Photographers on Photographers: Daniel Hojnacki in Conversation with Shoshannah White

© Shoshannah White Setting a Pulse, Installation: Center for Maine Contemporary Art, 2022, Scale: 108”x112” Individual pieces: Left: Lightning Inversion #3, Pigment print on panel with mixed media. Right Magnetics #27: Rock Dust. Pigment print on wall-covering with mixed media. (Original exists as photogram print made from gathered rock, pulverized and activated by magnets. Shown work was scanned, enlarged and worked with media.)

I learned of Shoshannah White’s work while I was a graduate student at the University of New Mexico. Their work was published in Southwest Contemporary Magazine as one of 12 New Mexico Artists to Know in 2021. Quiet, yet intense abstracted forms hovered on the surface of Shoshannah’s black and white images. Imbued with a sense of mystery and haunting beauty, I knew from the first time I saw White’s work, I needed to know what it was I was looking at or looking for rather.

About a year later in 2022 I brought one of my UNM darkroom photography classes to see Shoshannah White’s solo exhibition “Setting a Pulse” at Richard Levy Gallery. I was again captivated by Shoshannah’s experimental and scientific transformation of material with the photograph. It was exciting for students to also see how a photographic artist was manipulating the surface of images and exploring exciting and unique ways in which a photograph could be exhibited.

Although only meeting once briefly in person during my time in New Mexico, I have been returning to Shoshannah’s work for inspiration a lot. Shoshannah White makes tangible a way of articulating and seeing the overlooked wonders of the natural landscape, which are given close and careful consideration. I feel themes of photographic experimentation are undeniably what Shoshanah and I share in our practice, but I also see a relationship in our curiosity to poetically visualize the fragile and wondrous world around us. I was so excited to have the opportunity to take a deeper dive into White’s work with this interview.

