The Dynamics of Photography and Disability: Kevin Quiles Bonilla

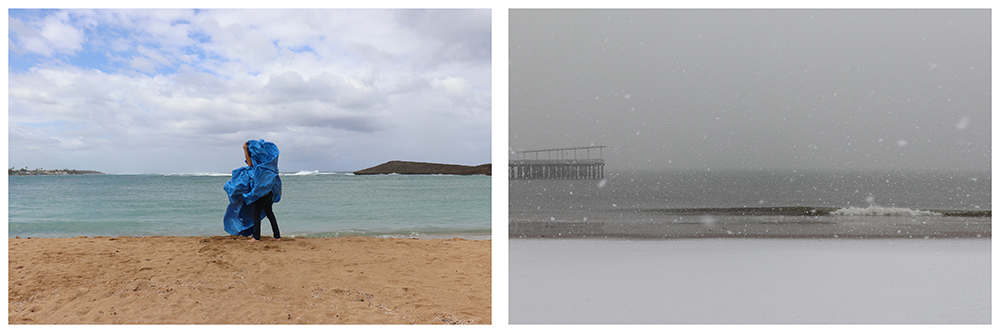

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, Carryover (Blue tarp in Vega Baja/Coney Island), 2021 (2) Digital photographs / C-prints 20 x 61 in. A diptych photography. On the left photograph, an individual covered with a blue tarp stands on the beach in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, during a semi cloudy day. On the right photograph, an empty Coney Island beach in the middle of a snowstorm. The format of each photograph creates the illusion that it is the same location and same moment during different seasons.

This week we are looking at projects by disabled/chronically ill photographers. The definition of dynamics is “forces or properties which stimulate growth, development, or change within a system or process.” Each of these artists is approaching their work in ways that embrace this meaning, enacting change and raising important questions about societal systems through their ideas, craft, and processes they use.

Kevin Quiles Bonilla (b. 1992) is an interdisciplinary artist born in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He received a BA in Fine Arts – Photography from the University of Puerto Rico (2015) and an MFA in Fine Arts from Parsons The New School for Design (2018). His work has been presented in Puerto Rico, The United States, Mexico, China, Belgium, Japan, and Greece. He’s the recipient of an Emerging Artist Award from The John F. Kennedy Center (2017). He has recently presented his work at The Brooklyn Museum, Queens Museum, The Shelley & Rubin Foundation’s 8th Floor Gallery, Dedalus Foundation, and the Leslie-Lohman Museum’s Project Space. He has been an artist in residence at Art Beyond Sight’s Art + Disability Residency (2018-2019), Leslie-Lohman Museum’s Queer Performance Residency (2019), LMCC’s Workspace Residency (2019-2020), and En Foco Inc. Photography Fellowship (2021). He explores ideas around power, colonialism, and history with his identity as context. He currently lives and works between Puerto Rico and New York.

Kevin Quiles Bonilla (n. 1992) es un artista interdisciplinario nacido en San Juan, Puerto Rico. Completó un bachillerato en Bellas Artes – Fotografía de la Universidad de Puerto Rico (2015) y una maestría en Bellas Artes de Parsons The New School for Design (2018). Su producción artística ha sido presentada en Puerto Rico, Estados Unidos, México, China, Bélgica, Japón y Grecia. Es recipiente del Premio para Artistas Emergentes de el John F. Kennedy Center (2017). Recientemente ha presentado su trabajo en The Brooklyn Museum, Queens Museum, Shelley & Rubin Foundation’s 8th Floor Gallery, Dedalus Foundation y Leslie-Lohman Museum’s Project Space. Ha sido recipiente de residencias artísticas, como Art Beyond Sight’s Art + Disability Residency (2018-2019), Leslie-Lohman Museum’s Queer Performance Residency (2019), LMCC’s Workspace Residency (2019-2020) y En Foco Inc. Photography Fellowship (2021). Sus exploraciones nacen a raíz de ideas sobre poder, colonialismo, e historia con su identidad como contexto. Actualmente vive y trabaja entre Puerto Rico y Nueva York.

