Interdisciplinary Approaches in Photography: Christopher Pekoc

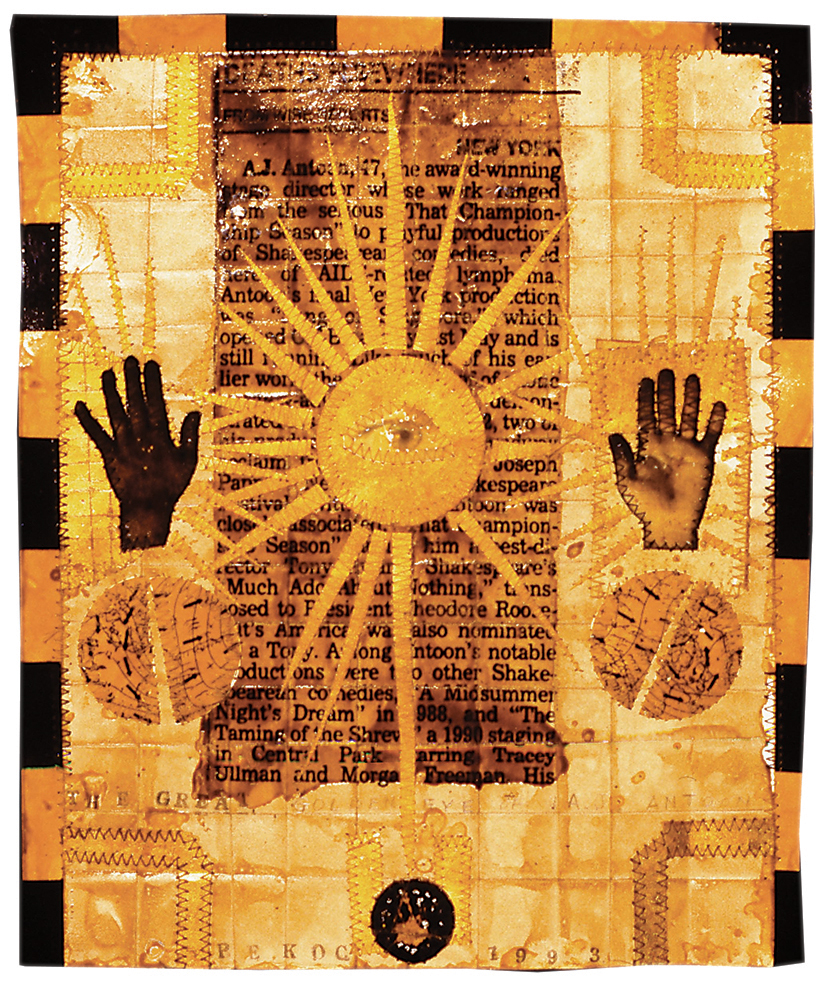

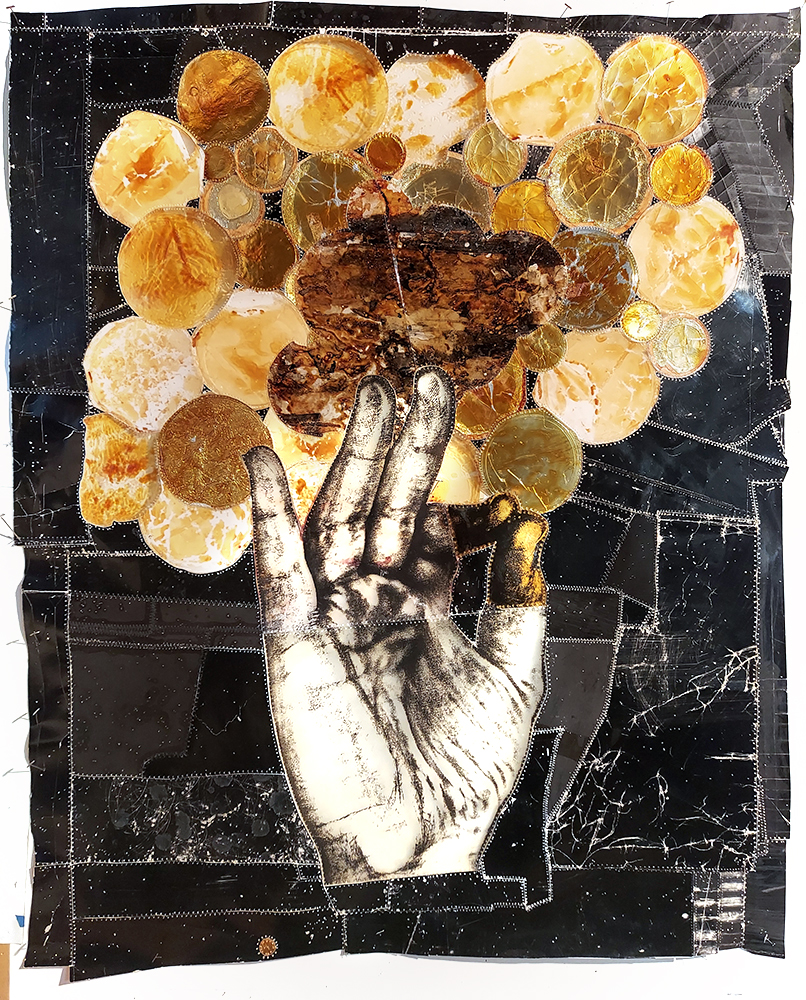

© C. Pekoc – “The Great Golden Eye of A. J. Antoon” — 11 ⅜ ” H x 9 ½ ” W — Mixed media assemblage of electrostatic prints on paper, shellac on various papers, machine stitching. Private collection.

This week, all of the artists that I am featuring take photography beyond what it is or what it is perceived to be, to what it can be. There are a wide range of themes such as family, culture, loss, history, memories, biblical stories, mythology, film and community among others. For all of these artists, the photograph is the starting point, not the end result. Beyond photography, their approaches incorporate painting, stitching, alternative processes, object making, sculpture, installation and even community engagement. Each of them employ process and content that creates a uniquely personal style of photography that demonstrates extraordinary vision.

I discovered the wonderfully unique work of Christopher Pekoc several years ago when we came to Cleveland for the Society for Photographic Education’s national conference. We spent a few hours at the Cleveland Museum of Art on our last day in town. The exhibition was called Beyond Truth: Photography after the Shutter. A handcrafted, sewn-together image of a nude male figure that combined photography and painting captured my attention. I was immediately struck by the fact that this piece of art called Portrait of Q with Thorns, was deconstructed by cutting and then reconstructed with stitching. Much of Christopher’s work is inspired by Biblical stories and Greek mythology. His imagery and process left me wanting more. I bought a catalog of his work in the gift shop that day because I didn’t want to forget the work, and I haven’t.

