Kioto Aoki: Proposed Ways of Seeing

Kioto Aoki is an artist, photographer, musician, educator, and book maker living in Chicago, IL. Kioto Aoki’s artistic practice spans many disciplines. Sometimes these all touch at a poetic point of grace and quietness in her visual work. I continue to be inspired by Kioto’s clever playfulness with the photographic medium. It seems nearly anything can be a camera for Kioto, even her body is sometimes a stand-in for an aperture or a 16mm film strip. Wondrous, extraordinary things are activated and pulled out from the common, everyday objects and environments when left circling within Kioto’s orbit.

Place, memory, and a longing to reactivate the past are at the root of Kioto’s work. Her visual results question what it means to document with a camera, leading to poetic depictions of proposed ways of seeing the self and exterior world. Margins of error are elongated and failures of the apparatus are anticipated or even exploited for Kioto. Inherently bound to light, the analog processes in Kioto’s works are permeated with fogged edges, scratches, grain, and dust. She lets the natural cause and effect of the unwieldy powers of happenstance and light take hold. Making her work all the more mysterious and wonderful to look at. Almost at the edge of nearly collapsing, the legibility of Kioto’s work can sometimes barely hang on.

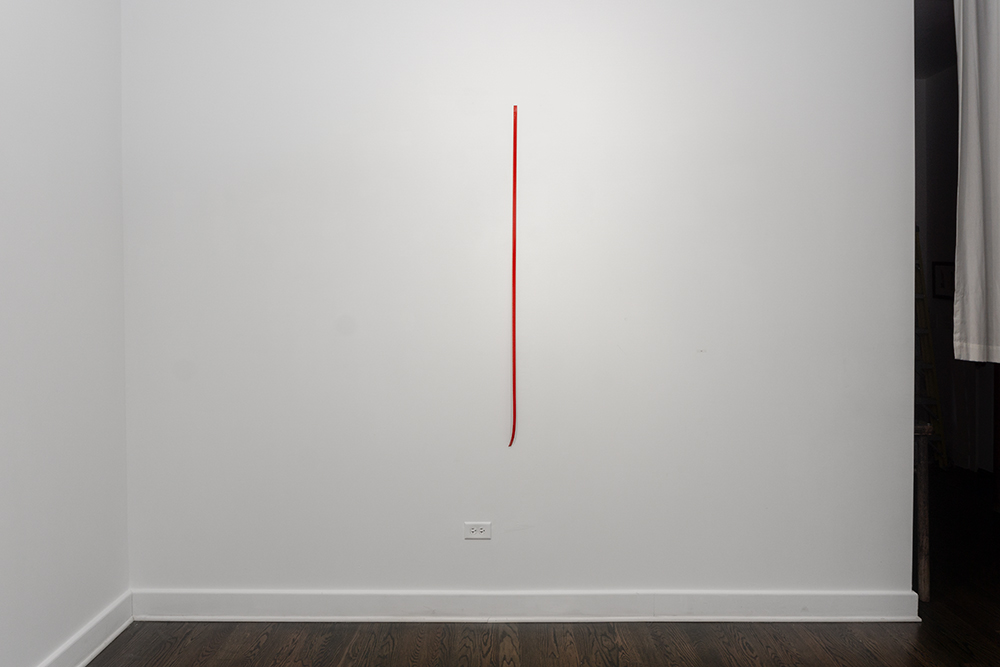

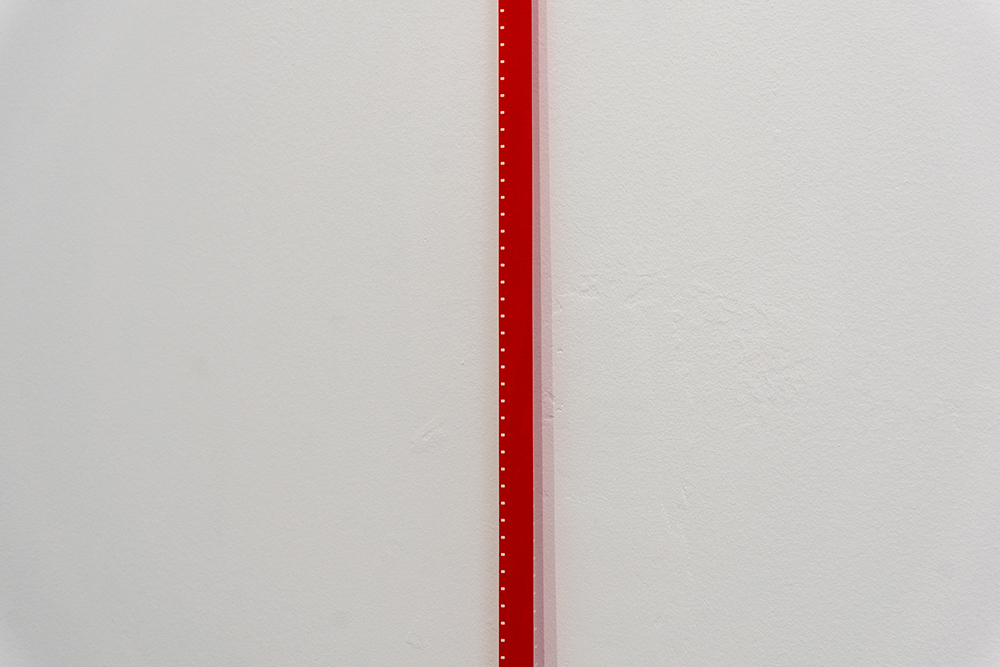

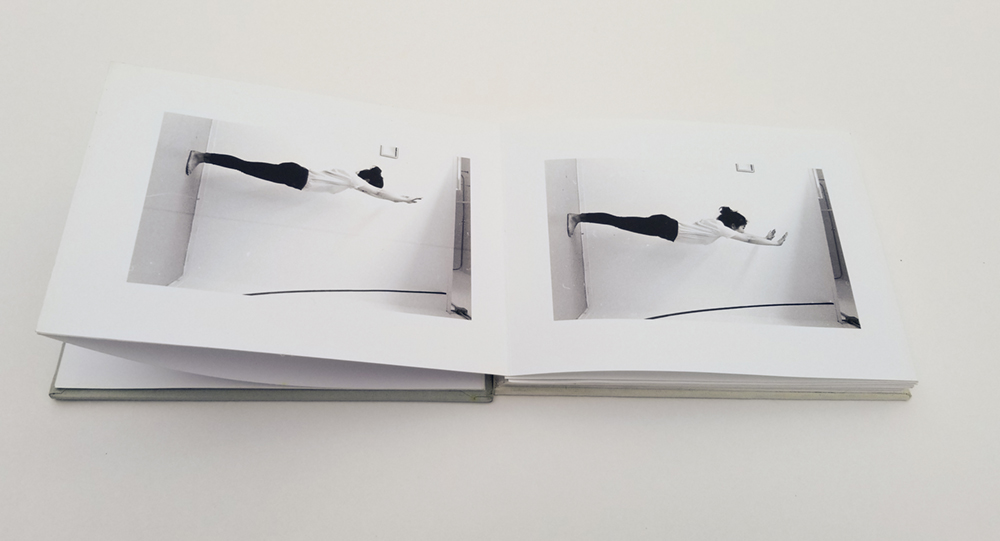

