South Korea Week: Ahn Jun: On Gravity

“Two forces rule the universe- light and gravity.”-Simon Weil, from Gravity and Grace (La pesanteur et la grace) (1947)

I Gravitate towards a particular type of photography.

I like photographs that are not easily readable, that stimulate my curiosity. These photographs give me a chance to let my imagination run wild. Such photos consist of many layers.

Click! What might have happened to the space the moment the shutter closed?

A process of empathy is needed between the photograph, the artist, and myself. To reach ’empathy’, I think perfectly from the photographer’s and artist’s point of view.

I remember being moved by an interview with the French novelist Bernard Werber. According to his expression, when the existence of ‘I’ is emptied, the ‘emptiness’ is filled with external energy. He explains that the ability to communicate with the world arises when the existence of ‘I’ is expanded to a non-constrained existence without limiting it to a certain frame, i.e., nationality, occupation, age, gender, etc. That realm is called the realm of curiosity.

As Werber argued, I believe that art plays the role of a medium in emptying the existence of ‘I’ and communicating with the world through curiosity and unimaginable imagination. In particular, photography stimulates infinite curiosity and imagination. As Werber said, it is about putting yourself into the position of others in order to reach empathy. To understand trees, imagine how they perceive light and how they feel the soil and moisture of the ground.

Ahn Jun, a Korean female photographer introduced this time, has already gained worldwide attention for her <Self Portrait> series. Her pictures are not edited by Photoshop at all. Her works lead to a dizzying experience at the boundary between reality and fantasy. The image of the artist herself hanging from the window sill of a high-rise building or perched on the edge of the roof railing is a reality. The artist looked down on herself from the roof of her 32-story apartment to overcome her fear of heights. At the moment, the artist sees the boundary between death and life. She photographed the gap between reality and fantasy. Her <Self Portraits> seems to have predicted her <On Gravity> series, which are introduced this time.

I imagine that Ahn Jun’s photos do not capture the moment of clicking. The reality in the photo is that it is permanently floating in a zero gravity space. It seems to be talking about eternity, not moment.

In this project with the theme of women’s lives, Ahn Jun’s works begin with a more fundamental human question. Along with the weight of women’s life, they are also pondering about it from men’s point of view. In the end, they ask you to imagine the time thrown into each individual’s life. From a cosmic point of view, they raise curiosity such as ‘how big is the difference between the time an apple falls on the ground and the time given to us’? The difference between human time until death and the time the thrown apple falls to the ground may not be much different from a cosmic perspective. What does the force of gravity mean? In Ahn Jun’s On Gravity series, I imagine that the apple could be the artist herself or her image.

Ahn Jun is a South Korean photographer based in Seoul. She has been trying to investigate hidden beauty of the world beyond our perception. Throughout several project-based works, she tries to reveal the hidden structure of the world cannot be seen since it moves too fast in the world of the context.

She got BA in art history in University of Southern California. She was introduced photography during her senior year of undergraduate study, and then got MFA in photography from Parsons. After back to Seoul from New York, she got ph. D in Photography on 2017 in Hongik University in Korea, with her thesis entitled The Aesthetic of Paradox in High Speed Photography.

British Journal of Photography selected her as one of twenty Photographers to Watch on 2013, and South China Morning Post selected her one of five Asian Artist to Watch in same year. Her works are exhibited worldwide including Triennial of Photography Hamburg, Daegu Photography Biennale, Shrine Kunsthalle, and Aperture Gallery. She published two photobooks on 2018, Self-Portriat(2008-2013) by Kyoto based publishing company AKAAKA, One Life by Tokyo based publishing CASE, both in Japan. One of her work from One Life is selected as one of JP Morgan Curators’ Highlight 2019 in Paris Photo. In 2021, she selected as one of female photographers by Elle x Paris Photo, initiated with Ministry of Culture (France).

Follow Ahn Jun on Instagram: @junahn922

“Photography is a painting of light. Gravity proves that one is alive. Grace is the spiritual reciprocity bestowed by a cosmic being. Ahn Jun captures the reality (gravity) of ‘life’ living in the physical world and the moment that exceeds the life (grace) with a picture of light (photography). The moment presented by Ahn is the time that is in life but exceeds life. Her light paintings show us a time when reality and fantasy overlap.”

