Contemporary Approaches in Historical Processes: Kasia Kalua Kryńska

How does modern alternative process differ from traditional uses of historical process? This week, all of the artists that we are featuring use historical processes with very contemporary approaches. Some of the artists alter the chemistry. Others combine their chosen process with other techniques, not only breaking the rules but opening up more possibilities to define contemporary alternative process.

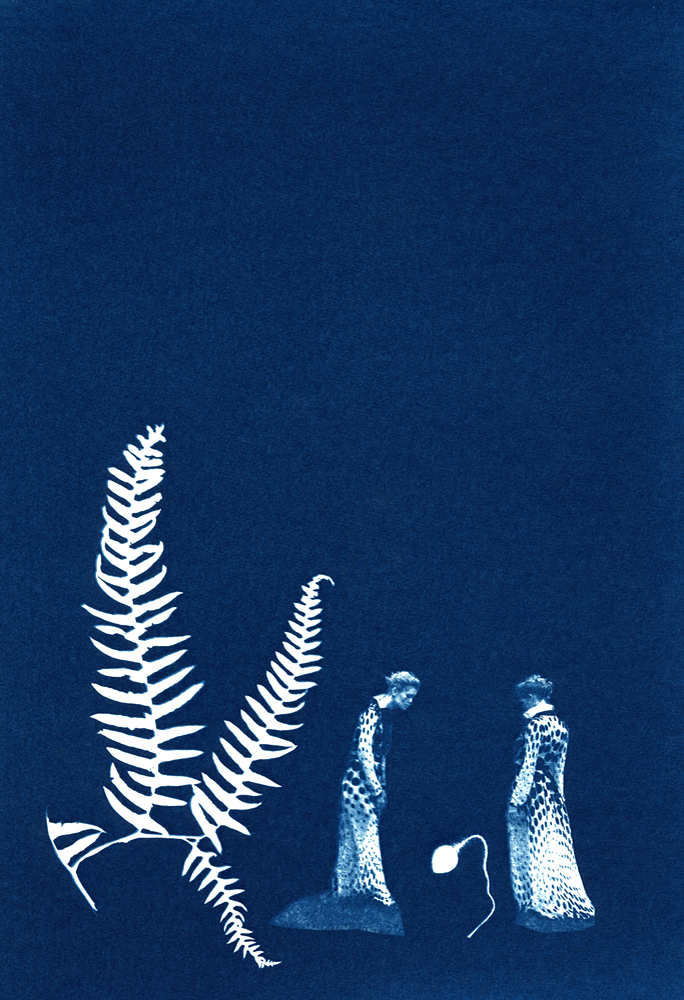

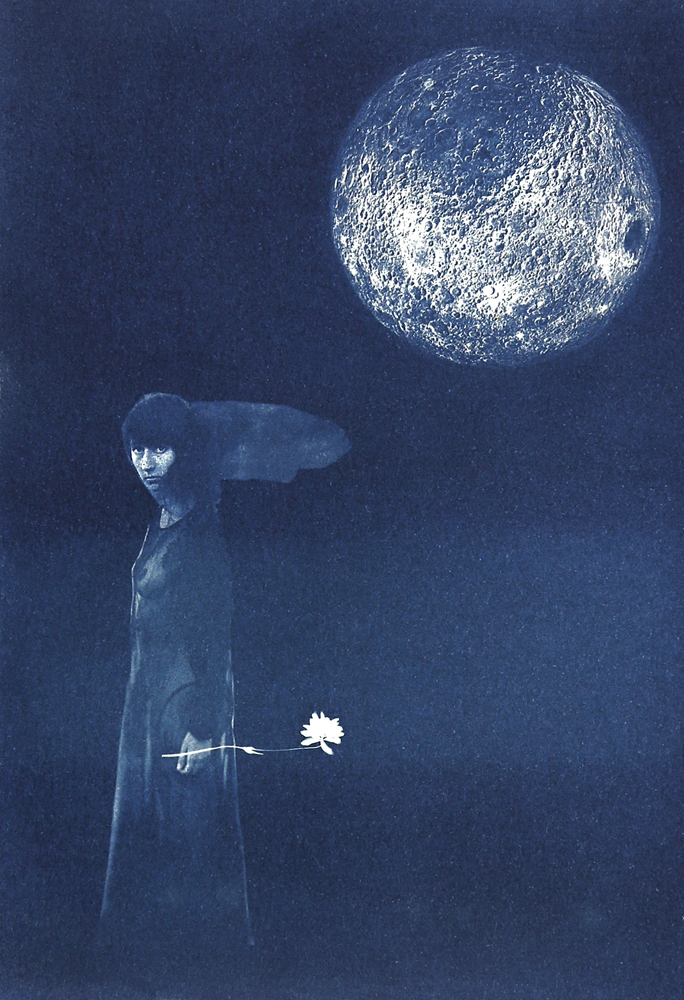

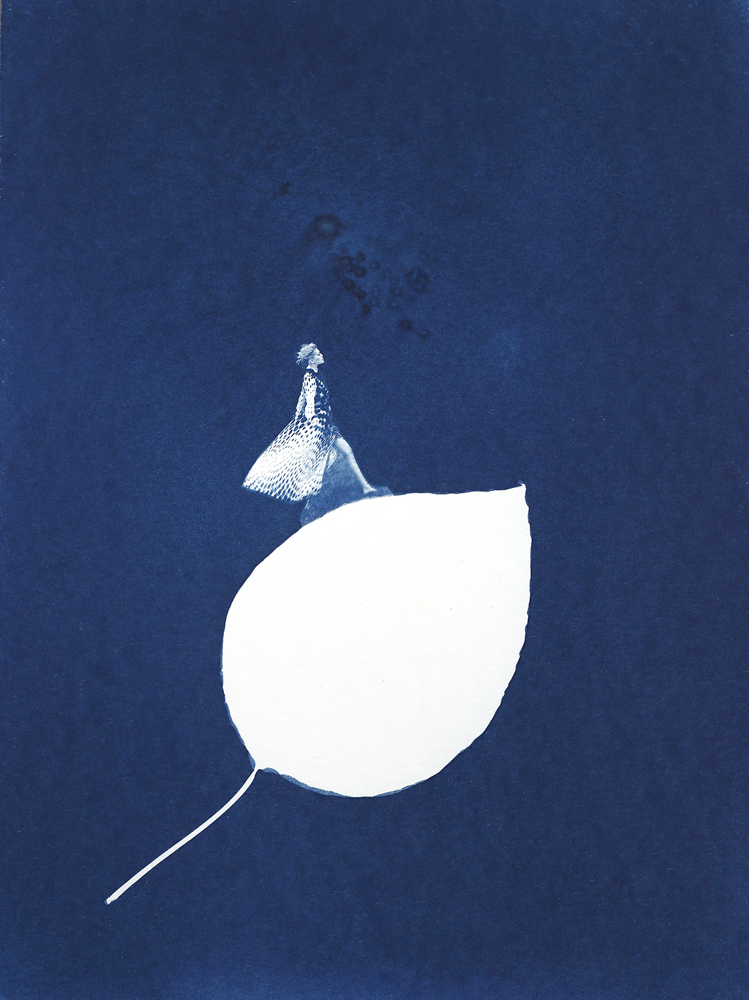

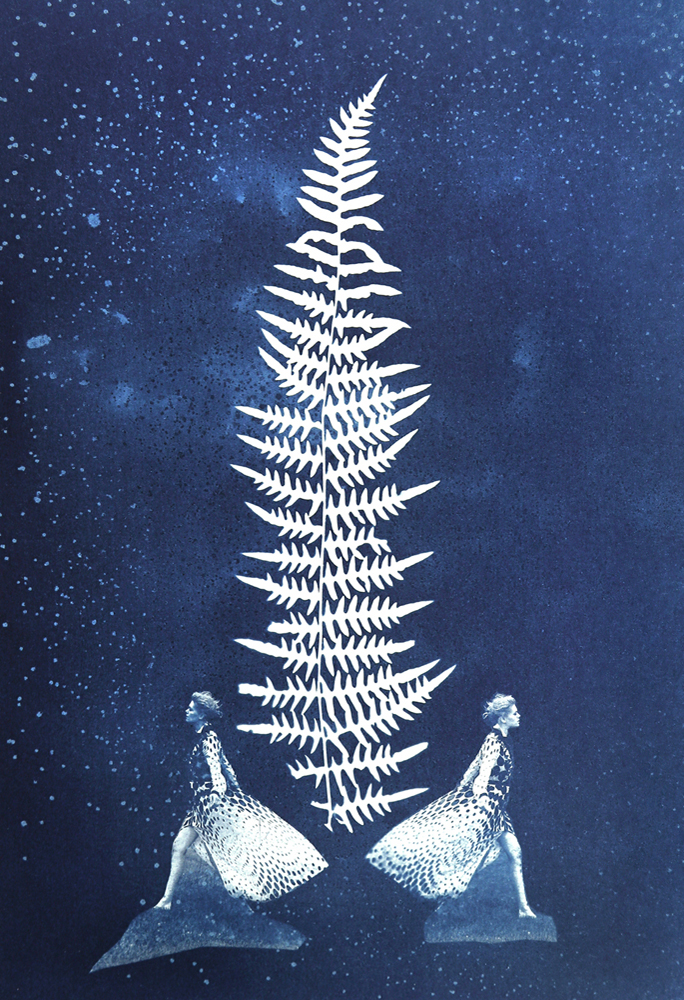

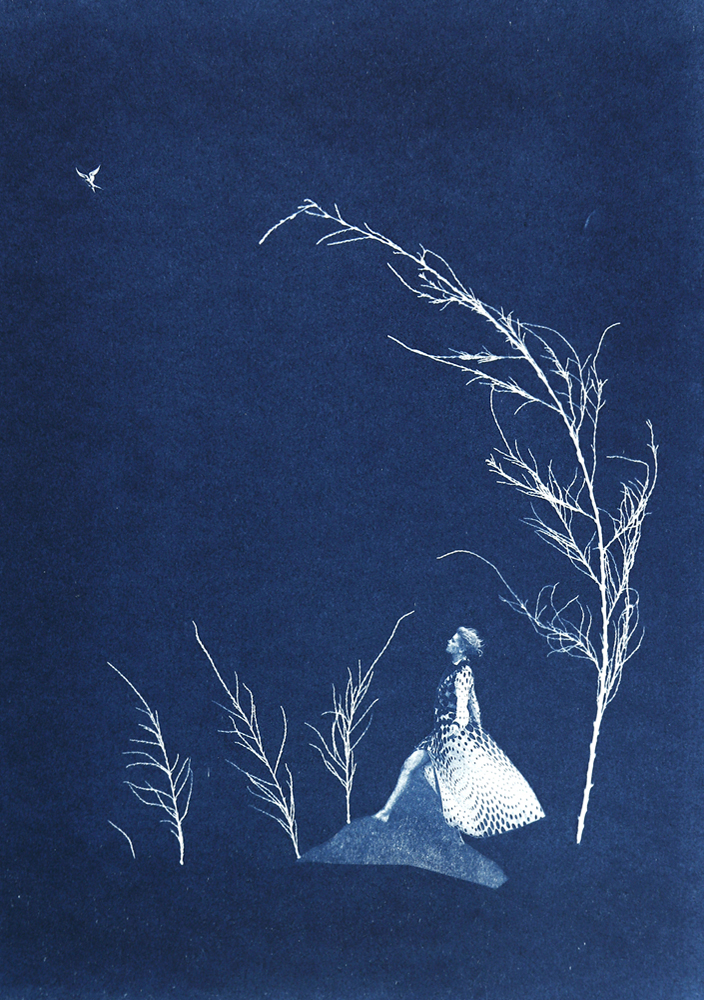