Christopher Pekoc was born in Cleveland, Ohio. He is self-taught except for some drawing instruction in high school and his freshman year in college at Kent State University, Ohio.

At Kent in May 1970, he witnessed the killing of four students by the Ohio National Guard and painted a large surrealistic “History Painting” of the event following the examples of Picasso’s “Guernica” and Gericault’s “Raft of the Medusa.”

Pekoc’s unusual mixture of photography and other media has quietly attracted the attention of an international group of discriminating collectors. As a young man, he worked in his family’s fourth generation hardware business in Cleveland and attributes his interest in the art of assemblage and some of the tools he uses to fashion his work to the early exposure to tools and construction projects he received in the hardware store. In his cramped basement studio, he works with an unusual array of implements including a blow torch, hole punches, hammers, pins, sandpaper, steel wool, and a sewing machine along with the more traditional brushes and paint to fashion components of his collages.

Pekoc participated in more than 110 solo and group exhibitions in the U.S., Japan, Australia, the Czech Republic, and Germany. He is the recipient of the 2007 Cleveland Arts Prize, five Ohio Arts Council (OAC) Individual Artist Fellowships and a two-month International Residency in the Czech Republic jointly sponsored by the OAC and the Center for Contemporary Art, Prague. From 2002 through 2008, five pieces of his work were displayed in the offices of the Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, D.C.

