Photographers on Photographers: Evan Baden, Aaron Canipe and Sara J. Winston

Conversation and collaboration are among the things I enjoy most when making a book. In the case of my current endeavor, Shades, available this fall from Push Pull Editions based in Corvallis, Oregon, I’ve had the pleasure of communicating regularly with friends and collaborators on the project: Evan Baden, Aaron Canipe, and Nat Ward. Today Evan, Aaron and I discuss some qualities of the book, how it began and how it’s going.

Evan Baden: In 2020, during the height of the pandemic–when I couldn’t be out photographing–I decided to start a photobook press called Push Pull Editions. Books primarily feature photographers and image-makers that operate in a documentary fashion. One of the main goals of Push Pull is to eliminate the “pay-to-play” system that so many presses operate within. My goal is to produce small editions of work I believe in, pre-sell the edition to fund the materials, sidestep distribution models, give books to the artists, and leave none of the participants in debt.

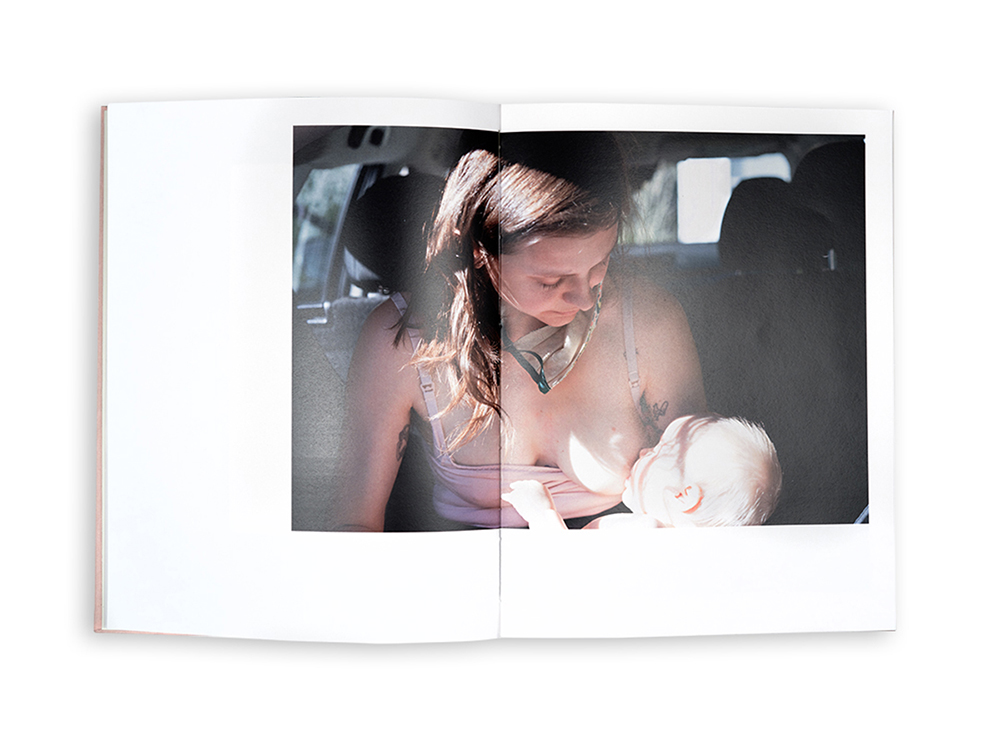

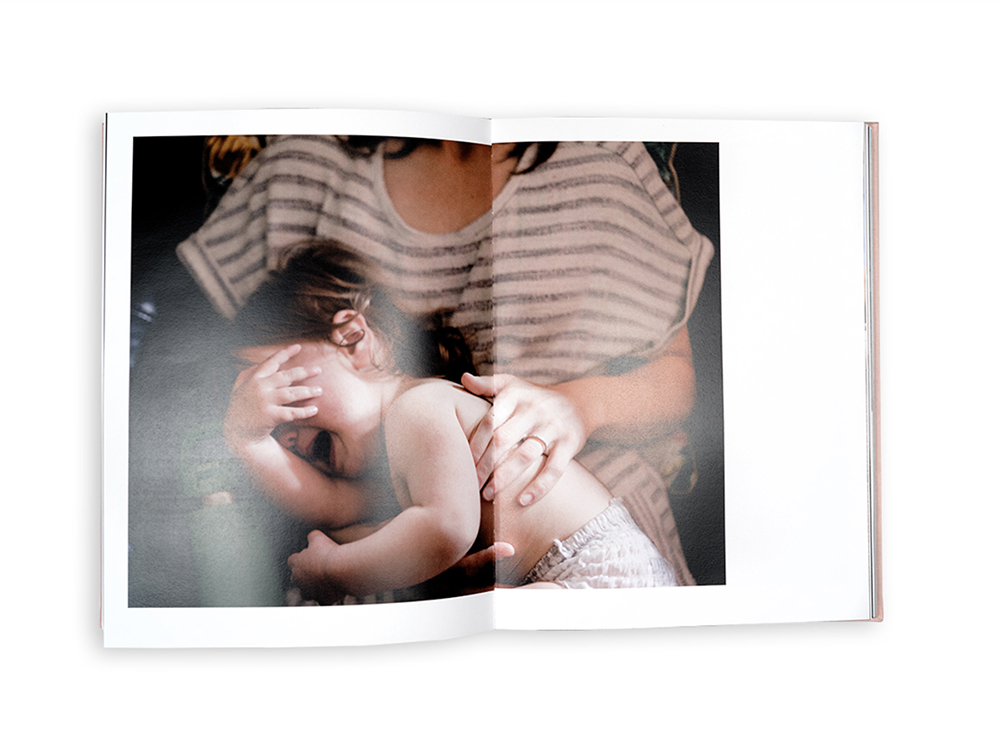

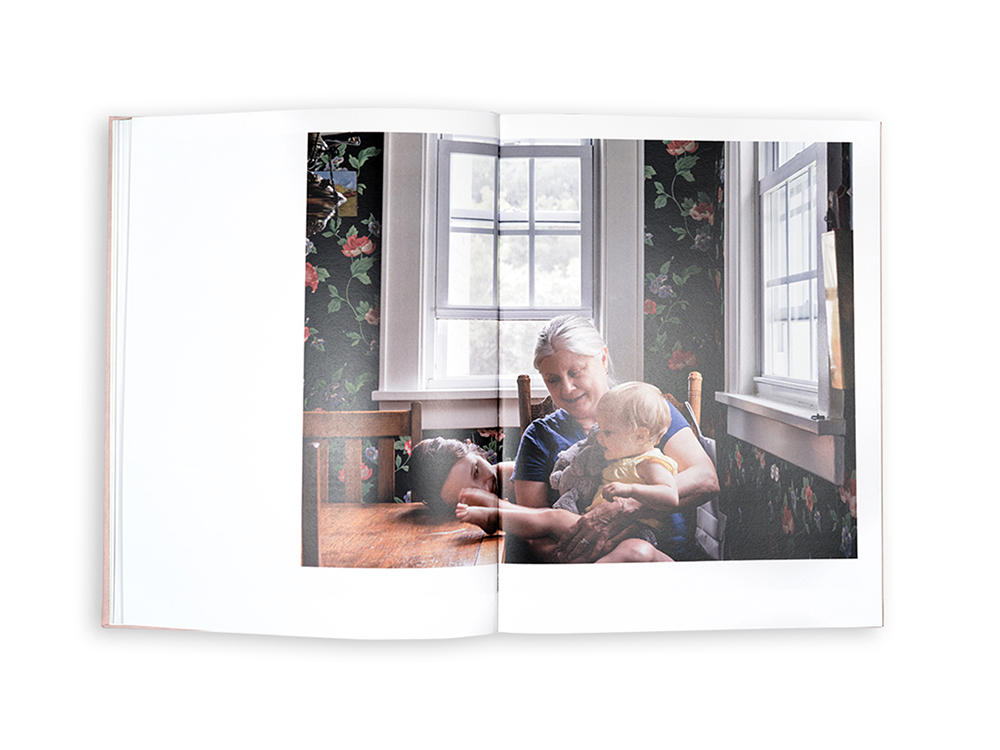

The first book I put out was Wendel White’s Schools for the Colored, which I produced in the summer of 2022. Knowing that I needed to have multiple projects lined up in order to sustain my press, I began looking for additional projects. Sara, whom I attended graduate school with at Columbia College Chicago and whom I’ve never thought of as a maker of portraits, had begun posting images of herself, her daughter, and her mother. The starkness of some of these images was a real draw to me. There is beauty and joy in parenting but it is accompanied by unimaginable stress, pain, and sadness, especially in the middle of a pandemic. I felt