Life’s Simultaneity

Ahn Jun’s work comes from life. “The day I first thought about death,” “The day when I [the artist] said I don’t want to grow up any more,” she said, “I hope all of my family remain unchanged.” (artist’s note) Her childhood memories and desires seem to have been the starting point of the series One Life and Liberation , which feature artworks depiciting falling objects frozen in midair. Additionally, the artist says, “Once in a while I dream of flying.” In the dream, she said, “I was originally a child who could fly … I had forgotten that I [artist] could fly”, “I am aware of this” and “float into the air” (artist’s note). The artist’s dream of flying seems to be the background for the series Self-portrait, The Tempest, and Lucid Dream which express the image of sublimation.

In the world, gravity (centripetal force) that physically attracts us and centrifugal force that lifts us up due to the rotation of the Earth, exist at the same time. One of the various interpretations of ‘heaven’ by Jean-Luc Nancy is that from the end of the Earth, that is, from above the surface of the Earth, the sky begins and theologically, heaven is everywhere because it is nowhere (God, Justice, Love, Beauty: Four Little Dialogues). In other words, below our feet is the ground, but above our feet is the sky. The sky is a space where divine beings live. If then, we stand on earth and live in heaven which is nowhere, thus everywhere, and we live with the divine beings in heaven. Therefore, both descent and ascent occur in heaven where we live with divine beings. Simone Weil said in Gravity and Grace, “Creation consists of the descending activity of gravity, the ascending activity of grace, and the descending activity of the second grace. Grace is the law of descent.” Ahn’s work is not unlike Simone Weil’s ‘Creation.’ Her work demonstrates the dialectic of descending and ascending. The work takes us to a new level of gravity and grace.

