The Dynamics of Photography and Disability: Nolan Trowe

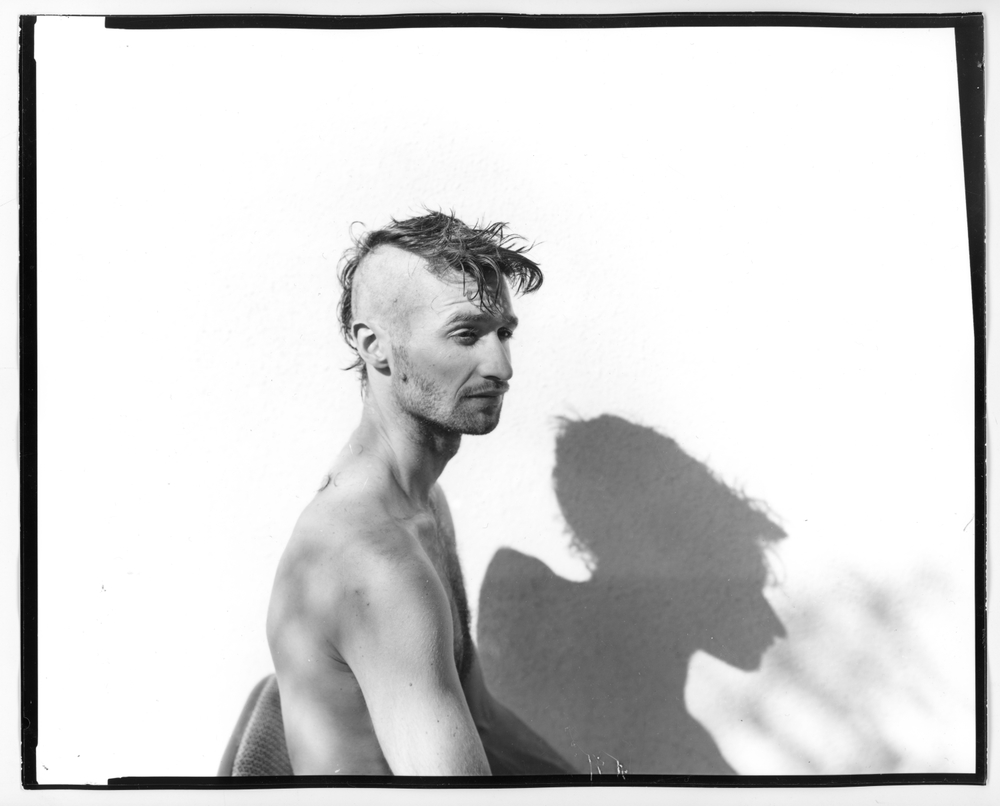

“Seven Years Later”, 2023, They say all the cells in your body regenerate every seven years. Now, I don’t know if that’s actually true, and I’m not going to look it up, because I like to believe it. It feels like every seven years, some major shift occurs. This is a contact print made from an 8″ x 10″ piece of orthochromatic film. Image: Nolan, who has light skin and brown hair shaved into a mohawk sits in front of a white wall. He is looking off to the side and is in a side profile of his face and body. His shadow is cast onto the wall next to him.

This week we are looking at projects by disabled/chronically ill photographers. The definition of dynamics is “forces or properties which stimulate growth, development, or change within a system or process.” Each of these artists is approaching their work in ways that embrace this meaning, enacting change and raising important questions about societal systems through their ideas, craft, and processes they use.

Nolan Trowe is a multidisciplinary artist from California. His work has been published and recognized internationally. The most recent of his many honors is being a 2024 Light Work Artist in Residence.

First-person statement:

I want my work to transcend the label of disability. While disability is a part of my identity, it’s not the summation of who I am or my art. I’m quite sick of the labels, to be honest. I’m not the token wheelchair user. I don’t want to be the “disabled” photographer: I just want to be a photographer. Disability is on the surface, but underneath is so much more. I hope my work can pull deeper at what it means to be a human being, regardless of any disability one may have. The five words I’d use to describe my work are love, shame, grief, joy, and fear. That’s what it’s all really about. Human emotion is what unites all of us. I just want to connect and relate to people. I hope people can see what I’m thinking and feeling, without a long, convoluted statement.

