Lingxue (Luna) Hao: Moon Phase: The Moments Between Wax and Wane

For the past few days, we have been looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Lingxue (Luna) Hao and I discuss Moon Phase: The Moments Between Wax and Wane.

Lingxue (Luna) Hao is a photographer from China who is now based in LA. After graduating from Beijing Film Academy, she worked as a food photographer for two years. While studying photography at the Savannah College of Design and Art, she turned her focus to telling stories through the camera. She is particularly interested in finding beauty from the ordinary and mundane and creating a virtual diary based on everyday love, loss, and reflection.

Follow Lingxue Hao on Instagram: @luna___hao

Moon Phase: The Moments Between Wax and Wane

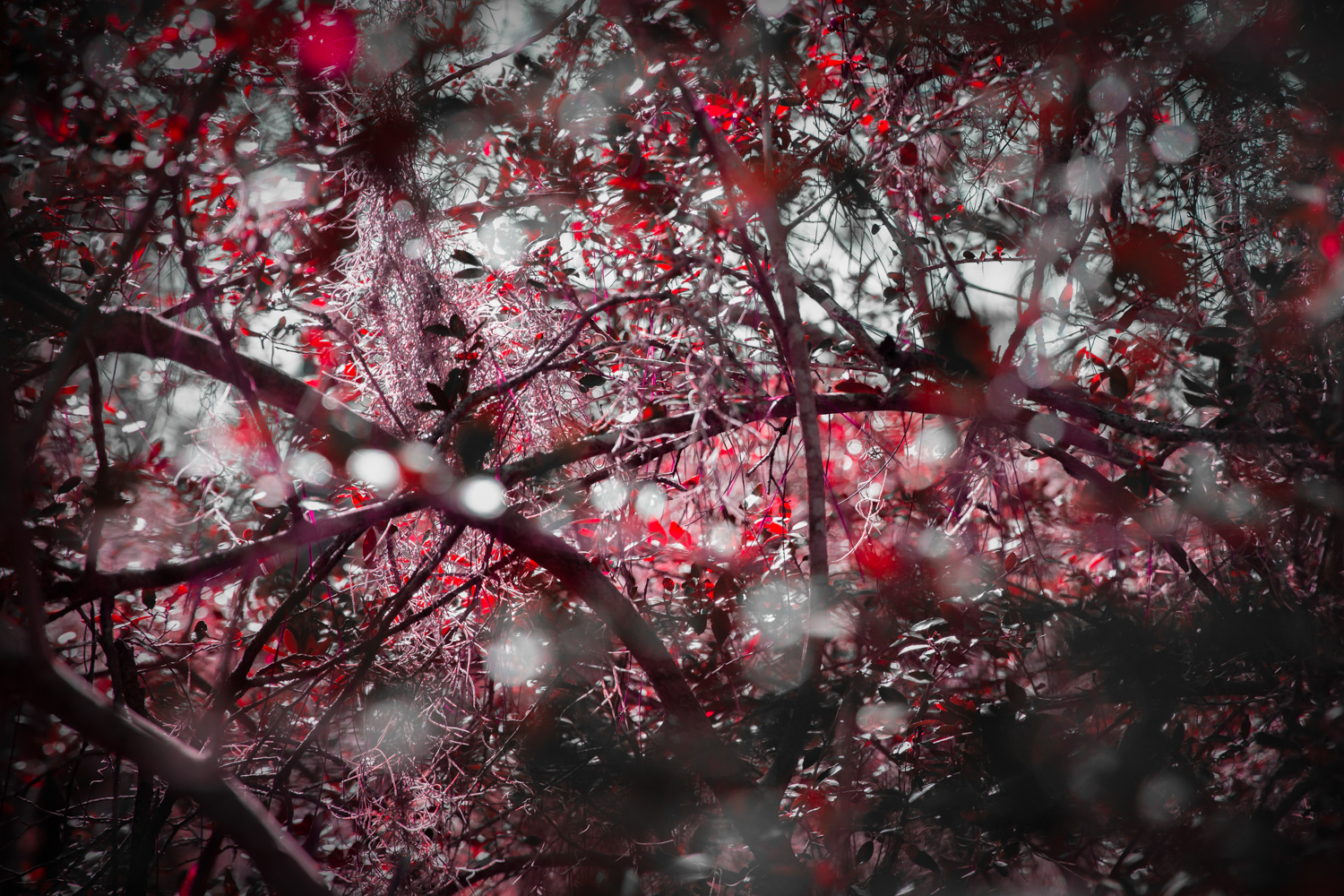

Moon Phase: The Moments Between Wax and Wane is an interpretation of depression through the art of photography. My photographs explore my own experiences with this invisible disease. They represent the torment and pain that I navigate with major depression. They also record my constant struggle with mental health. This body of work acts as a visual diary about a depressive patient that I created as a photographer. The process of photographing and editing this project is also the process by which I find a productive way to communicate with the outside world. The purpose of my work is to help those who may be indirectly impacted by depression to understand mental illness more comprehensively and establish an accurate portrayal of this very real concern. We live in a society where people still hold prejudices against those with mental health issues and misunderstand them. My photos serve as an invitation to viewers to raise awareness and support for the people around them who struggle with this widespread issue.

Daniel George: Tell us about the beginnings of this project. When did you decide to begin this exploration of your mental health?

Lingxue Hao: The project officially commenced in the autumn of 2018, but its inception traces back to the spring of 2017. In the spring of 2017, I was diagnosed with severe depression and moderate anxiety in China. At that time, due to the severity of my condition, the doctor recommended hospitalization for a more effective and rapid recovery. However, my father adamantly refused, believing that even an ‘open ward’ was no different from sending his daughter to a mental institution. In his perception, I was merely caught in ‘prolonged emotional distress,’ and he thought I should make myself busier to dispel these negative emotions.

My mother, with over 20 years of experience in the healthcare profession, also struggled to accept this reality. She sought assistance through a series of religious methods, arranging for individuals with connections to perform exorcism rituals at home, aiming to rid me of ‘negative attachments.’ In a mentally unstable state, laden with a plethora of medications, I embarked on my journey to study abroad in the United States. While coping with the challenges of demanding academics and cultural adjustments, I casually addressed my treatment.