Sara’s images carried a truthfulness that I don’t often recognize in much of the work I see made about parenthood. I approached Sara to see how developed the work was and if she might be interested in working on a book together. She came to our meeting (via Zoom, of course) with a counter proposal. Sara had been engaged in a visual dialog for several years with Aaron Canipe at A New Nothing and she thought that it would be interesting to publish that conversation. I was interested in the fact they both had daughters about the same age and I thought it would be interesting to see those different, intimate, and intersecting perspectives bound together. I also have a daughter the same age and I thought that made the collaboration especially poignant as I was seeing my own experiences in the images Aaron and Sara were making. So here we are now, with a book about to go into production.

This book isn’t a direct translation of the conversation both of you were having, but I am curious how you began the dialog and how it evolved after becoming parents?

Aaron Canipe: Sara and I go back a number of years to our undergraduate days at the Corcoran College of Art + Design in Washington, DC. Sara’s initial outreach to me many years after college to begin a fun, side project with back and forth, conversational images on A New Nothing was thrilling. The visual dialog reintroduced the pleasure in photography I had lost in my post-MFA slump. Later when we both had children, it helped knowing that Sara and I were dealing with similar problems and joys of being parents and I think that shows in the photos. After becoming a parent, the work in SHADES became not only a side project, it became my project. My personal approach to art-making radically changed; it’s always been about family and place, but now it is wildly closer.

