Hannah Schneider: Vanishing World

For the next few days, we are looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Hannah Schneider and I discuss Vanishing World.

Hannah Schneider is from Raleigh, North Carolina. She is a Duke MFA Experimental and Documentary Arts candidate. Since discovering the darkroom in 2021 as an undergrad at Meredith College, Schneider has fallen in love with the experimentality of creating work there. Her work merges archival and digital photographic practices, transcending the line between photography and digital art. Schneider has had work published in The Colton Review (2020, 2021, 2022, 2023) and presented in the Annual Juried Student Art Exhibition (2021, 2022) and DISRUPT Exhibition (2023), and was a finalist for Photolucida’s 2023 Critical Mass. She is passionate about using photography to push the boundaries of the media and create narratives that make visible what cannot be seen. With her work, Schneider hopes to create captivating, personal pieces that leave the viewer in contemplation.

Vanishing World

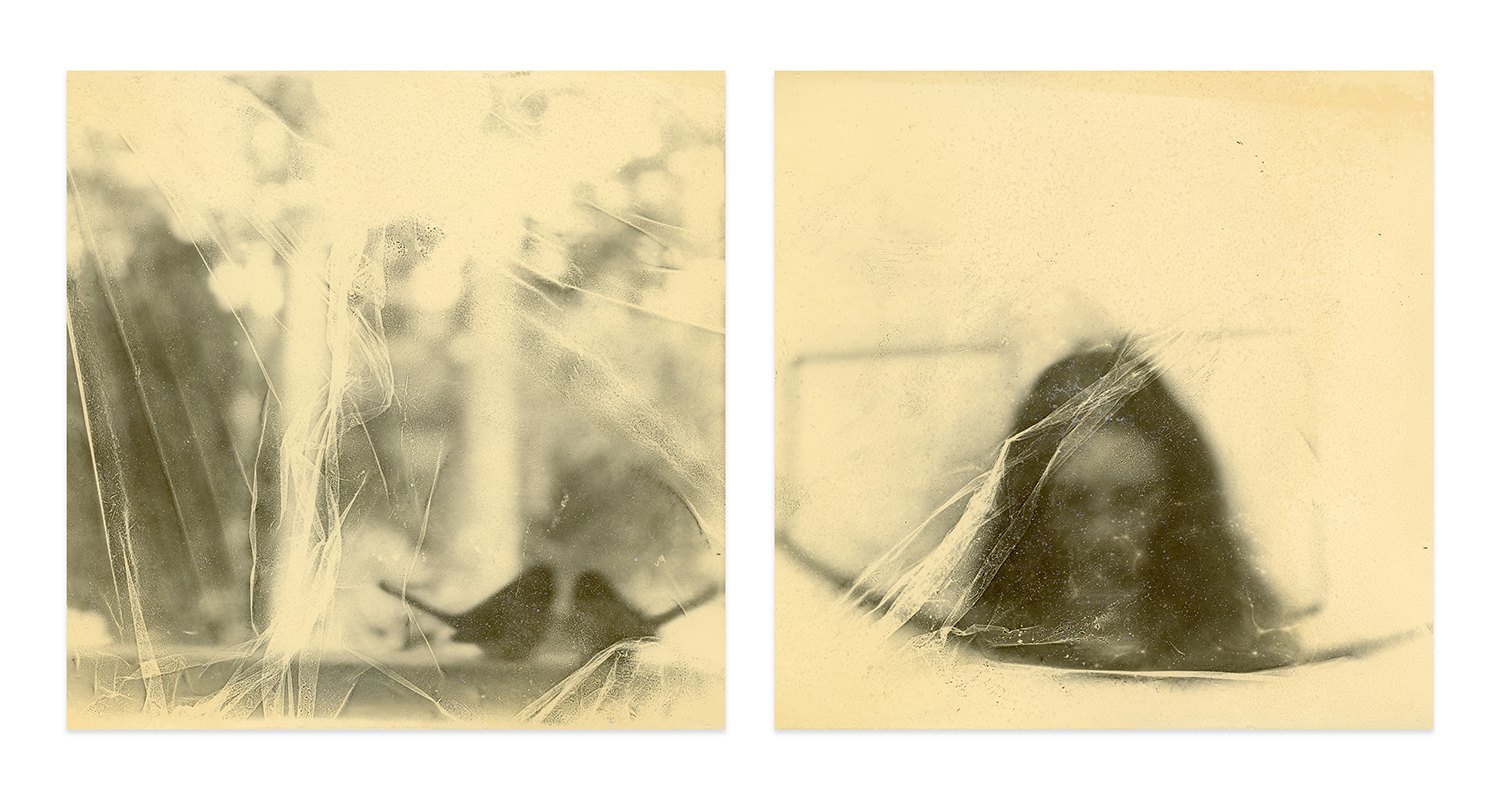

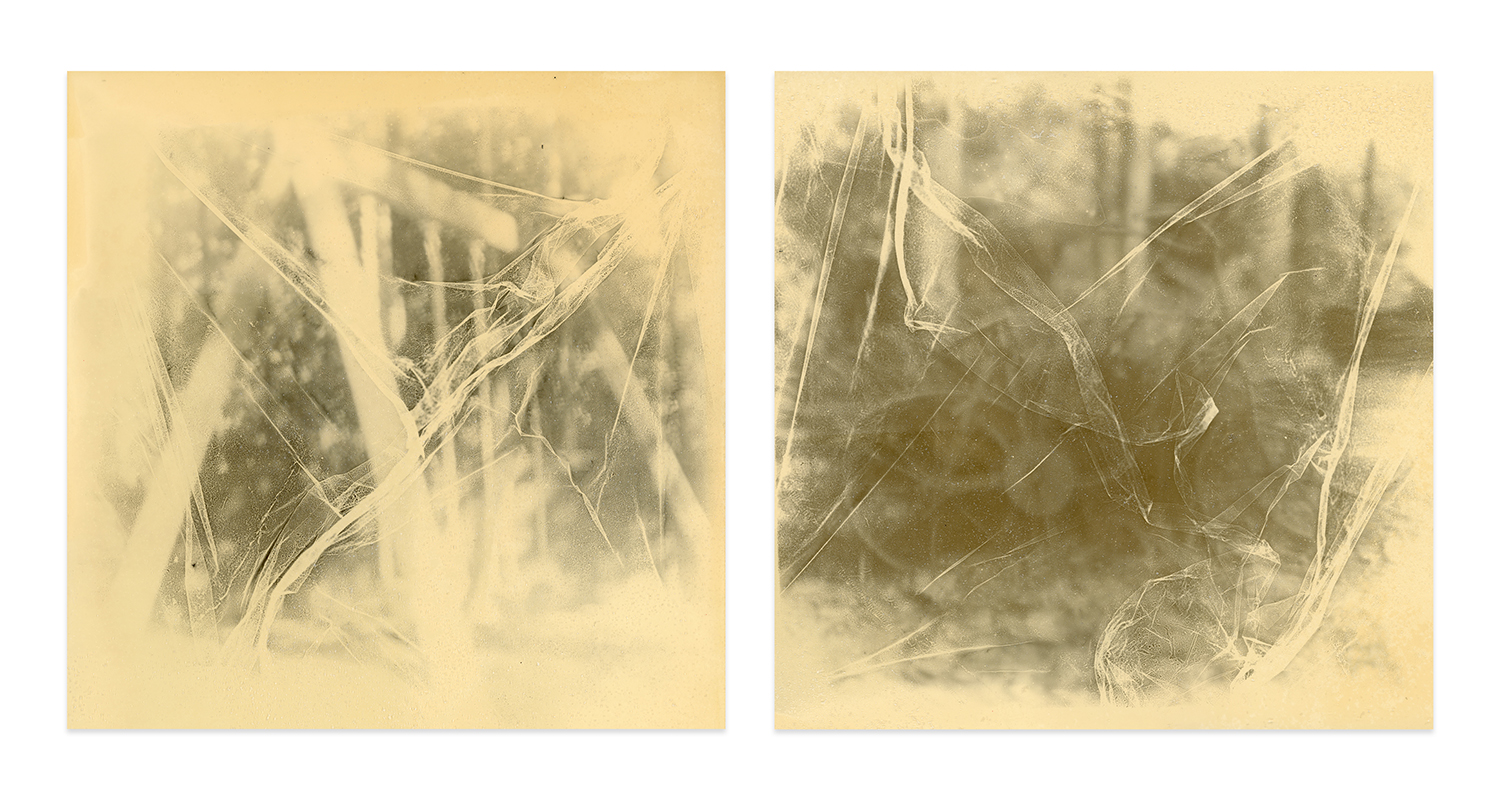

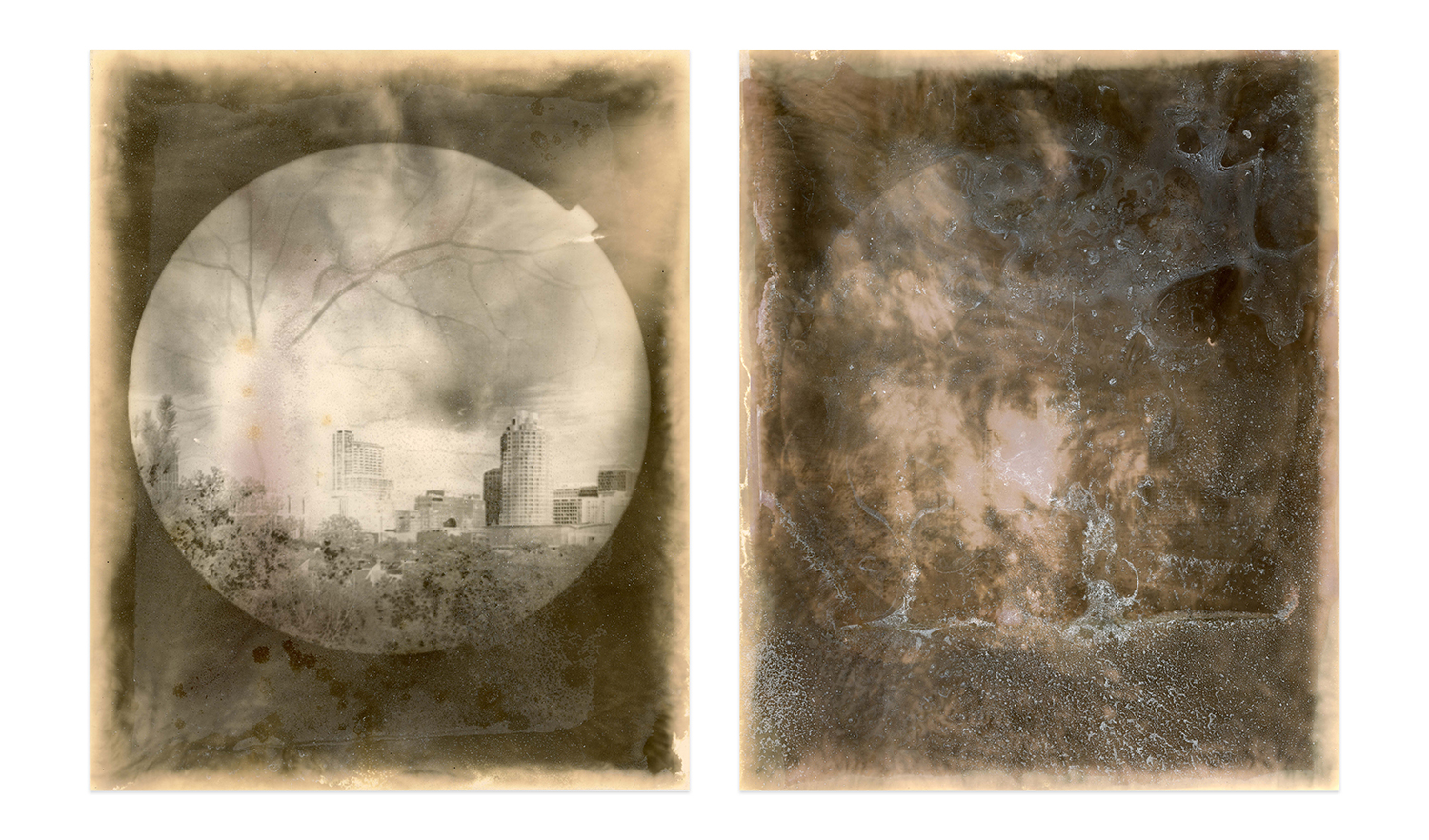

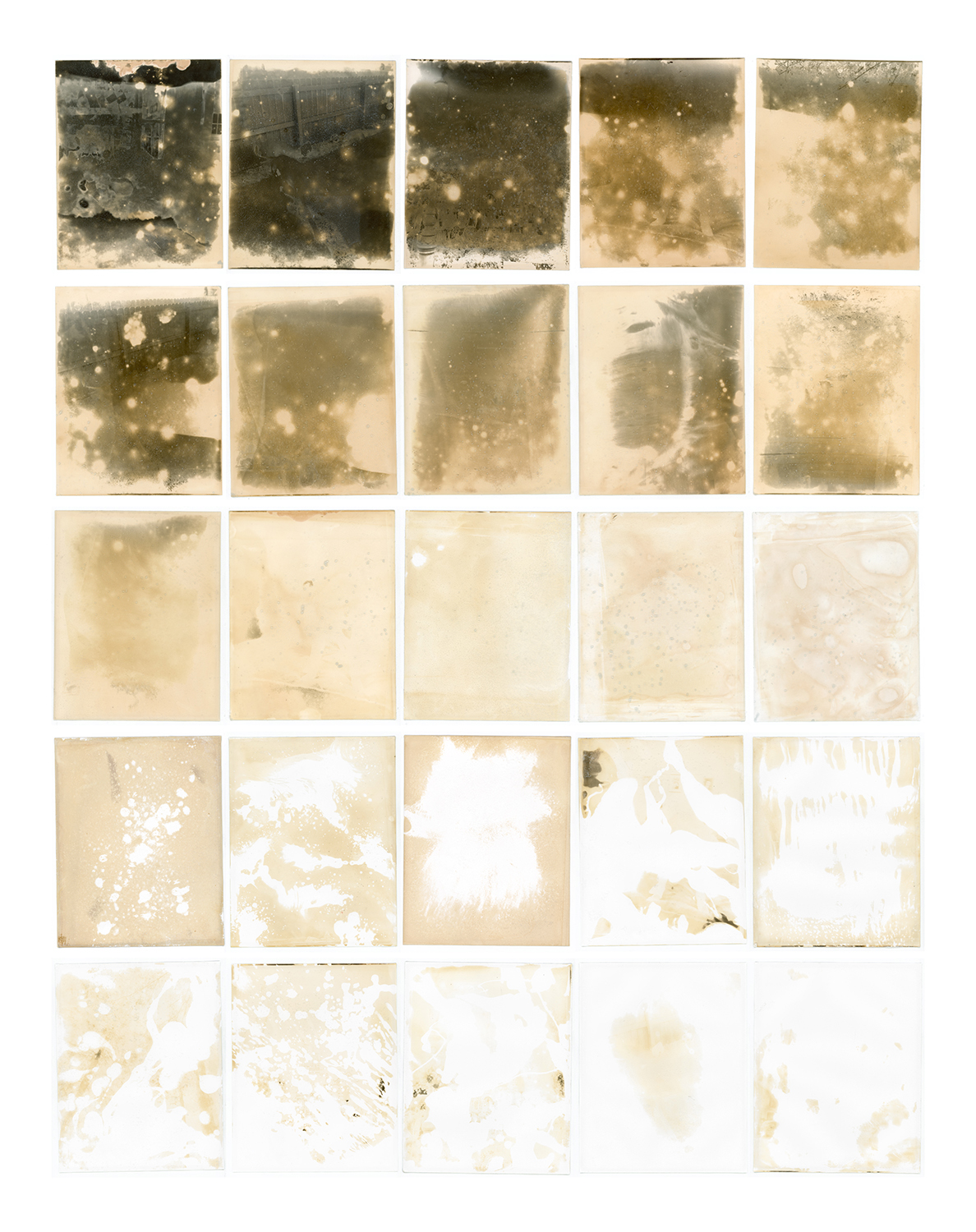

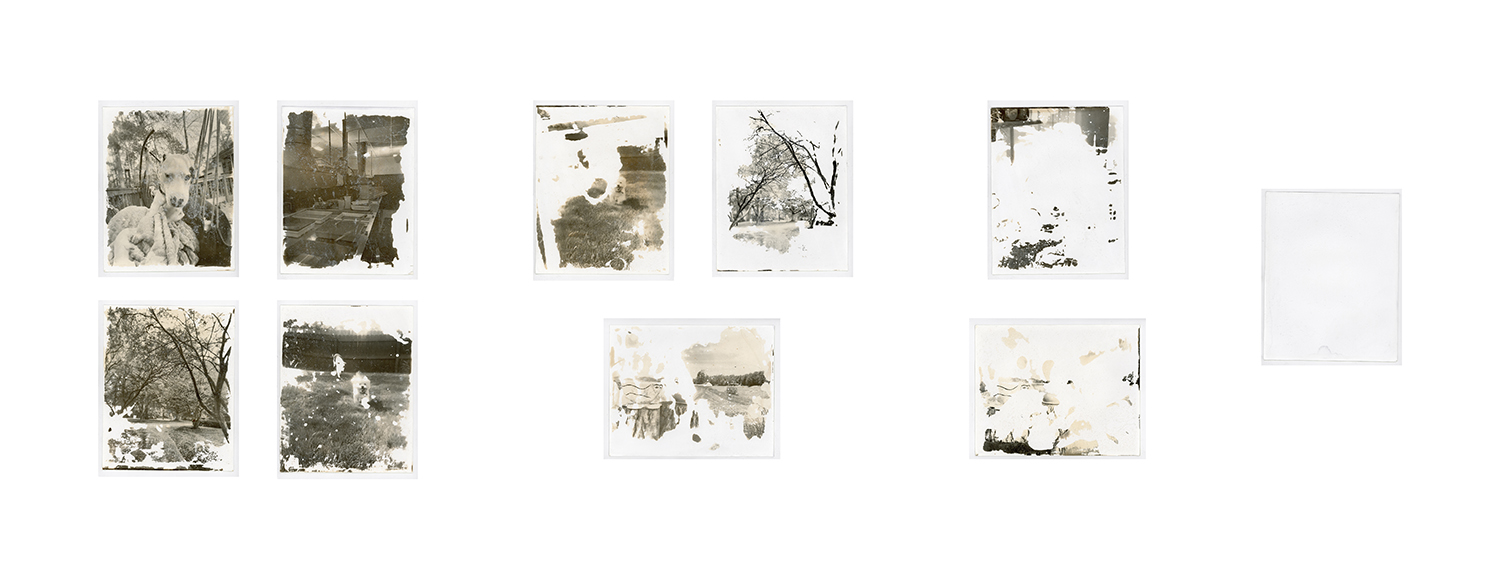

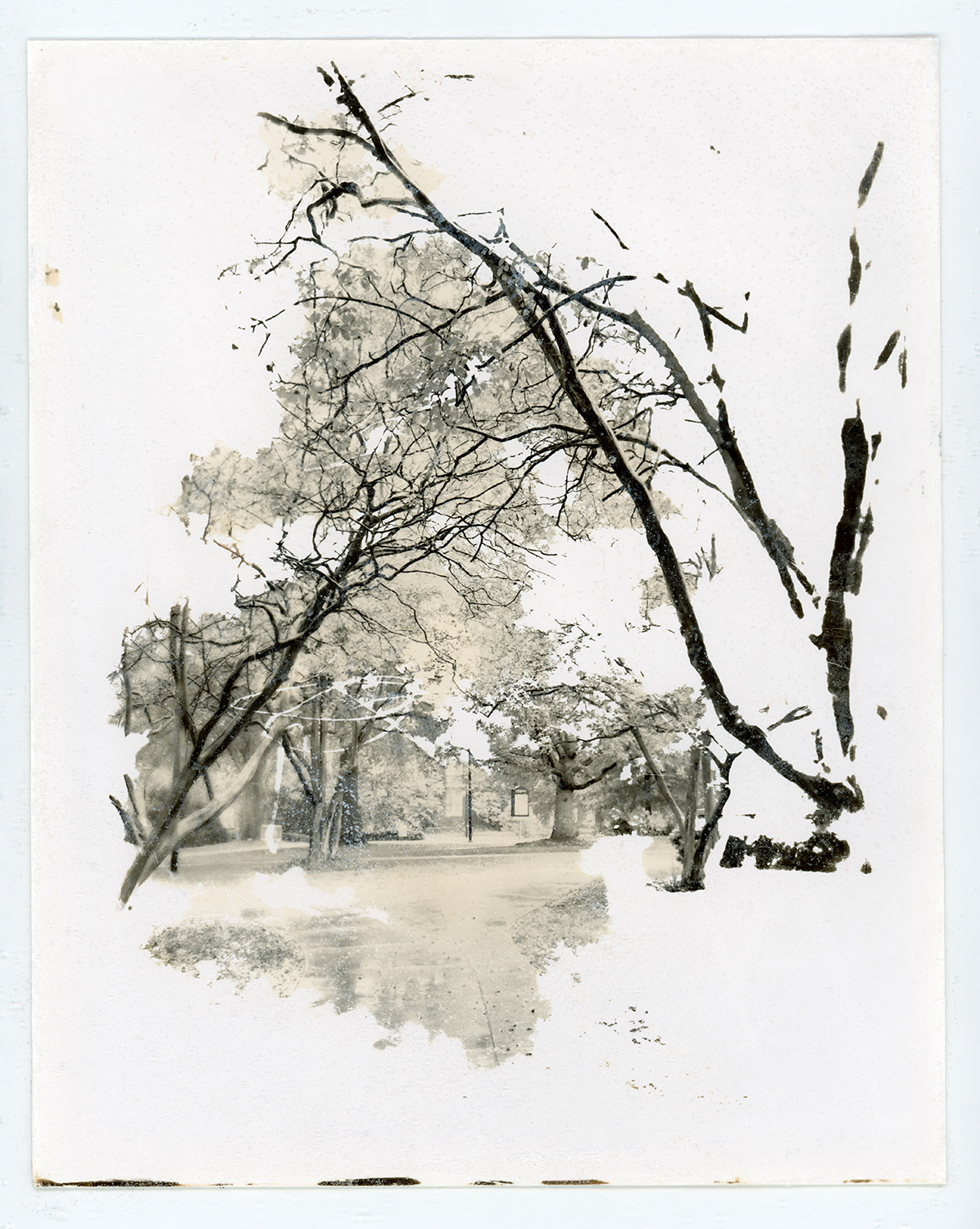

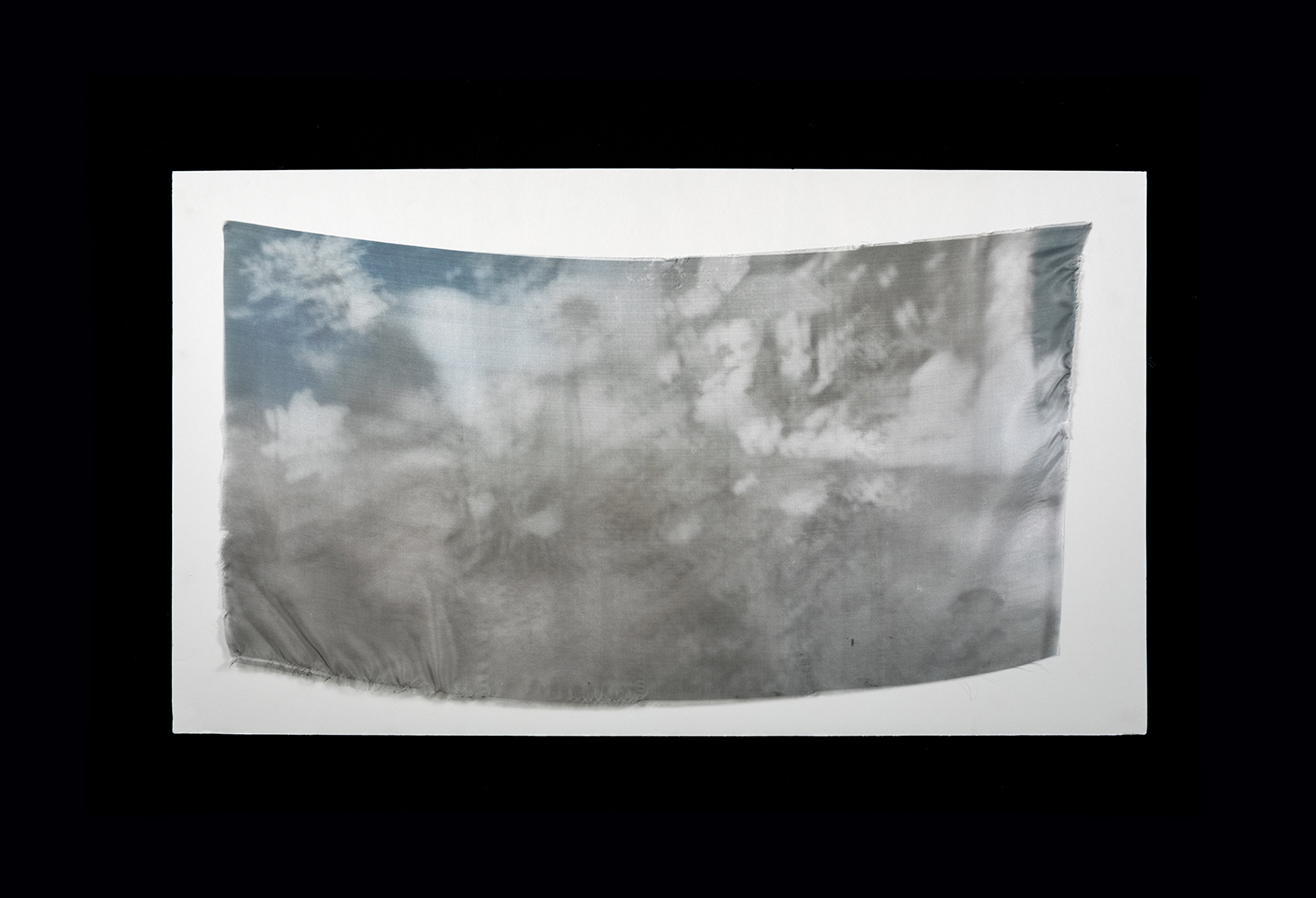

As an individual diagnosed with the genetic disorder Bardet-Biedl Syndrome, I have struggled with the increasing possibility of going blind. As an artist, losing my vision would be particularly tragic since I use my sight as an essential tool for creating photography and visual art. Through this series, the camera is used to visualize a world where I may no longer be able to see. The darkroom was intentionally used as an aspect of creating this series, as it deprives the artist of sight and clarity as the work is created. Images were purposefully deconstructed with techniques that are difficult to control, including burning, bleaching, dissolving, and