Medium Festival of Photography: Anna Garner

In early May 2022, I was extremely fortunate to participate in this year’s Medium Festival of Photography. Every year, the folks at Medium host an event featuring workshops, lectures, and portfolio reviews–all of which, in their words, are “fueled by passion, spirited kindness, and unswerving dedication to creative expression through photography.” As a first-time participant, I can affirm that they certainly deliver. Over the course of two days as a portfolio reviewer, I was impressed by the quality of work presented to me by a variety of talented artists. For the next few days, we will be looking at some of the highlights of my reviews. Today, I am excited to share a conversation with Anna Garner.

Just Below (excerpt) from Anna Garner on Vimeo.

Anna Garner’s work combines performance, sculpture, photography, and video to construct fictional spaces and performances for the camera. Her practice manipulates the documentary capacity of the camera to present contemplations on physical uncertainty and examine visual hierarchies within nature, gender, and architecture. Born in New York (1982) and raised in San Diego, Anna currently lives in México City. Her work has been presented at ltd los angeles, Los Angeles, CA (2019), Simone Subal Gallery, New York, NY (2021), Guadalajara 90210, México City, MX (2022) Museum aan de Stroom, Antwerp, Belgium (2019), The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC (2019), and The Phoenix Museum of Art, Phoenix, AZ (2016). Anna’s work has additionally been supported through residencies at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (2014), Bemis Center for Contemporary Art (2016), Art OMI (2019), and Lighthouse Works (2022). In 2014 she received an MFA at The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ.

Follow Anna Garner on Instagram: @anna.b.garner

My studio work combines performance, sculpture, photography, and video to construct fictional spaces and performances for the camera. I utilize unstable forms and materials, engage vulnerable actions, and highlight the fiction of my constructions, to create states of uncertainty for both the body and the image.