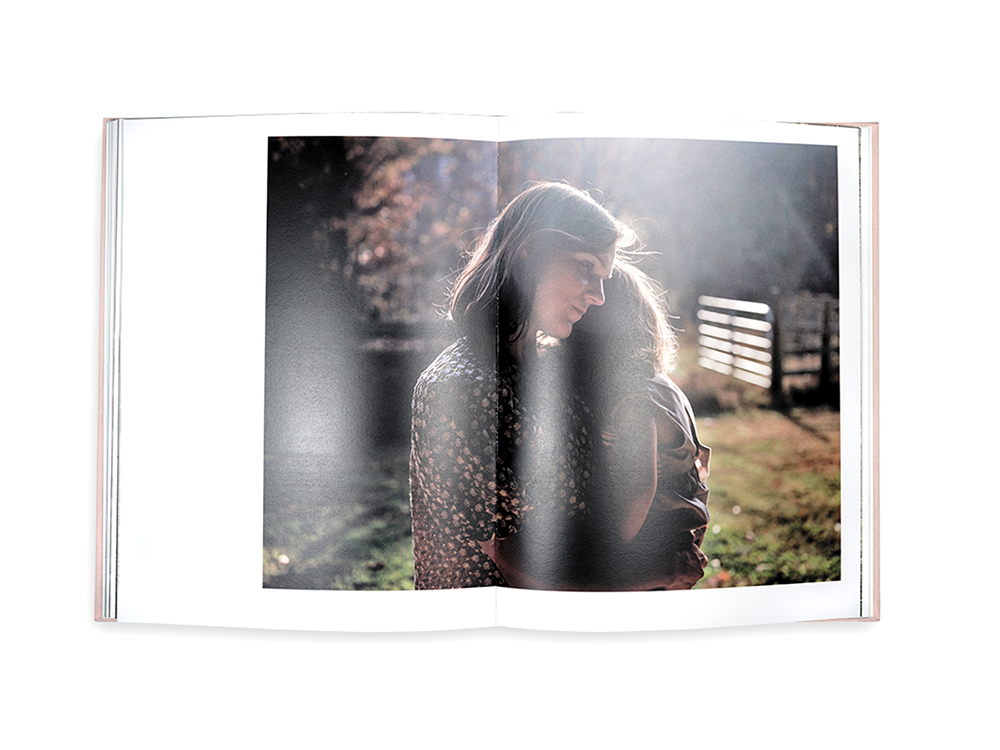

Sara J. Winston: I remember a conversation Aaron and I had via text message while I was uploading the image I posted on 5/12/19. We always text one another when we put up a new photograph. His text response was to enthusiastically share that he and his wife were also expecting. His photographic response, 5/20/19, shows Meredith pregnant. That visual volley is included in the book as the frontispiece. I’m very pleased with that editorial decision, Evan. I feel like in our conversation on A New Nothing, that exchange between us changed the tone of things. Of everything, actually.

EB: The act of having a child is one of those cataclysmic events that upends routines, and while it can be limiting in many respects, also opens one up to a whole new understanding of being and relationships. I feel for a lot of artists working, especially making work that is personal in nature, the work shifts to try and understand those new relationships. I find it serendipitous that you were both moving through those shifts in parallel, and that really drew me to the work. I do love that the start of the book features the two main subjects of the book in a state of change, not yet parents but also no longer who they used to be. I really liked this as a preface to what the reader was about to encounter.

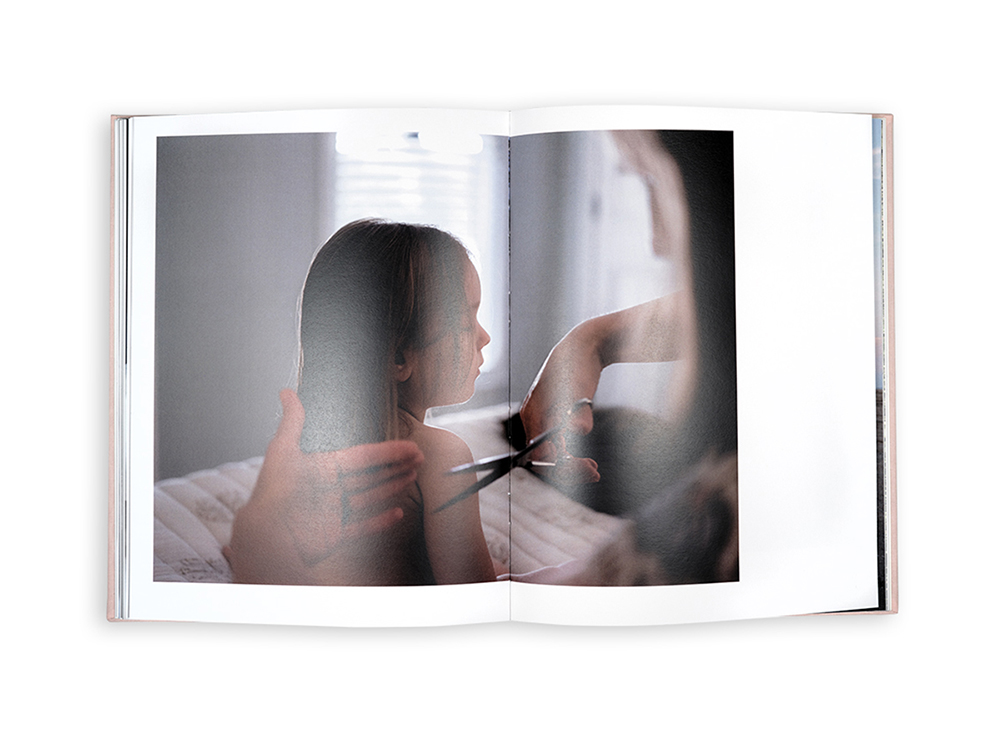

I never felt this set of images should be filtered out to “artist A” and “artist B”. In designing the book I was really interested in intertwining the images, in a sense merging the work. I am wondering how you both feel about that mix, and what you think it does to the overall feel of images you were making separately? Or perhaps has it changed how you think about making work moving forward?