the inconsistent but nontoxic Caffenol developer. The pieces were then fixed with salt, leaving a crystalized residue and resulting in an image still sensitive to light. After viewing the series, I would like the viewer to be left struggling to hang onto something tangible while the images appear to dissolve in their sight. In addition, I hope that they have more empathy toward those struggling with a rare disease. It is estimated that 1 in 10 individuals in the United States and 300 million individuals worldwide are living with a rare disease.

Daniel George: Tell us how this project began. When did you determine to confront your diagnosis with Bardet-Biedl Syndrome through your creative practice?

Hannah Schneider: When I was first diagnosed in December of 2021, I was overwhelmed with fear and anxiety and felt alone. Bardet Biedl Syndrome affects various parts of your body, not just your eyes, but my sight was and is my concern, as it is the primary sense I rely on to create art, work on design projects, and take photographs. I have a degree in graphic design, so what will happen if I lose my vision? What will I have to fall back on? Without my ability to create, I am terrified that I will feel lost and purposeless. I looked online and had trouble finding any artists or designers in a similar situation, making me realize that when others are confronted by life-changing medical diagnoses, they tend to keep it to themselves instead of talking about it. Creating photographic pieces about my diagnosis gave me the opportunity to utilize my creative outlet and share my story while spreading awareness about this rare genetic condition that very few individuals know about. I hope that there’s someone out there who, when they find my work, feels understood and less alone.

DG: Regarding your process, would you share more about the variety of approaches to making these images—from darkroom manipulated prints to retinal scans? What do each of these techniques offer the body of work?