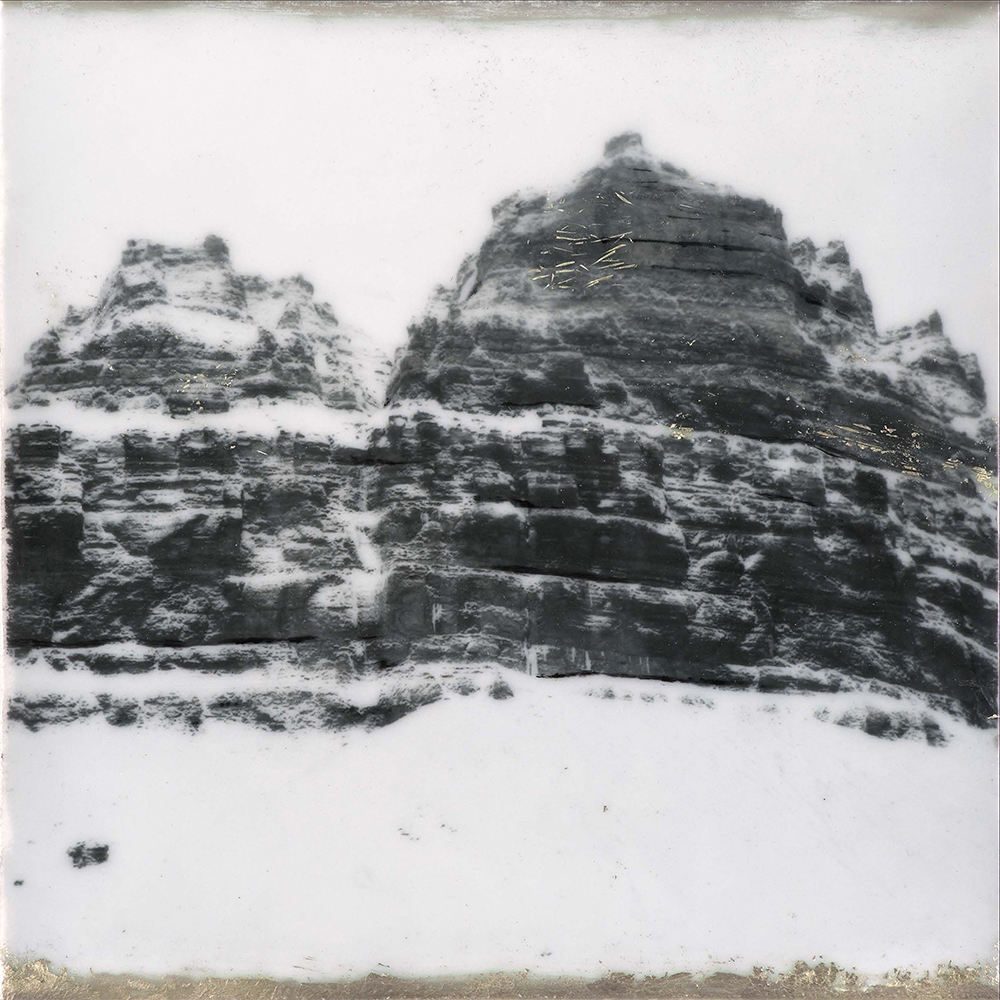

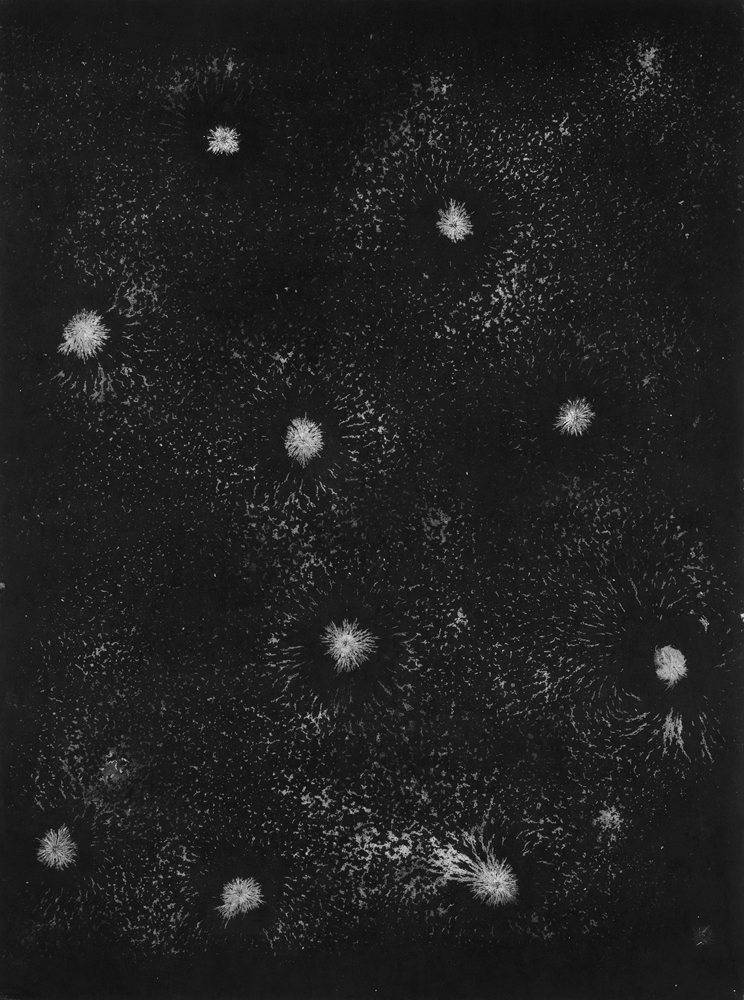

© Shoshannah White Magnetics #34: Iron, 2017/2022, Scale: 48”x36” Pigment print on panel with mixed media. (Original exists as photogram print made from iron dust activated by magnets. Shown work was scanned, enlarged and worked with media.)

Shoshannah White is an interdisciplinary photography-based artist currently dividing time between New Mexico and Maine. Her work is multilayered and spans photography, painting, sculpture and public art installation. Shoshannah’s research-based, non-linear approach has led her to work in New England Forests, Arctic landscapes, Pennsylvania coal mines and next to receding glaciers in Alaska to create projects related to particular ecological systems, landscapes, threatened plant species and/or raw materials. Working with ideas of repeating patterns and natural phenomena, the work exists as objects for exhibition, editorial content and installation pieces.

Her work has been exhibited at institutions including the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Center for Maine Contemporary Art, George Eastman House, Maine Jewish Museum and Roswell Museum. Shoshannah has produced permanent and temporary public art installations. She has received awards and support for her work and her photographs have been featured in publications including The Wall Street Journal, Der Spiegel and online in MIT’s Climate-X and Scientific American. Shoshannah has completed artist residencies in the United States, Canada and Norway, and has been a visiting artist at institutions including Bowdoin College, Dickinson College, and at Harvard University’s Research Forest. Her work is represented by Corey Daniels Gallery in Maine, Richard Levy Gallery in New Mexico and work is available in Canada at Stephen Bulger Gallery.