What shapes our movement and image in the everyday space? What power impacts the individual in public, and in private? What histories frame us? And what culture claims or rejects us? Using installation and performance-based strategies as resources for re-signification, my current work deals with representations of the colonial subject, constantly traveling on unsolid grounds. I do so through the intersection of structures such as space, language, history and politics, with a body like mine transiting between Puerto Rico (the colony) and the United States (the mainland). Ultimately, my work seeks to unearth the construction of a queer, historic heritage, using my body as the political repository, colonized by multiple structures of power: As a Puerto Rican, as a diaspora migrant, as a person with a disability, and as a queer person. -Kevin Quiles Bonilla

¿Que elementos formulan nuestros movimiento e imagen en el espacio cotidiano? ¿Que poder impacta al individuo en público, y en privado? ¿Qué historias nos determinan? ¿Y que culturas nos reclaman o nos rechazan? Utilizando estrategias de instalación y performance como recursos para la re-significación, mi trabajo actual trata las representaciones del sujeto colonial, constantemente traversando terrenos no solidos. Hago esto a través de la intersección de estructuras como espacios, lenguaje, historia y política, con un cuerpo como el mío transitando entre Puerto Rico (la colonia) y los Estados Unidos (el ‘mainland’). En última instancia, mi trabajo busca desenterrar la construcción de una herencia histórica queer, usando mi cuerpo como repositorio político, colonizado por múltiples estructuras de poder: como puertorriqueño, como migrante de la diáspora, como una persona con discapacidad, y como una persona queer. -Kevin Quiles Bonilla

MB: Welcome, Kevin. So excited to talk about your work. To start, would you just please tell us a little bit about yourself?

KQB: My name is Kevin Quiles Bonilla. I am an interdisciplinary artist. and my work predominantly transits through the mediums of photography, video, performance, and most recently, installation. The work is very rooted around my lived experience as a Puerto Rican currently living on the “mainland” the United States. The work explores in many ways the different questions and outcomes and experiences that come with inhabiting this sort of threshold, that in-between space. And that in-between space mirrors the ideological and political experience of the island itself, being a colony of the United States, for many, many years, and so ultimately my work explores how colonialism plays a role in the different identities that we inhabit as Puerto Ricans. And so I don’t think that it just functions as a type of vacuum. You know where it affects one specific identity. I think that it just affects all the identities that we have. And so the works are in many ways a self-portrait. I’m always thinking about my identity as a Puerto Rican, as a queer person, as a person with a disability, as a person of color, as a person of the diaspora. So I think all of my works try to navigate through those questions.

MB: Can you please share with us a bit more about your art practice?

KQB: Yeah. So my art practice started when I went to college. I already knew that I was very interested in studying photography particularly, but I decided to study photography through the fine arts department. And ultimately to me, it was a really amazing decision that I made because it sort of allowed me to do an introspection and look inwards for the work that I was producing. I think that the initial ideas that I had around photography wouldn’t necessarily be about doing an introspection, but more sort of like photographing the other you know? So to me this idea of being able to see myself through the photographs, you know, it was very revolutionary. And it was that time at college where I was introduced to a lot of theories about identity, about queerness, about feminism. And so all of that was very, very formative for the practice that I have at the moment. Afterwards I decided to migrate to the United States to continue my graduate studies. Which is again another very poignant moment because this was the place where I was able to create a community of artists. But also more specifically, it was one of the first times where I got into contact within a larger community of disabled artists. And it was when I started being introduced to disability theory, which is something that I quite frankly wasn’t aware of. I knew about disability. But I didn’t know that incredible theory created around it.