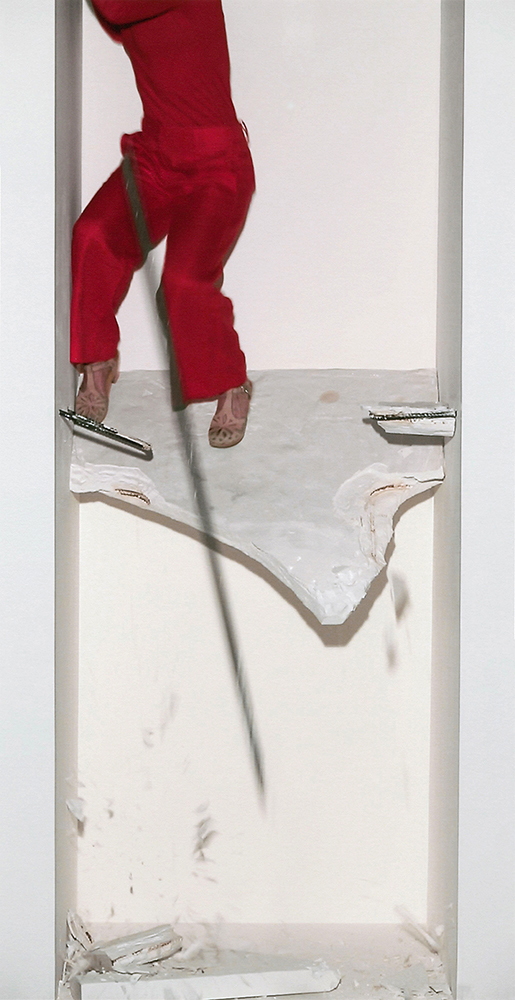

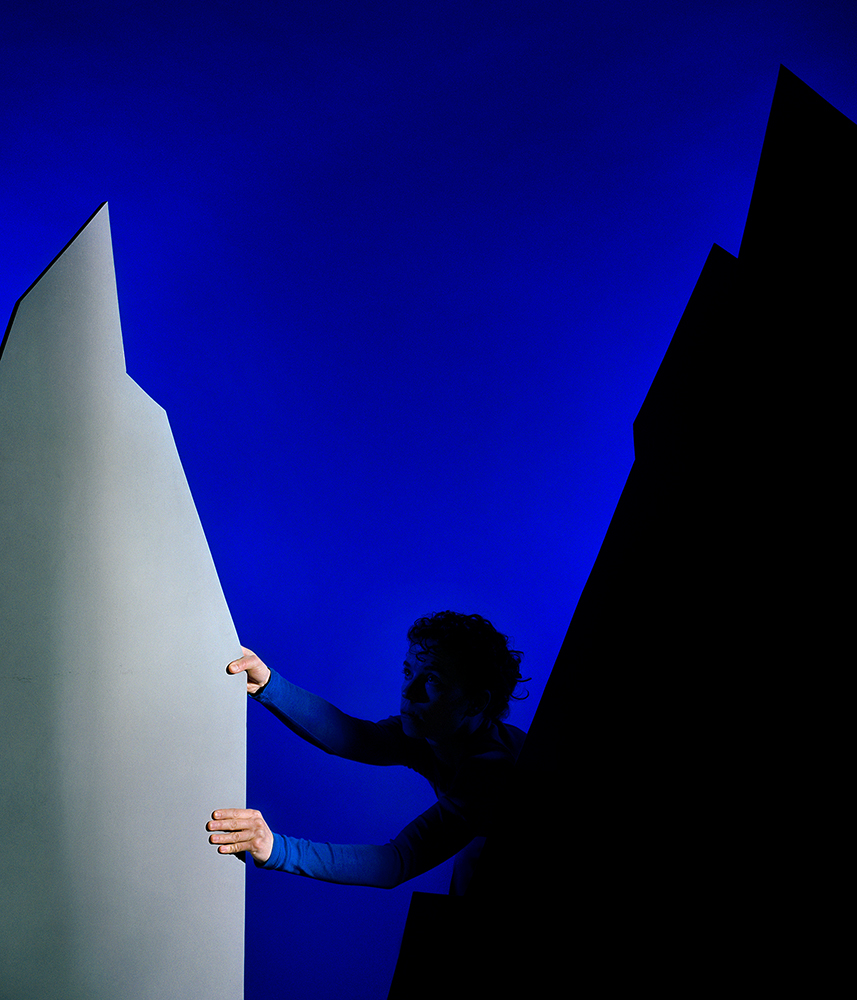

In performative videos and photographs I physically engage and enact representations of strength, risk, and vulnerability. The performative actions, which include, causing myself to fall, moving mountains, and lifting a bodybuilder, take place within constructed sculptures, installations, or studio sets. Employing the simplistic forms and dramatized lighting of theatrical set designs, I emphasize the frame of the camera as a stage for invention and manipulation. My performative interventions deconstruct the documentary capacity of the camera, while reorienting visual hierarchies between nature, gender, and architecture.