Nostalgically recalling conceptual photographic art of the 60’s and 70’s, Vito Acconci and Helena Almeida come to mind. Kioto uses herself in performative ways for the camera, the body becomes not only a sculptural form, but also a subject and object. Measuring the space of how images are hung on gallery walls to the height of her body or to the amount of seconds upon a 16mm leader film strip (Kioto is 8.875 seconds long). The natural body is mechanized through these imaginative generative ways of how her works are created and exhibited for us.

Kioto Aoki is a very resourceful artist, having a special ability to make work in any situation from anything around her. She has resuscitated old camera bodies through site-specific work as an artist in resident at The Museum of Surgical Science, to creating provisional pinholes from found materials with community members in the Tokachi Region of Hokkaido, Japan. Her unconditional approaches to photography have developed into a vernacular uniquely Kitoto’s. Her work puts on display the delicate volatility of the photographic process. In doing so, then, perhaps too, using these processes in turn tells of the fragility of the body. Faces are rarely if ever seen in her work. A blurry hand is reaching out of frame, feet suspend in mid air, and a bun of hair is pressed stark white against a rich black background. Kioto makes objects of quiet contemplation from history and the body. It is as Teju Cole once said that “objects , sometimes more powerful than faces, remind us of what was and no longer is; stillness, in photography, can be more affecting than action.” There is that wonderfully powerful stillness in Kioto Aoki’s work that I am effortlessly drawn to.