In such circumstances, recovery seemed unlikely, and I encountered increasing difficulties in both academic pursuits and interpersonal relationships. The cumulative stress and anxiety prompted a desperate need to find an appropriate outlet and means of expression. As someone not adept at verbal communication, I chose my most familiar and trusted tool—the camera. I began attempting to use visual language to articulate what my mind and inner self were undergoing. As the collection of these photos grew, encouraged by my professors, I formally incorporated this photographic endeavor and these images into my MFA project, initiating the documentation of the entire process of grappling with depression.

DG: I am interested in your creation of “a depressive patient” as a means of narrating your personal experiences. Why did you feel it was important to portray this as if through the experiences of another?

LH: Firstly, I think we can agree on one thing—visualizing an invisible illness like depression poses the greatest challenge. Initially, my vision for this project was quite different from what it has become. I had envisioned creating something like a ‘Depression Handbook.’ The idea was to document and visually express every manifestation and symptom, enabling individuals facing similar struggles, like me, to use it as a tool for a straightforward explanation to their friends and family, fostering care and understanding.

However, during the actual process of shooting, I quickly realized the impracticality of these goals. Even in today’s society, where reading images is quicker, more convenient, and more straightforward than reading text, the vast realm of contemporary photography is already filled with countless predecessors and peers undertaking projects with similar intentions. However, expecting that a few images could make others truly empathize with the invisible pain and struggles is an unrealistic notion. Susan Sontag, in ‘Regarding the Pain of Others,’ mentions a theory that when too many images expressing pain bombard the audience in a short period, they become numb and unconsciously want to escape, turning one’s work into mere answers for comprehension is a dull and superficial choice.

In light of this, I felt that if I wanted to tackle this, I should reverse my approach. Starting from my own experiences, I discarded the additional expectations and constraints attached to the project, maintaining a gentle and honest attitude. Remaining truthful and open to all viewers, I aimed to showcase as many details as possible, allowing viewers to immerse themselves for a more immersive and profound understanding.