Follow Shoshanna White on Instagram: @shoshannahwhite

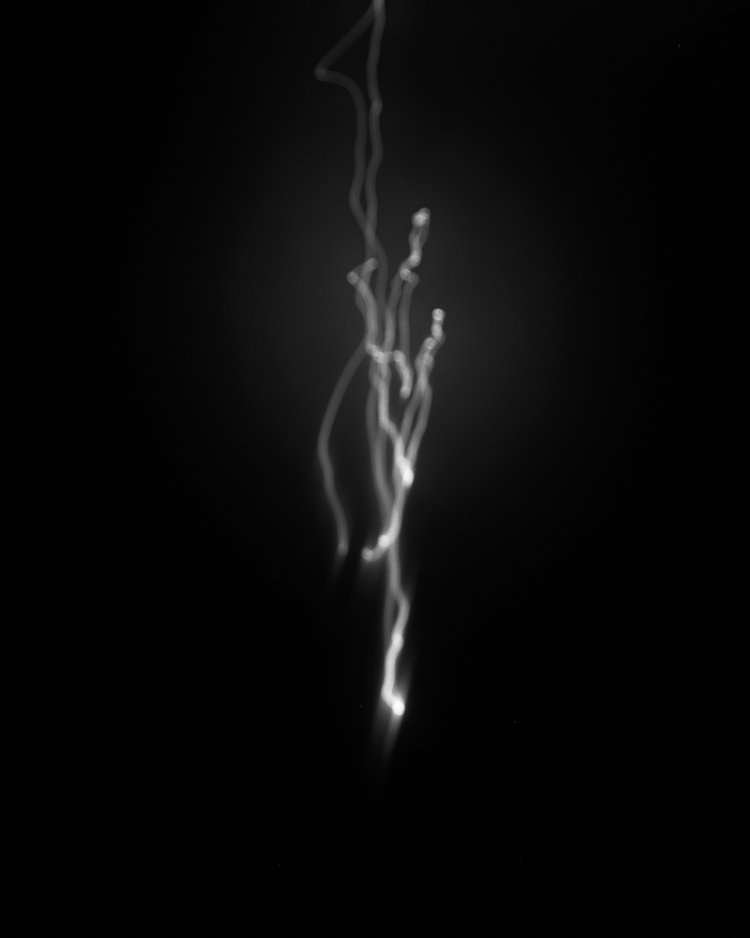

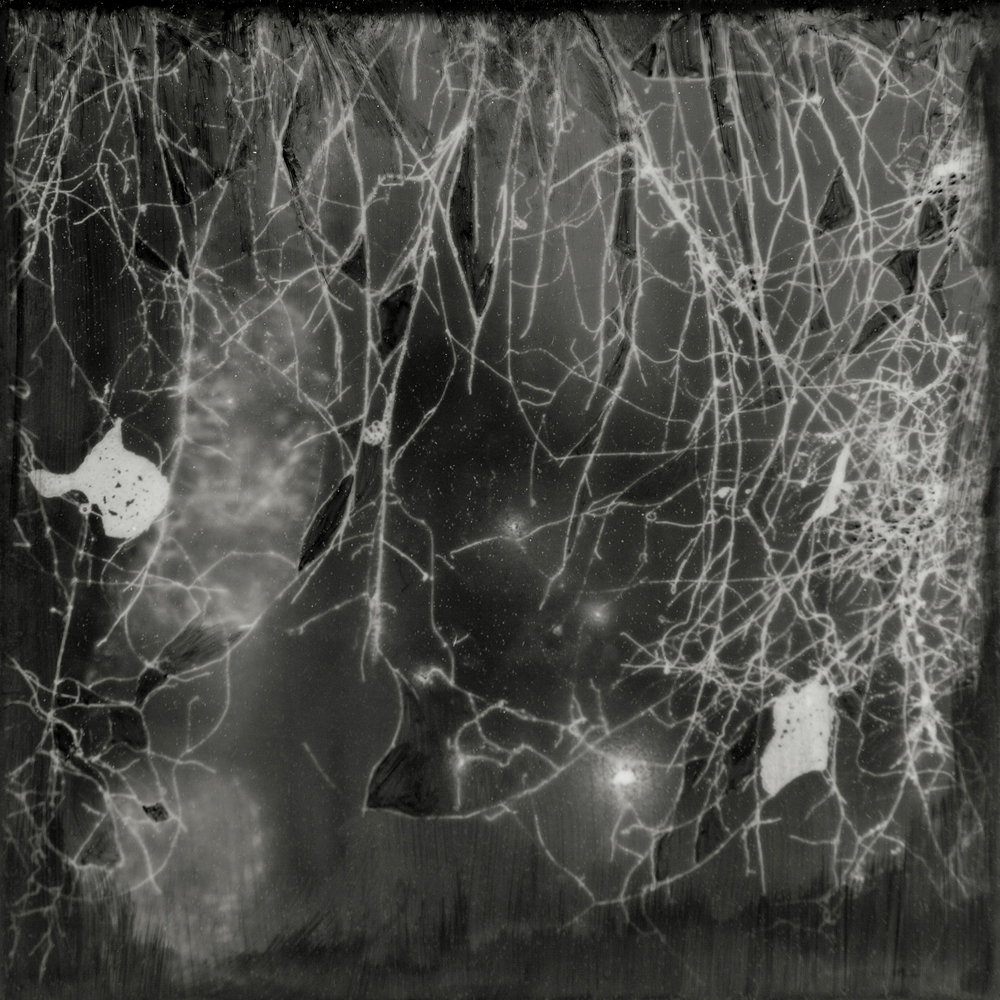

© Shoshannah White Lightning #3, 2019/2022, Scale: 36” x36” Pigment print on panel with mixed media.