It is a true pleasure to have had the space to talk more in depth with Kioto Aoki for this feature.

Follow on Instagram: @photoandkioto

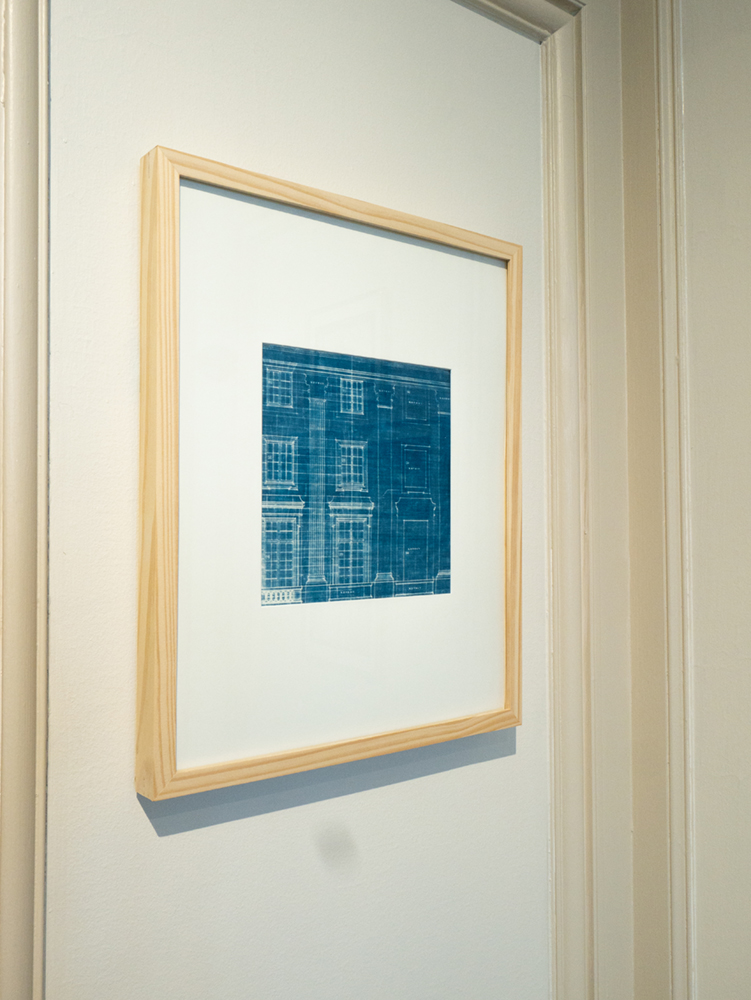

© Kioto Aoki, Installation view of first floor reception room of Breathe, Fibres of Papers Past at IMSS, 2021

As a musician and performer, do you feel these other creative aspects of your practice naturally sometimes come through in your visual work?

I’ve always seen my visual and music work as independent from each other. They have different origins, processes and are separate modes of creation for me. It’s been mentioned to me before by others that my image-based works have a kind of rhythmic sensibility that feels “musical,” but there is not a conscious effort to connect the two mediums so explicitly. I am not typically adding my own music to my films or photographing musical concepts, necessarily. Though funnily enough my producer for my second solo taiko album asked me to make a music video for one of the pieces, because he knows I make films but this is new territory and coming from a special request.

The concentricity of my musical and visual practices can be traced through more aesthetic, philosophical concerns. My approach to sonic textures are similar to my experiments in visual structures and there’s a durational component that both practices share, exploring nuances of repetition and change. The optical observations does not quite mirror, but runs rather parallel to, the auditory explorations of simple, foundational phrasings. There is an aesthetic quietude and stoicism with still room to play that I feel in both practices too.

I also recognize that an aspect of performance permeates both practices. I don’t think of myself as a performer per se, in the way that a dancer performs with their body. Nor do I feel that I actively “perform for the camera,” as has been suggested as well. But I do move in space with the camera and engage the image plane with my body to create particular visual compositions and cinematic experiences. Choreography is an important part of musical phrasing for how I understand my taiko playing as well. I often measure musical space and timing with my body through dance-like choreography. It’s both visual and audial. I do sometimes say I have a “performance,” or I’ll “be performing: when I am playing taiko though, which is more related to the idea of presenting something live in front of others.