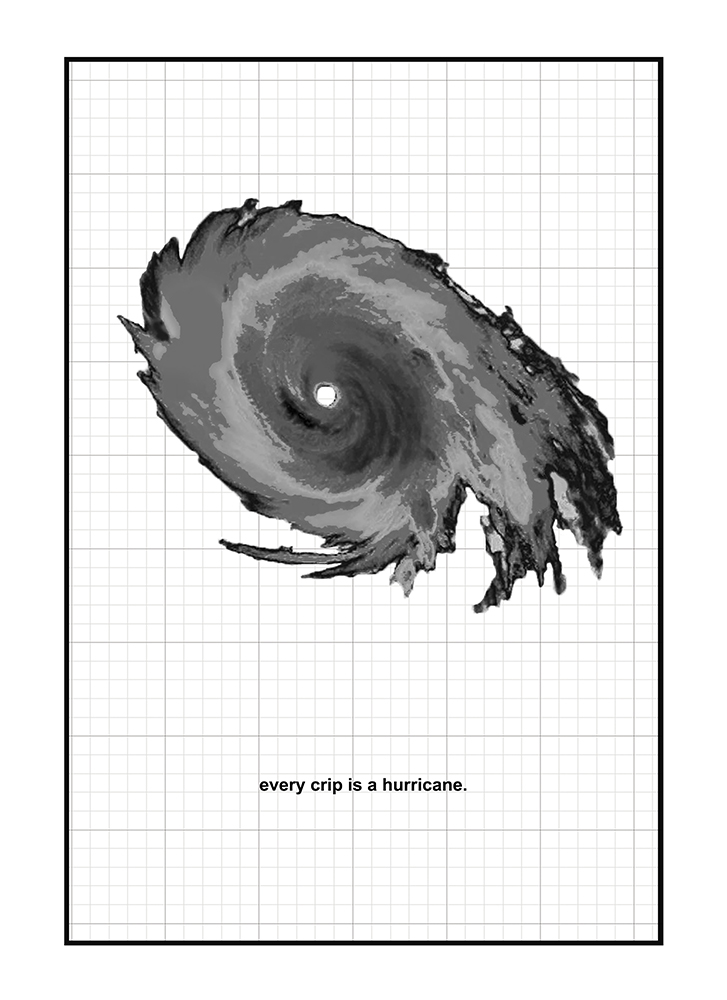

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, …is a hurricane, 2021, inkjet print on paper, poster reproductions of artwork for free distribution, 36 x 110 in. On top of a grid pattern, a radar still of Hurricane Maria (2017) is in the center, in shades of black, white and grey. At the bottom, a small, black, lowercase font reads “every crip is a hurricane”.

MB: What does disability mean to you personally, and what does it mean in your work?

KQB: I thought a lot about this one question because I think that my notion of what disability is has changed my entire life. So for a really large chunk of my life, I always reserved the idea of disability only in the physical realm, and that is due to my lived experience with my sister. So, just to give context, I have a sister that still lives in Puerto Rico. She’s a year older than me. We have really, we have been together, for a really big part of each other’s lives, and she has a physical disability. So from a very early age, she was in a wheelchair. We were together the entire time, we studied at the same schools, we would spend a lot of time together, so the experiences and the ideas that I had on what disability was were all surrounding that specific experience, so it was always within the realm of the physical.

I would say it was around when I was about 11 years old, when I started presenting the symptoms of what then became the neurodivergent disability that I have. I think that this has to do a lot with the culture and the stigma around mental disability, you know, it always has to be kept as a secret, we have to be kept to the side because it’s not visible. So “there really is no need” to present it, you know? So I don’t think I ever had a chance to even acknowledge it as a disability. Because it was always, you know, just set it to the side. It’s like this experience that you have, but then you don’t have to talk about it, so even just keeping it in as a secret, it was already this process of censorship that I was creating. And I think it just goes back to getting to know this larger community of disabled artists that has allowed me to slowly come into my understanding of my own lived experience of a disability. And still, I would say it’s a work in progress. It is still something that I’m getting used to, you know, thinking of myself as a disabled artist, as a disabled person, and in essence an artist. My ideas around disability have been ever-changing throughout my life.

MB: Do you want to share anything about your work and disability specifically?

KQB: I think one of my main interests, and I think this is overall in my entire practice, is thinking about disability. I’ve been really interested in sort of merging the ideas of colonialism and disability and thinking about how can colonialism, in many ways, function also as a type of disability? It is still a question that I think I will forever be asking. You know I don’t think that I’m near an answer yet. I think that it is something that I’m still and will forever be asking myself.

But yeah, I think that’s one of the main interests of how to think about disability not only through the experiences of the body and the mind, but also the experience that the political repercussions, you know, of a colonial lived experience. In how there’s not only the experience that Puerto Ricans, that contemporary Puerto Ricans have within specific contexts but also the generational trauma that we’ve had for hundreds and hundreds of years now of living within a colonial environment.

MB: How did you get into photography, and what compels you about the medium?

KQB: Yeah. Well, my first contact with photography came when I was in middle school. I was very lucky to take a photojournalism class. And so I get it just like right in there. It was not a fine arts focused photography class. It was always focused either on photographing others, it was always focused around either journalistic photography or commercial photography. So I never thought that I was able to sort of use photography as a tool to create an art practice. That slowly happened when I entered college, and then in grad school. And yeah, and then once I started expanding sort of my interest around photography. That’s when I also came into contact with performance art and sort of started thinking of them, you know, as these two collaborative mediums.

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, Self-portrait of a young jíbaro (collaboration with Doris Bonilla Ramos), 1996/2021 Analog photography, 11 x 14 in (Framed). An analog photograph with the date “96 12 20” on the left side. In the forefront, a small boy is dressed up as Puerto Rican jibaro. He has a large beachcomber hat, a white button shirt, a red handkerchief around his neck, a red cummerbund and black pants. He is smiling and winking at the camera. He’s holding a plastic bag in his right hand. In the background, a woman is holding a child and is looking away, a second woman is staring at something the camera doesn’t capture.

MB: So in your photographic work I’ve noticed you use vernacular/family photographs. I know that you do research and will use imagery from library archives, and then you make your own photographs that you know you are part of. I was hoping you could share more about that decision, working with all these different methods of photography and if it’s brought anything up for you?

