Richard Koenig: See Change: A Memoir

See Change: A Memoir

Mapping mutations of a medium, and one of its disciples, over time

The transition from modernism to postmodernism, in the art world generally, occurred over a period of time. The change was initiated, perhaps, when Warhol and Rauschenberg began to use found imagery in their paintings in the early sixties. During the remainder of that explosive decade, and into the seventies, we saw the blossoming of minimalism, earth art, and performance, amongst other wonders. For whatever reason, fine art photography took a little longer to make the leap, to move out of the shadow of Edward Weston. Perhaps this was due to it being a medium which sprang from modernity itself—its products are created by a machine, rather than by hand.

In any case, I like to think art photography entered the postmodern realm around 1980, to give it a nice round number. In actuality, Barbara Kruger, Martha Rosler, Cindy Sherman, and Sherrie Levine had been disrupting the status quo for several years prior to that, and by the early eighties their artistic production was becoming quite notable, if not notorious. Artists championed appropriation, deconstruction, and use of text in questioning the tenets of modernism. In terms of landscape, that most venerable of artistic genres, we now know 1975 was a turning point as that was the year of the New Topographics exhibit, when Robert Adams would begin his slow-motion dethroning of Ansel Adams, no relation. Rather than uplift via unspoiled wilderness, these new works focused on the collision between nature and culture.

I had met Ansel, in the summer 1980, at his workshop in Yosemite; I was steeped in modernism, doing large format work while attending Indiana University, which was located in the town of my birth (figure 1). One year later, after working briefly with Jeffrey Wolin, who had just joined the faculty, I abruptly moved to New York. I was following a girlfriend, who would attend Barnard, while I transferred to Pratt Institute. The relationship didn’t last long, which is not a surprise in retrospect, but I’ll forever be thankful for it as I had been liberated from the hinterlands, injected, as it were, into a milieu that couldn’t be more different than what I was accustomed to. New York, a world city, was culturally and socially rich, ethnically diverse, visually stimulating, and more than anything else, steeped in history. I loved that I lived in the borough of Brooklyn, which had its own cachet, despite the relative hardness of the times.

While I suddenly found myself in one of the artistic capitals of the world, it didn’t necessarily mean that I could grasp, process, and put into practice what I was seeing go on around me, as habits can be difficult to break. I was shooting with large format and looking at the work of Minor White and Frederick Sommer, whose work was decades old at the time. I did change, however, after coming under the spell of Arthur Freed and Philip Perkis, both of whom taught at Pratt. I switched back to working with a small camera and began to emulate their looser approach. This meant eschewing previsualization and shooting unconsciously, more akin to taking a quick glance at something rather than staring it down (figure 2). Even still, as I look back now, I can’t say that I was much closer to a postmodern practice. I can see change, but there was no sea change.

~ ~ ~

There were other changes afoot. Upon graduation I transitioned, naturally enough, to the world of commercial photography in the city. After working for Roger Prigent, who did fashion on the Upper East Side, I settled in with John Manno, a creative still life photographer doing advertising work down in what we called the Photo District. His studio was half a block away from the historic Flatiron Building, from which the neighborhood now takes its name. With this kind of work, we often shot with 8” x 10” view cameras and powerful studio strobe units; before exposing film, we’d shoot huge Polaroids to show the art director and clients for their approval.

After a time, I moved from assistant to studio manager, and created my own “book” on the weekends (figure 3), but somehow, I could not make the jump to open my own studio. While I enjoyed commercial photography—it was stimulating, creative—it just wasn’t a passion. And little did I know, a change was coming that would utterly disrupt this industry.

During this period, a decade since graduating from Pratt, I would go home to Indiana periodically to see my parents and have lunch with Jeffrey Wolin, with whom I was still in contact. In the time since I had first worked with him at IU, he had been promoted and built the photography program into something special. Eventually, it hit me that I should emulate Wolin: go back to Indiana, get an MFA, and teach photography at the college level. I would depart New York in the summer of 1995 for this reason—I recall that I signed the final check for my undergraduate debt, and then immediately turned and signed a promissory note for graduate school loans, which would be an obligation on a whole new level.