His work appears in public collections that include museums, libraries, and universities. Among these are the Art Institute of Boston, the Butler Institute of American Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Akron Art Museum, the Czech Center of Photography, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Harvard University’s Fogg Museum, the George Eastman House, The Oakland Museum, The Rochester Institute of Technology, and the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida. He has work in corporate and private collections in the U.S., Europe, and South America.

Pekoc recently retired from teaching in the Art Studio Department at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. He lives and maintains his studio in Cleveland.

“Pekoc in his studio with his assistant Maria and his cat Mo. photography by Catherine Young, The Cleveland Public Library”

“Since the invention of photography, when early daguerreotypists literally breathed color onto delicate metal plates in order to heighten the reality of their portraits, artists have turned to a hybrid form of photographic production combining photography, painting, and drawing. The art of hand tinting and hand painting photographic images continues to be employed at the present time, albeit for new and very different reasons. An understanding of the lasting appeal of hand-altered photography is important to the study of photo history and contemporary photographic art itself.”

– Alida Fish, September 2003, Professor of Photography, The University of the Art, Philadelphia

I began working seriously as an artist in the mid 1960’s. At that time, I took photographs to aid me with my portrait and landscape drawings and later used collages fashioned from photographs found in magazines as studies for my paintings. The drawings and paintings were exhibited, but, because I thought of my photographs and photo colleges as studies, they remained in the background.

In 1988 my focus changed, and photography became central to my work. I am not a traditional photographer. I use a camera and at times a photocopy machine to capture and process an image. My past experiences with drawing and painting dramatically shapes how I will use that image. For me, the photograph is only the beginning of a long and complex process that developed over time and allows me to uniquely shape each of my photographs, guided by my past artistic experiences as well as my imagination and intuition (intuition plays an important role in my work –I do things because they “feel” right). I wanted to pull my photographs as far back into my past world of drawing and painting without allowing them to completely lose their photographic essence. And, since life itself is not perfect, I attempt to mirror life in my work by including edited accidents and imperfections in the composition.

