and co-producer of the International Festival of Photojournalism and Documentary Photography, MIRAR DISTINTO in Mexico. And a member of latin collective TRASLUZ.

En La Tierra Baja

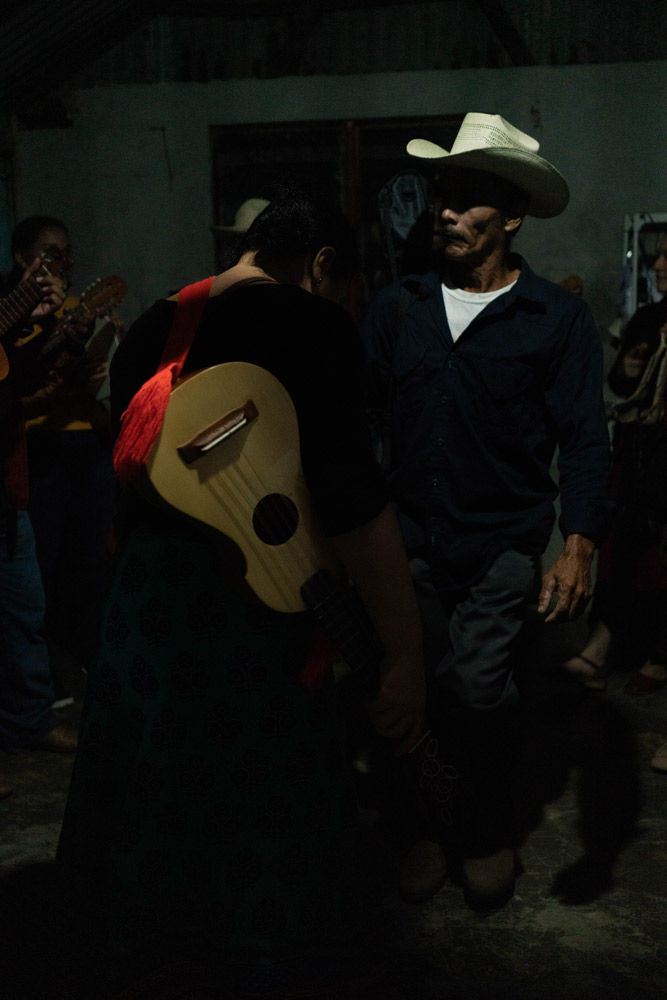

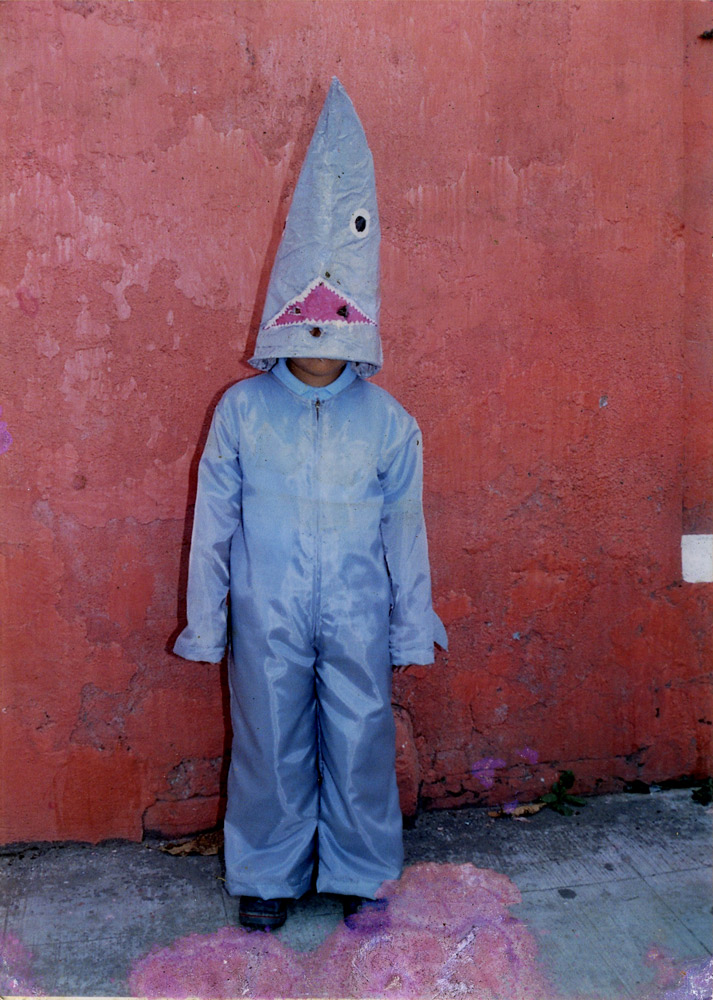

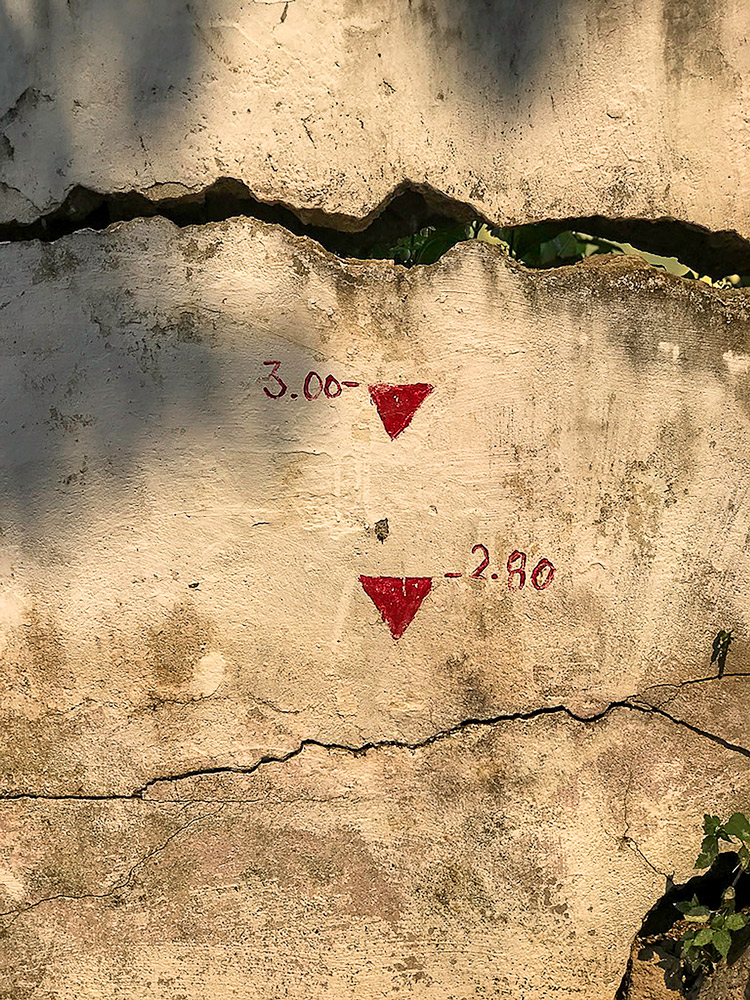

At the river basin of the Papaloapan river in Veracruz, Mexico, the people have built a story, an economy and a very peculiar culture and identity. Their lives are both determined and threatened by the river’s annual swelling. Nevertheless, their roots withstand nature and resist forgetting.

En la Tierra Baja is a photographic narrative that starts from the search for a little family album in order to explore the relationship between the community of Tlacotalpan and the river, not only as a way of living but also as a form of resistance. The yearly rise of the river poses a historical contradiction: on one hand, it is a means of transport, an economic source, a reason to belong and an originator of traditions; but on the other, it is an unstoppable force of nature that threatens to kill everything. However, there’s no river capable of erasing the intangible, the permanent.