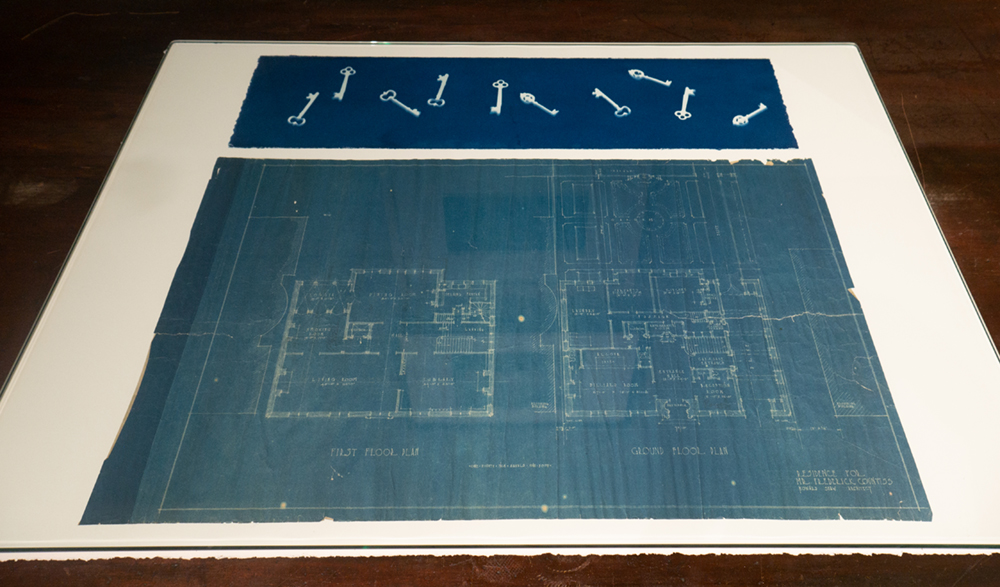

© Kioto Aoki, untitled [Mansion Keys] above original blueprint print of ground and first floor of Countiss Mansion, cyanotype, 2020

Architectural spaces make an appearance in your work often. Can you talk a little about this relationship you have to site specificity and the built environment?

I think as artists, it’s important to be able to contextualize your work to help understand (I use this term loosely) your practice. Site-specificity does this with a kind of immediacy and charm in its self-reflexive logic that I like. As a live music improvisor, I’m engaging with and communicating through gestures unfolding in real time; responding to what is happening directly around me. This might be an answer to your previous question too. Improvisation is an integral part of my music, but I also embrace this spirit in my visual practice, especially in the site-specific projects. My creative process often involves finding opportunities of perception within the immediate environment, like accentuating a shaft of sunlight, a crack in the floor, or the pathway of walking feet through a reframing of attention. It is this act of reframing that resembles an improvisational approach, via the recognizing, intertwining and accentuating certain qualities of a space where the work is produced and exhibited. Sometimes that means acknowledging architectural characteristics, other times responding to material or geographical histories. There is a beauty in the spontaneity and flexibility of these responses that offers a sense of playfulness that is in my work. I like this challenge or structure of working with the materials I have available to me at a particular moment in time.

In your project “Breathe, Fibers of Papers Past” a lot of historical and possibly personal narratives are interwoven. How did you navigate these stories in the work? Also, what was your process for re-activating found cameras and objects for this exhibition?

For this show, I knew I wanted to engage the site-specific histories connected to the International Museum of Surgical Science (IMSS) along with my own work related to the body and medical history.

The first is the history of the building that the museum is currently housed in. Currently a landmarked building, the mansion was originally built in 1917 for Chicago socialite and philanthropist Eleanor Robinson Countiss as a family home. The design of the house was inspired by the Le Petit Trianon, a chateau from 1770 on the grounds of Versailles that Eleanor visited during her travels to Europe. The funds to finance the home’s construction was provided by Eleanor’s father John Kelly Robinson, who made his fortune as an executive at The Diamond Match Company in Ohio. The company itself was originally founded by Eleanor’s grandfather and became the largest match manufacturer in the 19th century. I found and organized the original architectural drawings of the house and the subsequent variations through the final layout. So I created new blueprints (cyanotypes) from these original drawings by isolating some of the ornate details of the ceiling tiles, mirrors, cornices, or even the plumbing system. I call them “sectional cyanotypes.” I displayed the one original blueprint print (the image you see here) alongside my own cyanotype photogram of the remaining original keys.