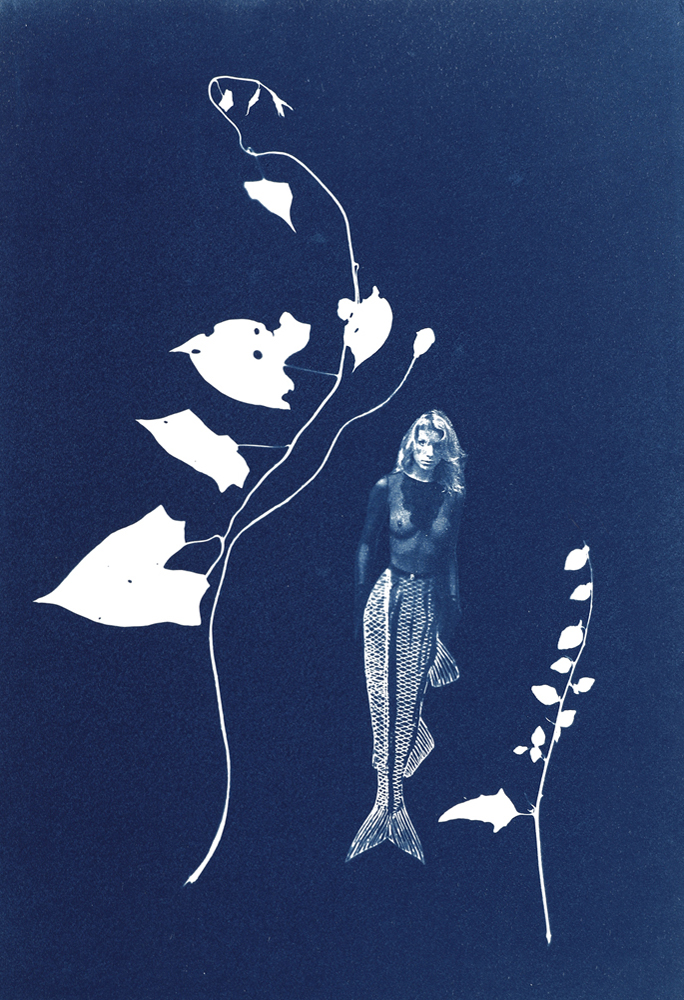

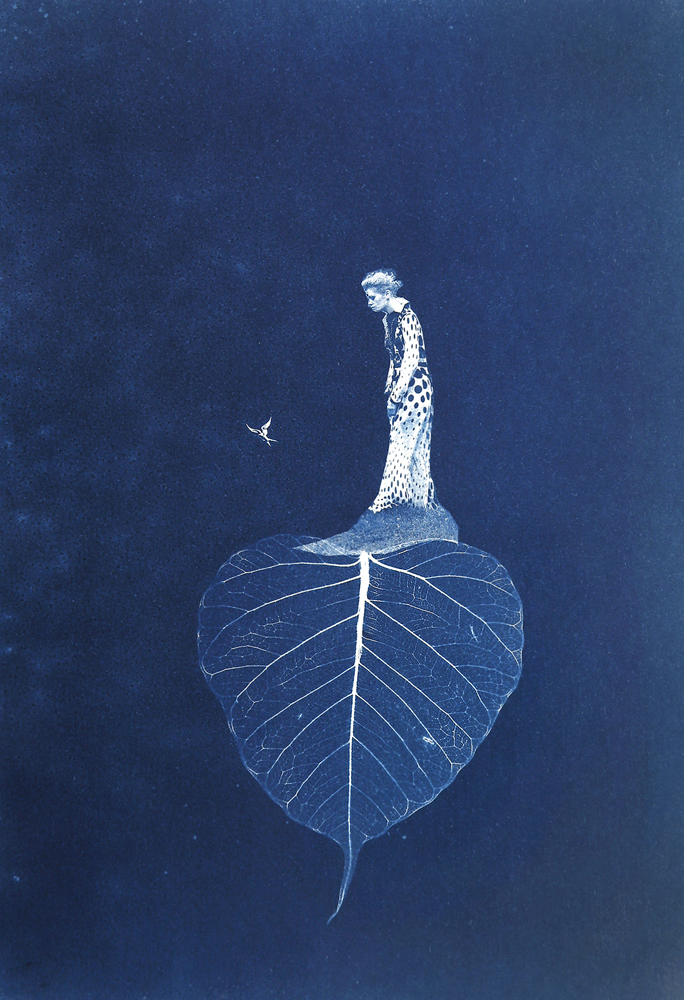

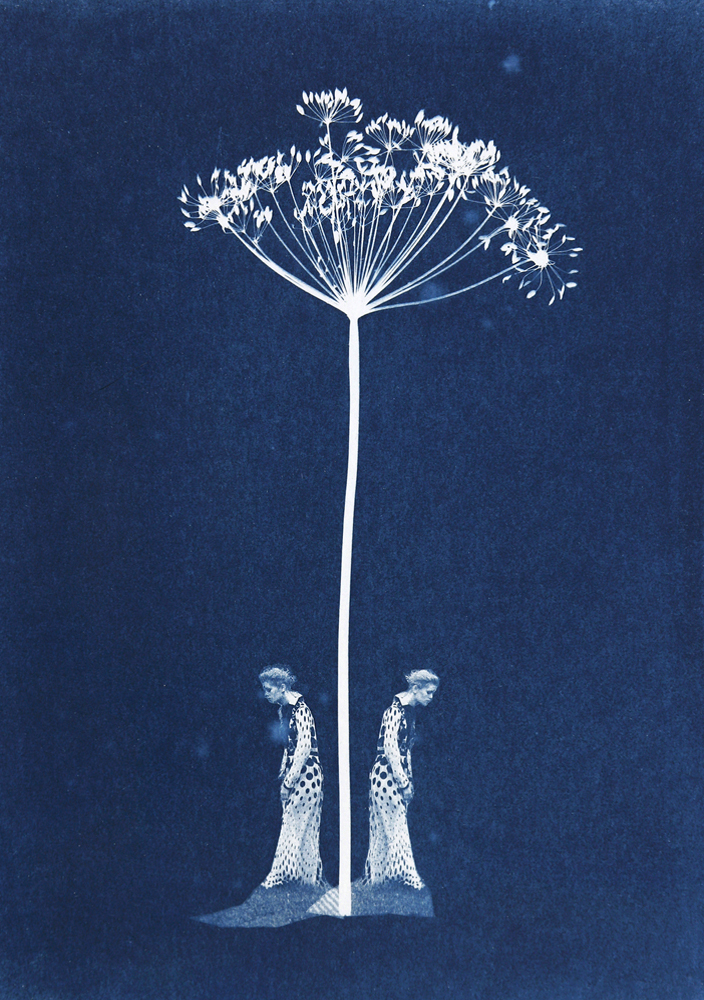

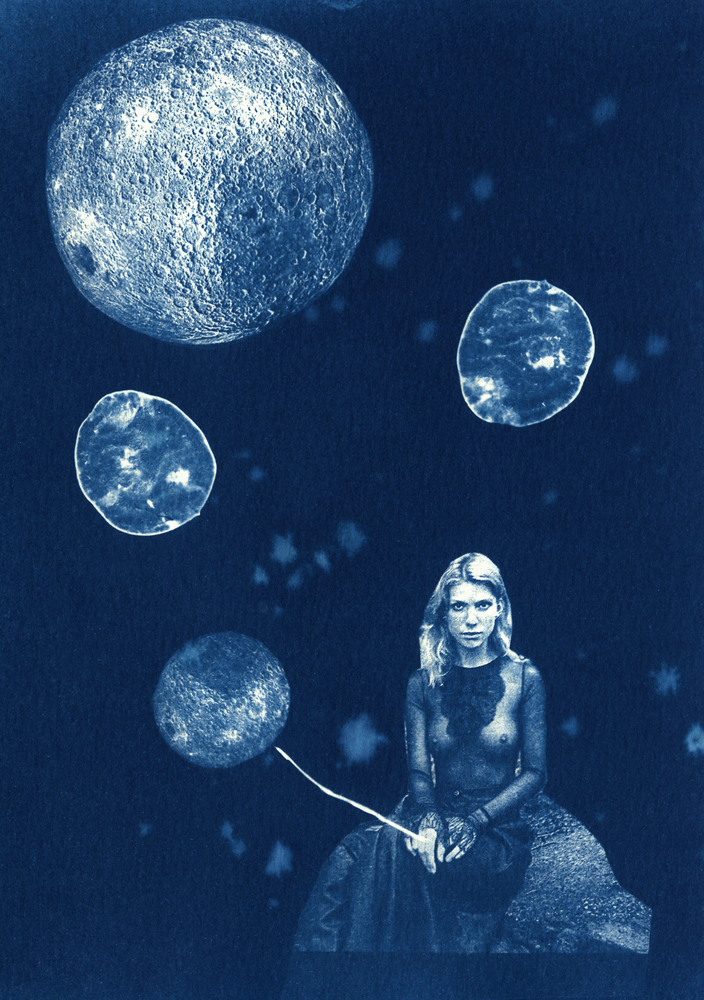

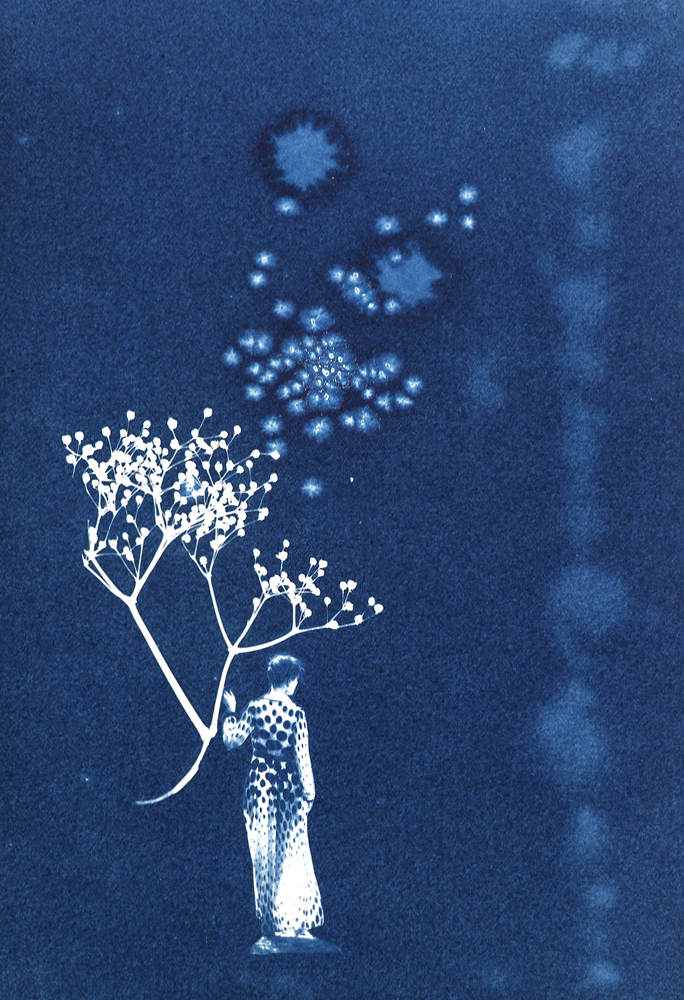

Kasia Kalua Kryńska’s book and series Blue Moon Garden interest me for a lot of reasons. The pandemic led the Polish artist to make work that feels really optimistic considering that most of the world was in seclusion in 2020. I would even argue that much of the work being made by other artists felt like the world was ending. The natural world provided Kasia with an escape; she collects plants and prints her unique cyanotypes in the sun. She then makes collages with negatives and photograms from plant impressions that harken back to Anna Atkins’s Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. The marriage of the two processes creates a magical world from the imagination of the artist, allowing her psychological freedom, though temporary, from life during COVID.

Kasia Kalua Kryńska (Warsaw, Poland) is Architect, designer and photographer. PhD in photography. Belongs to the Association of Polish Artists Photographers (ZPAF). Lecturer in photography. Jury member at Vintage Photo Festival. Her photographs have been shown in numerous individual and collective exhibitions in Poland, Ireland, Portugal, Holland, Germany, Spain and US and are held in private collections.