“Look at Me”, 2020, My wife and I pose for a self-portrait at the park by our house. She has my back more than anyone else in my whole life. She is always there to hold me up. Image: Nolan and his wife Jackie pose for a picture in the park. They are both in the background of the image with an expanse of grass in the foreground. Nolan is seated in a wheelchair and Jackie is standing behind him. She has light skin and is wearing a black dress. Behind them are trees.

MB: To start would you please tell us a little bit about yourself:

NT: I’m 30 years old at this point. I grew up in California. I grew up skateboarding. I still love it even though I can’t do it since my injury. I guess a lot of things have happened to me but that doesn’t make me who I am. I just feel like I want to connect with people mostly and I think that I try to be as empathetic as I can. I like to listen more than I talk these days. I feel somewhat confused about what it is that I’m trying to accomplish with my art, the ins and outs of that, or what is fulfilling. I’m trying to balance that with surviving. I don’t really feel like I’m what I do, or that I am where I live, or where I’m from. Those don’t feel like me.

I have been reading a lot and reading this one philosophical book – it says, and I don’t know if I fully 100 agree with it, we aren’t really anything. We’re not where we’re from, we’re not our family, we’re not what we do, we’re not any of the things in the world. When you strip it down, we are a consciousness that is aware of being a consciousness at its very core. That’s who I am. I’m not the voice of my head that talks to me and tells me what to say. I’m just sort of observing everything and I don’t know… It’s hard to try and put that into words.

I think it’s easier for people to digest that I am 30 years old, I’m a California kid, I am a skateboarder. Things people can associate with or put me in little boxes and try to make sense of me.

“Right There, It’s Okay”, 2020, I meditate on what happens when I die. Where does my body go, what about my spirit, what is to come. Will I find peace? Image: Nolan is lying on the ground in a garden. He is shirtless and his arms are crossed over his stomach. His eyes are closed. Above him is a tall sunflower bloom

MB: What does disability mean to you personally and what does it mean in your work, in your art?

NT: I feel conflicted with disability in my work because there’s this tendency for my work to just be seen as that. Disability, I’ve said this a bunch, it is a part of who am. It’s part of my existence because I do have a spinal cord injury, I am a wheelchair user, and there are real-life things I deal with because of my “disability” right? To some degree, it does inform how I move about the world, how I live, and my day-to-day life. I feel like this is just a part of me, it’s not who I am. It’s not the summation of who I am as a person. When I think about it I don’t even think my work is about this disability.

Disability is the surface, and in my work, what I really want to talk about is way beneath that. For me, that is the human experience, the human condition, or emotions. I’m just really interested in actually expressing emotions whether that involves disability or not.

Over the years, the longer I’ve had a “disability” or been a “person with a disability”, the less it means to me. There is so much more, it’s only part of it. When I did that thing with New Yorker, that’s real. You have a group of people protesting for this thing, and on the surface, it seems like it’s about disability but really it’s about dignity. I guess that’s what I’m saying – even though things might seem like disability on the surface, people are like “ I just want to have dignity, be seen as a person and I’m angry and upset and ostracized.” All of that to me, that’s what I think it’s about. It’s really just about dignity. And universally it’s things people need regardless of disability or if they are able-bodied, everyone wants dignity.