Daniel Hojnacki: A recurring theme I am drawn to most in your work is the unseen phenomena taking place in the world around us. What drew you to start using photography with this type of investigative approach?

Shoshanna White: I’ve always been interested in the idea that things are not necessarily what they appear to be and in how they shift based on time, light and perspective. I’m fascinated with unseen worlds – whether that’s a psychological world existing between people, or a physical world such as underground root systems, hidden information in glacier ice or the invisible forces of magnetism. My family is filled with psychotherapists and artists and I had an early introduction to other forms of communication aside from language: body language, symbology, visual art. For years I made portraits in an attempt to capture that tenuous connection and disconnection we have with each other – exploring a kind of space between people – where you can see or be seen yet never decode exactly the experience of another. At a certain point, I started literally going under the surface of things: underground, underwater, into the dark – in an attempt to access unseen worlds. Materiality plays a big role in my work as well. For example, I’ll often incorporate media onto the surface of photographic works, such as wax, paint or metals – materials which themselves create a distance between the photograph and the surface – obscuring parts of the underlying image or accentuating others where the material can take on its own agency and may appear or disappear depending on the angle of viewing or the reflection of light.

©Shoshannah White Magnetics #10: Iron, 2017/2022, Scale: 36” x36” Pigment print on panel with mixed media. (Original exists as photogram print made from iron dust activated by magnets. Shown work was scanned, enlarged and worked with media.)

DH: How did you end up working in Norway? It seems that was a big catalyst to the trajectory of your career, and resulted in some incredibly strong work.

SW: Thanks so much. It was definitely a significant experience. At the time, I was interested in being in a part of the world so altered by humans but with what I imagined would show very little physical evidence. With this interest in the invisible nature of a changing climate, I applied to the Arctic Circle Residency – which is a three week sailing expedition in Svalbard, Norway and was lucky to be able to join in 2015. We’re living in a time when there’s really no untouched area of the planet, still, I’d imagined the Arctic as a pristine environment, despite the massive changes that are taking place with ice melt and emissions and wanted to be on-site to understand it differently – to tune in a bit more deeply to what’s at stake. When I was there, I made images of the extremely impacted yet still sweeping, romantic glacial landscape. I also photographed icebergs both above and below the surface of the water. At some point I realized I needed to augment the beauty of those images with something more data-driven and empirical which led me to the Prince William Sound in Alaska where I chartered boats to receding glaciers, set up a temporary darkroom and made photogram prints directly from glacier ice. It’s been almost eight years since the Svalbard trip and I still think about it practically every day. The work and connections made during that short time has led to multiple projects and collaborations since.

© Shoshannah White Unseen Networks Installation: Bates College Museum of Art, 2015, Scale: Nine works at 6”x6” each Pigment prints on panel with mixed media. Imagery shows microscopic captures of mycelium, underground root structures and branching tree canopies.

DH: What research has impacted your practice? Are there books or writings that get you out of a creative block or feeling stuck?