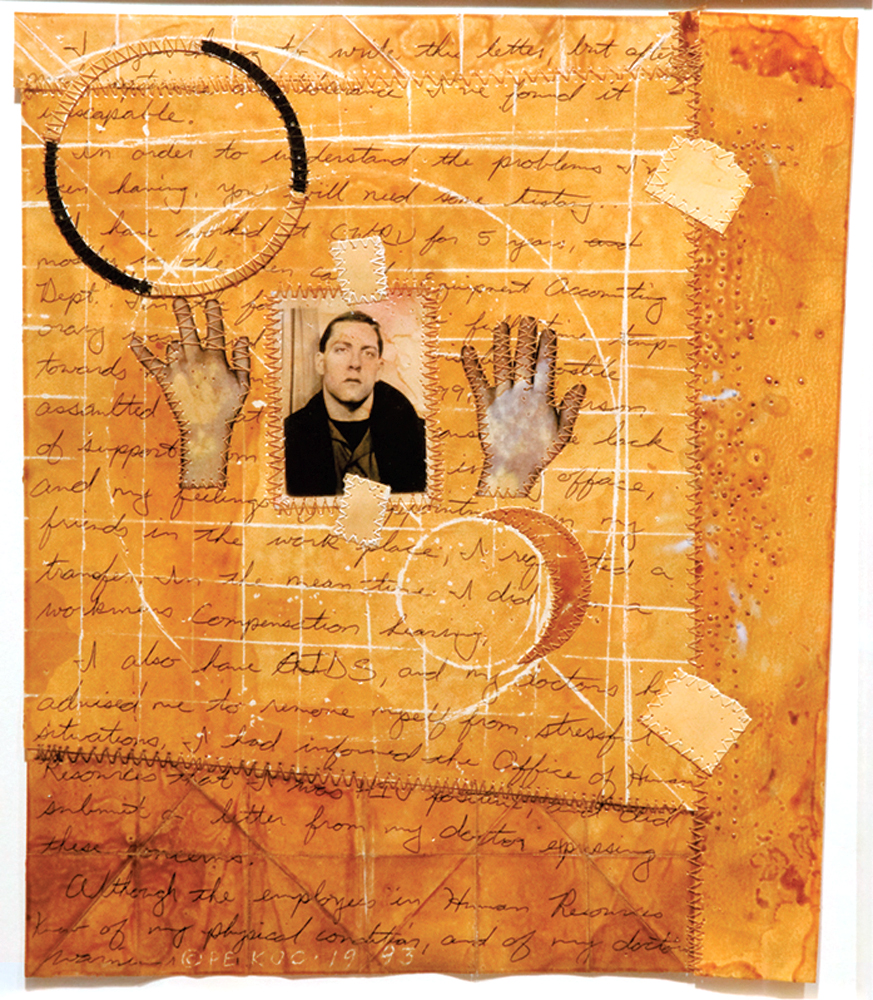

I begin by photographing my subjects in front of a neutral background without any notion of how the image will appear in the final composition. I am attracted to the human form and use it for much of my work. The figure is something we all relate to as well as being the “yardstick” with which we measure the world around us. I am also interested in hands perhaps because I have always found working with my own hands gratifying (some of the first images that humans made, found on the walls of caves some 40,000 years ago, were of their hands). And I sometimes use what those hands have written because the written word flows directly from our thoughts and our thoughts define who we are. They determine our actions. The sum of our acts, often carried out with the help of our hands, written or otherwise, provide a more definitive portrait of an individual that the outer contours of the body.

After losing darkroom privileges at the University where I was teaching, I began using a photocopying machine to process my imagery. It became my darkroom and at times my camera. The copy machine has 27 settings that can capture, enlarge/reduce, and lighten/darken an image. After electrostatically printing my photograph onto either paper or transparent film, I laminate it. The laminate consists of polyester film, a tough, transparent material that does not break down over time. It protects the image and makes it sturdy enough to be sewn. Then I cut it out.

To add elements of drawing and painting and include references to life’s imperfections, I “damage” the image in a combination of ways, and, using an odd array of hardware store implements, I fold, wrinkle, scratch, sand, perforate, and coat it with paint, varnish, shellac and/or metal leaf. This handwork adds character to the photograph, making it unique. Then I select accompanying images and a background from the vast inventory of paper and polyester film that I have prepared in a similar manner. The pieces are pinned to one of the large bulletin board walls in my studio. The pins allow shapes to be freely moved about as I refine the composition.

I begin to explore composition possibilities with only a vague idea as a guide and the hope that I will arrive at an image that is both striking and memorable. Inspiration comes from several sources. Two important ones are: Greek mythology or Biblical stories because those engaging ancient tales are filled with exotic personalities and life’s lessons still relevant today. I am also inspired by the beauty of the natural world and celebrate it in my work in response to the threat of global warming. The mental image I carry is enough to get me started and it will shift and change as the artwork progresses. I rely heavily on trial-and-error — elements and ideas are discarded as better ones present themselves and accidents often provide welcome surprises. The relationships between the various parts remain in a state of flux until the composition “feels” finished. At that point, the parts are cut and fit together, and the entire composition sewn with a sewing machine into a single piece.

The path to a finished piece is often slow and unpredictable and it is not unusual for my pictures to develop over several months or even years.

The stitching serves three purposes, it makes the artwork whole and provides a distinctive textural element to its surface. It is also symbolic and acts as a metaphor for our own psychological damage and repair. Damage that occurs as we struggle with life’s burdens and the repair necessary to overcome them. C.P. 5/06/2022

© C. Pekoc – “Portrait of Jan Saudek, Blue, with Bees” — 36 ½” H x 36” W — assemblage of laminated painted electrostatic prints on paper, metal leaf on polyester film, laminated electrostatic prints on transparent film, shellac, machine stitching. Private collection

GB: Tell us a little bit about your childhood and how you became an artist.

Genetics and my early childhood experiences helped to lay the foundation for my creative efforts. A marching band leader/composer (music and visual art skills often go together) and two amateur artists are in my recent ancestry.

Because I was the first of seven children my mother had the time to read to me and tell me stories inspired by classical music that we would listen to. This stimulated my imagination at an early age. Later, I showed promise and occasionally won awards in the art classes I took in grade, middle, and high school. And, in my early teens, my maternal grandmother, an amateur artist, introduced me to oil painting as we worked together copying paintings by Corot and van Gogh.

