Medium Festival of Photography: Jessica Uhler

Today, we are continuing to look at the work of artists whose work I discovered at this year’s Medium Festival of Photography. Up next, Jessica Uhler’s project, Liminal.

Jessica Uhler is a Seattle area artist working with photographic imagery and written word to express deeply personal experiences. She seeks to uncover poetic and spiritual meaning and resonance through creating images of the quotidian seen in a new light. Her work documents and reveals the transcendent in the ordinary, often exploring the life of the home. Her background as a poet contributed to the form of this project both in word and image.

Follow Jessica Uhler on Instagram: @jessuhler

Liminal

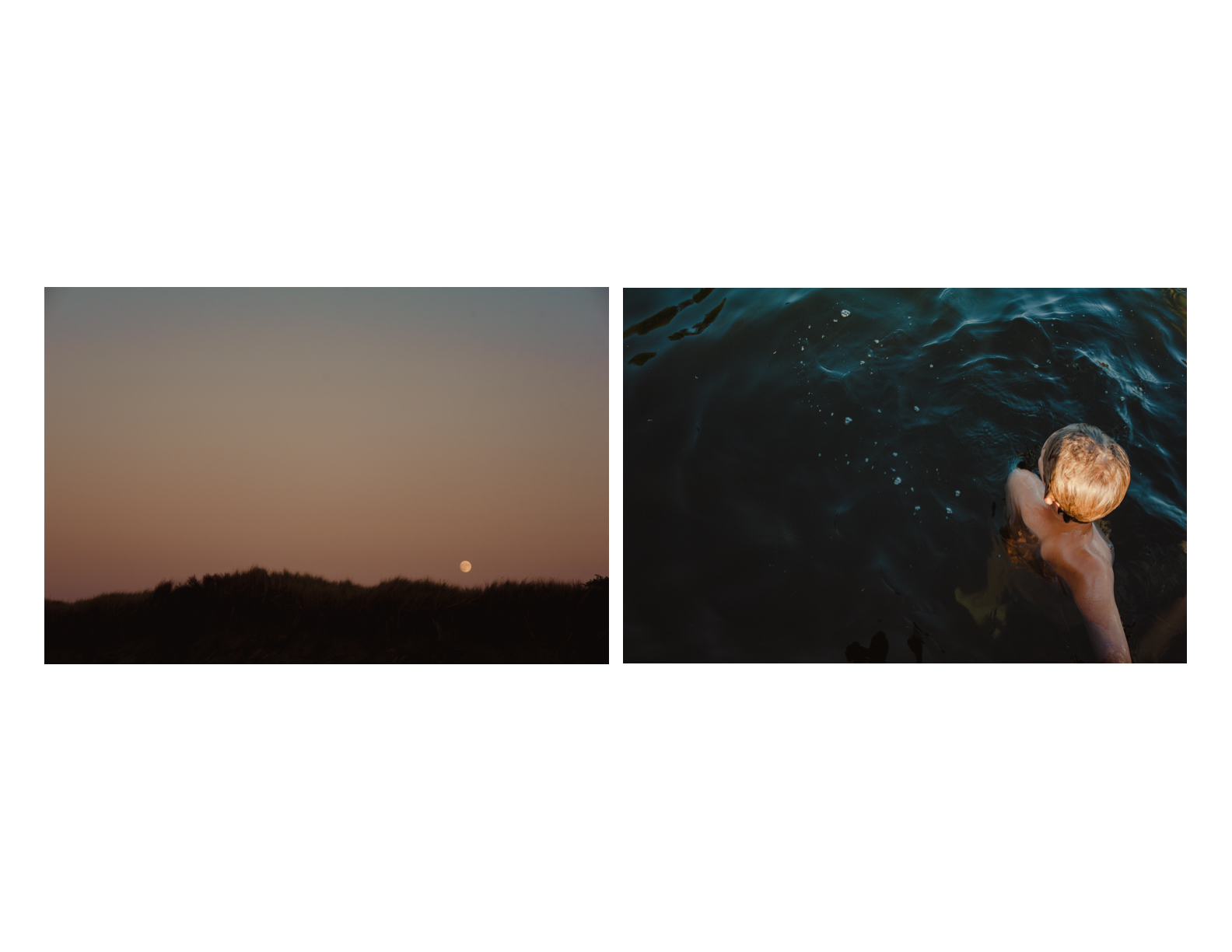

In this body of work, Liminal, Jessica gives voice to the experience of midlife identity shifts and the ambiguity of middles. It does not resolve, but engages the questions and dichotomies of liminal experiences. Motherhood subsumes many identities for women, and there comes a time of transition where we can reclaim and rename ourselves as our children get older. Using imagery of water and birth, this work is a way to process that journey through a season of becoming something new in parallel to her children maturing. Though personal in nature, the work speaks to very universal experiences of transformation through all liminal spaces, of being and becoming, crossing thresholds, and moving through the discomfort of ambiguity toward rediscovery and redefining, loss and hope. Referencing Jungian archetypes, it is a journey through life’s middle. Given the last couple years, this feeling and experience is one we share deeply. This diptych project includes a written and audio element as well.

Daniel George: With this body of work, you are considering your identity and relationship with your maturing children. I imagine that as they grew, you included them in your photographs, so when did you begin to notice something different—leading to the formation of this particular series of images?