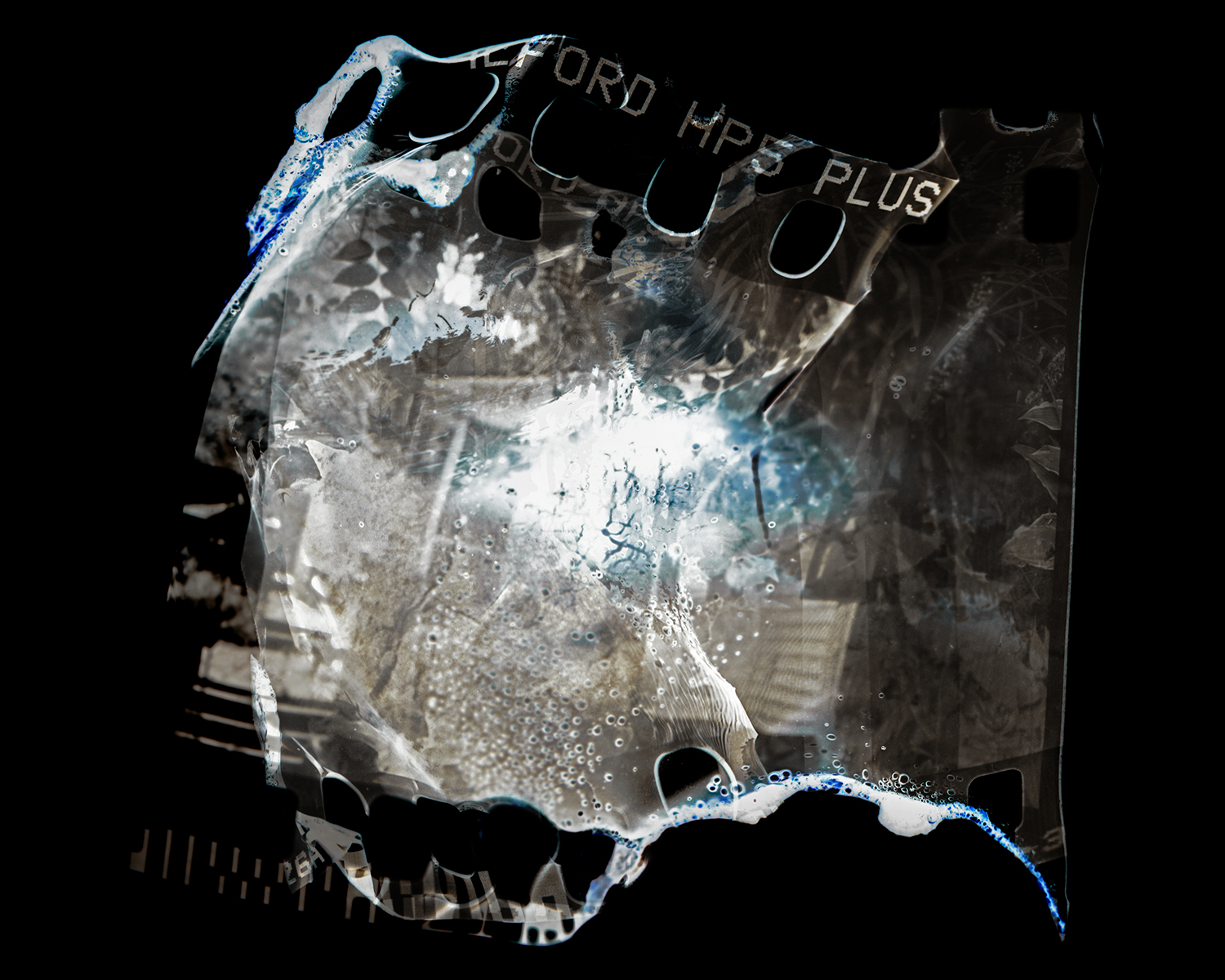

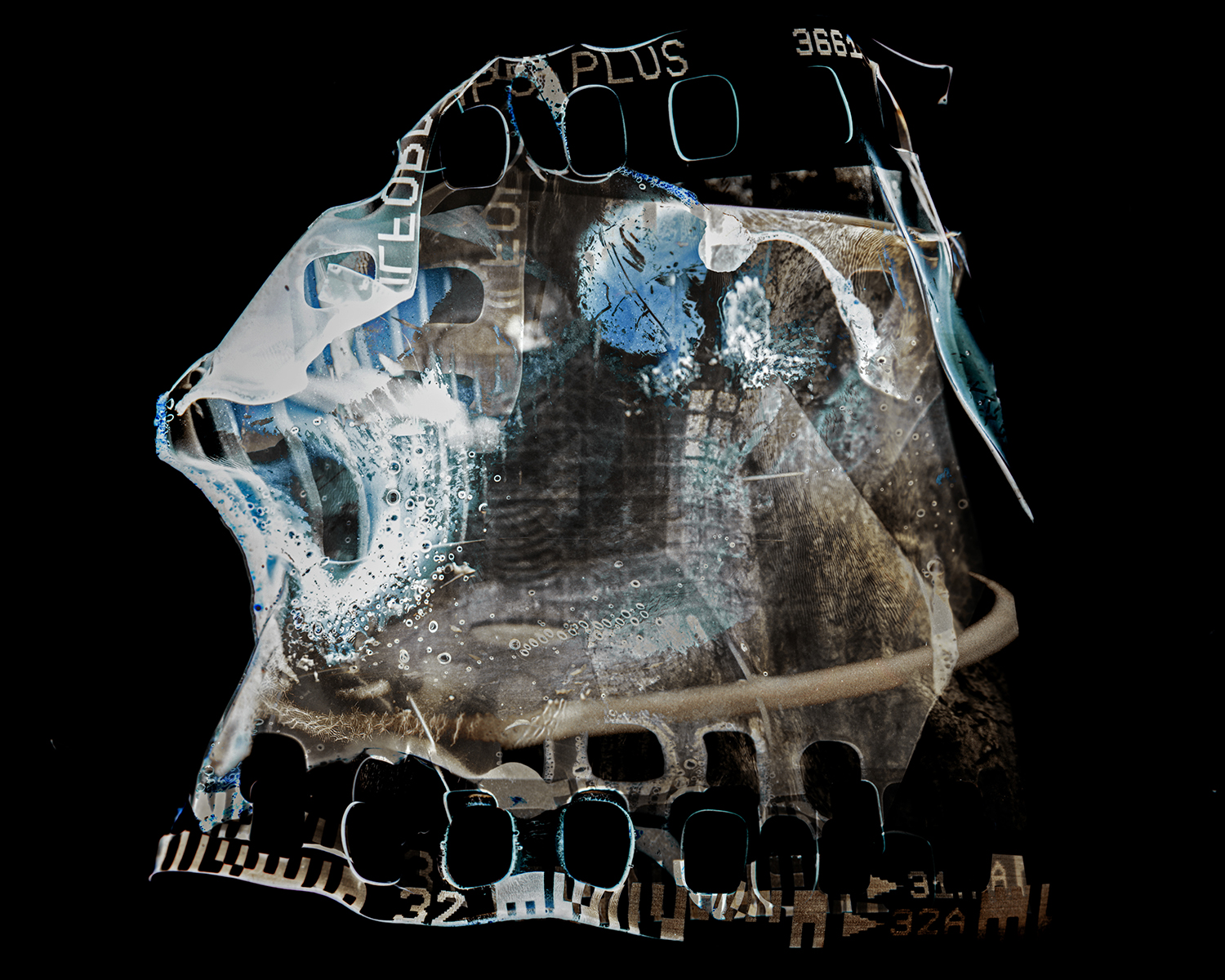

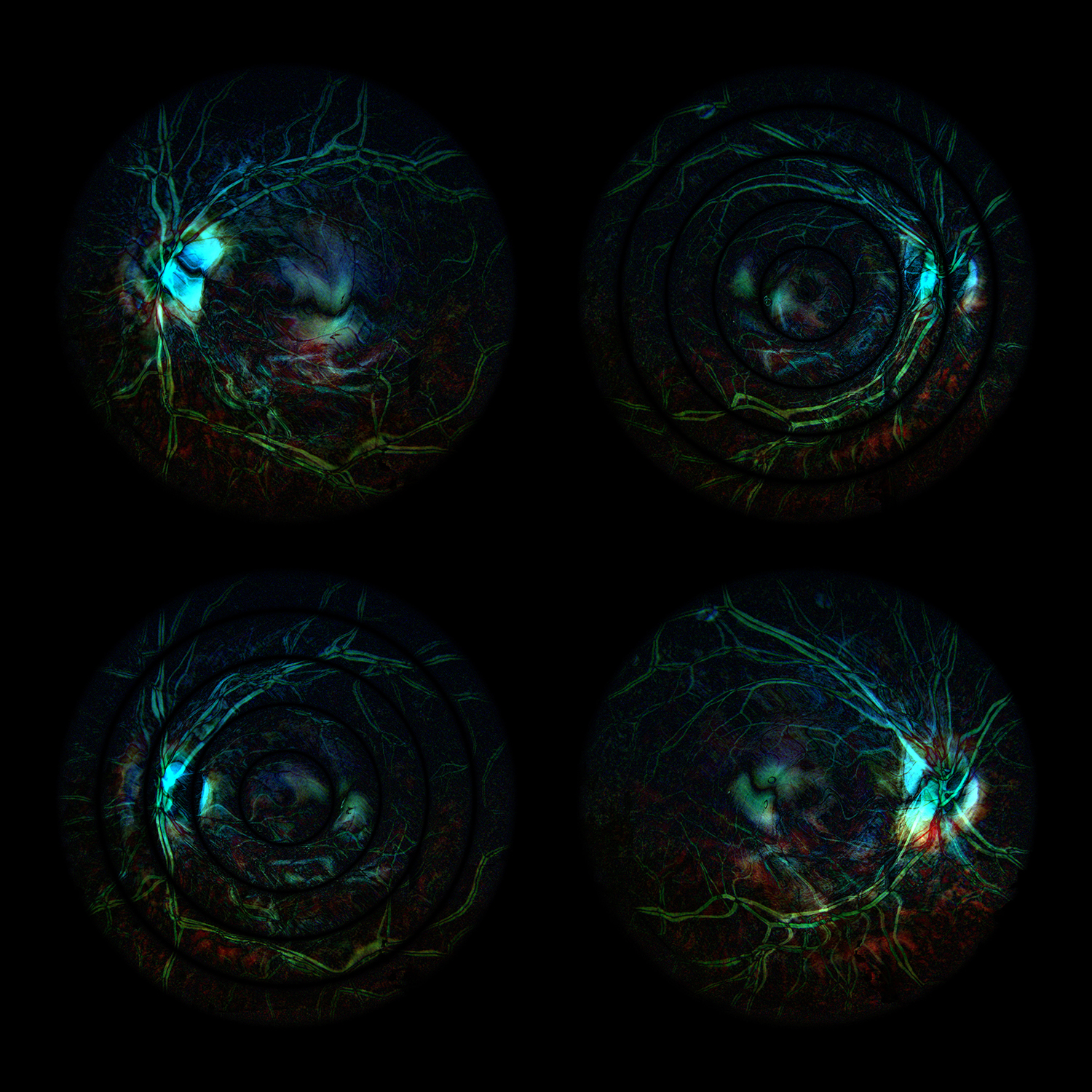

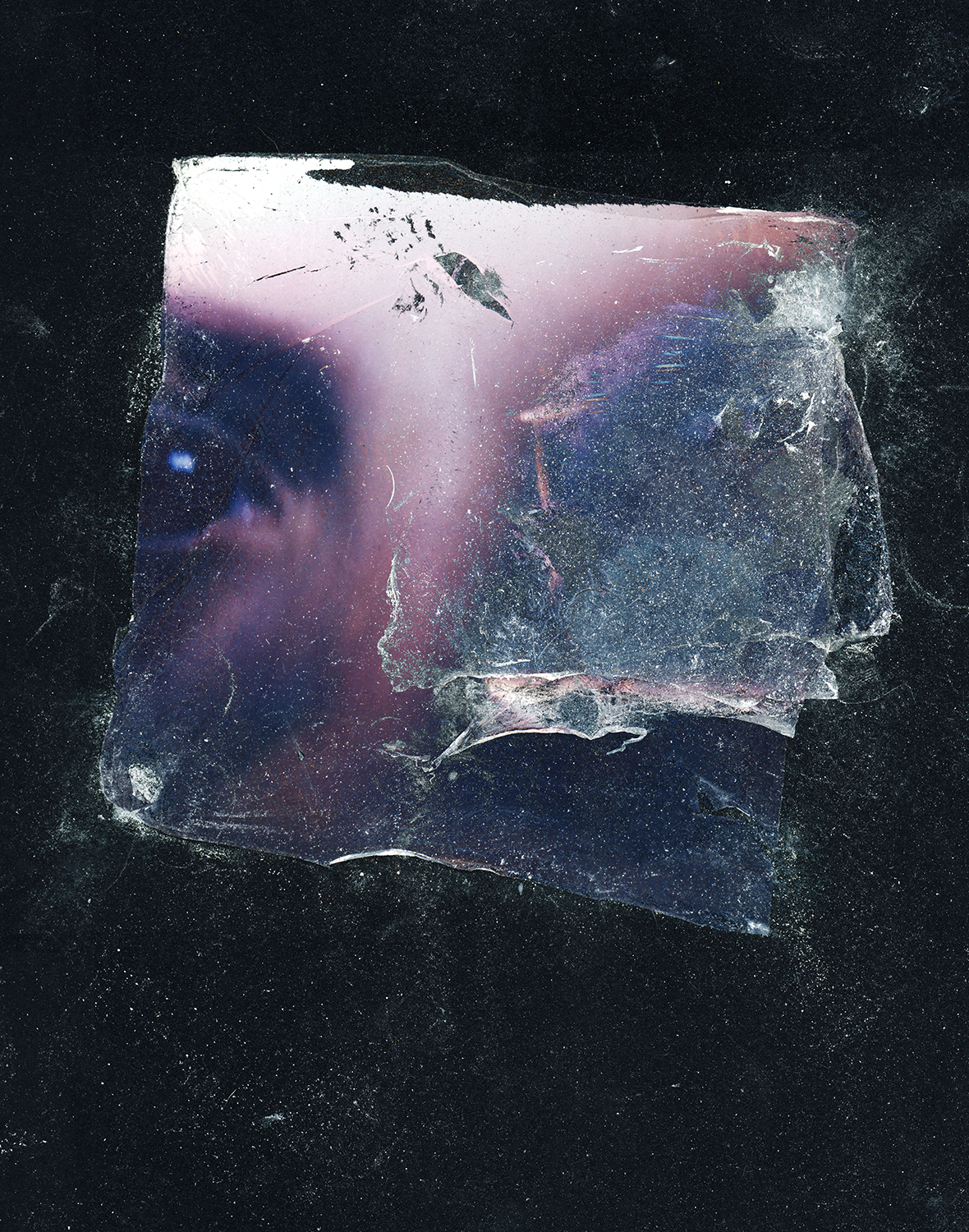

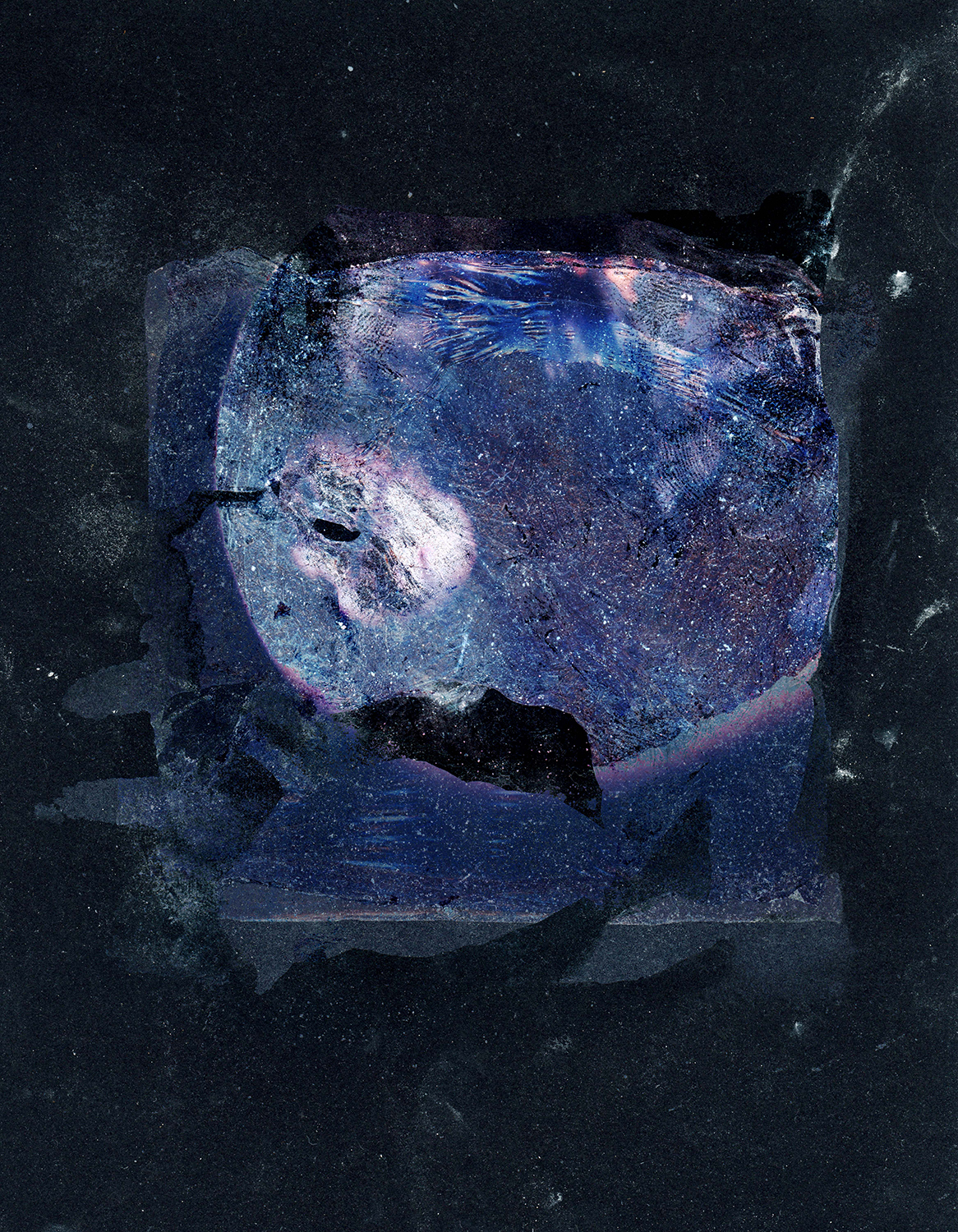

HS: The pieces in this project are made using various processes. By utilizing the darkroom, a space where I work primarily in the dark, I am forced to create prints without my full vision. I don’t know what the future of my sight is, but I know that I don’t want to give up creating, and I know that there are blind artists and photographers out there. Working in a darkroom mirrors what I may have to experience in the future, creating without my sense of sight. With my work, I enjoy exploring different experimental processes, and in this project, I purposefully utilized different deconstructive processes that would communicate themes of decay, impermanence, and loss. These processes included bleaching, burning, inconsistent exposure, solarization, creating chemigrams and polaroid lifts, and placing saran wrap over negatives printed onto transparency film. I worked with imagery that was important to me (my pets, family, home, workspace, trips I’ve taken, etc.), representing my fear of eventually being unable to see who and what I care about most. In addition, I worked with color fundus photographs taken of my eyes, allowing me to directly incorporate the health of my retinas and the current state of my vision into the project.

