Christine Back: PV Revisited

This week we are looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Christine Back and I discuss PV Revisited.

Christine Back is a New Jersey-based photographer and educator who grew up at the Jersey Shore. The seasonal nature of her home town instilled in her a keen interest in the effect of impermanence on how we value each other and the places we live, work, and play. Exploring George Santayana’s idea that “repetition is the only form of permanence that nature can achieve”, she may return to the same composition daily for a year or after decades away to sort out what is new, what remains, and what is forever gone.

She holds a BFA and an MAT from Montclair State University and has been teaching high school photography for twenty-five years. She is the recipient of a 2023 New Jersey State Council on the Arts Individual Artists Photography Fellowship and several Geraldine R. Dodge Grants for teaching artists. Her work has appeared in The Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday Magazine, New Jersey Monthly Magazine, and Vision Magazine in China. Her work has been shown in New York, New Jersey and internationally.

PV Revisited

I like a good cover song. They seem to ground the performers, give them some reassurance that they are part of something bigger than themselves. I love noticing which original sounds remain and which others get obliterated when the present just can’t help but to assert itself.

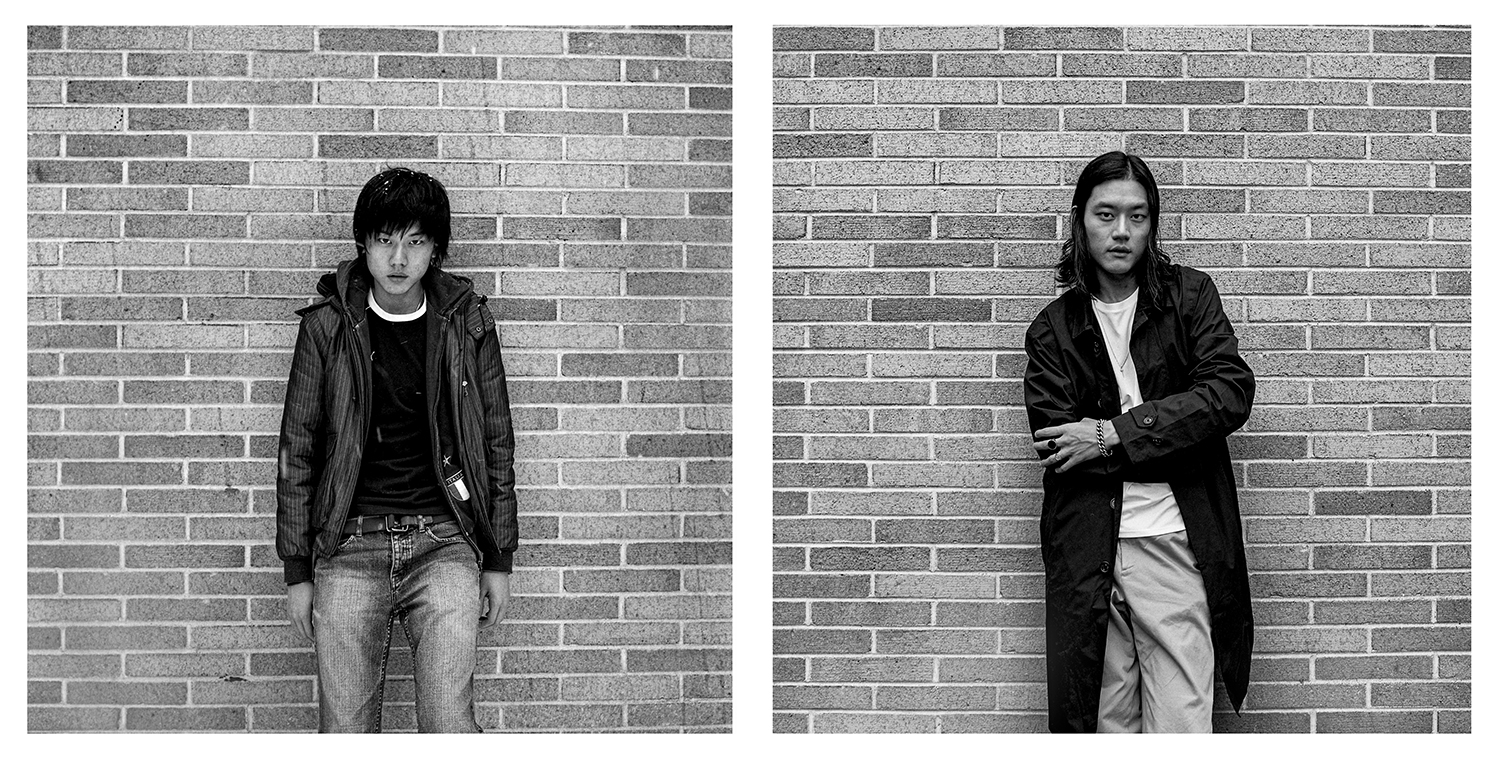

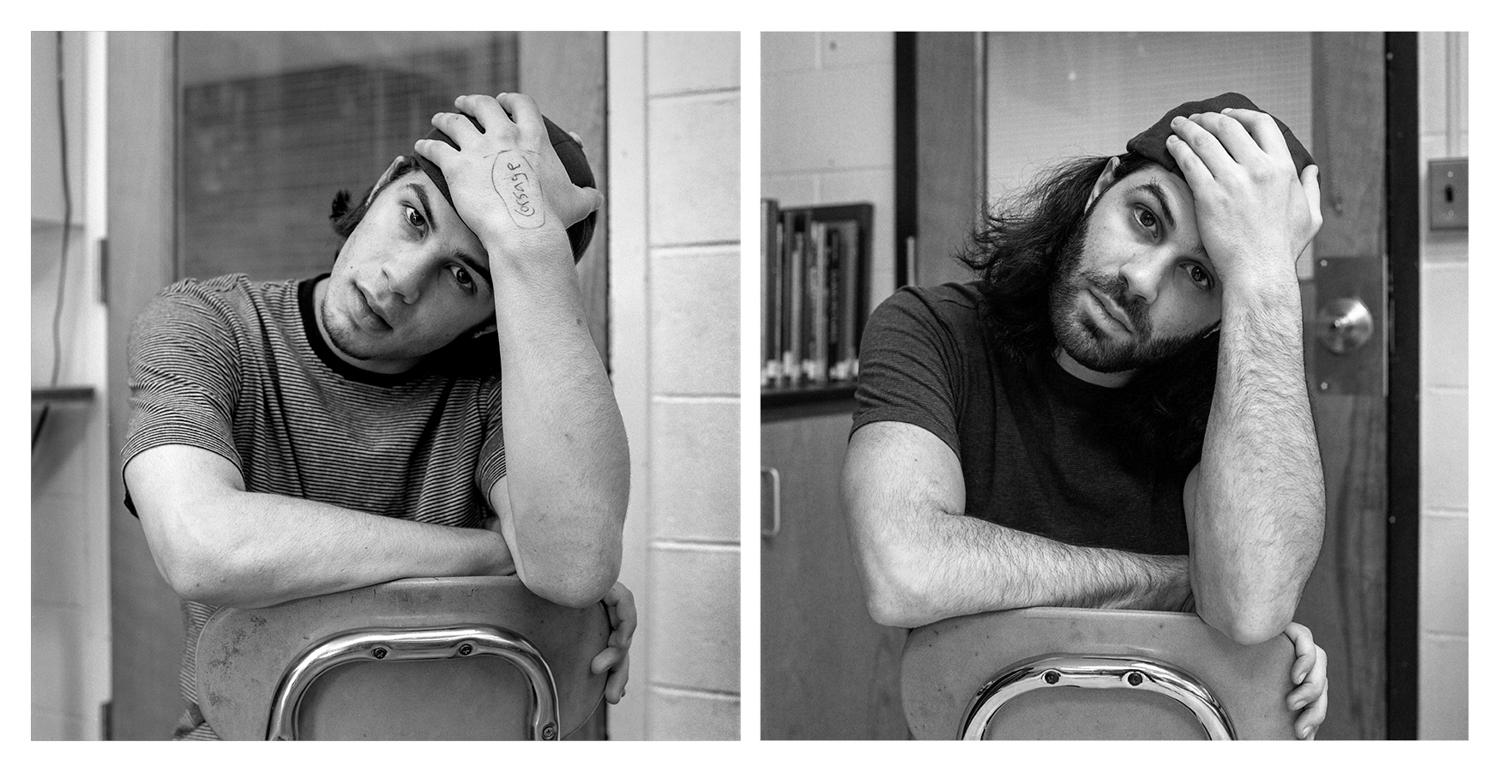

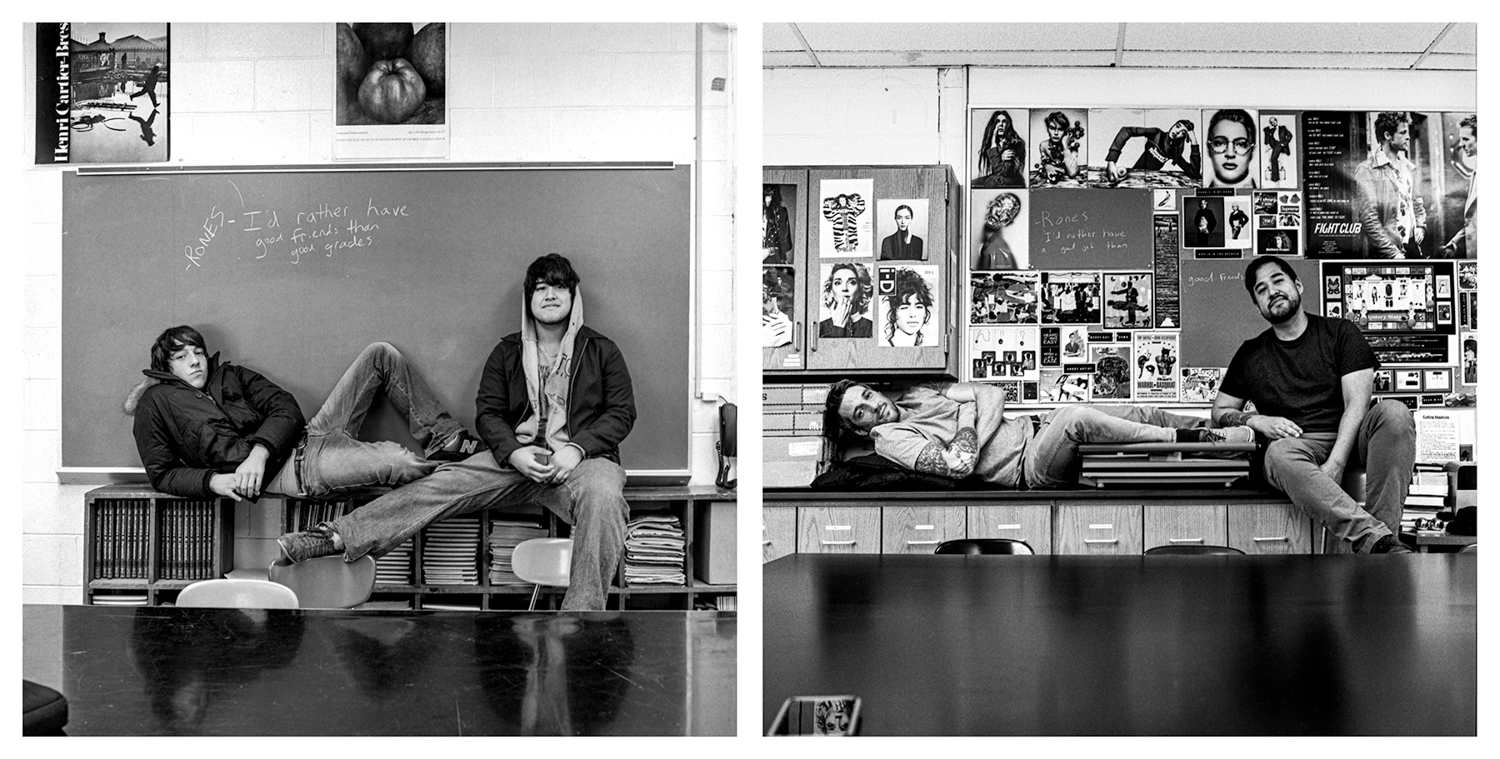

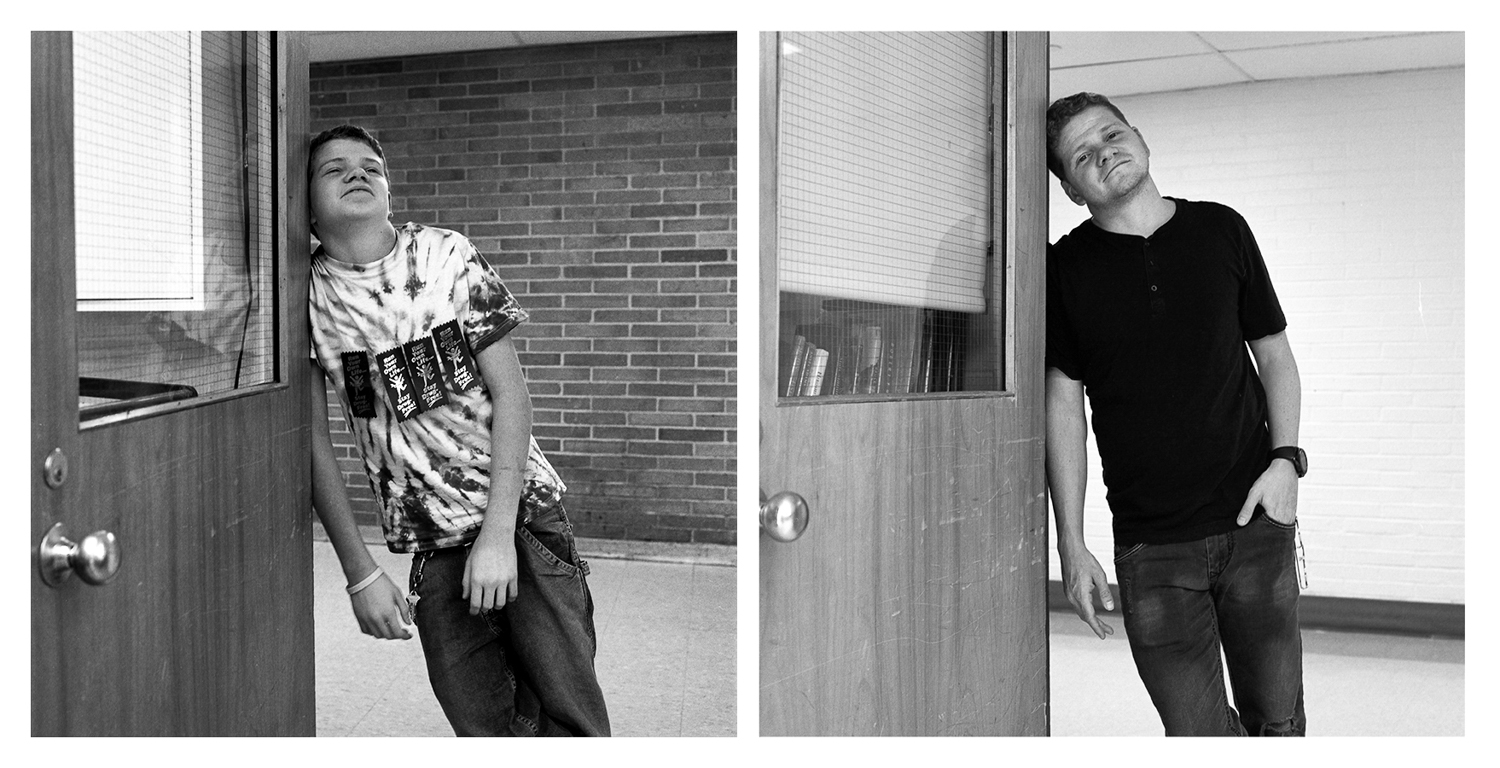

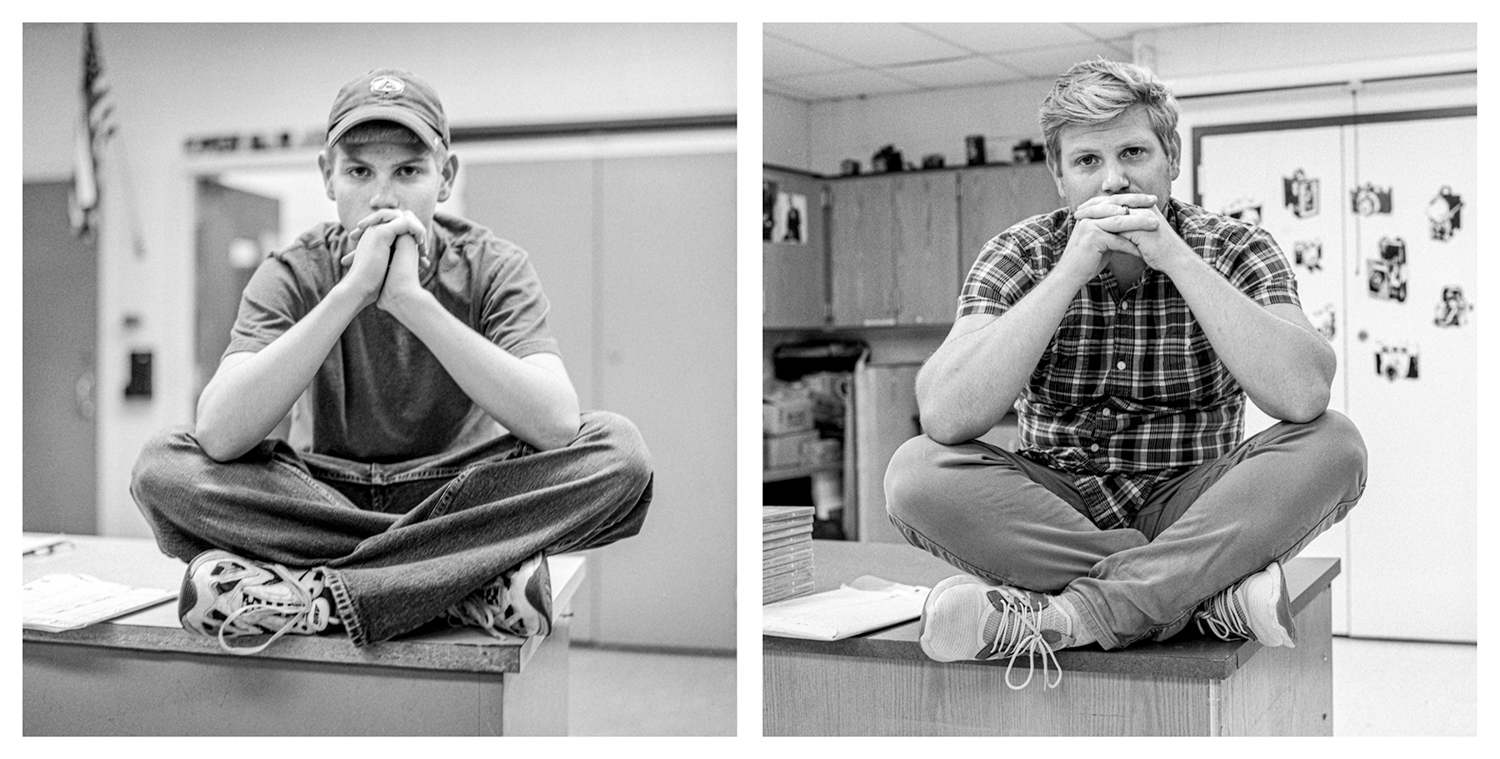

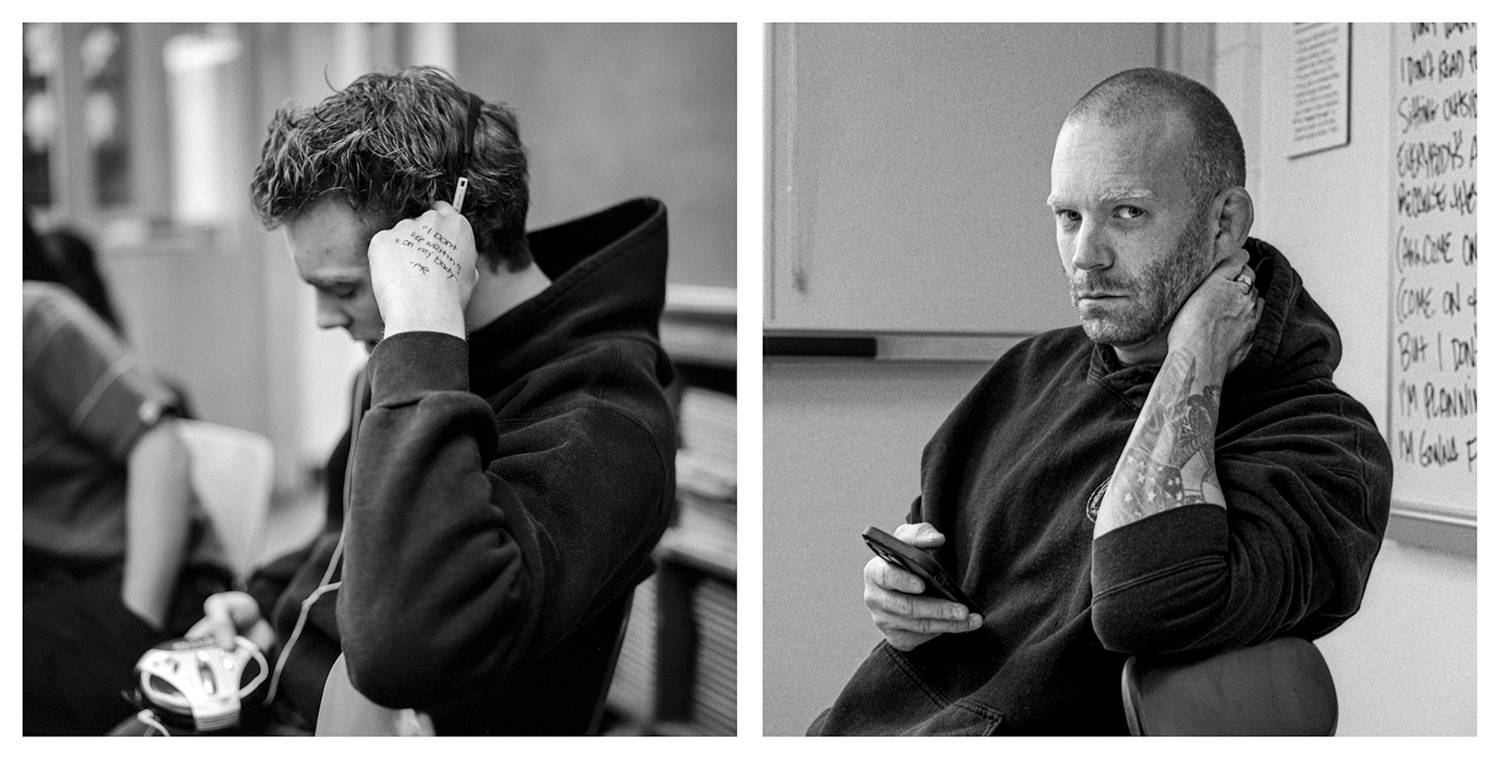

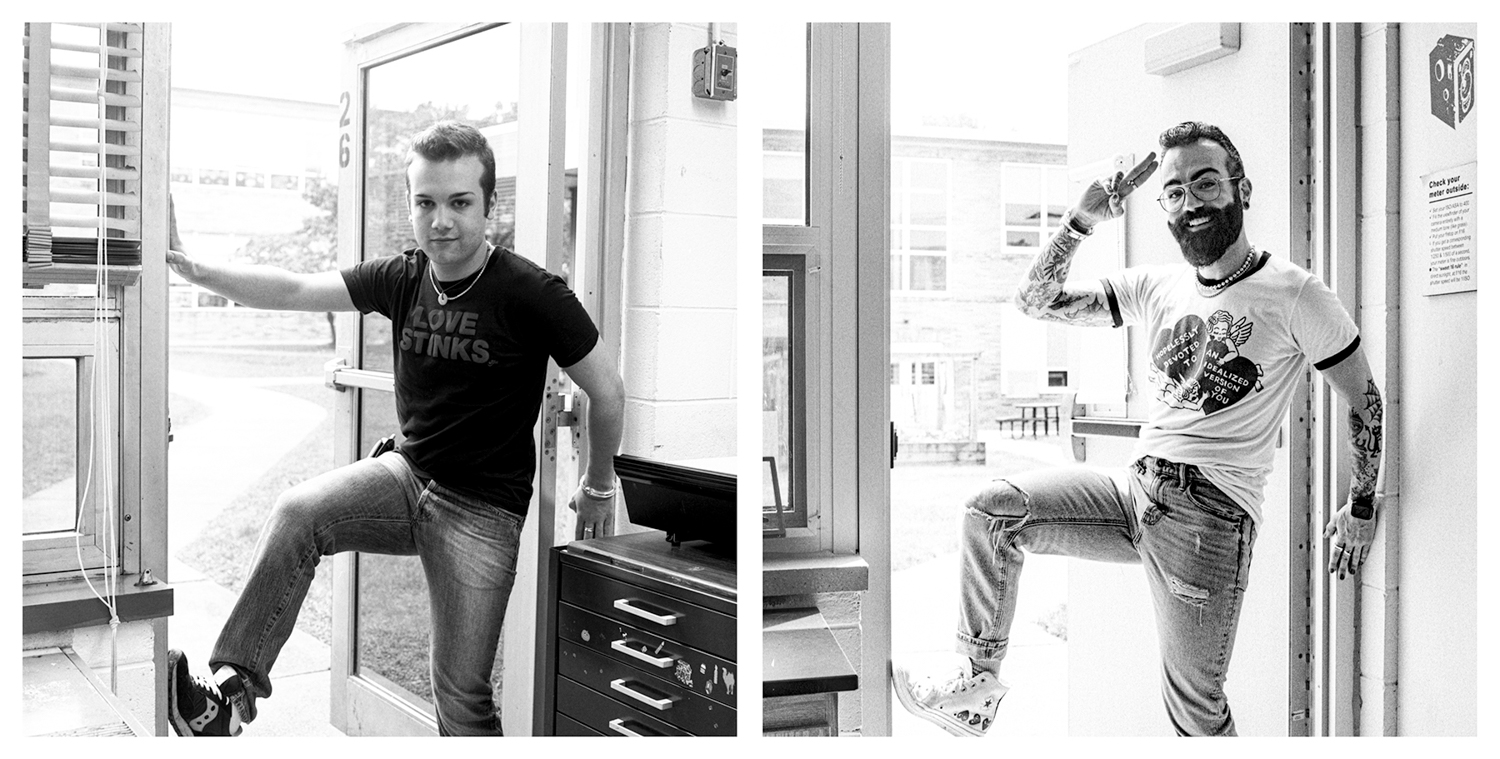

About five years ago, I started recreating photographs I made of my high school photography students back in the ‘00s. I was covering my own songs, getting back to my roots. It had been fifteen, even twenty years since I’d seen some of these people. They were in their thirties, roughly the same age I was when I taught them. Every inch of my classroom has changed except for one door, but with each session, I did my best to recreate those little details of shape, texture, and tone. I struggled to schedule shoots when the sun crept in the right window at the right time and scavenged old chairs from custodial closets.

I had shot about ten sessions when shooting got put on hold by the pandemic. While in lockdown, I sent the work out into the world and gained some outside support. This year, I’ve started shooting again, finding alumni mostly through word of mouth. A friend shows another friend the project and I hear that they want in. I send them scans of the originals and write to them about school security protocol. We spend weeks trying to set up a time and I get nervous that I’m just annoying them. Then they finally walk through the door, smile, and the weeks of worry fall away.