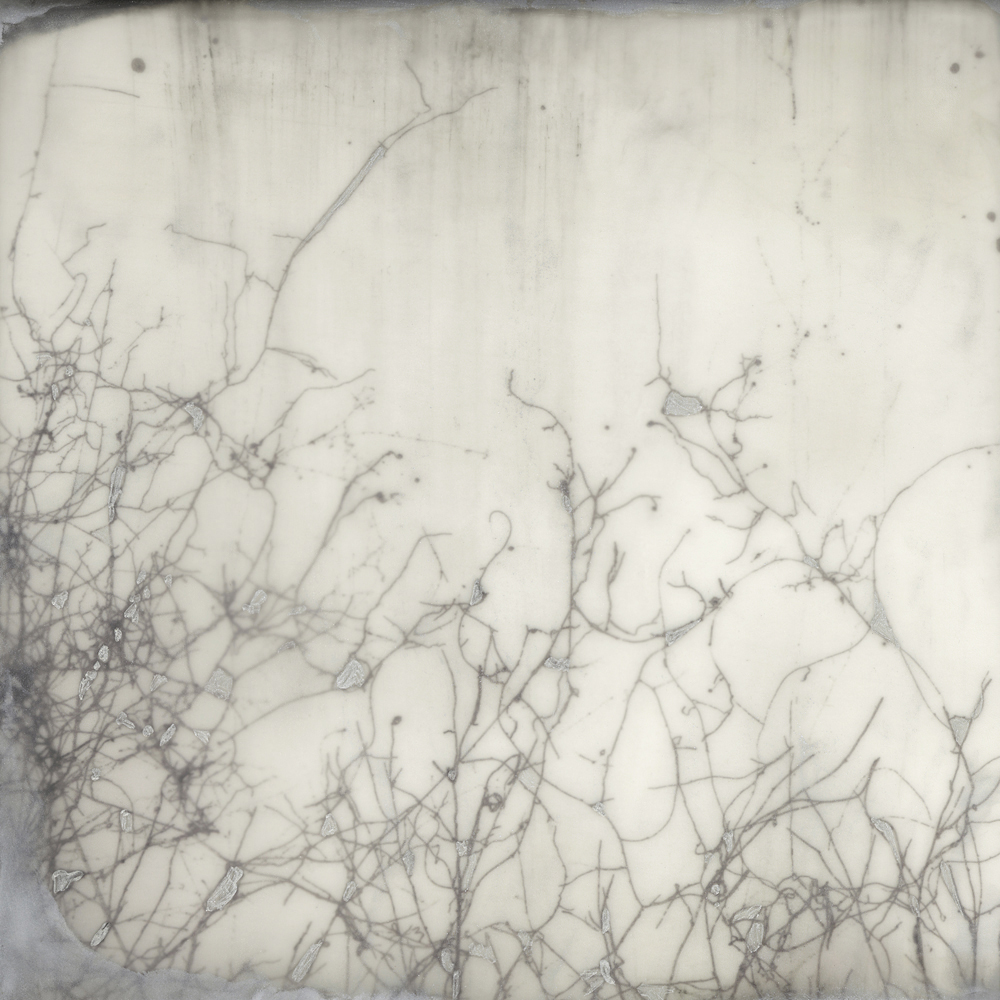

SW: Yes, my work is definitely research-based but it’s also non-linear. It’s inspired by science, the environment, natural phenomena and our human experience, though I don’t have a brain for traditional research. Still, it’s a huge part of my jumping off process. I read anything from poetry to scientific journals to try to wrap my head around the specifics of place – the history, the present, the future – deep time, but ultimately, I follow my curiosity and then I show up and respond more intuitively. When I’m between projects or feeling stuck in some way, I try to shake up my process – I might use different equipment or techniques to get me out of my routine – microscopy, root-scanners, cliché verre – or work in other media: drawing, sculpture, ceramics, etc. I find it helps me re-orient and let the materials, the content and the experience surprise me with a kind of informed playfulness. I’m also a fan of physical practice – walking, meditation, yoga. I read once, since we’re mostly water, we need to move or we become stagnant. My work is a very physical process and I’ve learned to gather, handle and let the raw matter of place help reveal next steps. For example, with the Unseen Networks project, I knew I wanted to make a body of work about repeating patterns in the natural world. I started researching – became obsessed with Suzanne Simard’s work tracing communication between plant species via mycorrhizal fungi. This led me to work with a local mushroom farmer who grew mycelium specimens I was able to capture microscopically at Bates College’s lab. I wanted to reference the form of a traditional, microscopic glass slide. This prompted me to learn the ambrotype glass process – resulting in three-dimensional works related to the organized chaos of the mycelium itself. And on and on, it’s a kind of bread crumb trail which I’ve learned to trust over time. Some of the writers related to my work I’ve been reading over the last years are Alison Hawthorne Deming, Terry Tempest Williams, Barry Lopez, Rebecca Solnitt, Robert MacFarland, Richard Powers, James Bridle is a new discovery.

© Shoshannah White Mycelium Bramble, 2015, Scale: 6”x6” Pigment print on panel with mixed media. (Original exists as microscopic capture of mycelium grown by Maine-based mushroom farmer.)

DH: The reminder of interconnectedness is a beautiful concept that threads through your projects. It is a humbling one that is also a reminder of how our actions can affect one another over great distances perhaps, and that we as a human species are not only interconnected to one another on this planet but the natural world as well. What are your thoughts on this theme in your work?

SW: This is such a lovely, thoughtful question. Yes, I’m constantly in awe of the interconnectedness of all things. I remember as a kid learning about the water cycle, cloud –> rain –> river –> ocean –> repeat, and the interplay of water systems. I was obsessed with thinking about the shape-shifting quality of water and how we are mostly water, a thin line of skin on the periphery separating us from the larger world, keeping us from lifting off into a cloud. Growing up on the coast, swimming, I would think about water meeting water as I slipped in. Now to think about the plastics and toxins we’re circulating around the globe, the dark particulate from industry landing on the glacial ice, speeding up the melt, water circulating from polluted river, nuclear waste buried deep in the ground, fracking seeping into the water table, it’s all part of the same system. It’s not all grim though, there’s a beauty to it all — the dance of life — one form morphing into another. A fallen tree becomes a home for countless other creatures, replenishing the soil, all while storing the carbon it’s consumed all its life, the yucca and its moth survive because of one another. We’re all connected and also disconnected. We have autonomy – but not really. Scientists say even our individual bodies are a consortium of organisms. We’re constantly absorbing and expelling information, energy. One of the things we were reminded of in these last years during the pandemic is how our breath is an exchange and shared experience. It’s all so layered.

In my work, I try to respect the interconnectedness and wonder about the specifics – seen and unseen. I’m interested in abstraction and metaphor. Where lines between the interior and exterior experience are blurred.