DG: Something that we cannot experience when viewing your work online is how the images change due to their continued sensitivity to light (after having been fixed with salt). I feel that this attribute effectively invites viewers to face what you describe as a struggle to “hang onto something tangible.” Would you elaborate on your choice to create this sort of impermanent photograph?

HS: With this project, the first instance I realized how impermanent photographs can be was entirely accidental. I left developed but unfixed contact prints in a paper safe and bleach that was not completely rinsed off leaked through the stack, removing parts of the images but leaving me with beautiful remnants that spoke about uncontrollable loss. Thrilled with this unexpected development, I decided to work with different processes that would allow me to continue to explore these themes of decay and deterioration. Much of this project involved trial and error and working with the parameters I had with utilizing a darkroom where traditional darkroom chemistry was not permitted. Instead, Caffenol, a developer made using vitamin C powder, washing soda, caffeic acid, sodium carbonate, and water, and fixer made from salt and water were used. The salt fixer was not always successful, sometimes leaving unfixed areas in the image that would darken without refixing. This limitation turned into an important part of my project when I realized that the impermanence of the imagery aligned with the impermanence of my vision. The imagery will always be powerful regardless of how it changes over time, and it may even become more meaningful as it ages.

DG: I am interested in how this work addresses the idea of vision—not only literal, but figurative as well. A sort of interpretive way of seeing. As you look at these images that “visualize a world where [you] may no longer be able to see,” what do they allow you to perceive?

HS: Although creating this project has been therapeutic and given me a purposeful direction, when I look at the work I’ve created, I perceive a profound sense of loss, making me terrified of what my future holds and how uncertain it is. Terrified that I’ll be left with nothing but darkness and mental anguish. Terrified that I will lose the ability to create, taking my greatest passion and my financial security with it. Terrified that I will no longer be able to see my loved ones, and maybe even one day forget what they looked like. No one knows what their future holds for certain, but in my case, there is a key aspect that I know is severely at risk. You don’t need your sight to live or even to have a fulfilling life, but for me, my sight is everything to me. It is essential for my creative passions and for what I had planned for my future. I hope that one day, not that far away, there will be treatment for people like me who experience retinal degeneration due to inherited genetic disorders. However, for now, I can only take it one day at a time and monitor the state of my vision and new symptoms that develop.