AC: You’re right, Evan, I loved the serendipity that only comes with photography. The sequences you made in the book really bring that to light in a way that could not be done if it was filtered out didactically in the way you described. The mix makes the book a much more intentional thing and reveals more than I knew about our lives: how the movement of a dress looks like a handful of thrown grass or how grandparents carry a body through the air just like jumping off a bed. These are connections best brought to the reader through book form.

SJW: I’m curious what it was like for you to design the book, Evan? Both the regular and Collector’s Edition? While we chimed in here and there, you had a lot of free rein, as well as our trust in your vision. To me, your role in the making of the thing is nearly equal to that of being an author.

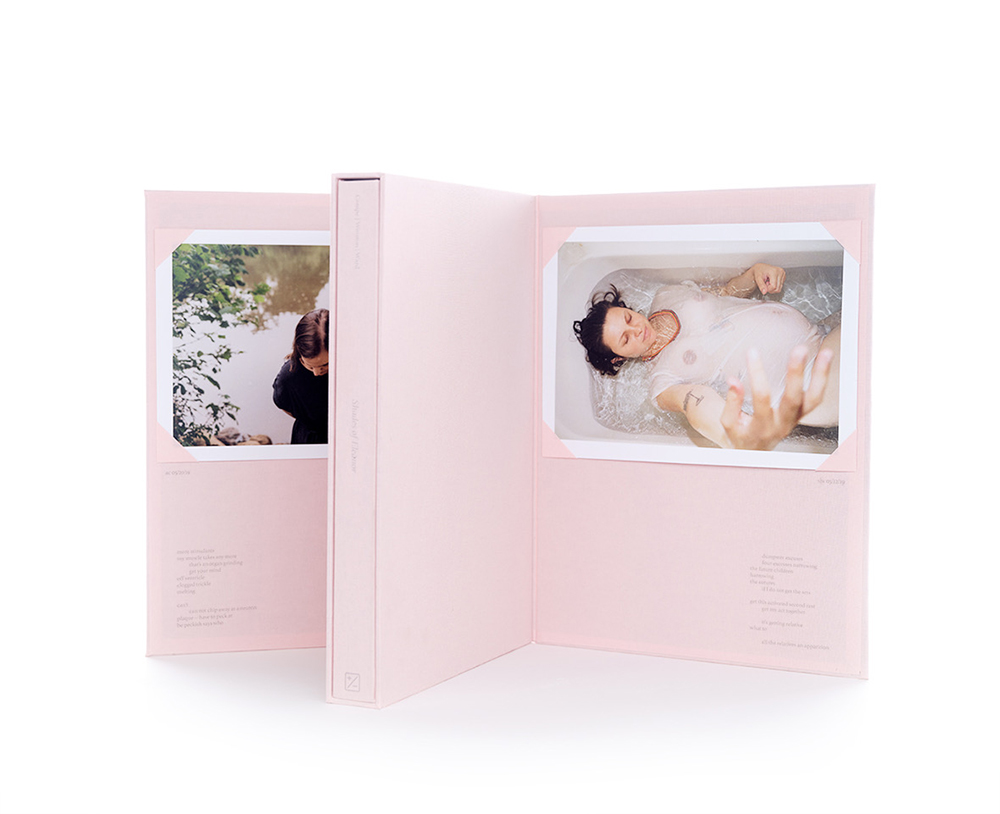

Collector’s Edition of Shades, © Sara J. Winston, Aaron Canipe, words by Nat Ward, Push Pull Editions 2023