I am always deeply moved to find that they too have put thought into the details on their end. They come with bags of clothing changes and often stay for hours. During each session, there is a point where we are struggling to get the pose and composition correct and are humbled by the impossibility of ever getting it perfect. We decide it is close enough and spend the rest of the time talking in hopes of finding a moment of emotional connection to their teenage self.

This year, I had my current students recreate album covers and historical photographs to introduce them to this oddly freeing form of play.

I also shared the growing series of alumni diptychs and many wished they could have gone to high school before cell phones, laptops, and social media. They settled for posing in front of my moldy, taped up Hasselblad. After the valued, yet frustrating experience of being beholden to source images, I found the freedom of shooting without those constraints immensely refreshing. I had to laugh though when most of them said they’d be back in ten years for me to shoot them again. I don’t know if I’ll be around that long, but I’ll try to hang in there until they get out of college or the army.

Daniel George: So, this series really began in the 2000’s with the first photographs that you made of these high-schoolers. Could you talk more about those early motivations.” Also, you mention a “longing for analog photography,” in your artist statement, but what else encouraged you to revisit these portraits?

Christine Back: I think what I actually longed for was the state of mind I associated with shooting portraits through a waist level viewfinder. In college, I shot with either 35mm or 4 X 5 cameras. Then sometime in the early ‘90s, a friend in Asbury Park loaned me a twin lens Yashica. Shooting in that place at that time with that camera was an immediately transcendent experience. I think it was brought on by the flatness of the space , the closeness of the humid air, and the way that viewfinder allowed me to stay face-to-face with these mutually curious strangers. I always left that place floating on air.

Several years later, I found myself teaching high school photography full time with no intentions of shooting on the job. But then, I got assigned “quiet study” duty in a room that also housed the in-school suspension students and the xerox copiers. It was nuts and I started bringing my Hasselblad with a waist-level finder just to help me get a grip on the situation.

Soon, I started to bring my camera to my actual classes on half-days, Halloween, when the skies threatened snowfall, and the very last weeks of the year. Days when the kids were most “them”.

Then one year, they gave the kids laptops and I found myself talking to the tops of their heads all day. For about a decade, we were all just “doing school” and at home I was “doing life”. I started thinking about making the “now” pictures when my dissatisfaction finally outweighed my fears of starting the project. I had a gut feeling that this project would be my way back to that feeling.

DG: One aspect of this work that caught (and continues to hold) my attention was the idea of the younger version looking forward and the older version looking back. I imagine this generated some interesting conversations during the most recent image-making sessions. In general, what were those discussions like?

CB: I do ask the teenagers to look directly into the lens and think about how someday they will be an adult and their teenage eyes will be looking right back at them from the past. It’s so intense I sometimes look away for a frame or two so they can do it without me in the middle of it. In general, the conversations are an exchange of key memories during which they remember who they were through my memories and I through theirs. It’s funny how they have the actual facts of my life incorrect, yet they do get the gist of it alright.