DG: Could you talk more about the idea of using photography, and perhaps with this project specifically, to create a sense of empathy toward those grappling with rare diseases?

HS: The use of photography allows me to document my experience with my rare genetic condition and the emotional turmoil experienced because of it. In the future, it may be used to document the progression of my impacted sight, whether that be through the eye scans that I continue to incorporate, the creation of pieces that mirror the level of sight I have, or perhaps the change in how I create art. Roughly 90% of the US population is unaffected by rare diseases, making it likely that most individuals have little knowledge of the experiences those impacted have. By documenting my experience instead of keeping it to myself, I can try to reach those who have no understanding of what it is like to live with a rare genetic disorder. In addition, I may reach someone who sees themselves in my work. I believe that one of the greatest compliments you can receive as an artist is that you made someone understand, or feel understood.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aurora Rojas Briceño: Amalia IrmaJune 6th, 2024

-

Aurora Rojas Briceño: Amalia IrmaJune 6th, 2024

-

Healing Riverbanks: Sebastián Mejía’s Walks Along the Mapocho RiverJune 5th, 2024

-

Mournful Cuts: The Political Collages of Amanda Sotelo SilvaJune 3rd, 2024

-

Kyle Agnew | Our Cheeks Blush Amidst Prairie GrassesMay 10th, 2024