EB: I think that when it comes to designing a book of another artist’s work, in this case more than one, it is by necessity a collaborative effort. There are a host of concerns that need to be addressed when thinking about book design like this: the work itself, the viewer, and of course the artist[s]. First, and maybe most importantly, is finding a way to consolidate, sequence, and translate the work in a way that both stays true to the original vision and intention of the artist[s] while at the same time expanding and adding to the overall impact. Second, keeping the viewer engaged with the work throughout the book. In a book like this, that spans 70-some images across 144 pages, I am always looking to make sure there is no repetition. That means no repetition in spread layout, size, or subject (all in addition to watching out for paper stock changes and centerfold thread). This keeps the work undulating and gives the viewer the feeling they’re always seeing something new. Finally, none of this matters if the artists themselves don’t feel that the book holds to the same core values as the original. However, what I often find successful is for the artist to hand over all the control, at least in the beginning, and let someone outside the work reinterpret it. I often find that we as artists, when making, become too intertwined with the work and sometimes letting go breathes new life into what has been created. I am always nervous for the artists I’m working with to see the first dummies.

The standard Collector’s Editions I usually see out in the world simply come with a bare signed print, but I feel this is where I really get to make something of my own, something that steps outside the book itself. I love the notion of every Collector’s Edition being a little different (in this case coming with a unique set of prints) and I love finding new ways to encase the book that relates to the work but also elevates the book as an object in itself. It’s also important to me to keep those Editions in an affordable space for supporters who really want to help the project in an extra way.

In terms of being part of the authorial group, I’m not sure I’m all the way there. I feel a great design can bring new understanding and a new shape to the work, many times even for the artist, but it still relies on the work existing first. I would equate what I am doing as more of an editor. But luckily for me, since I alone am the whole press, that name gets to be right on the spine as well.