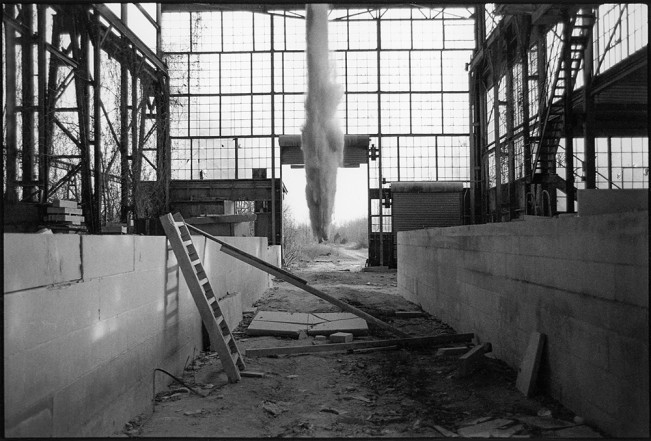

Once back in Bloomington, I was free to experiment, follow my whims. I wanted to make work of the time and attempted to embrace a postmodern approach. Looking back now, however, it seems that I was mucking around in what might be called neo-modernism. I settled on medium format for this stage of my creative life, thinking that it was the best of both worlds—compact and portable, but with good resolution when using a quality lens. After getting lost for a time shooting specimens from the biology department, I settled in on a defunct limestone mill in town (figure 4, frontispiece). I grew up listening to strange sounds emulate from a limestone quarry nearby, so it seemed natural to explore this endemic industry.

~ ~ ~

Not long after art photography attained postmodern status in my mind, a truly paradigmatic change took place: the analog to digital revolution. This began in the mid-1980s and would gather speed for a decade. Those with deep pockets—the film industry, commercial advertising—would be the first to take the plunge. In terms of vernacular photography, I recall reading that the sheer amount of film being consumed by the public would cause the transition to digital to happen slowly, but when it really kicked in, it was a juggernaut. I was, once again, slow to change with the times. I even stuck with black & white rather than move to color while I was in graduate school, crafting split-toned fiber-based works when most were making C-prints. Eventually I made the move, to pixels as well as to color, simultaneously, right around the turn of the 21st century.

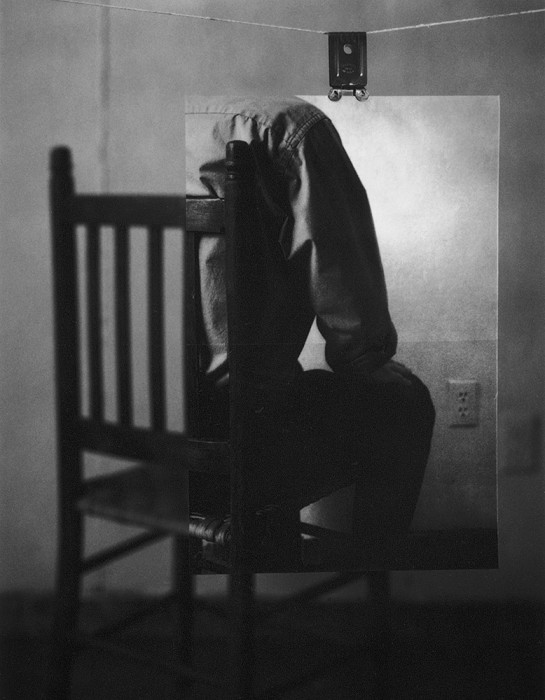

After bagging my MFA, I began teaching at Kalamazoo College. Initially I struggled to find content, but eventually began to re-photograph my own images (figure 5) à la Kenneth Josephson.

I tended to focus on the banal for these pieces as I saw photography itself to be the subject. At a residency in 2001, I turned the camera on myself for a small series called Koans (figure 6).

Soon after, I became intrigued by the work of a Dutch conceptual artist, Jan Dibbets. He made some simple photo-based pieces that illustrated the idea of anamorphism, which privileges an exact point-of-view. Eventually I combined this concept with re-photography to create something that I felt was new (which is another holdover from modernism—the quest for originality). I called these works Photographic Prevarications, as I wanted to play up the medium’s ability to tell untruths, albeit in a believable fashion (figure 7).