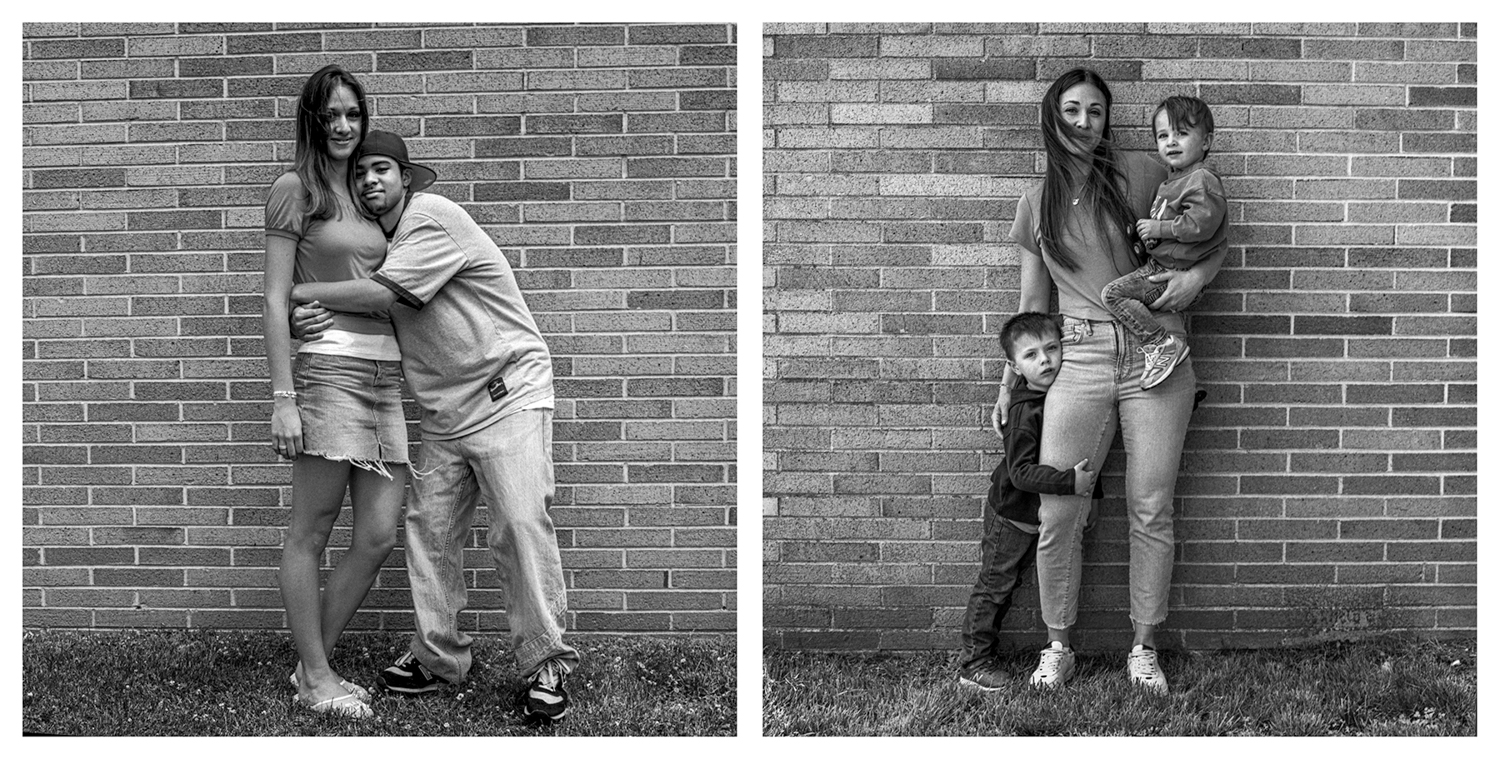

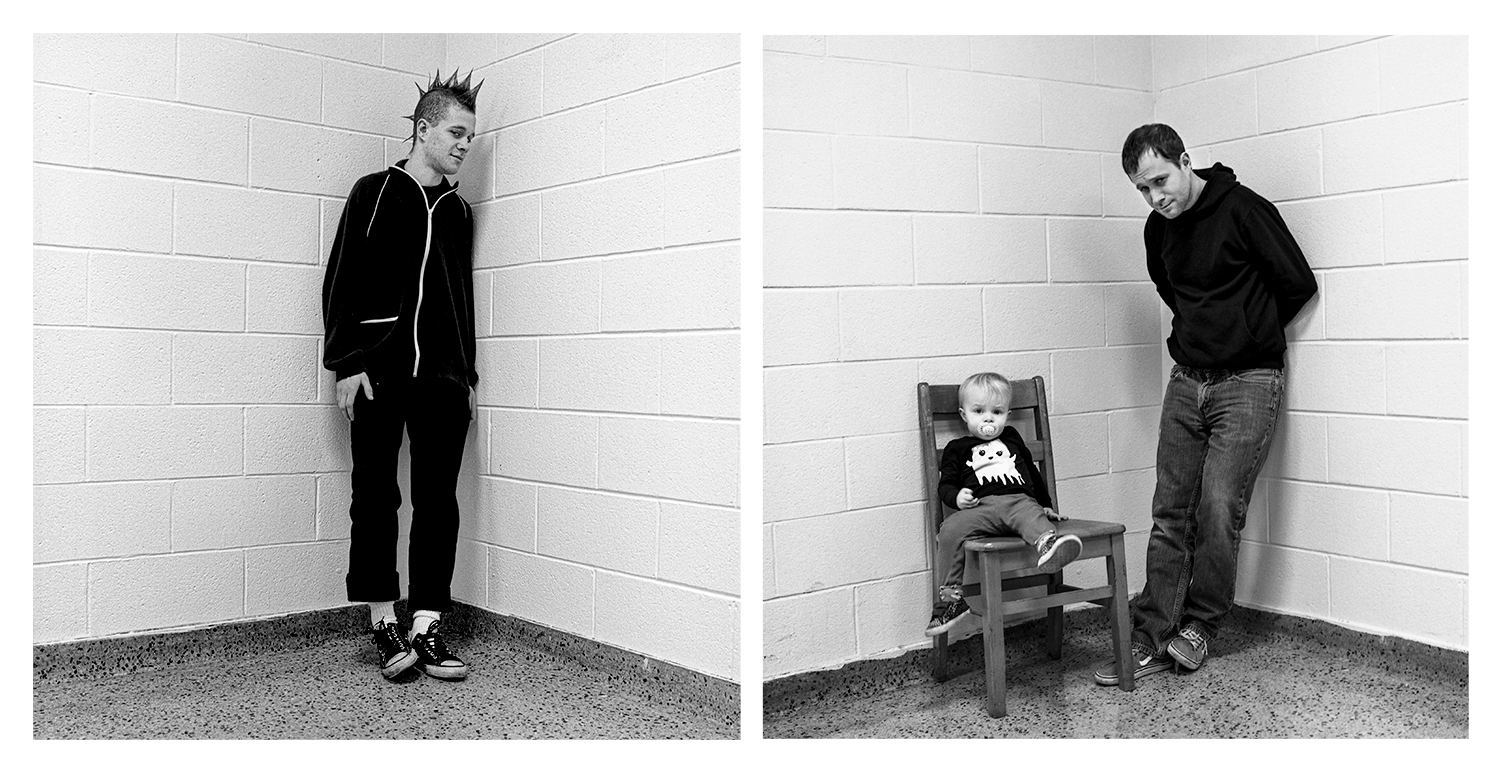

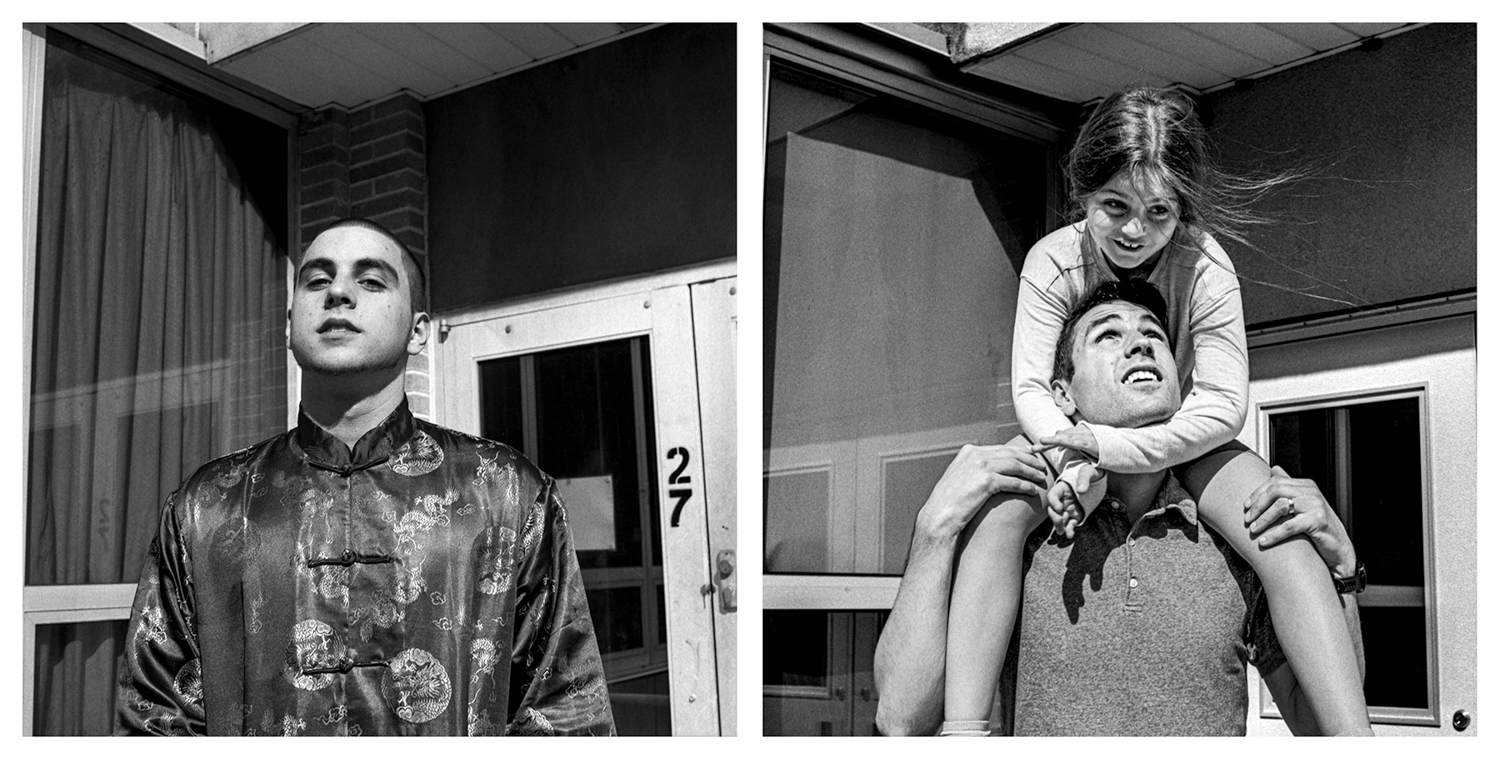

DG: Looking at the photos, there seems to be a sort of sub-theme of relationships—with peers in the frame being replaced by family members, or simply the addition of another individual that wasn’t in there initially. I’d like to hear your thoughts on this.

CB: The thing I love most about my job is watching kids make unexpected, even unlikely friendships. That light in their eyes and the smiles they fail to stifle are the fuel that keeps the class moving. I actually do have many pictures of kids together but I haven’t been able to schedule the correct pairings or groups just yet. The project has really only just begun. I honestly started submitting the work so I’d have fresh stories about how artists submit their work and deal with rejection. I do have some of those but now I also have some about facing the threat of success.

The first family member pictures just happened because someone brought their wife and baby so I could meet them. Then I saw how much their kids adored them and couldn’t resist bringing them into the shoot.

DG: In your biography, you write that you are interested in “the effect of impermanence on how we value each other and the places we live, work, learn, and play” and how this was brought about by the seasonal nature of your hometown. In what ways do you see this evident in PV Revisited?

CB: I was a fairly introverted kid. I barely ever left my own yard partly for fear of starting something I didn’t want to have to finish. When I was in high school, my family moved to Cape May, the very southern tip of New Jersey. Back then, it was jam packed in July and August and a ghost town by Labor Day. I began to take more social risks in the summer because I knew I could count on everyone leaving town and I had those long winters to recharge my batteries. But sometimes it hit me really hard when those fast friends left. I learned to feel those connections as deeply as I could while they lasted.