This is a story about the conservation and preservation of a memory. A story about the inherent necessity to belong to our environment. This is the story of a town whose existence is essential in the understanding of life in this region—a town that refuses to vanish and that prevails by telling itself: “the river gives but it also takes.”

Daniel George: Besides being a native of Veracruz, what drew you to photograph the Papaloapan River, and more specifically, the Tlacotalpan community?

Alí Marín: The attraction begins with the stories about my maternal grandmother “Lola” and her hometown of Tlacotalpan, where my mother was born and raised until she was seventeen years old. My grandmother died a few days before my mother’s seventeenth birthday, so I did not meet her, that is why my mother told me how she was and how her childhood was, what the river was like in those days, my great-grandfather was a ship captain In the early years of 1900s, he introduced ships from the Gulf of Mexico to the Papaloapan River specifically at the Tlacotalpan dock. When I asked my mother what “lola” my grandmother was like, she told me that there was only one family photo where she appeared and that she would find a way to obtain it. Finally the photo arrived, and for a moment the curiosity ceased, however, some time later, the talks with my great-uncle, my grandmother’s brother, triggered a deep need to know more about her, her land … Tlacotalpan and its river the Papaloapan. The stories of my mother, the memory of my grandmother, and the stories about the river, were the engine that led me to start this journey, instead of my roots.

DG: Tell us more about your interest in framing this work through the narrative of your family album. Why do you feel it is important that you interweave this personal story?

AM: First of all because it was born from there, that is, from the shortages of a family album within my family. That need to put a face on my grandmother was transcendental in this search for existential meaning. The family album is the channel that links me to my past, it helps me to dialogue with it, it confronts me, and it also helps me understand my identity and that of the territory I inhabit. At certain times it is a therapy, it helps me heal, to rediscover myself and not lose my way. The personal is the anchor of this story and from there I unfold the experiences that I myself live in Tlacotalpan and the Papaloapan River, they upset me, they matter to me and above all I feel them. I believe that we all share conditions that make us human beings, pain, joy, sadness, fear of loss and love for our land are genuine human experiences that connect us. Identify, feel and understand them and then share them, and boom! Suddenly you realize that many people have experienced or experience the same as you, it seems to me that this is where the personal makes sense, when it becomes collective.

DG: You write, “This is the story of a town whose existence is essential in the understanding of life in this region.” In what ways do your photographs communicate the broader history of the area?

AM: Tlacotalpan was historically a point of communion within the lower basin of the Papaloapan River, the second largest hydrological basin in Mexico. Its first inhabitants were indigenous Totonacas who came to the water banks in search of fish. The conquest and expansion of the Spaniards, in this case Andalusians, makes them also feel attracted to this territory, to later bring slaves from black Africa, who will cultivate sugar cane, among many other tasks. The above, together with the geography of the place, has built a very peculiar framework. Tlacotalpan is the hot spot where identities merge, building and feeding on each other to form the same. Some historians call it the triple root: Indigenous, Andalusian and Black Africa. Through my photographs I try to dialogue about the relationship of the human being with geography, and how this link generates identity, ways of resisting and ways of living. For example, many families do not have photographs of their grandparents, ancestors or even of themselves because the Papaloapan River carries them away every time it overflows and floods the town. Tlacotalpan and its communities is always the most affected place, however, it is also the starting point of identity in this region of Mexico and pride of the area. Tlacotalpan is known as the Pearl of the Papalopan. Understanding life in this region is understanding an important part of the identity of Veracruz, one of the gateway to Mexico and Latin America.

DG: The contradiction that the river creates the potential of both supplying bounty and destruction is an intriguing theme of the project. Would you expand on this topic and share further insights into this situation?