For this series, I would take a digital photograph, distort the file in Photoshop based on the principle of anamorphism, make a large-scale print from that altered image, and finally install it in situ to be re-photographed. This is probably the closest I got to authoring postmodern images.

I made pieces in this manner for quite some time but eventually began to grow tired of the procedure, which can be rather tedious. I had the urge to go into the field and simply “take pictures” once again. Beginning in 2010 this took the form of a long-term project to document the original route of the first transcontinental railroad between Omaha, Nebraska, and Sacramento, California. I had stumbled onto the story of the building of the line and was hooked. With this work I wanted to evoke the memory of the immigrant workers who built the railroad with their hands in the 1860s: Chinese for the Central Pacific (figure 8), and Irish for the Union Pacific. I was mindful of Native Americans, whose way of life would be irrevocably harmed by the intrusion. During the course of this project, with its focus on history, another change occurred: I began writing and publishing articles rather than exhibiting.

~ ~ ~

In the end, Geoffrey Batchen, by way of Steven Bull (Photography, Routledge, 2010), tells us there is a middle path between modernism’s focus on the nature of the medium and postmodernism’s concern with the changing cultural context in which photography finds itself. After being trained in the first mode, and then spending a significant time of my life attempting to work my way into the second, I’m now happy to settle back and take this middle path. In this era of post-postmodernism, it’s not either/or, but both/and.