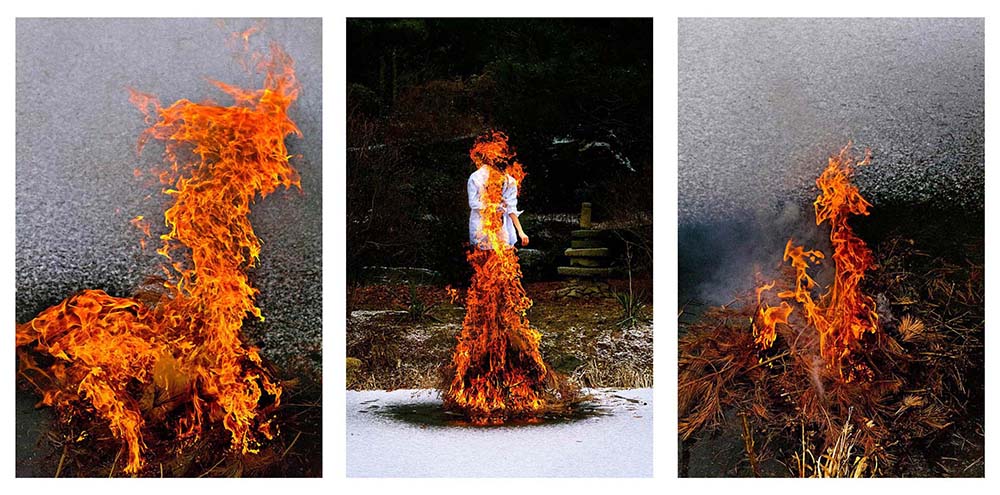

We should not think of the artist’s work as just a dichotomy of the descending activity of gravity and the ascending activity as its reversal. In her work, descending and ascending are intertwined in a complex way. Such characteristics are well demonstrated in the series Self-portrait. When “the moment I thought I was standing on the edge of a cliff” (artist’s note) came into the artist’s life, she stood on top of a high-rise building with the feeling of standing on the edge of a cliff. From atop, she captured both the dizziness of looking down and the freedom she would feel when floating in the air. It captures the feeling of descending and ascending together. The Self-portrait series, which was presented from 2008 to 2013, captures the dizzying past under her feet (time to climb up to a high-rise building) and the free future unfolding above her head (time yet to arrive). The Self-portrait series presented in 2021, however, has more spiritual and transcendent aspects. This work seems to be the last farewell with her maternal grandmother. Recalling the reality that she is no longer able to see her grandmother who raised her, the artist captured fire and flowers, winter, and her grandmother’s garden and empty house in the work. In this series, a jump, a flower facing upwards, a burning flame, and ashes floating in the air–all rise upwards, but in the end, one falls after jumping, a flower facing upwards is actually facing downwards, and the flame rises but the warmth revolves around it, and the floating ashes will someday settle on the ground. As long as the artist has memories of her grandmother, her grandmother exists here, because the place we stand on is the sky. All of these slightly different Self-portrait series unite the moment of life with a physical phenomenon that could be considered dichotomous.

Timelessness Expressed by High Sensitivity and Deep Depth of Focus

Ahn Jun transforms an irreversible phenomenon into a frozen time that “stays still.” However, this time is not ‘paused’, because this moment is the present that embraces the past and the future. Some would call it ‘a fleeting moment’, but this moment implies a timeless conception of nature that is closer to ‘eternity’ rather than an instantaneous moment. This time belongs to our time, but it is a time we do not know.

In the series One Life and Liberation are works that successfully demonstrate this timelessness. The artist said, “Living a life is … a process toward the end, just as an object falls to the ground by gravity” (artist’s note). If so, then these series can be read as metaphors for life. The artist likens the irreversible situation of apples and rocks subjected to falling due to gravity, to our ‘one-off life’. However, the artist changes this metaphorical ‘one life’ into an eternal one. In her work, she reveals the one-off life, that eternal life, which “no longer changes and remains as it is”. In order to show this moment, the artist throws apples, erases the traces left by the fallen apples, repeats the throwing dozens of times, and takes hundreds of photos. In the end, dozens of actions and hundreds of photos are produced to create One Life and Liberation. It is not unlike the accumulation of similar lives, such as ‘multi-universe’ or ‘superimposed life’. From a different angle, it looks like a symbol of undifferentiated time. A fragment of this time is selected and this becomes a work. Therefore, one work may seem like capturing a moment, but intrinsically it touches on the idea of ‘eternal return’ that our lives are repeated and overlapped over and over again. The moment the artist has shown exists in life, yet it has an inherent timelessness that exceeds life. In these series, we feel the memories and wishes of her childhood “of not wanting to grow up anymore” (she wanted time to stop). Additionally, there is also a desire to live a life that does not lead to death, over and over again.

Ahn Jun was able to reach timelessness because she reacts sensitively to life and approaches it in depth. Her sensitivity and depth towards life are analogous to the camera’s sensitivity (ISO) and ‘depth of field’ (DOF). What freezes the falling apples and rocks, blazing fire, the raging stream of discharged water, and the breaking waves (The Tempest series) is the camera’s shutter that opens and closes almost imperceptibly fast. In other words, high speed photography plays a significant role. However, the timelessness that crosses the time and space of the past and the present is achieved by the ISO and DOF. A fleeting moment can be imprinted as a moment of eternity because of the high sensitivity that allows susceptible perception of the moment. As the camera’s sensitivity increases, the ‘noise’ (artifacting) in the image increases, making this moment feel like a scene in the vague memory, a scene from the past that has been experienced and repeated many times, rather than a sleek hyperreality. Additionally, by tightening the aperture, the depth of field gets increased to obscure the sense of distance to the object. Because of this, the distant, middle, and near-view are aligned in one coordinate and appear to be in the same position. The illusion begins. (Especially in the Liberation series, this characteristic stands out. A nearby stone looks like a large rock, and the background behind it looks relatively small. Although the two are in significantly distant places, they appear to be in a similar position due to the deep DOF.) The artist creates a transcendent space by converging a wide open space into one coordinate. This is a spatial manifestation of the characteristics of Ahn’s work, which converges the past, present, and future into a single point on the axis of time and captures it in a fleeting moment.