AM: Yes! That’s right, on one occasion one of my grandmother’s best friends told me “the river gives, but it also takes away.” Historically, the river was the trigger for everything, the amount of fish and the geography were the key to the economic development of the area. At the beginning of the 20th century, the only way to reach almost all the towns in the Papalopan basin was through the river and Tlacotalpan was the only port, so to speak, in the area. The Rio Papaloapan was also a river highway, commerce circulated there. That generated great expectations among the community and little by little people came to live there. With the arrival of the train, the river lost its strength as a means of transport, the merchandise now circulated by another means. However, there were still fish, cattle and sugar cane. With the pollution of the rivers and the climate change, living here became an act of resistance “only the brave stay, says my uncle Mariano.” Although there has always been a historical dichotomy, the balance is tilting more and more towards the overflowing of the river due to the increasingly unpredictable heavy rains. This generates a battle for the conservation of memory, tangible and intangible heritage, ancestral knowledge, and everything that reminds us and makes us who we are. It’s funny, everything started by the river and now, although silently but constantly, everything is at risk by the river. That is why it makes so much sense to me what Chepi said “the river gives, but it also takes away.”

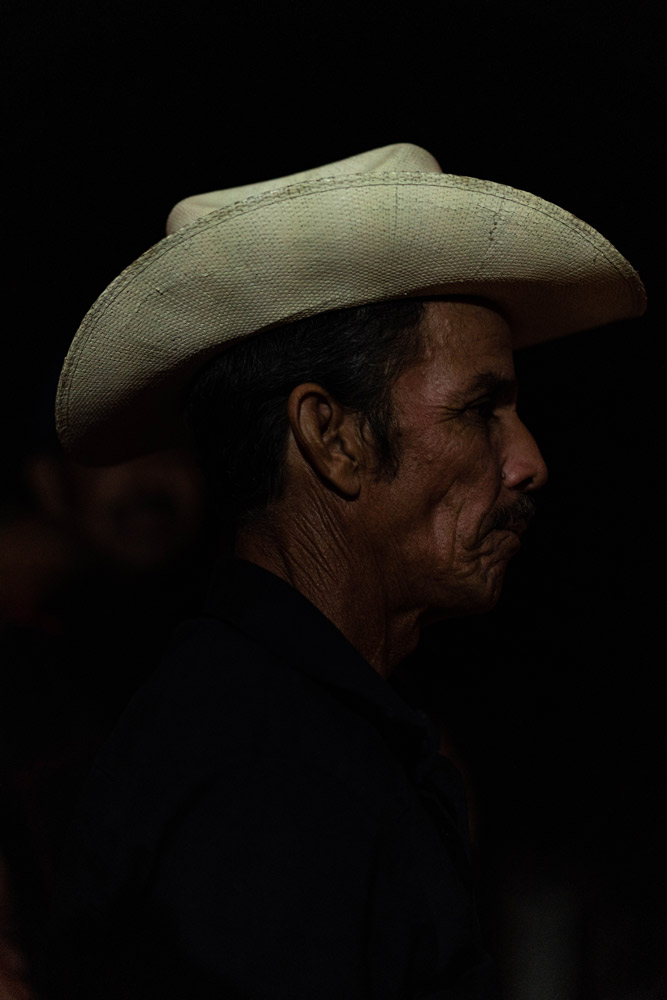

DG: I was drawn to your photographs, specifically to your portraits, because of the way you ennoble your subjects. As a journalist, could you talk to us about your approach and methods to storytelling?

AM: Thank you, I really appreciate it! You know I always start from the personal, I immerse myself a lot in my emotions, that is, what does this story generate for me? How does it go through me? What atmosphere is building? How am i feeling What does this experience generate for me? I try to answer these questions with family albums, archives, photographs and lately with videos and sound, but a lot has happened internally before. Regarding the portraits, I try to reflect the emotional identity that exists at that moment, how the person feels with everything that surrounds him, I try in some way to discover how he wants to be represented, of course in the end it is one who decides, but at least Putting it in my mind makes me question myself. I think that when I am photographing I am full of questions, some are easier to answer, others not so much. I like to think that this is how my photographs are.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Gadisse Lee: Self-PortraitsDecember 16th, 2025

-

Scott Offen: GraceDecember 12th, 2025

-

Izabella Demavlys: Without A Face | Richards Family PrizeDecember 11th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 2November 27th, 2025