The Countiss mansion was later acquired from the family in the early 1950s by the International College of Surgeons (ICS) founded in 1935 by surgeon Dr. Max Thorek. The goal of the ICS was to promote a global exchange of surgical knowledge. Initially conceived as the ICS Hall of Fame, the IMSS eventually expanded to become a repository for its growing collection (and Thorek’s personal one) of historically significant surgical instrumentation, artworks and manuscripts from surgeons, collectors and institutions.

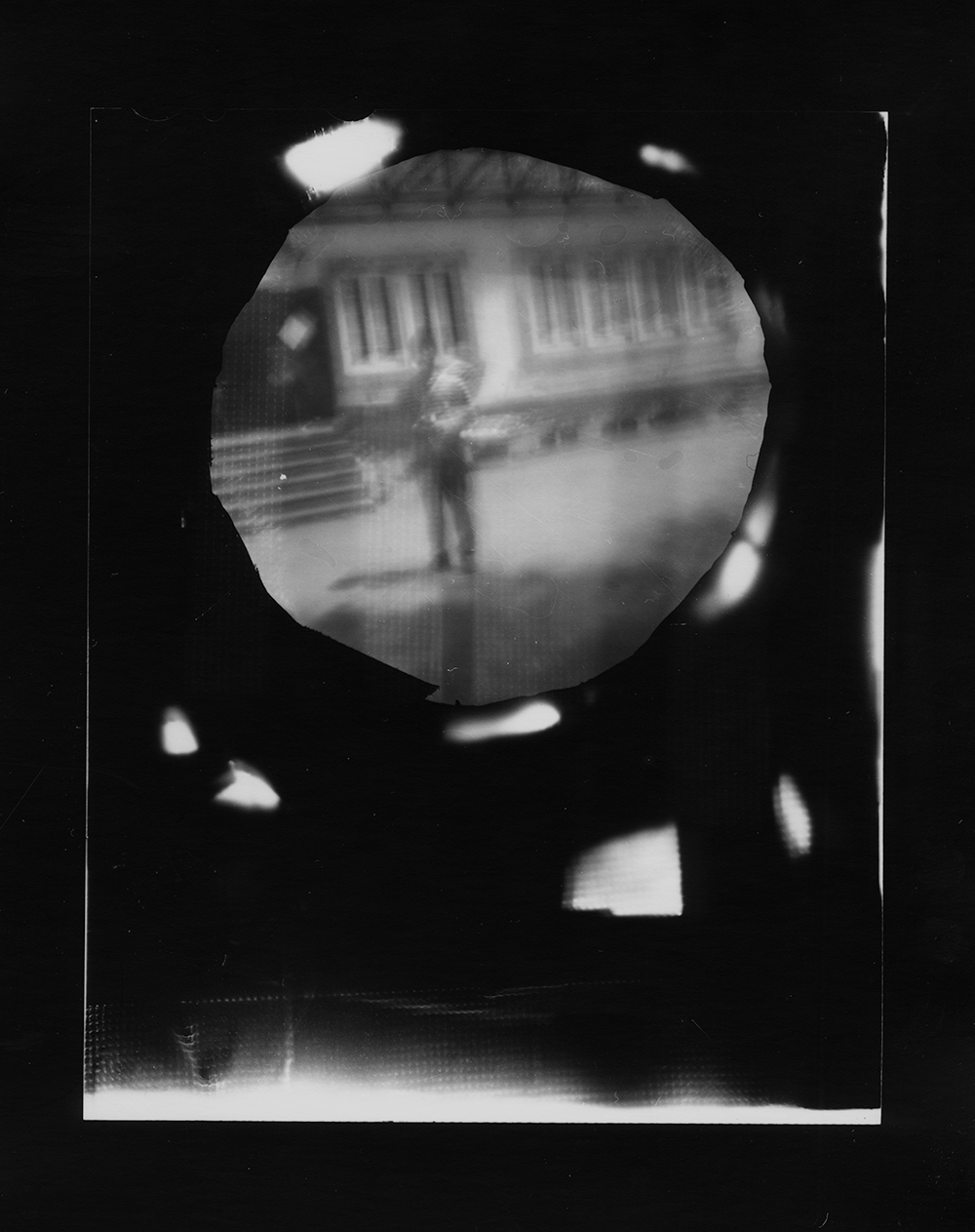

On the side, Thorek was also a quite active amateur photographer and had even published two photography books, which I personally sourced and purchased from a local Chicago used bookstore. In these books, Thorek was writing about the paper negative and aesthetics of Pictorial photography, the genre his own photographic work might be categorized as. For one of the bodies of work in the exhibition, I made a pinhole camera out of a tin Diamond Match Company box I found online and photographed the interior spaces of the home using paper negatives. I often use paper negatives myself, but this Diamond Tin series was a way of blending the narratives of Dr. Max Thorek and the Countiss residence.

The third aspect was to either incorporate or respond to materials in the museum collection. I found some of Thorek’s photo prints and awards from the many salons he participated in. Those objects were exhibited alongside his photo books on the first floor entrance hall. I also found a Henry Clay Camera from the late 19th century in a closet that most of the staff had not even realized was a camera, because it folds into an indistinct box. I took the camera up on the roof to photograph the view out onto the lake, with paper negatives of course. The house sits along the lakefront and I was imagining the different but perhaps similar horizon that the Countiss family looked out on when they lived there. That work is a collaged panorama.

In addition to these site-specific responses, I made other series of works that were somehow related to the human body. I used x-ray film, filled a whole room with photograms of my bun hung at my height, and made a series using relationship between the breath and photographic exposure. As a former gymnast and spending a lot of time in physical therapy or visiting the doctor’s for various injuries, I’ve always had an interest in anatomy, physiology and medicine. If I wasn’t in the arts, I would probably be an orthopedic surgeon or doing something related in the medical field. The exhibition took place through all four floors of the house museum, and I think I made 11 new works or series of works for the show. I integrating my own works, museum ephemera and additional objects throughout the various rooms and hallways so that you had to walk through the whole house to encounter the exhibition.