Among the artist’s works, there are some with a strong sense of ascent. Lucid Dream is the case along with Self-portrait series (2021), which captures the burning flames. They, however, also bring to mind the dialectic of ascending and descending. For just as apples and rocks must be thrown into the air (ascending) before they fall (descending), flying entails descending. There is a saying that even a footless bird that is said to rest in the wind comes down to the ground only once in a lifetime when it dies (lines of Cheung Kwok Wing in the movie Days of Being Wild). Ascent is accompanied by a descent, and descent is a motion that does not exist if there is no ascent. Ahn’s work implies ascent in descent and descent in ascent. The artist dialectically unfolds the descent and ascent, leading us into the world of timelessness.”

From “Time and Space of Gravity and Grace:Dialectic of Descent and Ascent by Lev AAN (Art Critic)

On Gravity

Perhaps that day was the first time in my life I thought about death. My mom still remembers the day in my childhood when I said I didn’t want to grow up anymore. When my mother asked me why, I said, “If I grow up, mom and dad grow old and people die when they are aged, so I hope all of my family remain unchanged.” I can’t remember how my mom answered, but I remember that she hugged me tightly at that time, and that it was afternoon before the sunset and I was looking over my mom’s shoulder in her arms and saw the pattern of sunlight which entered through the window on the right and permeated into the wall. I looked at the pattern and thought “this is so scary.” My birth was not my choice, but once I was born, I grow up, get older and die, and am then separated from my mother, father and younger sibling. So it is scary.

I felt being alive is like being an object thrown into space, subject to gravity. No choice, only running towards death, passing through time and space. I thought ‘free fall’ sounds inappropriate because something is pulled down by gravity and fall toward the ground, the center of the Earth. So I looked up the English dictionary and found that the word ‘free’ is also used in the English expression “free fall.” It is natural for something to be affected by gravity in the air, but from the view of a falling object, why is it called free when it has to fall until it hits something without any way to resist it? I was not conscious of it at the time, but the memory of that day remained somewhere in me, and from that time on, many things that other people said were meaningful were meaningless to me. Thinking that one’s life is a process of going towards the end, just as an object falls to the ground by gravity without any resistance, I couldn’t really give a lot of meaning into something and continue it; I was just looking for something interesting from time to time. In fact, many things depended on luck and chances rather than effort, and efforts were only necessary so as not to have any regrets in retrospect.

One’s life is longer than an object’s free fall, but from the perspective of a stone, a tree, the Earth, or the universe, it is a phenomenon that is more irreversible and instant than anything else. For this reason, I liken the process of free fall to ‘memento mori’ in my work. Two phenomena of different lengths, one’s life and free fall, begin and end involuntarily and they are irreversible. And ‘how’ to get to the end is affected by a coincidence, which is a combination of will and environment. For that reason, through my work, I wanted to find the accidental beauty that arises from free fall. I wanted to find meanings in the process and the act of capturing a shape that would have been unrecognized and gone if I had not stared at and shoot them. So I repeatedly asked my family to throw apples or lift and drop stones. By repeating the act of sequencing through high-speed photography of the process of free fall (which is faster than our visual perception), I tried to discover and commemorate the beauty of a locus created by chance amidst irreversible phenomena.

As a child, I said I didn’t want to grow up to prevent my parents from aging, and now I’m a little older than my mother when she heard my wish. Before and during this time, the Earth rotates and revolves around the sun. The solar system also orbits the galaxy. If we mark the coordinates of our existence in the infinite universe, no one will stay in the same place for any moment. Nevertheless, we meet and break up with someone, and we share a common memory. Because of that memory, being a grown-up was not as scary as I thought. If all you want to do is run towards the end and encounter death, then there is no meaning for being alive; rather, meaning would be something like a composition on a screen created by chance, as coordinates that started in different places fall in different directions. I believe that capturing, remembering, and appreciating the beauty of the moment would be equivalent to being there. -From Ahn Jun’s Artist’s statement

Sunjoo Lee: Would you explain what inspired you to start photography?