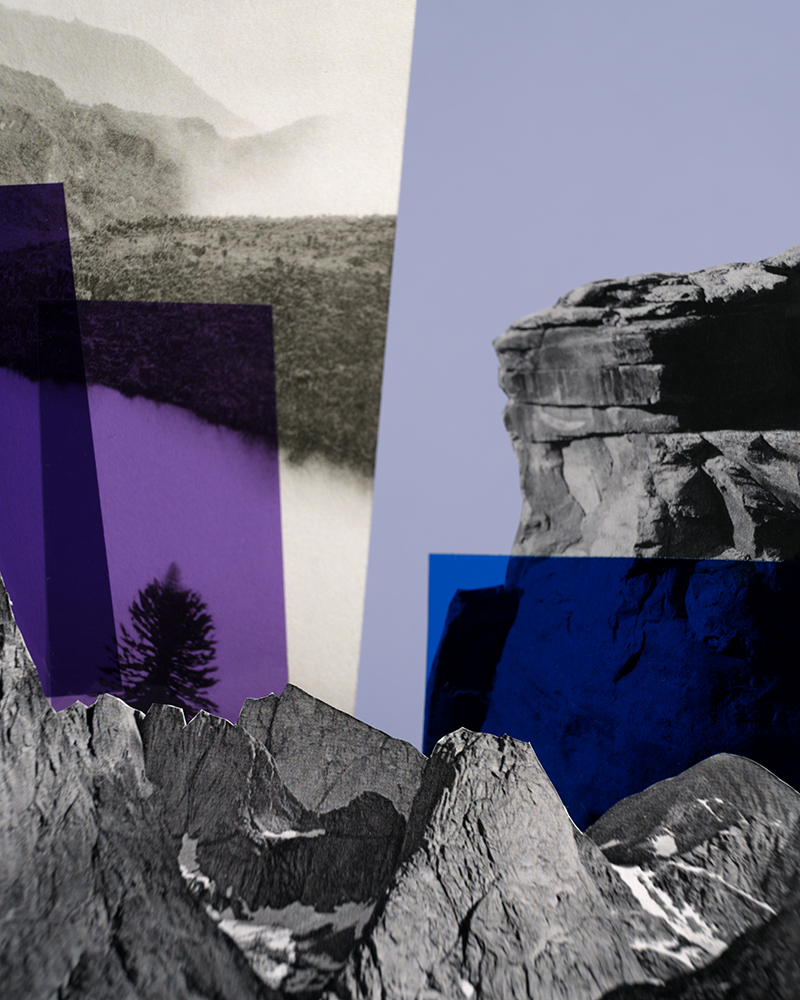

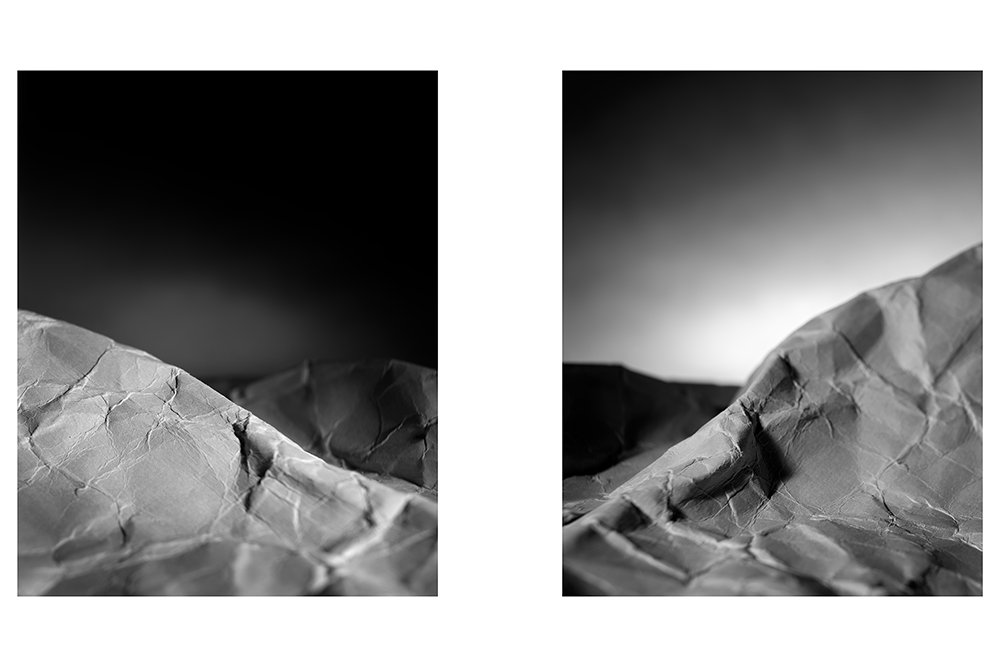

Alongside this performative work, I create photographs of artificial geographies, using small and large-scale sculptural forms to produce facsimiles of nature. The invented forms and compositions look at landscape not as a reproduction of physical reality but as a reflection of social fiction, built on desired control or subjugation. Through clear fictionality, the landscape is reoriented from innate structure to ideological construct, losing its neutrality and becoming an unstable image, wherein the photographic surface is not reliable.

Daniel George: Tell us about your artistic practice, and where your interests in performance, sculpture, photography, and video originate.

Anna Garner: I grew up around photography; my dad photographed nature as a hobby and frequently took me with him to national parks or to the beach while he worked. He shot a lot of slide film so there were frequent family nights sitting in front of a large projector looking at his images. Being around the medium from an early age, I had an immediate and innate interest in working with a camera. I got my first 35mm camera when I was 16, which I primarily used to take photos of bands or to do fashion shoots with friends. As an undergrad I began to study photography more seriously, focusing on building skills in the color darkroom and lighting studio.

From an early point in my studies and development, my work has centered on both the construction of sets in the studio and myself as the subject. Performing for the camera came out of two things: the fact that I was always available as a model/subject and my experience in dance which gave me a familiarity with performance. Later, I learned how to work with sculptural materials including wood, ceramics, and various mold-making techniques. For a period, my studio practice omitted photography in favor of solely producing video and sculpture. When I went back to image making these skills naturally integrated into ways I had already worked with photography. Whereas when I was younger, the constructions I made utilized only found materials, I began to focus on integrating the language and history of sculpture and a more developed understanding of material to build out spaces with more intention and control.

My interest in combining the modes of sculpture, performance, and photography is rooted in the way the camera changes the perception of physical space and the body. I focus on the way that framing, lighting, and positioning alters myself as the subject and the constructions I build. Through the element of performance, I attempt to reinsert time into a fixed image and to move the photo from passive to active.

DG: Aside from Protecting Popo, you remain the sole figure in your performances and images. Would you describe the significance of your focus on self?