KQB: Well, I will start by saying that I’m an absolute archive junkie. I love being able to go into an archive, it’s almost like going into the unknown. You never know what you’re gonna bump into even looking at family albums, you never know what you’re going to stumble upon. So there’s this process of sort of like hide and seek that I really enjoy in exploring, and working with these materials. Whether it is the family album or whether it is going into the archives of the Library of Congress, for example, which is a lot of what’s around the projects that I worked on recently.

But now I’m really interested in this idea of how there’s already this language, and this history that precedes us, you know, and I think that at least in my work it’s really important for me to look back and acknowledge our ancestors, the people that came before us. And to me, it’s always been a process where in looking back I produce new questions and new ideas. Looking back has always been a very regenerative process. So from looking into those archives I’m constantly creating new questions and posing new questions that allow me to create brand new photographs, and brand new work. So it is almost like this reciprocal relationship.

MB: Hearing you talk about these ongoing conversations reminds me of the circular nature of time. And it’s just really… I just love that.

KQB: Yeah. I think a perfect example of that, like one of my favorite places here in the city is The Picture Collection of the New York Public Library, you know, where they literally just cut out images from all publications. So it’s not necessarily them acquiring artwork like it happens at a gallery. It’s literally them just going through a book just cutting up images. And it’s just beautiful, it doesn’t have a specific theme, it’s just this collection of images. I know that every single time that I go in, it’s just this new find that is really beautiful.

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, Carryover (Blue Tarp in San Juan), 2018, Digital photograph / C-print, Dimensions variable. Photograph of a person with a blue tarp covering their upper body, as they lay down in a colonial wall of San Juan, Puerto Rico. They are wearing a white shirt and blue jeans. The blue tarp is getting caught by the wind. In the distance, the Atlantic Ocean and a blue sky.

MB: In your Carry Over Blue Tarp and Edge Colonial Wall series, I perceive it as a blend of performance and photography. I was wondering if you could elaborate on how you experience these two mediums (performance and photography) being in conversation.

KQB: When I started taking different courses that specifically focused on performance I stumbled upon a lot of texts and a theory around this idea of photography is the documentation of the performance. And something that I noticed right away is that there was already this hierarchy created where one had to be above the other. Because these were so performance-centered, you know it’s almost like saying, performance is the top one, and photography, it’s just a documentation, you know? Then I stumbled upon the works of, for example, very innovative artists like Carolee Schneeman, that really redefined this notion about what the documentation can be and also saying, ‘The photography, it’s powerful in its own rights, just as it is.’

The line of thinking that I have around this is I never try to think of it as one above the other. I always try to create this equal ground between both of them. I think obviously first, photography becomes a necessary tool, you know, because of those performances. For example, the Carryover series are done in very site-specific locations whether it is San Juan or my hometown Vega Alta or were produced here in New York but at the same time, I don’t, I never think of them just as the documentation of the performance. I think of them as a photograph in its own right. Of course, the performance will never be able to replicate photographs or vice versa. But still I think that we are able to try to find a common ground between both of them and that’s something that I constantly try to do whenever I merge these two mediums together.

MB: Yeah, when I look at your photographs I definitely feel there’s a level of like attention and care that comes across to me.

KQB: I appreciate that, thank you.

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, While you dried in the sand (the wind took everything), 2021, Custom print on beach towel, 38.5 x 77 in. A custom printed beach towel. In the background, a black and white image of a palm tree. In the foreground, a group of palm trees destroyed after hurricane María. On the top right there’s a flower and green leaves and on the bottom right, in pink and “tropical” font the phrase “the wind took everything”.