© Shoshannah White Mycelium Lace, 2015, Scale: 36”x36″ Pigment print on panel with mixed media. (Original exists as microscopic capture of mycelium grown by Maine-based mushroom farmer.)

DH: Your work moves between elements of both painting and photography, are there artists who you admire that influence your choice of materials and how you handle or apply them to your work?

SW: Well, I consider myself a photographer but I’ve always worked in other media. Material exploration is an important part of my practice. I’m not sure if I look to other artists for material inspiration. I’m more paying attention to an individual project while adopting new techniques or incorporating materials which make sense physically and conceptually. There are approaches I return to regularly but I’m often experimenting with extending the boundaries of my toolkit. In a lot of my work, I’m interested in a kind of hybrid between drawing and photography and the photogram has given me a perfect way to combine the two. I try to maintain a healthy mix of representational, organically familiar, with enough abstraction to keep things mysterious. Often, the materials themselves can change with time, light and perspective (wax, paint, glass, metals, graphite) which have their own properties and reveal.

There are so many artists, writers, musicians I admire – it’s just impossible to narrow it down. The artists that consistently ask the hard questions and have continued to evolve over time are the most inspiring to me. Louise Bourgeois is someone I return to again and again. I love David Altmejd’s use of materials and work that has the ability to shift – Mark Rothko with his levitating worlds, Ursula von Rydingsvard’s sensitive and profound jaggedness, Terry Winters’ dark inky magic. Kara walker’s silhouettes, Maya Lin, Agnes Denes layered and considered relationship to material and land – it’s endless.

© Shoshannah White Unseen Networks, Installation: Bates College Museum of Art, 2015, Scale range: 6”x6” to 132”x144” Installation showing a variety of photo-based processes and techniques including ambrotype glass plates, digital and analog photography with mixed as well as microscopy.

DH: How has your work changed or evolved over the years?

SW: Well, I’ve always been interested in the constancy of change and the idea that we’re each part of an endless cycle of becoming something else. At an earlier time in my work, I think I approached those themes through portraiture in an attempt to bridge a gap of understanding. In the last few years, I’ve become more interested in letting the questions remain unanswered. Looking more at the mysteries – unpacking my internal world through an external experience. I think my relationship with creativity has also shifted. Earlier, I think I understood creativity as something you had to start with, at this point, I think it’s more something that emerges out of the act of working – of beginning. There are teachings everywhere in nature and I find, more and more my job is to listen and learn from multiple forms of intelligence. I’m in a place now where thinking about geologic time gives me access to a different kind of acceptance and the work has become a kind of byproduct of exploration.

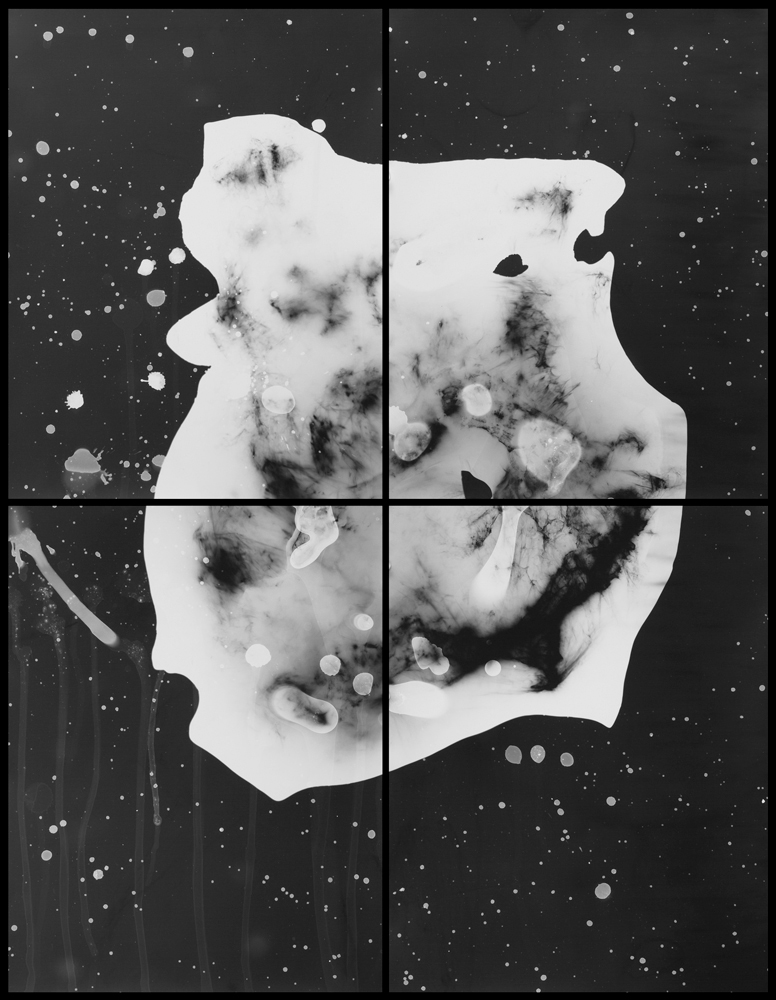

© Shoshannah White Barry Glacier Ice, Four Panel, 2016, Scale: 28”x22” Gelatin silver photogram prints of glacier ice. Prints were made in a temporary darkroom in Alaska from melting glacier ice