In あずりピン•ホール // pin•whole I see the improvisational nature of your musical background in jazz, and collaboration with the community coming forth as an educator as well. Then there is also the analog nature of photography too! This project is one of a visual poetic narrative I feel. How did this project develop?

That work came out of an exchange project that the non-profit arts organization that I’m part of and that my father runs, Asian Improv aRts Midwest (AIRMW) organized with the Tokachi International Exchange Center in the Obihiro / Tokachi region in Hokkaido, Japan. I went for about a month in summer of 2019 with another member of our organization to meet with local community members, ranging from artists to cafe founders, to learn about the social and cultural landscape of this more rural region. I knew I wanted to make some kind of portrait work but since traditional portraiture is not necessarily my style, I decided I would create a pinhole camera during the interview that my colleague was conducting, with whatever was available in the space. Then I would photograph them using that pinhole, so that the camera itself was also an individualized object.

The first half of this trip I was staying at Feriendorf Resort Village in Nakasatsunai, modeled architecturally on German Feriendorf holiday villages. I turned the first floor kitchen into a darkroom using black farming tarp to block the room. All the darkroom equipment was borrowed from a local photographer, Souda Seijiro, who I had worked with the previous summer on another itinerant darkroom in Obihiro. He had just retired his own analogue darkroom studio and lent me all of the enlargers, processing tanks, etc.

For the latter half of the project I moved to the town of Shikaoi, farther from the Obihiro City center. There I set up another darkroom inside an old neighborhood ramen restaurant kitchen. The ramen shop’s owners were elementary school classmates of the Tokachi International Exchange Center coordinator Tom Hanaki (our guide and co-producer for this exchange project) and offered their old restaurant space across the street from their current shop for my use.

The resulting images and cameras were then exhibited back in Chicago, alongside works by Obihiro / Tokachi area artists to culminate the summer exchange. Top left is of current director of the Nakasatsunai Feriendorf Village, Ryotaro Nishi. The ceramic pig is an incense burner with the Feriendorf logo and I added a backing area to hold the film. Top right is a camera made entirely from scratch, at a pony farm run by Michiko Harayama. At the time, she was just starting to build the fence around the land so the camera was made by splitting one of the leftover beams to make the frame and leather from an old saddle that was lying around to make the enclosed body. All the studs and nails were hers as well. The bottom set is from a visit with visual artist Masaya Shirayama who invited us to his home and atelier. This camera is made from an old paint bucket in his studio.