Ahn Jun: Since kindergarten, I wanted to become an artist. I loved to draw and I was very interested in art, but I was afraid to present my own drawings. So when I was young, I thought that becoming an artist would be difficult.

While majoring in art history at university, I studied various art subjects and thought I wanted to try making art. As an intern at the Shanghai Art Biennale, I worked as a research assistant, and I felt the charm of photography in the darkroom class I took in my 4th year of college. Photography records the outside world through a camera, and I was fascinated by the creation of results that were different from the world I had seen. I wanted to cover the gap between the world we see and the result of photography. I think it was these things that motivated me to become a photographer.

SL: Please tell us about your first project, Self Portrait, which received a lot of attention?

AJ: Personally, I liked the work of Jackson Pollock, a representative abstract expressionist artist, and I was interested in his dripping performance.

I wanted to give my own definition of time through the medium of photography. In other words, I wanted to do the work of substituting space for the time I perceived with photography. In that respect, it is also related to the dripping of Jackson Pollock.

My <Self Portrait> work started around 2008 when I was in graduate school in the US. At that time, Photoshop became popular and many photographers were working on compositing the real and the virtual. However, my interest at the time was to go against this trend and to directly implement unrealistic scenes such as composites.

I took a picture of myself sitting or standing on the edge of the roof of a high-rise building at the time. It started with my fear of heights. It was interesting to see that when the context of fear shows only one image that is opposite to the context after shooting, it overturns the original meaning of fear and leaves the impression of thrill seeking or playful. I myself became the main character of the photo and stood on the edge of the roof, thinking about the moment of time.

I thought that the physical height of the roof was like my past, the edge of the roof was me stepping into the present, and the view from the roof was like an impossible future. My Self Portrait project reveals my definition of time, past, present, and future.

SL: Self Portrait series and On Gravity series seem to have a common theme. What theme are you expressing through your work?

AJ: My On Gravity series repeats throwing, dropping and picking up objects. It is an image of reality created through the process of high-speed shooting while looking at the same point. The pictures are strange because we cannot see these moments passing by so quickly, but this is a project to reveal the surreal moments that exist in reality. This is a metaphorical explanation of the time in which we live through events taking place in a certain space. In other words, we compare our lives from birth to death to the principle of free fall until a thrown object hits the ground by gravity. If gravity is a law of nature, there will be moments of conformity to it and moments of reversal. So, this project consists of the works that stopped in the middle of the descent and the work that expresses the direction of ascent against gravity. I am talking about the time we live in as the moment of descent, and expressing death or dreams as images of ascension.

Meanwhile, my artistic discourse in Self Portrait is concerned with the relationship between photography and performance, and the surreality revealed in the photographed reality.

In conclusion, the two series are connected to the empty air, free fall, and the moment of life, and they have a common theme that reminds us of Memento Mori.

SL: Please explain how the meaning of women’s life expressed through the On Gravity series is related to your work.

AJ: The work itself and the motivation is not about gender issue. However, it made me think about life as a woman during the process of working with my mother and my grandmother (mother of my mother) who passed away one and half years ago. The series of works is about the beauty of coincidence comes out from repetitive performance; throwing apples. I ask my family, sometimes my friends to throw apples over and over until I get the composition I want. As you can imagine, the process itself is repeat of simple and bit boring routine. I was quite surprise that my grandmother really enjoyed that. Then after few years I realized that she liked it because simply it can be a support for my career: making work.

Looking back into her life, I realize that her entire life was about distribution for others mostly regardless her choice, like most of woman did in her generation who was born during the Japanese colonial period, married during the period of Korean War, and raised three children during post-war period. She was housewife although she was smart, and social due to the lack of opportunity. Some, very few women resisted to it, but she chooses to enjoy her time as it was. Because of the social environment during her age, many women in her generation encourage her daughter to have a career, job, and any kind of accomplishment in one’s own life. Then what about her daughter’s kids? Most of generation chooses to take care her grandchildren for her druthers’ career. This is the reason why many people in my generation like I am who have working mother normally have close relationship with their grandmother, especially mother’s mother.