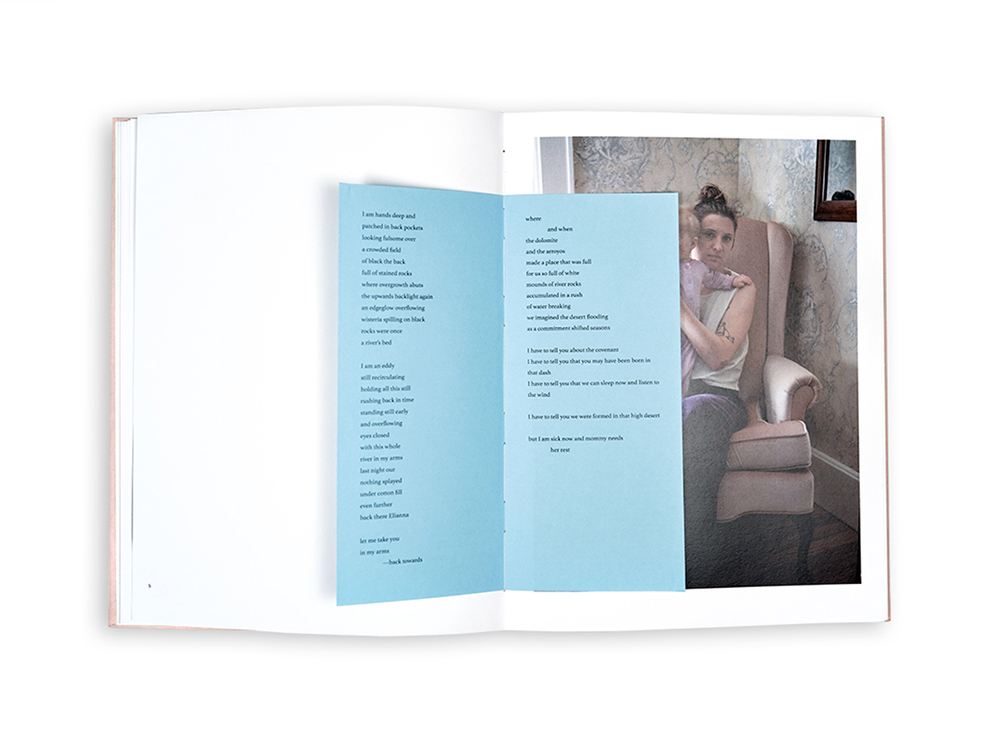

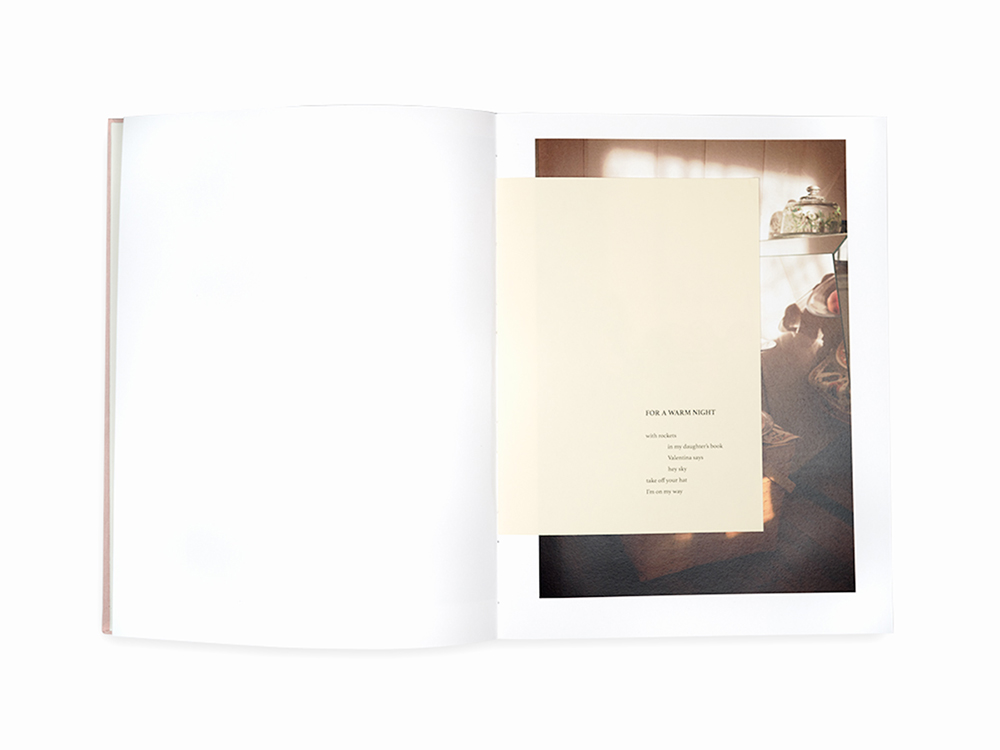

SJW: Interesting. For me, generally, the idea of the authorial role transcends whether a name appears on the spine. Different publishers I’ve worked with have different feelings on this topic. Each time the level of collaboration on design and image sequencing has varied. I wondered about your feelings on authorship, Evan, particularly because of how the photographs of Aaron and my daughters and the writing by Nat Ward might be reminiscent of your parallel experiences with your child. And with all of our parenting experiences happening simultaneously, all of us with children who are about the same age, how those similar experiences we’ve all had that appear in the images might impact your design choices. Like the decision to print Nat’s writing on different pastel color pages, for example.

AC: Evan, you just mentioned a little bit the difficulty of collaboration as well as having a young daughter as well. Sara, there’s some obvious directorial modes you take in terms of collaborating for photographs with your own mother and daughter. From a fellow busy parent and perhaps others, a question for you both: How do you do it? Sara, photographically, what is your approach to capturing your favorite images from the book? And Evan, what of juggling your practice, your university teaching load, and your family?

SJW: Many of my favorite images, the intergenerational photographs with my mom and daughter, were made while my family was living with my parents at the height of uncertainty during the Covid pandemic in 2020. My child was young, only six months old when we moved back into my childhood home. She wasn’t walking yet, which in plain terms meant life with a child was still tethered to how and when the adults moved around the house and its yard. We lived in the house together from February through mid-August of 2020. During that period I made at least one portrait a day of the three generations. It brought us closer together. It was usually fun, occasionally impossible, but I pushed through everyday with the camera. Time felt like it moved impossibly slow in that period of parenting and pandemic, but now those days feel like a lifetime ago.