DH: Would you say you have a spiritual approach to your art making? The resulting imagery in your work takes on a sublime, quietness to it. Yet, when the material is revealed as to what we are truly looking at, more comes into question about life, and the fragility of our planet and possibly ourselves.. In your series “Strata” I feel this takes place the strongest, can you also elaborate on how this series came to be?

SW: So, I’m not sure if I have a spiritual approach to the work, but the work allows me to access a kind of spirituality and a connection with all of life – animate and inanimate. I’m able to stand in wonder and I believe it’s a true privilege to be able to be moved by this world and consider more deeply our place within it. I was recently working with ice-cores drilled in Greenland and Antarctica at the National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility. It was profound to be faced with frozen water, one hundred thousand years old – a time machine accessed via tiny air bubbles locked into the layers of ice that existed long before history was a concept. To gather ice, recently calved from a receding glacier, hold it in my hands and watch it melt, helps me understand the impermanence of existence, the shapeshifting nature of water, the memory of the planet cradled in ice from a time when fossils lived as beings – and imagine a time long after our lives have been lived. I guess that feels pretty close to spirituality.

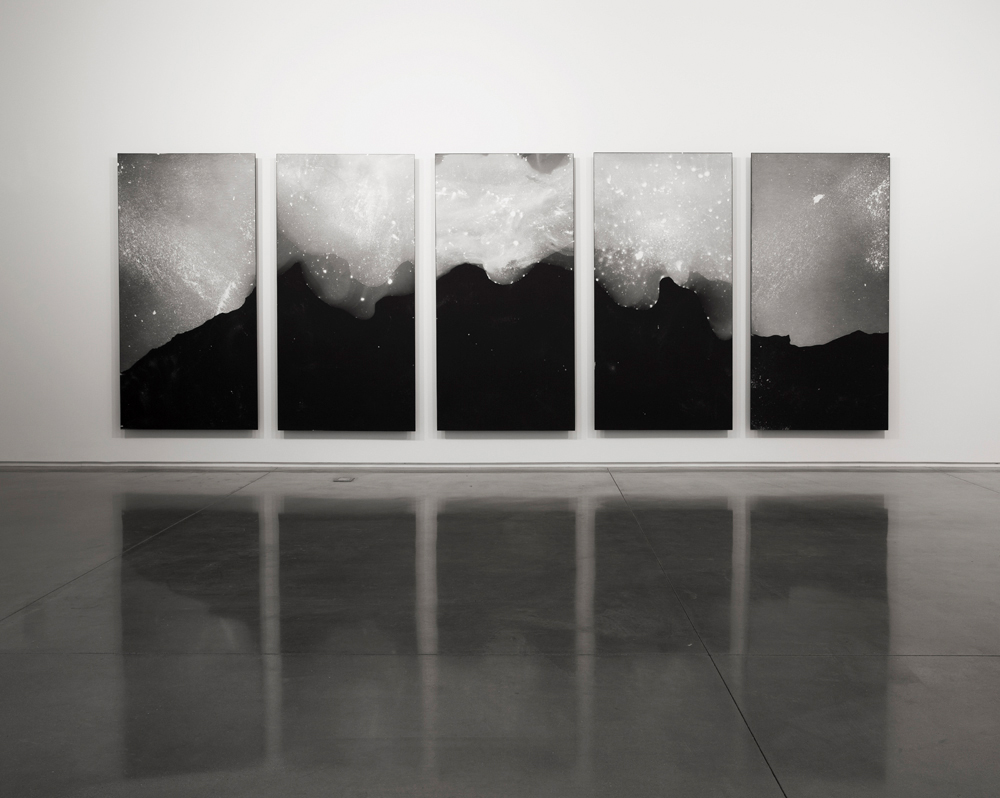

As to the Strata series, it began in Svalbard. I’d actually not registered the history of coal mining in the Arctic before participating in the Arctic Circle Residency. There was infrastructure still intact and mines visible at several spots including Pyramiden, an abandoned Russian Coal Mining town. I kind of tucked it away as I became more interested in the glacier ice – not just its extreme beauty but all of that hidden information held within its layers. After working in Alaska, with the ice, I’d been toting around the melt water. I spent six weeks in Pennsylvania as a visiting artist at Dickinson College. While there, I was reminded of my interest in coal and began collecting material from mines, grinding it and mixing the coal dust with melted glacier water. Taking the slurry into the darkroom, I began making photograms from the material and pairing those cameraless prints with photographs I’d made in areas that had been mined for coal in the Arctic. I was considering the macro/mirco connection and how dust in the hand can reference the larger universe. I was interested in coal and glacier ice as very different materials yet both formed through compression over time, both hold our planetary history in their layers and are tied together environmentally (in that coal fueled the industrial revolution which is impacting our climate today). The resulting work became a kind of fabricated or imagined landscape made from materials gathered in specific impacted environments.