I started both projects One Life and Liberation from the same her I got married; although it is titled later, but started make images since 2012. It is also the year I back to my hometown after 10 years living in US. Although the work is about liken our lifetime to gravity, and capturing transcending moment, the time for the performative practice itself made me spend time with my family, and think about my mother’s and grandmother’s life in different perspective after childhood. I think it lead me to made my self-portrait in my grandmother’s empty home and her garden after she passed away.

SL: You have been working on repeating the act of throwing an object into the air. This performance seems to metaphorically express the message of “memento mori”, the message to remember death, and the law of gravity, in the state of being entrusted to the natural principle of “free fall”, the concept of time and space, that is, all humans eventually die. This can be seen as one of the basic fears or insecurities that all humans experience rather than being specific to women. In particular, what kind of connection do you have with your performance work from women’s point of view? Please explain in detail if there is a point you want to talk about in particular from a woman’s point of view.

AJ: 2. Each of my project based works are highly autobiographical in terms of title. It alludes different period in my life, and the theme that penetrates every works is ‘gravity.’ This perspective is generated from my thinking-maybe my fear-that the ‘life’ is basically a kind of passive phenomenon; we never choose our gender, country, parents, and most importantly did not choose to be or not to be.

Commonly photography is thought to be towards to the “object.” However I see every being outside of the world as a ‘phenomenon.’ I consider our lifetime as a phenomenon too; it has longer duration than an object’s free fall or lifetime of dog, but from the perspective of stone, tree, earth, and universe, it is a phenomenon that instant than anything else. Hence, I liken the process of free fall to ‘memeto mori’ in my work. From this point of view, series title One Life is also took after Thomas Carlyle’s word, “One Life : A little gleam of time between two eternities.”

Like you pointed out that my work is more about fundamental concerns of being itself rather than being as a female. However, I believe it will be or have already revealed each of story underneath it since I was born as a woman prior to my choice from the beginning of my life.

SL: As a female photographer, what do you see as your role in Korean society?

What kind of effort would you like to make if you give responsibility or meaning to your role?

AJ: Like my previous answer about the issue, gender is not appears in front. It is partly because my gender never been a big issue or struggle in my life, and I think this is very important point. Virginia Woolf wrote that “a room of one’s own,” that “a woman must have money and room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Her words show that it is very hard condition besides literally money and room as physical space, even during the 20th century in most of countries. Throughout history of Korea, my generation is the first women who have her ‘own room’: after post war period grandmother, and working mother as a kind of role model. On the other hand, I recognize that this is the result of devotion of women of post war period, struggle of women who tried to expand space for women in every social structure, effort of mothers who educates their children against all kind of discrimination, and rapid economic development of Korea. And I am one of a lucky individual woman who has ‘one’s own room’ at the limited intersection of all the conditions above, although the size of Korean economy itself is more than enough for better environment for women.

One practical example can prove there is serious demanding for improvement of consciousness of women’s social right. According to the report of the Seoul city on 2021, Korean men still do less housework than the most, and women spend nearly four times more hours on household chores than men. This practical routine of women in statics reflects gender consciousness of public and its practice are the most indispensable matter for actual change. At least, I hope my life as a women artist shows positive example for future generation. And as an artist, educator, and as one person, I will keep make effort to be remained not only as “an artist who has her own room,” but also as a person who stand in solidarity with others against all kinds of discriminations.

SL: After returning to Korea from studying in the United States, you received your Ph.D. at Hongik University and taught at universities.

Did your experiences and feelings in the process of guiding young students influenced your work? If so, what effect did it have?

AJ: There was a change in my personal life when I started to teach at universities. At the same time, I saw young Korean students doing their best in the present. However, I could feel the anxiety of young students about their future life as artists. Like everyone, I have also experienced uncertainty and anxiety about the future. I wanted to look at the anxiety that students currently have and find beauty in the anxiety that comes from accidental intervention. I think it was the beginning of a visually repetitive and accidental performance.

In other words, the beauty of chance is shown as a phenomenon that falls out of my work. A phenomenon called life is a very brief phenomenon of a single moment in the long history of the earth’s creation.