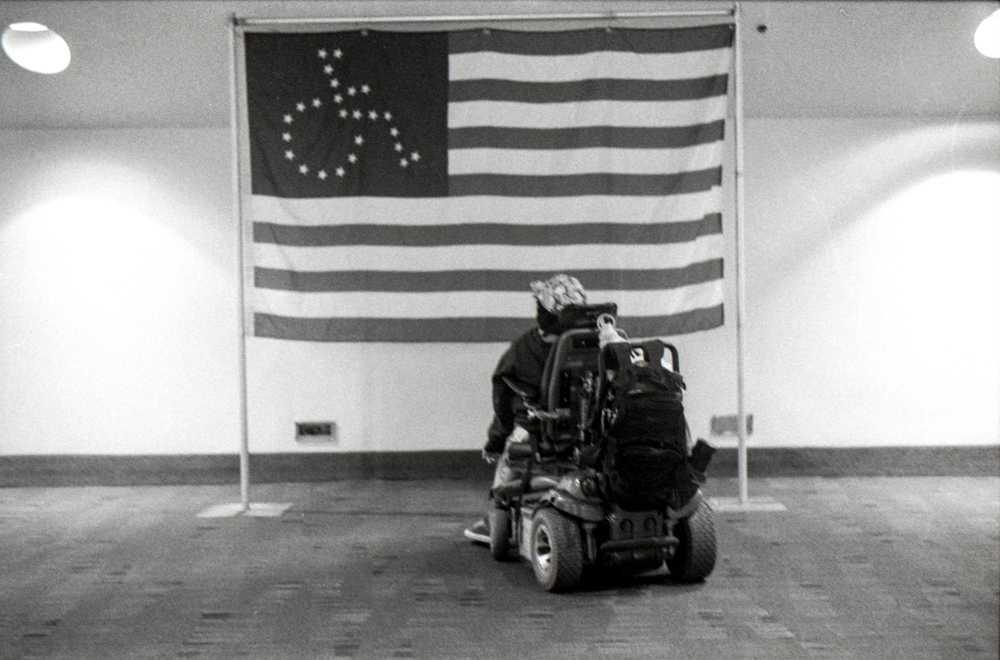

“DIY”, 2022, A young person, who uses a wheelchair, gazes up at an altered version of the American flag, repping the disabled community.

MB: You were just talking about that New Yorker piece, The Debt Ceiling Fight’s Collateral Damage. I first learned about you/your photography messaging with Tom Olin. I think you had or were making plans to work together. Can you share more about that experience – of being there at the protest with Tom and your sense of inheritance “the old guard having to turn over to younger folks.” Of photographing this movement?

NT: Tom is…I fucking love that dude, he’s awesome. It was really special. From what I understand of the history of ADAPT, they had their heyday in the 90s. It was super big and super strong, and then over the last couple of decades, it got whittled down, even more so with COVID. You had a lot of these OG ADAPT people who were there and they are getting older. It’s not as easy for them to go out for 12 hours a day after organizing the whole thing, after leading the marches, after being the ones to step up and be arrested, and then do it all over again. Anita, I think this last protest was her last one and she’s like one of the main OG’s. She’s just at the point where it’s too gnarly, it’s too hard on her body to just keep doing it. And a lot of the older folks, especially when talking about people with disabilities, it’s a lot of physical energy.

Meeting Tom, talking to Tom, and him being super open and stoked…He’s so badass. I don’t know how to put it but he’s just such a good dude.

It really did feel like this inheritance. For someone to have that belief and faith and trust in me to do that. I don’t want to say powerful because it’s a very trite overused word, but it was… I don’t know how to put it. You can get grants and awards and exhibitions, all of this stuff but being there and having Tom and other people say “It’s your turn and we believe in you”… meant more to me than anything. I don’t know how to put it because it feels so much bigger than the pictures or a publication. It was really profound for me to be there with him taking pictures of him. I have a bunch of photos I took of Tom at the protest. They’re not in the article, and photos of Anita and Nancy. All these people who have been in it for so long.

I don’t know if you’ve ever been in a moment where you just felt like you were part of history. At that moment, it was very surreal to be with Tom and see him get arrested. It felt like I knew this was important. It was really moving, I cried. It was gnarly, I brought a Super 8 camera and shot some movie film, but I haven’t put it out. I just have it. I remember I was in the hallway as people were being dragged out and I was filming and crying. That has never happened to me when I was photographing or filming anything. I’ve never cried. I didn’t even realize until after and my whole face was wet. Yeah, it was a super special moment for me in life, forget photography.

I have photographed protests and been in gnarly protest situations, this was very unique and overwhelming. It just felt like I was exactly where I needed to be which does not happen to me that often.

“My Ideal Body”, 2020, I understand that DaVinci’s “Vitruvian Man,” is supposed to represent the ideal or perfect proportions of a human being. I wanted to subvert this by including my braces and wheelchair, as a way to say that I don’t care about the typical or usual standards of what is “perfect” or”beautiful.” Forget all that. Image: Nolan recreates the Vitruvian Man through double exposure while seated in his wheelchair and wearing leg braces. He is against a white backdrop. In the multiple exposures, his arms and legs move outward recreating the poses in the drawing.

MB: I wanted to talk more about “the gaze” in your work, especially in Revelations In A Wheelchair. Both in terms of your vantage point when photographing from a wheelchair and also the gazes you encounter. From personal experience, I just really felt this project in terms of gaze and ways disability is or is not understood in public space. That push-pull of public/private/personal/political. I would love to hear more about this from you. And if photography was a helpful tool in this experience.