DG: I was drawn to the journal-like manner of storytelling that your images (individually and collectively) possess. Would you describe your use of that particular visual language and the importance of dividing the work into chapters?

LH: I broadly categorize my captured content into three types. The first category is undoubtedly self-portraits, as it involves my own story, and I have to be in front of the camera. However, I have a strong aversion to self-portraits and being in front of the camera, which is why the second part comes in—lots of landscapes and small objects from my daily life. I feel these things I see and choose to have in my life somehow represent my identity. For example, in the first chapter, there’s a photo of black water with green grass growing in it, and I named it ‘Self-Portrait’ because I believe that image, both in content and atmosphere, more accurately portrays my struggle at that time than a photo of my face would. I think including more everyday objects and scenes from my apartment can bring the audience closer, creating an honest and intimate atmosphere. The third part more directly displays the symptoms of depression—traces of self-harm, lethargy, insomnia, and so on. However, I intentionally controlled and softened the portrayal of this part because I didn’t want to ‘scare away the audience.’

As for why I divided them into three chapters, during the process of shooting and reviewing a considerable number of images, I noticed distinct phases and realized they perfectly corresponded to changes in my physical and mental states. Hence, I decided to edit them separately. The purpose was to create an atmosphere reminiscent of reading a personal diary while providing a clear timeline. The first chapter depicts my most primitive state, corresponding to a period of complete despair and darkness when I hadn’t yet sought conventional medical help. The second chapter is from late 2019 when I began receiving regular medical assistance with the support of friends, documenting my fluctuating mental state. The third chapter delves into the process of learning to coexist with depression after achieving stability, finding a balance between the illness and life.

DG: You mention that your intention is to “establish an accurate portrayal” of those who experience depression—to create greater understanding for those indirectly impacted. How do you feel your photographs accomplish this?

LH: When viewing a photograph, three factors come into play: the subject, the camera, and the photographer. Typically, the viewer sees the photo from the perspective of the photographer. However, in the ‘Moon Phase’ project, I assume two roles—I am both the photographer and the subject. This merging of roles means that the photographer and the subject become one in this project, resulting in a more open and transparent presentation for the viewer.

Beyond the three main chapters I mentioned earlier, the ‘Moon Phase’ project also includes two smaller branches: the ‘Sleeping Study,’ captured using a pinhole camera to depict long-term insomnia symptoms, and the ‘Run Away Series,’ showcasing the instability of mental states and the loss of security during driving. Unlike the visual diary presented in the three main chapters, these two smaller branches aim to objectively and directly showcase the symptoms of depression.

Overall, throughout the entire creative process, I haven’t strongly emphasized the cause-and-effect narrative or outcomes. Instead, I’ve crafted a gentle overarching relationship. I appreciate the interactive aspect of storytelling, where, after laying down the main storyline, the audience is invited to fill in the details through their own reading and imagination.

DG: In your statement, you write that this project represents a “productive way to communicate with the outside world” about depression and mental health. Could you talk more about the value of being vocal about these experiences? What does it offer (you, or others)?

LH: I’ve been grappling with depression for over six years, and the process of shooting and editing this project has taken more than three years. Personally, when I started this project, I didn’t have high expectations for the positive impact it might have on me. However, throughout the entire creative process, I discovered that by documenting and organizing my experiences through images, I gained an opportunity to objectively examine my chaotic life. Depression itself is a process of self-destruction, and I wasn’t aware of how deep into the abyss I had gone. These photos turned my subjective pain and fantasies into something objective, providing me with a space for self-reflection.

For others and the external world, I believe my project brings more in terms of support and discussion. I aim to demonstrate through practical action the feasibility of using photography as an artistic form to narrate personal mental health matters. Simultaneously, I want viewers undergoing similar ordeals to feel that they are not alone. For those who simply view and read this project, my hope is to establish a platform for communication and discussion based on this project. By sincerely showcasing my personal experiences and life details, I aim to spark discussions related to depression and mental health issues.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Gadisse Lee: Self-PortraitsDecember 16th, 2025

-

Scott Offen: GraceDecember 12th, 2025

-

Izabella Demavlys: Without A Face | Richards Family PrizeDecember 11th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 2November 27th, 2025

.jpg)