SL: Korea’s modern history has undergone major changes in a short period of time after the Korean War. In particular, your generation was born in a relatively stable era due to the economic and cultural development of Korea, and it is thought that they experienced a life different from that of their parents’ generation. Nevertheless, do you have any opinion on the patriarchal society in Korea experienced by your parents’ generation?

AJ: I think our generation was born and raised during a period of economic revival and socio-political stability in Korea. Although women are living in an era of freedom rather than their parents’ generation, as a human being regardless of gender, the weight of each individual’s life is thought to have a different meaning from the times.

I think it is a generation that thinks more about the role of women in the equal position of women and men than the subjects and objects of resistance or oppression. Unlike the oppression of women in the patriarchal society of my parents’ generation, I think the concerns about the role of women today are greater. In the end, I think I’m thinking about the fundamental weight of human life and anxiety about death rather than gender differences.

SL: Lastly, please briefly explain the meaning of gravity in your work.

AJ: I had a special relationship with my maternal grandmother. She had filled my mother’s vacancy due to her teaching position, and she was the one who always supported me and made me happy. She died after Corona, and the situation was too unrealistic for me. Many of my works, including the apples that my grandmother threw away, the floor of my grandmother’s house, her empty garden, and the time we burned her clothes, leave traces of her in many of my works.

The reality of death, which I have experienced emotionally since my grandmother’s absence, has been likened to free fall, and stories of souls or dreams mean ascension in the end.

“Ahn Jun’s works reside at a place neither here or there. Of course, s?he focuses on a subject like any other photographers, but the resulting photograph depict a moment neither here nor there; rather, it is situated in between here and there — a nonexistent scene, sandwiched in the midst of reality and unreality, making the photograph look surreal even. Ahn Jun presses the shutter button at an imperceptible place posited in between the visible.”

From Click! Freezing spacetime with a shutter—-a nonexistent scene. By Nathalie Boseul Shin (Chief Curator, Total Museum

Sunjoo Lee is a mixed media photographer based in Seoul, South Korea.

Lee’s extraordinary artistic sensibility that was once portrayed through her voice is now visible through the works portrayed through her camera lens. Her photography focuses on a unique lyrical journey into her personal life. She explores her past, present, and future world in a temporal and spatial perspective.

She received a BA in Music from Ewha Women University, a second BA in Photography from Chung-Ang University(Academy credit bank system), and an MFA in Plastic Art & Photography from Chung-Ang University Graduate School of Photography in Seoul, Korea. In 2019, she was awarded into the 11th cohort for the prestigious artist residency program at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary Art. Through this residency, she’s currently working on her upcoming series.

Lee’s acclaimed works have been exhibited widely throughout the years in South Korea. Most recently, she had her solo exhibition at the Youngeun Museum of Contemporary art, Gwangju Korea. She’s also showcased at Gallery Now, Gallery Gong, Gallery Guha, and more in Seoul, South Korea. Her works are permanently displayed at the Haslla Arts Museum (Gangneung, Korea), and YoungWol Y. Park (Youngwol, Korea).

Her work at large, incorporates everyday objects and subjects to make visual sense of the complexities of human emotions and feelings derived from the intangible, such as music. Her photographic inspiration stems from her experiences of living and travelling abroad. She extracts the memories and various emotions born out of the human connections she’s made during that time of being in foreign spaces.

Building on this conceptual narrative, her work has landed her multiple recognitions, from the 2019 Critical Mass as a top 200 Finalist (USA) to the 1st Place Richards’ Family Trust Award during the 25th juried show at the Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, USA). In Korea, she was received the Dong Gang International Photo Festival’s Now and New Exhibition award.

Follow Sunjoo Lee on Instagram: @sunjooleephotography

Thank you to Jisoo Kim for her excellent translation

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Gadisse Lee: Self-PortraitsDecember 16th, 2025

-

Katelyn Lux Brewer: TICSeptember 7th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: A Mindfulness Practice with Christine CluffApril 25th, 2025

-

Riley Goodman: Art + History Competition Honorable Mention WinnerApril 4th, 2025