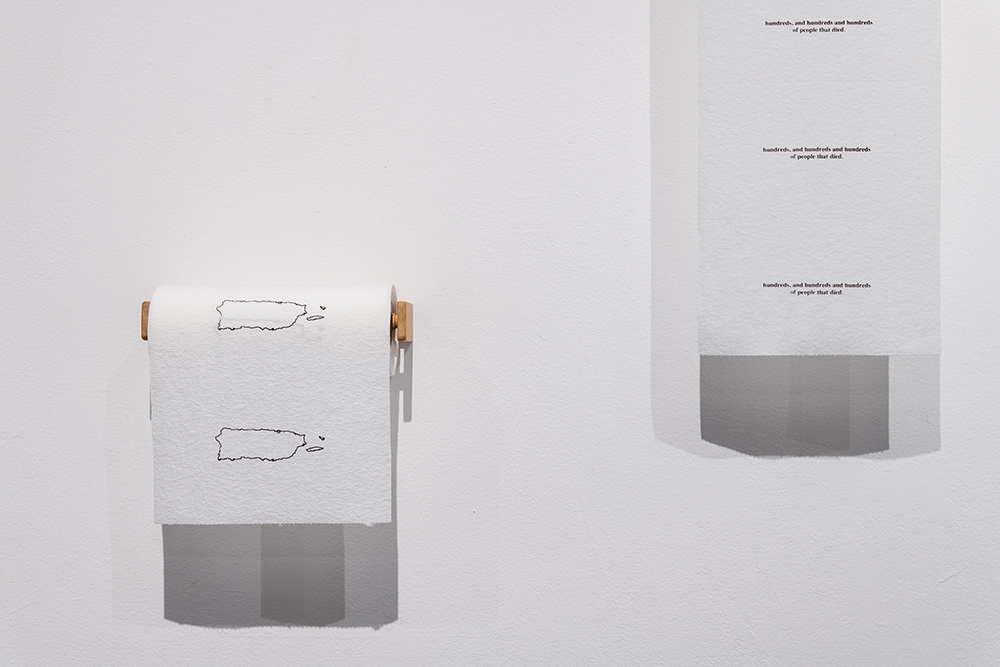

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, To absorb and contain, 2021, Silkscreen print on (11) paper towel rolls, (11) wooden paper towel holders, Dimensions variable,Installation views by John Groo. In a gallery space with gray floors and white walls, 11 paper towels are installed at different levels. Each roll has a statement printed with silkscreen on each sheet. Each paper towel is also unrolled at different levels, two of them are touching the floor.

MB: In your series To absorb and contain and While you dried in the sand you printed on, “nontraditional” materials, like paper towels and beach towels. To me, this just added another layer of meaning to your already rich work. Can you share more about why you chose these specific materials?

KQB: Well for these two projects To absorb and contain, and While you dried in this sand, the materials I printed on were very specific. So in To absorb and contain I’m specifically referencing a moment that happened right after the passing of Hurricane Maria. When the then President of the United States, which I don’t like naming, came to the island. And instead of presenting some sort of empathy that the huge catastrophe had happened, he started, comparing it to other catastrophes, such as Katrina, started talking about budgeting, and started just creating a really toxic environment. And this toxic, like this very clear separation between this is us and the Puerto Ricans are over there. In that very horrific visit, that I think was like all of 4 hours and then he went again on Air Force One and left right back to the US, he stopped at a church where they were handing out different first aid materials or household materials to different people. And he decided to start taking these rolls of paper towels and throwing them at people. And that specific image that was captured, to me it really just encapsulated all of the mishandling that happened after Hurricane Maria. You know the hurricane, the catastrophe itself was one thing, but the real disaster and the actual catastrophe really happened because of the inadequate treatment of Puerto Ricans not only by the US government but also by the Puerto Rican government itself. And so yeah, I was really interested in how this material became this very violent tool, you know, aimed at Puerto Ricans. And so I wanted to in many ways reclaim it, turn it into a reminder because I think another effect that I think is so visible in places that have endured a lot of colonialism is this sort of colonial amnesia. Where we quickly forget about all these very traumatic things that have happened to us, and it is something that I noticed very much happened in Puerto Rico right after the hurricane when the electricity came back. You know and it’s usually hidden with this desire to ‘Oh, we just need to move on.’ But it’s almost like this amnesia where people forget about everything that happened.

I think a perfect example of that, is how the current governor of the island is in the same party that got ousted from power in 2019, when it came to light, this chat room with different political figures just speaking horrible things and making fun of women, making fun of queer people, speaking really horribly about the people that passed away after the hurricane. So I was thinking about that. And I was also thinking about the different protests that happened on the island as a result of that. I started compiling this archive of different phrases that were either said by the then president, by the then Governor, phrases that were included in the different protest signs of Puerto Ricans in 2019 and present them again over and over in each sheet of the roll paper. As a reminder that even though there’s this constant desire for us to forget what has happened it is so very important to recognize it in order to truly move on.

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, To absorb and contain, 2021, Silkscreen print on (11) paper towel rolls, (11) wooden paper towel holders, Dimensions variable,Installation views by John Groo. In a gallery space with gray floors and white walls, 11 paper towels are installed at different levels. Each roll has a statement printed with silkscreen on each sheet. Each paper towel is also unrolled at different levels, two of them are touching the floor.

MB: Just hearing you talk about it now…It made me wonder…When you were printing the phrases on each sheet of each paper towel, how that in and of itself is like this durational performance. And what was it like to make that work? To go through the process of repeating and printing these phrases over and over again on each paper towel?