AG: Working with myself as the performer/ subject has always felt like the most natural way to work. With my background in dance and athletics, I understand how to move and position my body and how to communicate through it. It is also easier for me to embody the presence I am looking for in the work than to guide someone else to do it. In the works titled, Protecting Popo, I feel very lucky that the other performer was very easy to work with and understood what I was doing. With that project I was nervous to work with someone else, because it was the first time I did it, but the relationship we built, and the physical trust needed to lift him became a huge part of the work.

There are also many actions and scenarios in my work that I would not want to ask someone else to do. Many of my sets are not physically stable for the ways I activate them and many of my performances for video put the body physically at risk. So, I would never want to ask someone else to do those things. I do feel it’s important for me to be a part of the work, but I don’t feel the desire to convey personal or emotive portraits of myself. Instead, I seek to express the overall physicality and position of my body, the way it changes or is changed by the physical space and the photographic image.

DG: I continue to be fascinated by your use of fabricated spaces. Rather than relying on existing places (arguably the default practice for those working with photography), you create your own. I feel that this effectively validates your intentions of reorienting landscape from “innate structure to ideological construct” while also questioning the reliability of the photograph. Could you talk more about your intentions here?

AG: Though the predisposition is to view an image through its indexical properties, the practice of a photograph as a construction rather than a capture has existed since the medium’s invention. I’m very interested in early practitioners, such as even Hippolyte Bayard who staged for the viewer exactly what they wanted them to see, fore fronting the camera as a tool of manipulation. The fact, or maybe the myth, of the photograph’s connection to reality, to a moment that was, has been employed to the service of producing agreed upon histories and truths backed by the physical evidence of images. My interest is to call attention to the non-neutrality of the photographic surface and its employment in ideological materializations of landscape; specifically, how land manifests as visual stands-ins for power and control, or re-imagined relationships to nature that were previously disconnected by extractive mentalities that have broken apart physical space by fractions of worth.

In my work, I do not seek to replicate something outside of me or something that was, instead I aim to testify to the impossibility of deciphering truth from fiction, seeing image making as a subjective endeavor that speaks more to the maker’s predeterminations than to any inherent quality of the subject. I feel there is more to be gained from an image when it is understood as a fabrication, as a manipulation of perception. Through formal spatial compositions, loosely based in both landscape and architecture genres of photography I investigate preconceptions of materiality and image-making and how it influences the perception of truth. I hope for my images to destabilize the photograph as evidence, and to present it as neither stable, static, nor truth-telling.

DG: You write that by manipulating the documentary capacity of the camera, you are presenting “contemplations on physical uncertainty and examine visual hierarchies within nature, gender, and architecture.” How would you say your work accomplishes this?

AG: I’ll use as an example my work titled, Just Below. In this video-performance I built an 8-foot-tall structure reminiscent of the monolithic and simplified architectural forms within minimalist sculpture. Halfway through the column I built a 3-inch plinth, made of plaster, which I stand on top of and slowly chip away until the platform breaks, and I lose my footing. In this action, a seemingly clean and sterile object, painted white with only straight lines and planes, is activated with tension and the possibility of physical risk and failure. The supposed neutrality of the formalist structure as well as the gendered conception of monolithic forms is physically altered and ruptured, perceived stability substituted for instability.

In a very different way, my images from the series, Composing Land, look at monolithic forms that naturally occur in the landscape, particularly in the American southwest. Abstracting these formations into flattened and simplified constructions they are rearranged and framed through photographic tools that emphasize production, such as backdrop papers and gelled lights. The representation of these forms is understood not as a straightforward reproduction but as a construction. Through performing with the abstracted structures, the gendered meaning associated with verticality can also be removed or reorientated.

DG: Your use of “unstable forms and materials”, as well as your various precarious performances, highlight (at least for me) the multitude of dilemmas we are facing at this point in history—regarding anything from environmental to societal concerns. I am curious about your point of view on how you feel your work functions within these conversations and events.

AG: This is a great question. I do feel my work speaks to the instability of the current moment. The precarity of the body can be seen as a reflection of physical vulnerability, which certainly the pandemic has put into view in devastating and painful ways. The destabilization of material structures in the work can also be seen to question current ideological and social structures; the movement and reorientation of space can be viewed as a metaphor to the urgent need of restructuring and/or simply eradicating systems of power. My practice looks at instability, the reshuffling of forms, the inability to fully trust or to fully rely on an outward physical reality. It thinks about the uncertainty of accepted structures and the possibility of rearrangement and reorientation. In this way, it embodies both deconstructive and reconstructive methods in which to understand the current moment.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026