She specialises in emotional photography, portraits and fine art photography, using traditional and alternative photography, works with photosensitive materials. She experiments with a variety of 19th century photographic processes like Wet Plate Collodion, Van Dyke, Salted Paper and Cyanotype. Author of the BLUE MOON GARDEN album. Winner of the Black & White Spider Awards, the International Color Award and Photos de Femmes. She won first place in the Wet Plate Competition Canada and the Grand Prix at the Vintage Photo Festival, Blue Moon Garden cyanotype series was awarded in the Julia Margaret Cameron Awards and presented at the analogNOW! Festival, Foto Art Festival, Month of Photography Bratislava and Biennial of Fine Art and Documentary Photography in Barcelona. Her photographs have been featured in many publications, including SHOTS Magazine, SOURA Magazine, BLOW Photo Magazine, PRISM Photo Magazine, SEITIES, The Hand Magazine, FotoNostrum Magazine, Photo Trouvée Magazine and others.

Follow Kasia Kalua Kryńska on Instagram: @kasia.kalua.krynska

I am a supporter of emotional photography. I strongly believe in the therapeutic role of art and I consider the creation process to be very important. It allows you to intuitively navigate through unknown space to allow yourself to reflect and reach your own borders. Borderland issues interest me the most. What happens at the junction between matter and spirit gives meaning to my work. Analog photography is my medium, where film filtered through experience becomes a nonobjective and multi-dimensional record. There is room for surprise, chance and imperfection. I don’t strive to perfection in my work. In the aesthetics of error I find new meanings and that stimulate the imagination. Using alternative techniques, including wet plate collodion, pinhole or cyanotype I become more of an alchemist and poet describing a fleeting impression rather than a reporter recording the real world.

Greg Banks: Tell us a little bit about your childhood and how you became photographer?

Kasia Kalua Kryńska: Photography has always accompanied me. I made my first steps in the darkroom under the watchful eye of my Dad. In a small bathroom, there was an enlarger on the washing machine, and litter boxes were spread all over the tub. The image that appeared on a piece of paper made such a strong impression on me that I am still seduced by the magic of photography. The smell of chemicals, red light and the procedures to be followed soon fascinated me, and the darkroom became my favorite place to spend my free time. Already in primary school, I made 30 copies of a given shot for my classmates.

I loved to experiment, I used to paint in the dark to reflect the twilight mood, the results were sometimes slim. I became more familiar with the possibilities of film, the construction of the camera, the use of long times that allowed me to realize my intentions. It was a process, the knowledge came with time.

GB: You are a designer and architect as well as a photographer. Talk about that influence in your work. I think I see it in several of your series which feel more formal like Flat Calm and even 13 squared.

KK: During my architectural studies I learned about the canons of beauty, proportions, the principles of perspective and rhythm, which I soon began to consciously apply in photography, as well as experiment with them. Photography and architecture were intertwined. I was fascinated by the detail, light and depth of field. I needed more time to make a sketch and the conditions were not always favorable. So the small camera soon became my best companion. It was through photography that I was able to combine different fields of art and became a keen observer.

During my photography studies, I had the opportunity to learn about different styles, different perspectives and sensibilities. It quickly became apparent that my interests did not follow the obvious, patterns and correctness. In contrast to the orderly world of architecture, photography increasingly liked to get out of hand. Instead of symmetry and geometry, I began to be fascinated by human beings and all their emotions. The possibilities of the 35mm films were quickly exhausted, and the period of fascination with medium format came. In the 6×6 cm frame I found my world. The beloved Rolleiflex became not only my best friend, but an integral part of seeing, thinking and feeling. It was then that the awareness of photography came. Emotion, message and mood building became a priority. The form always had to be consistent with the image.

GB: How and why did you become interested in alternative or historic process?

KK: The interest in alternative photography came with the need to go beyond the frame. It was a process that stemmed from an integral need to experience and perceive more than reality. I first reached for expired light-sensitive materials, extended exposure times, and made the real world a bit more ambiguous using a pinhole camera. My need to observe the outside world was transforming into a need for an insight into the inner world. As the techniques changed, the subjects of my works and the questions I asked myself changed. The creative process itself became as important as the final result.

Using the 19th century photographic techniques, I became more of a subjective poet describing emotions than a reporter recording reality. The creative process, which required more concentration, began to appear as an engaging novel in which the plot unfolds slowly and the ending is sometimes surprising. Than, a subjective, unique image most fully reflects the complexity of borderline phenomena and problems, where reality confronts the unconscious. In the aesthetics of error, I find new symbolic content that stimulates the imagination, prompts reflection. Spontaneous creation, techniques beyond my control can be found at the interface of matter and spirit, and this gives meaning to my work.