I was a troublesome teen, uncertain who I was and how I fit in. I dropped out of school at 15 and worked in my father’s and grandfather’s hardware store. A year later I returned to a Catholic all-boys high school where I tested high in creativity, received a third-place award in a city-wide High School architecture competition, and was transferred from a disciplinary study hall to the schools only art class where I did well.

These experiences, parental support, a natural ability to work with my hands and the fact that I found imaginative thinking far more rewarding than purely rational thought, helped to cement my desire to be an artist.

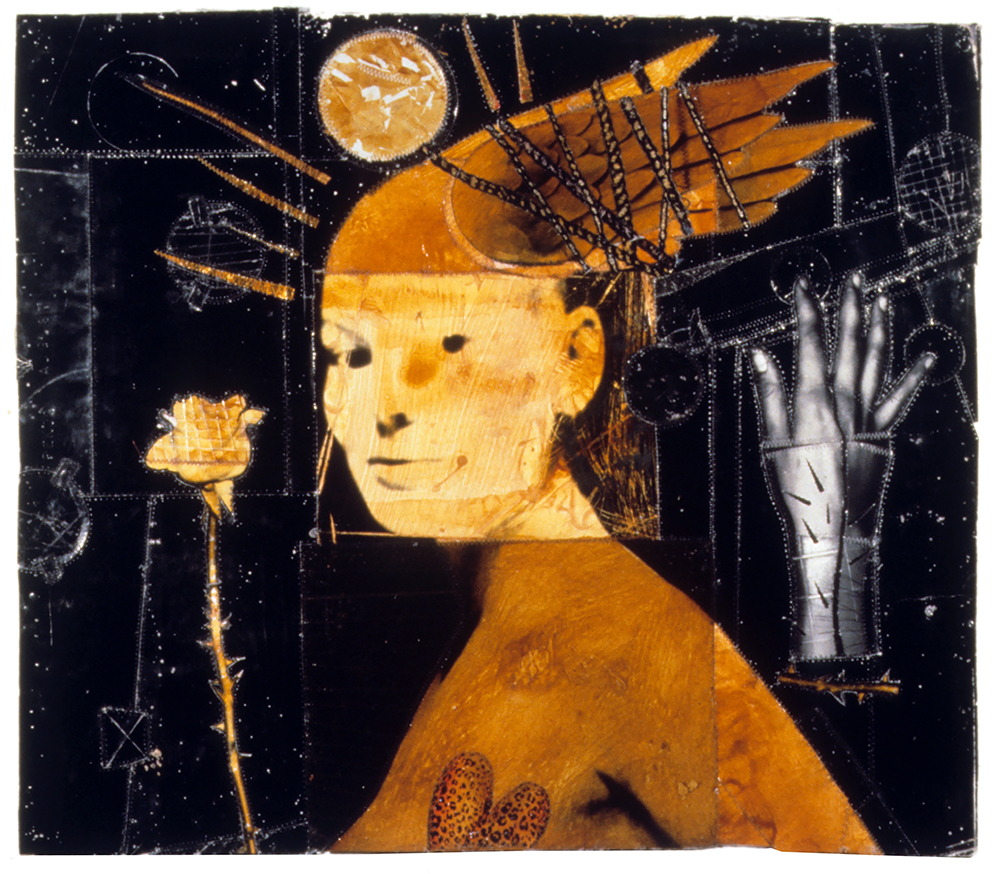

© C. Pekoc – “Queen of the Nile” — 19 ½”H x 17 5/8” W – mixed media assemblage of gelatin silver print, shellac, paper, polyester film, metal leaf, machine stitching. Collection of the artist.

GB: Can you talk about the transition from use of photography for your paintings and drawings to the use of photography as a vital part of your work?

I did well with drawing in school and had the desire to explore the medium further on my own. Over a two-year period, after dropping out of college after my freshman year, I produced a series of pencil drawings based on photographs that I took with a black and white Polaroid camera. The photographs provided the foundation for my drawings, they were my drawing “sketch book”, and the drawings received several awards in competitive regional exhibitions and led to solo shows at a regional museum and two university galleries.