Jessica Uhler: For many years- at least 15 or more, much of my energy, time and intention was focused on mothering, and managing and making our home. It was meaningful work, and naturally a lot of my creative energies and focus fell within that realm as I used my camera to find and celebrate beauty in the mundane. My children were often central in my photographs, but once all four of them were in school full-time I sensed the need to shift my gaze, which began with a lot of interior processing, introspection, and questioning. Of course, as they grew in autonomy and independence they were less readily available and willing to be photographed. These images coalesced as a way to communicate my interior landscape as I struggled with my shifting identity and role, particularly in motherhood, but also in all the ways that midlife invites us into a sort of reckoning. RIchard Rohr, and many other teachers, reference the two halves of life and how for the self-aware, open person, the second half of life is often a time of great questioning and reevaluation of your beliefs, your sense of self, and the containers you used to create an identity. It can be quite productive but also painful. I don’t think our culture honors the beautiful crucible that midlife can be, often reducing it instead to tired tropes and cliches.

DG: This project, along with others on your website, have an autobiographical component. Could you describe your interest in using photographs as means of investigating one’s psyche?

JU: I’m always interested in looking at and trying to make photographs that have layers of meaning, that say more than what is represented visually. The desire to use photographs to investigate my psyche became stronger the more life changed in our home. I’m not satisfied living an unexamined life. Motherhood is a very embodied experience and identity, and the physicality of it changes over time. It’s hard to put words to it exactly, but I had a strong urge and need to go deeper into myself and use photography to express the struggle of fully becoming my authentic self– finding new ways of being, and how complicated that can sometimes be in the context of marriage and motherhood (or any relationship). We become our truest selves in relation to others; we are made for community. Yet what I am trying to express through these images and words is the process of untangling, returning to a foundational sense of self that is integrated and whole, a solitude that can meet other solitudes, like Rilke says. I’ve always been interested in the idea of integrity and the root “Integer”- a thing complete in itself. But the experience of motherhood is often one full of divided selves and conflicting priorities and desires. Naming this process and trying to express it is a move toward wholeness and integration.

DG: You also regularly utilize text along with your image—amplifying your personal voice (literally, in the case of audio). In what ways do you feel that the written or spoken word augments your photographic work?

JU: My first creative language and practice was poetry (I have undergraduate degrees in Creative Writing and Philosophy), so the pairing of words and images has always felt natural for me because they come from the same stream creatively. WIth this project I felt a pull to create less representational work, and more images that resonated like poems. I never want one to explain the other, but rather to enhance and expand the understanding and experience of the work. The text creates context, a container from which to view the images. And the images themselves become poems in relation to each other. That is a key element in this project – juxtaposition and contrast – the way the images sing or bump up against each other. Sometimes there is a harmony between the images and sometimes conflict or dissonance- and that opens up new ideas or ways of seeing. In that way the form speaks to the subject; isn’t that what we do relationally? Sing and clash? The spoken word element in conjunction with the images creates a more immersive experience and invites the viewer into a journey, a story, and to find their own story within it. My personal voice reading the text is an intimate and vulnerable element. I hope that vulnerability lands in a safe place and helps break down internal walls and act as a catalyst for self-reflection.

DG: Tell us more about the use of diptychs—and the relationships you are creating as you expand and connect each frame with another.

JU: Perhaps a better word for these images is “conversations”. Diptychs tend to be images that only work in context of each other, where each has an element the other is missing. The images in this project feel whole to me on their own, but create new layers of meaning or interpretation when paired. They hopefully work the way language works in a poem, to surprise and arrest, spark something in the viewer, create a new space for the connection of disparate things. The process of trying images together side by side is exciting and playful for me. The sensation when a pairing works is very reminiscent of the experience of shooting a photograph you know you will like, or writing a poem that seems to come from outside yourself. I think together the images become metaphors and new landscapes of experience. They create a visual space that expresses ambiguous and hard to name feelings.

DG: Toward the end of your artist statement, you reference the collective experience of the current pandemic years and how your photographs connect with that theme of “crossing thresholds” and “journey through life’s middle.” Would you expand on this idea of utilizing art to process these redefining moments—perhaps in the context of this series?

JU: So much has been written about and studied on the psychological effects the uncertainty of the last few years has had on us. The sustained fear and simply not knowing what the next week, month, or year holds, not being able to plan or have concrete answers has been a liminal experience; a waiting room. The suspense and questions about what it looks like to move forward in a post-pandemic world, when that will happen, what has changed, and how we ourselves have changed are still in the air, in the collective consciousness. What have we shed and what have we gained? How has it been a metamorphic experience for all of us? All of these larger questions were layered upon my feeling of being unmoored as my children got older and more independent, of going through my own metamorphosis. Being unmoored allows for greater freedom and possibility, but also a restlessness and disorientation as you navigate new waters and away from a familiar harbor. We have a lot of language around adolescence, and even the empty-nest experience. But this transition I’m referencing is also a threshold. Maybe less visible and also a “middle”. Middles aren’t sexy or flashy. They don’t make for newsworthy stories. To begin a thing or complete a thing gets attention. “A long obedience in the same direction,” to quote Nietszche, is what actually builds a life, a family, a career, a marriage. It is a slow and hidden process. Expressing through art the conflicts and questions I felt as I navigate this stage of life is the best way I can start a conversation around it and give voice to an experience I know is a shared one.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026