DH: As someone who also uses the darkroom in their work, I am always most drawn to the unexpected results that can take place in that environment when printing. How does the role of chance and experimentation play into your work?

SW: I’ve always been interested in materiality and the latent image. Growing up, we had a darkroom at the house. I remember the magic of seeing an image appear out of nowhere under the red glow of the safelight. Making photograms is one of those basic elemental photographic processes which brings me back to a childlike playfulness filled with the surprise and discovery of how materials interact with light and are registered in silver. There’s an agency in materials that can transfer during the direct print process. The coal stains the paper, silt scratches the emulsion, melting glacier ice can move during exposure and leave the trace of motion – with its direct contact on the emulsion, and all of those events merge with the material presence of the print. It’s a mark, and also a memory of existence which has a level of unpredictability. I’m excited by the element of chance in the finishing of the work as well. The wax, paint, and metal dusts have a path of their own. Heated, they spread and move and I love that tension between control and acceptance.

© Shoshannah White Coal and Glacier Water Landscape, Five Panel Installation, 2017/2019, Scale: 84”x210” Pigment prints with mixed media on panel Original exists as photogram print made from melted glacier ice gathered in Prince William Sound and mixed with coal dust collected from Pennsylvania coal mines. Shown work was scanned, enlarged and worked with media.

DH: I love when you use the word “activated” in your artist statement for “Setting a Pulse”. Can you elaborate on why and how you used these magnetic materials? I feel I am always trying to do that, to activate a material, as if there is some other dormant energy or meaning wanting to be pulled from it that I can relate to.

SW: Beyond the mechanics and curiosity, I’m also thinking metaphorically: as in how we weather storms, how we’re attracted to and repelled from one another energetically or drawn to both beauty and destruction. The work in Setting a Pulse, explores invisible phenomena at play in our daily lives, through electromagnetic force. Photographs of lightning were captured over time during monsoon season in southeastern New Mexico. Some of the images are inverted and reference branches or tributaries and are paired with photograms created from materials which have been rearranged by magnetics. By exposing iron, earth, silt and rocks and activating them with magnets, invisible fields of energy are revealed through the dispersal of solid matter, leaving tracks or traces of their existence and movement. The final pieces can be exhibited as a kind of artifact of the event or sometimes scanned, enlarged and worked with gold, silver, mica, graphite — materials which were mined, forged or extracted and which themselves conduct energy. When applied to the image surface they can shine or become practically invisible, depending on conditions and variables of the space.

DH: Where do you see your work going next? Any new developments on processes or materials you could share yet?

SW: Ha! I seem to be in that awkward stage where I have several projects in the works but they’re shifting and changing as they take form. That said, I’m continuing work related to climate and am completely lit up by researching multiple forms of intelligence from plant communication to bacteria.

Daniel, thank you so much for such insightful consideration of my work and for all of these thoughtful questions. It’s been such a treat.

© Shoshannah White, Coal and glacier Water#9, 2017, Scale: 10”x8” Gelatin silver photogram prints of melted glacier ice gathered in Prince William Sound, Alaska mixed with coal dust collected from Pennsylvania coal mine.

Daniel Hojnacki recently received his M.F.A from the University of New Mexico in 2022. Hojnacki’s practice uses experimental techniques in photography as a way to be a quiet mindful observer within the world. His work incorporates material that pushes against traditional approaches to the photographic printmaking process. Creating drawings using the cliché verre printing technique by applying smoke soot to glass. Daniel records the body and the natural world captured as subtle and fleeting textural gestures.

Daniel is a recipient of several awards and residencies including The Penumbra Work Space Artist In Residence, LATITUDE Artist in Resident in Feb 2023, Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention, The Patrick Nagatani Photography Scholarship, The Phyllis Muth Arts Award. He has exhibited work at the Museum of Contemporary Photography and The Chicago Cultural Center. Daniel has hosted public workshops and lectures with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the Smart Museum of Art. His work has been featured in Phases Magazine, Aint-Bad and Southwest Contemporary Magazine’s fall issue “Inhale/ Exhale”.

Follow Daniel Hojnacki on Instagram: @d_hojnacki

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Mehrdad Mirzaie in Conversation with Liz CohenSeptember 4th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Elizabeth Hopkins in Conversation with Nicholas MuellnerAugust 21st, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Cléo Sương Mai Richez in Conversation with Shala MillerAugust 20th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Emma Ressel in Conversation with Tanya MarcuseAugust 19th, 2025