KQB: Yeah, it was definitely a sort of durational performance in itself. Usually, I think with performance and digital photography, their system sort of has this immediacy that happens when you do it, and especially with my performances that tend to be very quick. I don’t tend to work a lot with durational performances but it sort of took me back to these processes that include that there’s a process of labor that’s involved. Like film photography, like paper making, for example. So screen printing, which was also the first time that I started exploring screen printing, reminded me of those processes that involve this durational and this very kind of intimate relationship with the material and context. It was a very interesting experience printing these phrases over and over. It was like different emotions, you know, because when I was printing the phrases from these particular negative figures I had these feelings of rage and anger that they were said, but then, when I started printing the phrases of the Puerto Ricans, it sort of reminded me of how amazing that time was that specific period was, because it was the first time that I truly saw Puerto Ricans demanding, like truly demanding, change. Yeah, so it was just a mixture of feelings and emotion.

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, While you dried in the sand (it came out of nowhere), 2021, Custom print on beach towel, 38.5 x 77 in. A custom printed beach towel. In the background, a view of green mountains in Puerto Rico. On the foreground, an aerial view of houses with blue tarps after hurricane María. On the bottom left, there’s a couple of flowers and on the top left, in multicolor and “tropical” font the phrase “it came out of nowhere”.

I wanted to also speak about While you dried in the sand, with this series that is still ongoing I was focused more on the materials that are turning into commodities specifically within tourist driven locations. And so this project came from memories of me for a really long time going to San Juan, which is Puerto Rico’s capital, specifically Old San Juan, one where there’s all of this there’s many many many stores that specifically target tourists. So they have all these little tchotchkes and souvenirs of Puerto Rico that tourists can take with them and I was particularly really interested in the very extravagant, very stereotypical, and also slightly kitsch language that’s created around these materials. You know it’s like there’s always this very specific imagery, this very specific colors, and fonts, you know? And so I wanted to play and appropriate that language and play with it and not only thinking of them as these commodities, but I think of them also as tapestries.

And so I decided to turn, to invert, this language and turn it again into thinking of these artworks as reminders. You know I decided to then present the recent history of the island and the moments that have been very poignant for the current context of the island. So everything from the passing of Hurricane Maria, the protests in 2019, the earthquakes in 2020, and then the constant protests that have been happening even beyond 2019. So that’s why I say that in many ways I think of them as tapestries because it’s almost like an archiving of this very specific history through this stereotypical language that is often given to tourists as a sort of ‘Oh, this is how we are.’ So this is the presentation of these are the actual things that are rattling while you dried in the sand.

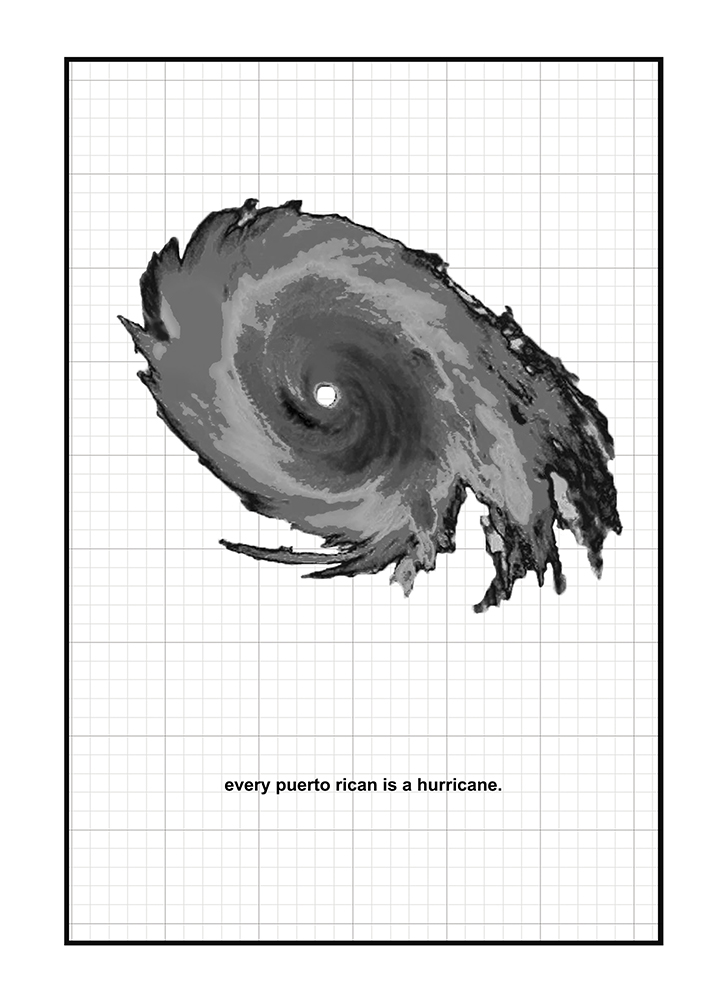

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, …is a hurricane, 2021, inkjet print on paper, poster reproductions of artwork for free distribution, 36 x 110 in. On top of a grid pattern, a radar still of Hurricane Maria (2017) is in the center, in shades of black, white and grey. At the bottom, a small, black, lowercase font reads “every Puerto Rican is a hurricane”.