That sensitivity to time definitely followed me into the classroom. I would nudge the class clowns to engage the shy kids just a bit. Get them to crack a smile and move on. Circle back tomorrow. It is much harder these days to draw them out but meeting with the alumni has reignited my commitment. They walk in the room after 20 years and I watch them drop their guard as they look around and remember who sat where. They mostly remember those knuckleheads who made them laugh. In the new photos, I try to match the background as close as possible but everything in my room has changed. Walls have been moved. Venetian blinds gone. By matching the compositions as best I can, I hope the new surfaces silently act as the shifting sands of time.

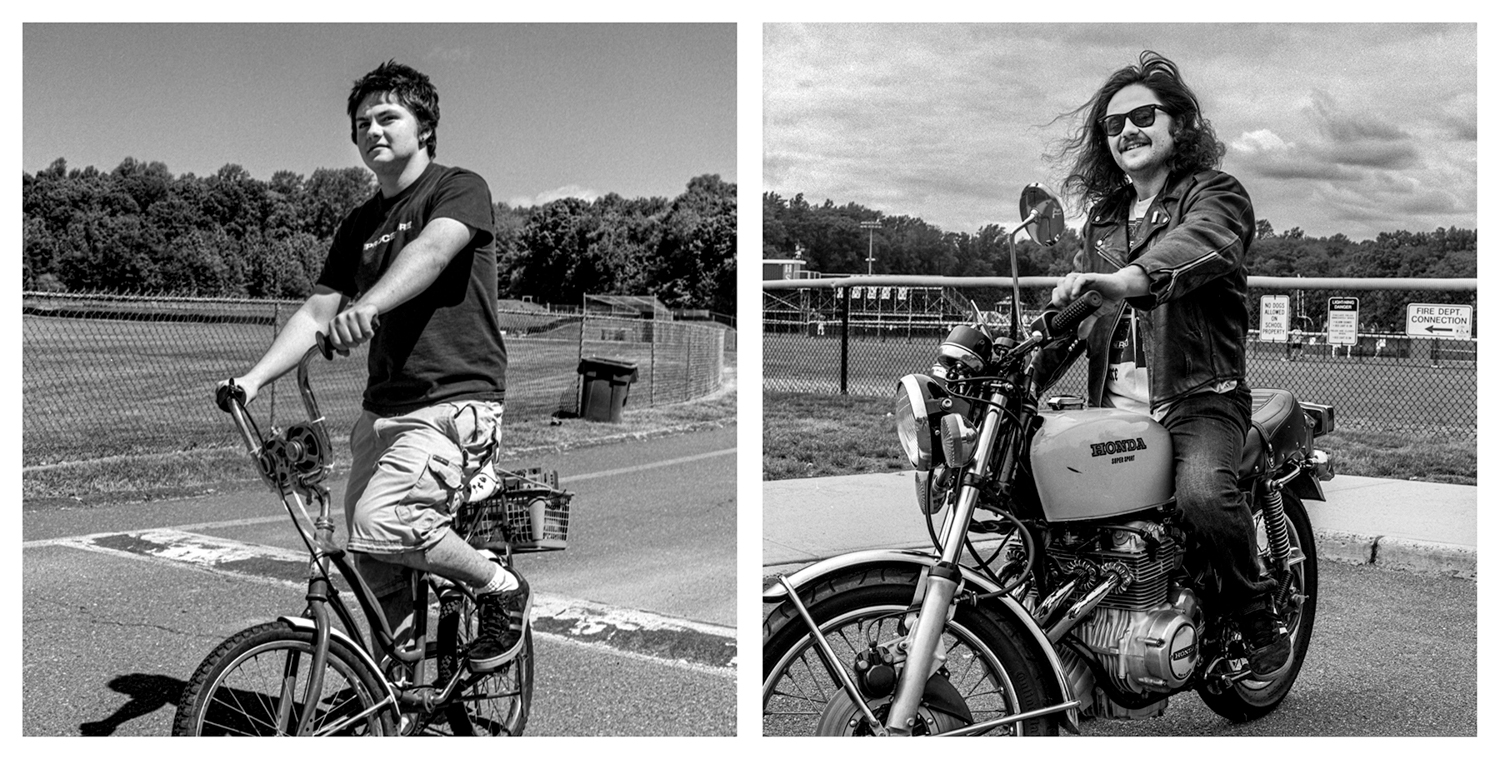

DG: This project has that attractive “then and now” motif, as it’s fun to identify visual similarities and differences between portraits. I find it interesting to consider the gap in-between, and the changes that inevitably occurred in the time from one image to the next. I’m curious about your view on this—particularly in how you approached photographing these people. Would you describe your evolution as a photographer from one frame to the next?

CB: I’ve always been fascinated by that mental process that happens when you run into someone you haven’t seen in a long time. There is that initial shock over their growth or aging or surprising new sense of fashion. Then I feel it, that thing about them that hasn’t changed at all. It’s wonderful to see these students again, but that act of recognizing something unchanging is what I was initially after in the photos. Originally, I thought I would just photograph the kids who spent the most time in the program or the kids in the strongest “then” photos. But that’s not the way it has gone so far.

I think I ran into the first one when I was taking students on the train to NYC. Though I physically recognized him immediately, I was having a hard time believing it was the same person. He had definitely been through some things. It’s weird how surprisingly impressive maturity can be. Perhaps I’ve learned to never expect it after 25 years of teaching a high school elective. He stayed with us for awhile and eventually agreed to come to school and have me reshoot his photo. That session gave me the courage to call up a few Mom’s whose numbers I had. Their kids called me back that night. Otherwise, word of mouth is mostly how it is happening. I hear from one subject that so and so wants in. I get their info.

It is still terrifying for me to reach out. They don’t all reply. Some say yes, then cancel, reschedule, then cancel again. I convince myself that they hate me and then they finally show up and give me the biggest smiles I’ve ever seen.

As a photographer, I’ve unfortunately devolved into someone whose eyesight no longer allows her to use that waist level viewfinder. Luckily, I have since found many other pathways to that transcendent state of mind. I don’t know if that would have happened if I had not made those first ten or so “now” portraits right before the lockdown. They opened the door again. Without those, remote teaching might have broken me, but instead it just gave me plenty of time to remember who made those pictures in the first place.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

L. Kasimu Harris: New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging at MOMAMarch 10th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026