NT: Revelations In A Wheelchair – it was interesting doing that because I was still pretty fresh in my injury. It was 2018 so I had only really been disabled for 2 years. Before I moved to NY I guess I didn’t notice people looking at me as much. I was in the small town where my parents live and rehabbing up there, so I did not feel it as much. When I was in NY I think all these things sort of got highlighted. I just remember feeling like people looking at me all the time whether I was on the train, in the street, the grocery, someone was always looking at me.

When I first got injured I was pissed off all the time. I was so constantly mad and I didn’t really know how to express it. So that’s honestly where it came from. Being pissed off. I remember I used to kind of get off on the fact that someone started at me. I would point my camera in their face and they would get so uncomfortable. In my head, I would be like “Yeah fuck you! How do you like it?” And maybe that sounds messed up but honestly, that is how it felt. I was so sick of people looking at me. “How do you like it? Let me put something in your face.”

MB: It’s like flipping the mirror around or something.

NT: That’s sort of how it felt with the camera. That was almost how I would gauge if I would take someone’s picture. I was like “Okay, who’s the person staring at me today? Oh, you are.” I was so confrontational about it. I wouldn’t just take a quick picture. I would stop my wheelchair and aim it at the person, hold my camera up to my face, take a picture, and then just stay there. Sometimes people got super uncomfortable and left and other times it would become a stare-off.

Even today anytime I’m using my wheelchair or if I’m walking (I have leg braces and I use a cane) people are staring at my braces or staring at me walk. Now I’m not so angry about it. I had to work through it. That was a very therapeutic exercise because I was so mad and it was my way of dishing it back on someone in a very direct way.

I’ve spent a lot of time working through my shame, guilt, and feelings around my injury and my body. Now when that happens I’m just like “Yeah maybe they’re curious.” I don’t have time to get mad about it, it’s just a waste of time for me. If I got mad every time someone looked at me I would be miserable. And I think I was miserable when I wrote that essay. I was pretty mad all the time and didn’t know really what else to do.

I’m glad I’m not that angry anymore but I had to do it, it felt like the biggest fuck you in a good way. When it got published it felt so good. I always wondered if the people in the photo essay ever saw it. The people on the bench, the dude at the basketball court, the guy on the stairs, the parents with their kids in the stroller. I always wondered if they saw it and read it.