MB: I love your …is a hurricane series, and I was hoping you could share more about those posters, and the impetus for making them.

KQB: So with …is a hurricane I am again referencing the protest of 2019. To me, it was such a poignant moment where I truly, I think I’ve never seen Puerto Ricans coming together for one specific thing. There’s always either ideological differences there’s always been some type of difference between the different sectors of the island, and so to me this was the first moment in which I saw this actual unification of the island, and just to see women, people with disabilities, and queer people at the forefront of the protest was also so incredibly revolutionary. And also younger people that were the ones on the frontline. And yeah, queer, trans, gender non-binary people were all at the forefront of that. It was really such a revolutionary moment, and to me, it was the moment in which Puerto Ricans truly became hurricanes themselves.

For a really long time, I had that image of the hurricane. It was taken off of an actual radar image of Hurricane Maria, as it was passing over Puerto Rico and you know It’s focusing a lot of obviously the very specific trauma that is connected to this imagery of the hurricane. You know, and not only this hurricane, but the long history of hurricanes that have passed through the islands. I always talk about this, there’s this history, you know my grandma has experienced a hurricane, my mother has experienced a hurricane, I have experienced a hurricane, you know, and I think it’s like this sequential thing – of all of us haven’t experienced this.

Going back to what happened on the island afterwards, I really want to try to create this separation between Yes, we experienced this hurricane, and it was a catastrophe, but you know the catastrophe that I feel that we really should focus on is the inadequacies that happen after it, which actually created the more longer-term problems on the island. And so, and it’s like I wanted to rethink the notions that I had about the hurricane, and not think of it only as this negative connotation but also how it can be turned into a symbol of power and resistance. And so I was thinking about it and to me, these are protest signs, which is why I created duplicates for people to take when they saw the work so the message would go beyond the gallery walls. And here, in particular, I’m referencing the identities that I inhabit that often can or are seen as as marginalized identities: so my Puerto Rican identity, my queer identity, and then my disabled identity. And I think that all of us in many ways, there are many moments in which we need to become hurricanes in order to to demand change. I think that historically you know there’s this whole history of queer communities, Puerto Rican communities, and crip communities coming together and demanding change and so it’s also an honoring to those communities.

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, …is a hurricane, 2021, inkjet print on paper, poster reproductions of artwork for free distribution, 36 x 110 in. On top of a grid pattern, a radar still of Hurricane Maria (2017) is in the center, in shades of black, white and grey. At the bottom, a small, black, lowercase font reads “every queer is a hurricane”.

MB: In our conversation a new question came up for me. I was wanting to hear more about the blue tarp and I was wondering if you would talk more about what the blue tarp means to you?

KQB: So yeah, so with the blue tarp, to me it means hiding and unhiding. It means, you know, both anonymity and the referencing of a collective So the blue tarp became such a specific and very iconographic material in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. So these tarps are given to people that suffer any type of damage in their houses by FEMA. And it was always meant to be this temporary solution that would eventually then become a longer-term solution. But that help or that solution never arrived. And you know, I think that Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria is composed of so many like specific images for example, the throwing of the towels, protests that were happening at nighttime, and another image that I think is that is synonymous with that is aerial images of the island – different communities – where all of the houses everything is covered in blue. And I myself, you know, the first time that I arrived, that I went to Puerto Rico after the hurricane it was very shocking, as you’re descending you see the blue tarps covering thousands and thousands of houses. So that’s what motivated me to start engaging with this material performatively, and thinking about not just the home as the precarious site, but also thinking of the body as a precarious site.

I think that collectively, we endured so much trauma with this event, not only the people that experienced the hurricane while on the island but everyone in the diaspora that has such deep connections to the island. All those days, weeks, that we weren’t able to communicate. So I think that all of us share a certain level of trauma with this event. And so I wanted to think of the body as the precarious site that needed some sort of protection, and that’s what motivated me to interact bodily with the tarp. And so I started in Puerto Rico, and locations like San Juan, with the colonial walls. And then more personal places like you know the area of green in front of my house where my father planted some plantain trees, you know, and then I moved to also referencing the experience of the diaspora community, and I started photographing myself in New York City.