GB: Discuss how the longing to get outside during the pandemic led to Blue Moon Garden?

KK: The situation we found ourselves in at the beginning of 2020 was a time of trial that we were confronted with in various ways. In my case, this difficult period resulted in a strong longing for open space and contact with nature. Blue Moon Garden has become a land where imagination, longing and experience meet. The choice of cyanotype was not accidental. I found consistency in this technique with topics that require a certain kind of thoughtfulness.

The project touches on the essence of man’s bond with nature. The Blue Moon is the term used in astronomy for the very rare second full moon in a month. It symbolizes the moment of summing up and materializing what has developed over the past months. Blue also embodies melancholy as we become more and more lonely, detached from reality that changes much faster than our beliefs and habits. Perhaps we will find the antidote in ourselves as soon as we allow a balance between the expansion of the external world and the silence of the inner world.

GB: One of the things I love about the series is the combination of photographic imagery with the contact prints of the plants. What led you in this direction? And tell us more about your process.

KK: The limitations we faced every day during lockdown also influenced what, how and why I create. The seclusion was a time of reflection and an opportunity to look again into my archives of negatives. I created collages full of allegories from negatives and prints of plants I found. My own photos became a new source of inspiration for me.

In cyanotype technique, a unique monochrome image in the color of Prussian blue is createdmanually, directly on the paper which is coated with a photosensitive substance. Originally, I lit theworks in my studio under a special lamp which imitates daylight. As soon as the restrictions were eased down, I started to expose my works directly to the sun. It is the sun that gives them the depth of color.

Leaving the darkroom was symbolic for me. The days in isolation passed differently. Their pace was marked by dusk for preparations in the darkroom and a days full of creative work in the sunshine. My perception has also changed. Nature that was freed from human influence seemed to breathe, gain strength and be more lush, fuller than ever before. Every leaf, blade of grass, every new bud screamed – look how beautiful I am, how important and how special!

GB: There is something about your cyanotype work that feels different than your other work. More conceptual, and even more emotional. What led you to this transition from interesting portrait and landscape work to imagery that is more abstract?

KK: Cyanotype, one of the simplest alternative techniques, came to me unexpectedly as a need to break away from the complicated and demanding technique of wet collodion. I worked on it for several years, implementing an extensive series of Between Two Moons portraits and my PhD thesis Archetype Women. A Case Study at the Academy of Fine Arts. I was travelling with collodion and a self-constructed portable darkroom around Poland and Ireland, following the traces of ancient cultures and places of power. While looking for the possibility of making prints, I was interested in albumin, salt paper, van dyke and cyanotype.

Initially, I took the cyanotype with a pinch of salt. I had to tame it and find a personal connection with this medium. However, the lightness and freedom of creation brought me a lot of joy. I discovered it, played with it, and to this day it surprises me with the multitude of possibilities. The fact that the implementation of new projects does not require a camera, complicated chemical formulas or a photographic darkroom, and that the image appears directly on paper, revealed a different perspective on photography. Space emerged from the darkness and sunlight filled the darkroom. All it took was imagination. Lack of limitations became crucial. This prompted me to reach for collage, where, thanks to cyanotype, personal emotional topics created space of memories, an ocean of memory, a zone of searching for my own identity, family ties and bonds with nature. The cyanotype allowed me to do my work not only on paper. I reached for fabric, wood, I combined various media. In a personal journey into the past of women from my family in the Silence of the Heart series, many found a universal message, and the works won the Grand Prix at the Vintage Photo Festival, which was an important moment for me. In the land filled with allegory of the Blue Moon Garden created during the pandemic, I refer to the longing for paradise lost. I continue the theme of human contact with nature in the Biophilia series, where a picture of wood merges with a female figure, and on the fabric in Twilight I talk about the condition of modern man and the fragile contact with our own nature.

In each of these topics, the choice of technique was not accidental. Each print is unique, created by hand, with no rush. I find in them an intuitive freedom of creation. There is room for mistakes, but also plenty of room for experimenting and developing my own style.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026