EB: I would say that my daughter has been an inspiration in ways that I never considered. When it comes to materials, I find myself wanting to incorporate some of the things I buy for her—markers, colored paper, coloring books—into what I am making for others. In the case of Shades, when thinking about the incorporation of Nat’s text, the colored paper that she uses (or at least a reference to that) seemed entirely appropriate. Something that could feel both childlike and elegant.

I still think of myself as primarily a photographer, but the type of project I like to work on was not possible with an infant. Then COVID hit, which limited the possible things I could do even further. I’ve always envied artists that can make work where they are, and it felt like starting the book press (which had been in the back of my mind for a long time) was a way of being able to continue working. I also have to say, conversations with both of you felt closer because I feel like there is a shared struggle for those that had very small children during COVID. We all share in the impossibility of trying to be parents, partners, full-time employees, artists, during a pandemic, while mostly failing to maintain balance. For myself, I often look back at the end of a project and am never quite sure how I got it finished. Since my daughter was born, it seems, I have almost no memory of the things I do.

I think that Nat’s text also provides that same type of feeling. To me, they feel like phantoms of memory, little wisps of things that one is aware has actually happened, but can’t quite remember the details. That aspect of the text really related to my own experience and I think that having those snippets filtered amongst the images gives a nice fleeting feeling to the book. The title is a lovely reference to that as well. I think the challenge of titling an unpredictable body of work (very much still in motion for Sara and Aaron) in a way that brings three different artists together is tricky, and Shades with its different interpretations works well. I know each of us may relate to a different meaning of the word, but I see it as just a trace, or a remnant. And I find it interesting in relation to a set of images, because those images can never quite catch the rawness in the moment they capture.

Evan Baden is an acclaimed practitioner of photography. He has had numerous international exhibitions, publications, and his work is held in a number of important public collections. Evan is the founder and publisher of Push Pull Editions. He has been teaching photography and bookmaking/design at Oregon State University since 2015.

Follow Evan on Instagram at @evanbaden

Aaron Canipe is a photographer and designer based in Mebane, North Carolina. Deeply-rooted in family and place in the North Carolina piedmont, his photographs have been exhibited throughout the Southeast and are included in collections at Telfair Museums collection, The Do Good Fund, The Archive of Documentary Arts, among others.

Follow Aaron on Instagram at @aaroncanipe

Sara J. Winston is an artist based in the Hudson Valley region of New York, USA. She works with photographs, text, and the book form to describe and respond to chronic illness and its ongoing impact on her body, mind, family, and memory. Sara is the author of several photobooks, among them Shades (collaboration with Aaron Canipe & Nat Ward; Push Pull Editions, 2023), A Lick and a Promise (Candor Arts, 2017) and Homesick (Zatara Press, 2015). Sara is the Photography Program Coordinator at Bard College; on the faculty of the Penumbra Foundation Long Term Photobook Program; Adjunct Professor at Syracuse University; a contributor to Lenscratch; and a member of Storm King Art Center‘s Accessibility Advisory Group. On June 29, 2023, her long-term project about multiple sclerosis care, Our body is a clock, was adapted and published as an op-ed in the New York Times, titled ‘My body is a clock’: The Private Life of Chronic Care.

Follow Sara on Instagram at @sarajwinston

Push Pull Editions is an independent book press located in Corvallis, Oregon that focuses on publishing photographic books with a documentary focus in small edition runs of 100-250 copies. All design and production is completed by Evan Baden.

Follow Push Pull Editions on Instagram at @pushpulleditions

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Andrew Lichtenstein: This Short Life: Photojournalism as Resistance and ConcernDecember 21st, 2025

-

Martin Stranka: All My StrangersDecember 14th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025