So I think at the core of that work is, while I’m using my body I’m always conscious of covering my face because in my work I don’t see that entity as myself, but rather as a collective. So the reference is of a collective, and I think that is something that I have done in my work a lot. I always use my body but I’m always trying to hide my face either by putting on the mask, by putting on a tarp by just not showing my face, and it’s the creation of this collective, this idea of a collective. I always really love how artists like Joiri Minaya talk about the creation of an archetype.

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, Carryover (Blue Tarp in Vega Alta), 2019, Digital photograph / C-print, Dimensions variable. Photograph a person standing in a field with three plantain trees of different sizes around them. Their body is covered with a blue tarp, exposing his left hand and legs. They are wearing a white shirt, blue jeans and a multi color bracelet.

MB: Who are some artists that have influenced you and your work?

KQB: So obviously, there’s always these canonical artists you know that we all sort of look up to, you know. In my case you know artists like, Ana Mendieta, Felix Gonzalez Torres, Liu Bolin, Carolee Schneeman but I think something that I also started recognizing that I think is so important is that we’re, also we’re all part of a community and we’re constantly being influenced by our colleagues. So I think my artwork is also very very influenced by my community here, artists like Alex Dolores Salerno, Ezra Benus, Shannon Finnegan, Jerron Herman. People that I really care for, because they’re my friends but I’m also constantly enamored with the work that they’re producing, and seeing the questions that they pose on their work make me also create questions for myself. And so it’s again this reciprocal collaboration, you know where we’re exchanging information, you know. So I’m constantly influenced by my community of friends and fellow artists, and also my mentors. You know the professors that taught me in college, in grad school, that I still hold very, very near and dear to my practice.

MB: Following your work I see that community, that inter dialogue, and that care playing out. Which is really beautiful.

KQB: Yeah, so I actually, I was speaking recently to Ezra well not recently, in December- but I was speaking to Ezra and I was saying how me, him, and Shannon, we started doing sitting pieces, you know, in one way or another. And I was like we should unite our 3 sitting pieces and see what happens. It’s really beautiful to see that interconnection, you know?

©Kevin Quiles Bonilla, While you dried in the sand (out of the blue), 2021, Custom print on beach towel, 38.5 x 77 in. A custom printed beach towel. In the background, an aerial view of a beach. In the foreground, an aerial view of houses flooded and destroyed after hurricane María. On the bottom left there’s a sea star and on the top right, in orange and “tropical” font the phrase “out of the blue”.

MB: What are you working on now? And is there anything new and upcoming that you want to share?

KQB: So I’m currently working on my first solo show in New York City which will be at Wave Hill Garden Cultural Center in the Bronx. And it’s gonna be a site specific expansion of the piece While you dried in the sand.

MB: Congratulations!

KQB: Thank you so much. if you find yourself in New York between May and July please come out. Yeah, so that’s mainly the one I’m focusing my time on at the moment.There’s a few things coming later on but for right now, I’m very focused on this new baby.

Megan Bent is a lens-based artist interested in the malleability of photography and the ways image-making can happen beyond using a traditional camera. This interest started to occur after the diagnosis of a progressive chronic illness. Drawn to image-making processes that reject perfection, accuracy, or any certainty in results, she is interested instead in processes that reflect and embrace her disabled experience; especially interdependence, impermanence, care, and slowness

Her artwork has been exhibited nationally at The Halide Project in Philadelphia, PA, The Center For Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, CO; The East Hawaiian Cultural Center/HMOCA in Hilo, Hawai’i; Flux Factory in Long Island City, NY; El Museo Cultural, Santa Fe, NM; The Foster Gallery, in Dedham MA; Soho Photo Gallery in Tribeca, NY; the Austin Central Library Main Gallery in Austin, TX, and internationally at F1963 in Busan, South Korea; Alternative Space 298, Pohang, South Korea; and Fotosotrum in Barcelona, Spain.

She is currently an artist in residence at Art Beyond Sight’s Art + Disability Residency and has been an artist in residence at the Nobles School in Dedham, MA, and the Honolulu Museum of Art, HI. She has presented her work at Atlas Obscura: The Secret Arts, The Pacific Rim International Conference on Disability and Diversity in Honolulu, HI, at Other Bodies: (Self) Representation, Disability and the Media at the University of Westminster in London, U.K., and at Critical Junctures at Emory University in Atlanta, GA. Her work has been featured in Analog Forever Magazine, Fraction Magazine, Too Tired Project, Rfotofolio, and Float Photography Magazine.

Follow Megan Bent on Instagram: @m_e_g_g_i_e_b

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026