You allow the mechanics of photography to become visible, placing us inside a camera’s body it feels like. Can you speak to the relationship of your body to that of the camera’s? Do you think of the body as an apparatus not so dissimilar to a camera itself?

I often think about Plato’s emission theory, which suggested that human eyes essentially functioned like flashlights and projected light to see – instead of seeing the light from the sun being reflected from objects. It’s charming to visualize the eyes radiating light, like projectors. And maybe it’s not too far from what is happening. We may not physically be emitting beams of light, but as image-makers we do illuminate objects –by illuminate I mean accentuate– by bringing them into the frame. Within this analogy, the body could be seen as an apparatus framing our sightline much like a camera would.

In terms of the body-camera relationship, I do like the self-contained and self-reflexive structure of the artist both in front of and behind the lens.

It’s personal yet universal and accessible, I hope. A bit similar to why I love parietal and prehistoric art. Many prehistoric communities around the world left some form of the hand as either handprints or rock carvings. And there’s something so beautiful about that universal, initial gesture made by all homo sapiens. Not necessarily the actual gesture of putting paint on the hand then printing on the wall, but the gesture of leaving that gesture behind. It’s my (the artists’s) body within the frame but a hand could also just be a hand, a foot is a foot; the significance rests on the idea that it’s a human one.

I am not sure I quite see the camera as an extension of my body though. Nor am I trying to animate the camera by forgetting the body. I am aware that I am moving and dancing with the camera. The mechanisms of the body and the mechanisms of the camera can inform and engage with each other, in a collaborative manner. But I think for me there are always still two distinct entities at work within this collaboration: the body and the camera. In my most recent dance film, I was thinking about planes of perspective that the camera navigates. The film has three cameras and four bodies, playing with the shift of visual tenses between first, second and third person; making less rigid the lines of mover, dancer, camera-person, documenter. The camera is visible, the bodies are visible, the bodies working with the cameras are visible. So really, I feel that I am working within the space between the notion of the camera as an extension of the body and the body inhabiting a camera.

The analog processes you use in your work can require such physical labor. Do you think this physical act of touching the medium, of being so intimate with your techniques is what keeps bringing you back to them?

Absolutely. I am all for intimacy and tactility; the physical memory. The digital space does not offer those things for me, so I continue with analogue processes. There’s something about the slower pacing, time, and mode of thinking that I enjoy as well. I have to be more deliberate and considerate about certain aspects with analogue making. There’s also the fact that analogue textures cannot be replicated in digital formats and I happen to like those textures a lot.

As someone who has also taught photography for many years, research and working with students unwillingly at times informs my own making. Is there inspiration you find in the classroom as an educator that pours out or gets filtered to your own creative studio practice? Is there a favorite photographer or image you like to show your students in your classroom?

I am learning from my students always. I think most noticeably in how I talk about art or communicate what excites me, rather than a direct reflection in the work I am making. I teach at both an art university and a community college so the students’ interest, relationship to, and familiarity with art ranges dramatically. You have to respond to students and are in this constant exchange that feels like akin to improvisation. I’m constantly being asked to reframe certain ideas in a variety of arrangements, whether that’s through simple vocabulary or sequence of exposure to works. I find this exchange to be fun and challenging and being around art in these different contexts feels like a privilege, which in turn inspires me to continue making work. It’s a wonderful thing to have faith in art.

I often share filmmaker John Smith’s works in the film courses I teach. They’re short and concise, yet have this element of play with image, language and sound that’s still clever and abstract enough not to be too didactic. And Helena Almeida’s work, which naturally has to do with the body, material and image plane.

Daniel Hojnacki received his M.F.A from the University of New Mexico in 2022. He currently lives and works in Chicago, IL. Daniel is a recipient of several awards and residencies including The Penumbra Work Space Artist In Residence, LATITUDE Artist in Resident, Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention, The Patrick Nagatani Photography Scholarship, The Phyllis Muth Arts Award. He has exhibited work at the Museum of Contemporary Photography and The Chicago Cultural Center. Daniel has hosted public workshops and lectures with SPE Midwest Chapter, The Penumbra Foundation, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the Smart Museum of Art. His work has been featured in Phases Magazine, Aint-Bad and Southwest Contemporary Magazine

Follow on Instagram: @D_HOJNACKI

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026