Thinking that I had taken drawing as far as I could, I had the desire to leave black and white behind and enter the world of large colorful paintings. I relied on my imagination for the subject matter for this new work and turned to realizing my thoughts by making collages – the beginning of my use of assemblage – from images I cut from color magazine photographs. The collages became the “studies” for the paintings and, as with drawing, photography continued to form the foundation of this work although these photographs were by others.

My painting efforts went on for over a decade and included a 30-foot x 20-foot mural in the main hall of the Cleveland Public Library’s primary location.

As with the drawings, painting eventually ceased to challenge me. I found the making of the preliminary collage studies far more challenging than the tedious, time consuming, process of duplicating those images in paint and began looking for a process that produced a result that combined both collage making (assemblage) and photography. This led me back to the beginning: taking my own photographs and making those photographs a central part of this new work.

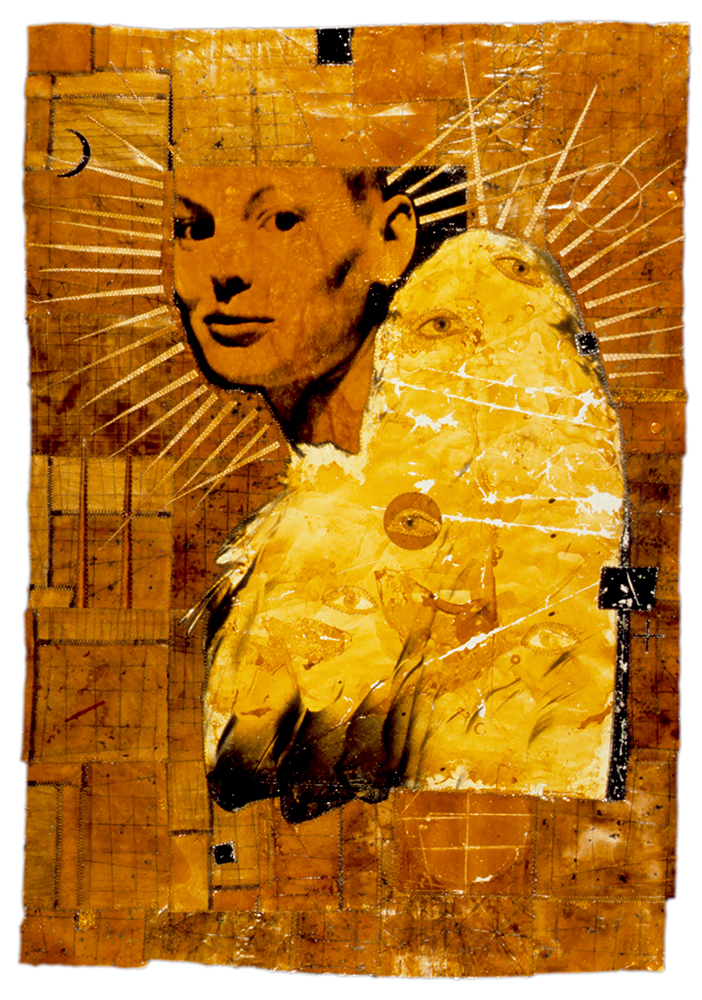

© C. Pekoc – “Portrait of K. as One of the Guardians” — 32 5/8” H x 23” W — Mixed media assemblage of gelatin silver and electrostatic prints, paper, shellac, metal leaf, machine stitching. – Private collection.

GB: Your process is very mysterious and experimental. While it is tactile, the work also combines a lot of different media, tools, painting, and photography. What would you tell someone about it who has never seen your work before?

My current work is influenced by my previous experiences with photography, drawing, collage (assemblage), and painting as well as my exposure to tools and construction projects while working in my family’s hardware store in my teens and early 20’s. The construction projects showed me that disparate elements could be assembled into a cohesive whole and led to my use of assemblage.

The unusual array of implements and materials I use in my work come from my hardware store experience. They include a blow torch, hole punches, hammers, pins, sandpaper, steel wool, shellac, wood stains, and varnishes. I also use a sewing machine (to attach the disparate elements together) and the more traditional paint and brushes along with my photographs, laminated electrostatic prints, polyester film, various papers, metal leaf, and food seals.