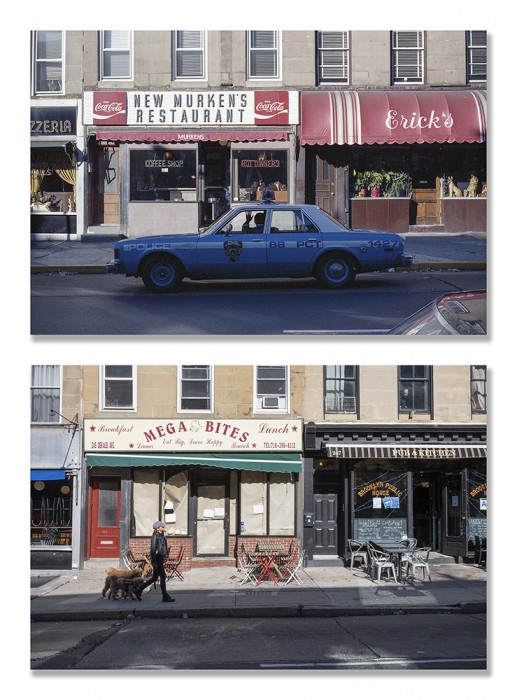

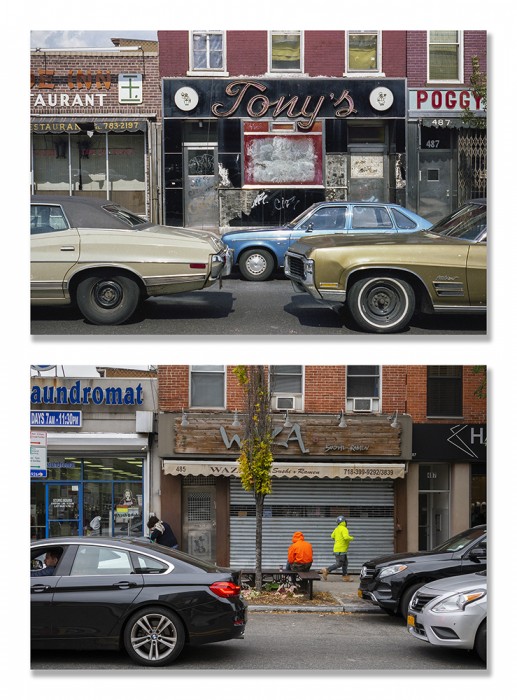

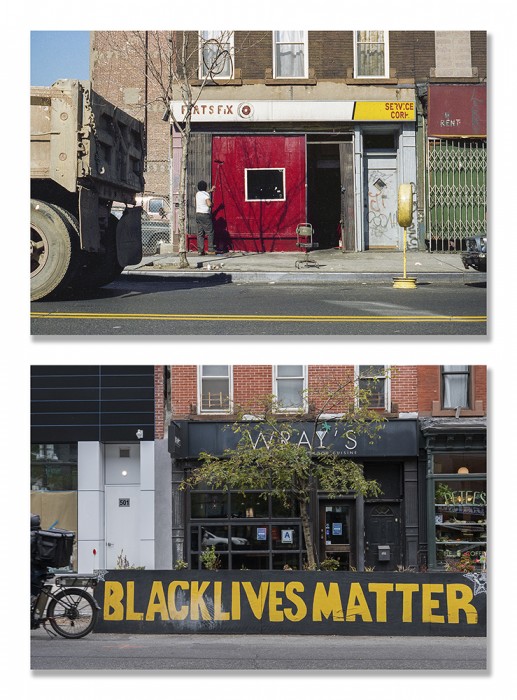

One of my professors once told me that self-portraits are always a good exercise for a photographic artist. Likewise, I think reviewing one’s work from the past can be fruitful. The pandemic of 2020 provided time for retrospection—as well as for the scanning of old negatives. This led to my current project, City as Metaphor, which has me, once again, walking the streets of the city, mostly Brooklyn (figures 9-16).

When I first arrived in New York forty years ago, I would explore the area around Pratt Institute, practicing my own tentative form of street photography, like the frightened kid off the pumpkin truck I was. Now, using satellite technology, I enjoy tracking down my previous peregrinations, to the exact street address. After making small prints for easy viewing in the field, I trek back to the very spot and frame the scene to emulate the historical image. While I attempt to replicate the exact same point of view, I can’t help but to see change.

City as Metaphor

With this project I revisit locales in New York City (primarily Brooklyn), where I made photographs several decades ago. A contemporary, high-resolution image is then made, framed to mimic the prior photograph. The updated view is then combined with the vintage analog work to form a straightforward diptych à la Mark Klett’s Rephotographic Survey Project of the late seventies.

The goal of this undertaking is to allow the viewer to study how visible things may have changed over a relatively long period of time—the most notable being, perhaps, an explosion of trees and foliage. But while the image-duos describe this and other changes based on physical appearances, it is hoped that a reflection of a deeper sort may be elicited. One may ponder what has transpired generally since the vintage views were made—the nature of the photography exhibited here is a receipt for a far-reaching digital revolution still unfolding. Beyond image and information technology, though, lurk other truly impactful events, some of which can be discerned from the images, while others cannot.

The circumstance for having created the vintage images (while the author was studying photography at Pratt Institute in the early eighties) is arbitrary, but not insignificant. While not as dramatic as the shift in social, political, and cultural mores that occurred in the late sixties, the author, like many others, feels 1980 marks the beginning of a shift toward a new gilded age in the United States.

Citing the oft-stated fable of frogs slowly being cooked alive, we tend not to notice incremental change, even when dangerous or possibly fatal in nature. It is hoped that the simple tactic of using time-comparison photographs will work to jar the viewer.

Born in 1960, Richard Koenig received his BFA from Pratt Institute. In 1998 he received his MFA from Indiana University and began teaching art and photography courses at Kalamazoo College, Michigan.

His fine art work, Photographic Prevarications, was shown in six one-person exhibits in as many years (from 2007 to 2012). Koenig’s long-term documentary project Contemporary Views Along the First Transcontinental Railroad spawned four articles (between 2014 and 2019). In addition, he published a memoir piece, “Growing Up in a Railroad Vacuum” in Railroad Heritage (in 2017), as well as one on New Mexico’s last active semaphores in Railroad History (in 2019).

In 2020 Koenig collaborated on a project called Hoosier Lifelines: Environmental and Social Change Along the Monon (1847-2020). A journal article on the history of railroads in Traverse City, Michigan, was published in 2021 (in the Double A) as well as an article on the end of street-running.

Follow Richard on Instagram: @richardkoenig6644

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: The Photobooth Technicians ProjectNovember 11th, 2025