© C. Pekoc – “Portrait of K. with the Planets” — 24 ¾” H x 28 ½ ” W — Mixed media assemblage of gelatin silver and electrostatic prints, shellac, paper, polyester film, metal leaf, machine stitching. Collection of the Akron (OH) Art Museum.

GB: One of the reasons I think I relate to your work so much is the mythology. What is it about these Greek and Biblical stories that you draw inspiration from?

Greek mythology and Biblical stories are filled with exotic personalities and life’s lessons still relevant today. They provide my active imagination with plenty of raw material to work with.

© C. Pekoc – “Joined III with Bees” –: 40 3/4” H x 32 3/4” W – mixed media assemblage of laminated electrostatic prints on transparent film, laminated food seals, polyester film, shellac, metal leaf and machine stitching. Private collection

GB: Why and how do you take images apart and stitch them back together?

Taking images apart and sewing them back together becomes necessary when I think I have finished a piece and then realize that it is lacking and needs additional imagery to make it successful. This is a laborious and time-consuming process and I try my best to avoid it. Redoing something you have already put hours into is never rewarding.

Removing the stitching isn’t so difficult, the hard part is sewing things back together. The sewing machine needle must go through the same holes it went through when it was originally sewn. There can be hundreds, perhaps thousands of needle holes to go through. If the same holes are not used the sewn edges become frayed, weakened, and produce an unpleasant, distracting visual effect.

An example of this took place with “Shadows, the Chinese Room Remembered in Red, Čimelice Castle, the Czech Republic”. “Shadows…” is 5 ½ feet high, and after stitching the foreground images in place I realized that if I added a life-sized shadow/silhouette of myself in the background it would improve the composition and symbolically place me in the Chinese Room (so called

because of the Chinese motifs painted on the walls) in Čimelice Castle in the Czech Republic. I lived in the castle with 14 other artists from around the world during a two- month residency there.

To accomplish this the stitching securing much of the imagery already in place had to be removed. Then my shadow shape was cut out of a darker red stained paper than the red of the surrounding background and inserted into the composition. Then – the hardest part – everything was sewn back together through the original needle holes.

© C. Pekoc – “In Memory of Paul” — 11″ H x 9 ⅝” W — Mixed media assemblage of electrostatic prints on paper, paper, shellac, machine stitching. — Private collection.

GB: Is there something that you want to experiment with that you haven’t?

I like using thrown away things in my work in a way that elevates them and gives them a surprisingly new life. I have used shellac coated food seals to form the background of “Joined with Bees” and the cloud image in “Catching a Cloud” and I am always looking for new materials to work with. Lately I have been laminating the colorful net bags containing vegetables and fruit found in supermarkets. I plan to use them as backgrounds for new work but presently have no idea what I will do with them. Stay tuned.

© C. Pekoc – “Aloft V, Bird with Ellipses” – 17 ½” H x 13” W – mixed media assemblage of laminated electrostatic prints, polyester film, paper, shellac, pigmented varnish, machine stitching. Private collection.

© C. Pekoc – “I Heard the Noise of Wings” — 19” H x 19 ½” W — Mixed media assemblage of shellac on laminated electrostatic prints, paper, polyester film, metal leaf, machine stitching. – Private collection.

© C. Pekoc – “Shadows, The Chinese Room Remembered in Red, Čimelice, Czech Republic” – 65 ½” H x 30 ½ W — mixed media assemblage of laminated shellac coated electrostatic prints backed w/ metal leaf, paper, machine stitching. Private collection.

© C. Pekoc – “Catching a Cloud” — 38” H x 30 ½” W – mixed media assemblage of laminated electrostatic prints, laminated shellac coated food seals, paper, and machine stitching. Collection of the artist.

Greg Banks is a photo-based artist and lecturer at Appalachian State University. He received his MFA in photography from East Carolina University in May 2017. He received a B.A. in photography and a B.A. in fine art from Virginia Intermont College in 1998. Greg combines everything from IPhone images to historic 19th century processes, gelatin silver printing, painting and digital printing. His current creative practice investigates family, folklore, memories, magic, history and religion in Appalachia.

Follow Greg Banks on Instagram: @gregbanksphoto

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026