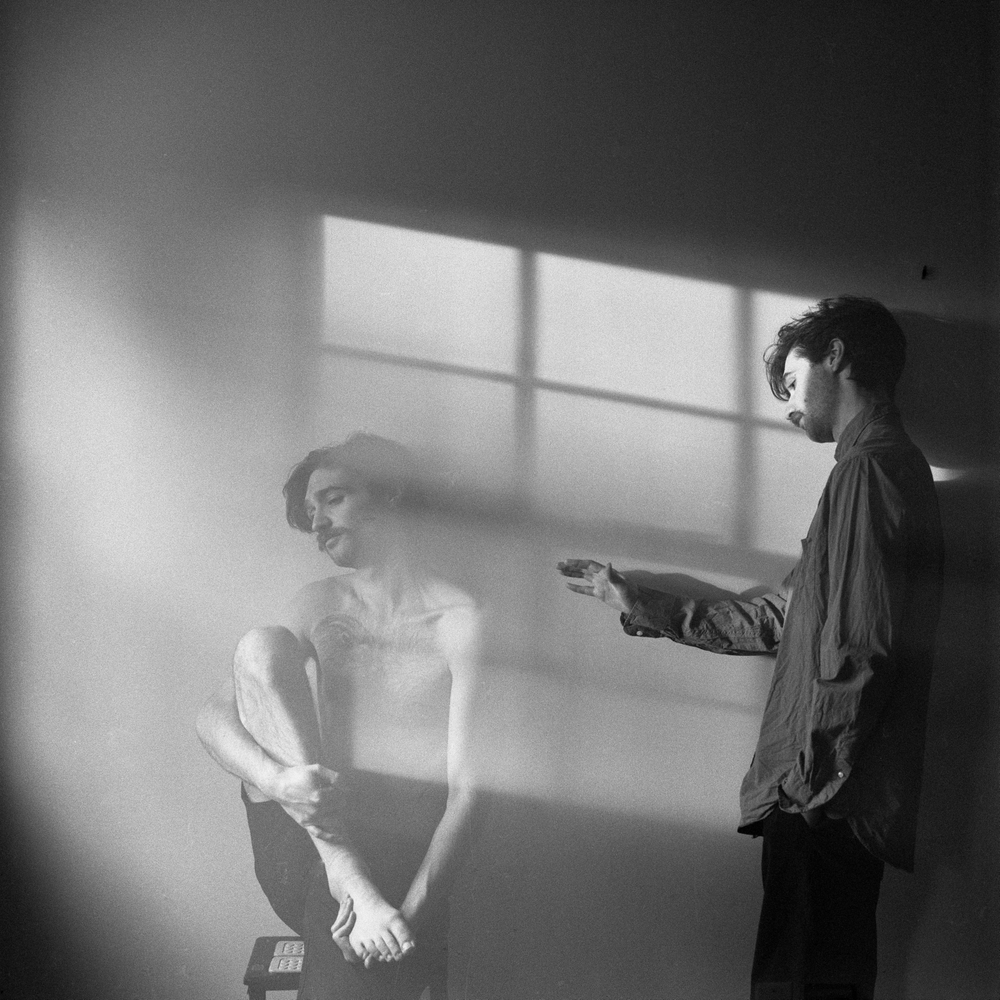

“Trying to Be Fine”, 2020, I feel like I’ve lived two lives, one as able-bodied and the other as disabled. With each passing day, I feel my old life drifting further and further away. My current self tries to comfort the past version of me. Image: A double exposure or composite photo with Nolan in two places. To the left he is seated on a stool one leg up against his chest. And he is looking down. His body fades into the image. Next to him is that shadow from window panes on the wall. On the right side of the image is Nolan in side profile reaching out toward the faded image of himself.

“Ain’t Nobody Prayin For Me”, 2021, A nurse at the hospital measures the amount of flexibility and atrophy in my ankles and legs, five years post spinal cord injury re-evaluation. Image: Nolan takes a picture looking down at his body while on a bed. His torso and shorts are in shallow focus and his feet are in sharp focus. A nurse leans over the edge of the bed touching his left leg.

MB: Has writing always been a practice alongside your photography? I am just really impressed with your writing and how both the images and text strengthen each other.

NT: No, it’s funny I’ve been a writer my whole life. It’s all I’ve ever wanted to do. I got my bachelor’s in creative writing. I always wanted to be a writer. I never had ideas of being a photographer, which sounds ridiculous. It was almost like an accident.

I enrolled in a class at NYU even though my master’s is in Experimental Humanities and Social Thought- not even anything to do with photography, it’s more like sociology. I took a photojournalism course during my graduate studies. When I took that class I was curious, I just wanted to mess around with photography and journalism.

I went to get my master’s so I could teach Higher Education, preferably English or Sociology. I didn’t plan on this whole photography thing. It’s weird how it happened. My whole life I just wanted to be a writer. I mean in high school I flunked out my freshman year. I was blowing it. I was getting arrested, doing drugs, all this shit. I remember my junior year of high school I had a teacher named Mr. Castille and we had this assignment, a creative assignment. He was like “You can do a book report blah blah blah or you can write 10 poems.” I did that.

I came into class the next week and he had it pinned on the front board of the class. He was like “Everybody I want you to come look at this work. It’s a really good example of a creative project.” After class, he came up to me and was like “You should do writing. You are good at this”.

I always want to have that as a part of my life. It’s been there way before photography was. It will always be there even if I put down the camera. I just think writing is so hard and that is what I like about it. Not that photography is easy. When I look at different mediums in my head I have a hierarchy of what’s harder. And when it comes to artistic things I always put writing at the top. To write something great, especially a book, I think that’s the hardest thing to do. I always aspire to be a great writer.

I love James Baldwin, and that’s why I think it’s so hard to write. When I make work I always think about my work not against, but in the same conversation as whoever else. When I make photographs I try to look at it in the whole conversation of photography. Everyone from the old school people like Duane Michals, Ansel Adams, and Gordon Parks, to contemporary young people, and freaking everyone. I just look at my work in the whole continuum. I want my work to be good enough to stand up there with the whole continuum of photography. I feel really confident with my photography. I think that it can stand up in the conversation of photography. I think I do interesting things that are worthwhile and I think I have something to add.

And then when I look at writing, it is just so intimidating. I think my pictures can stand up there with any photography that has ever existed. I just feel like that. But when it comes to my writing, damn dude, James Baldwin, his writing is so good. I can’t even fathom it.

So yeah writing has always been what I wanted to do. I still want to do writing, I write all the time. I write poetry and I am working on a manuscript. That’s the thing I care about the most is writing. I love photography, but man, writing, there’s something about it that I’ve always loved.

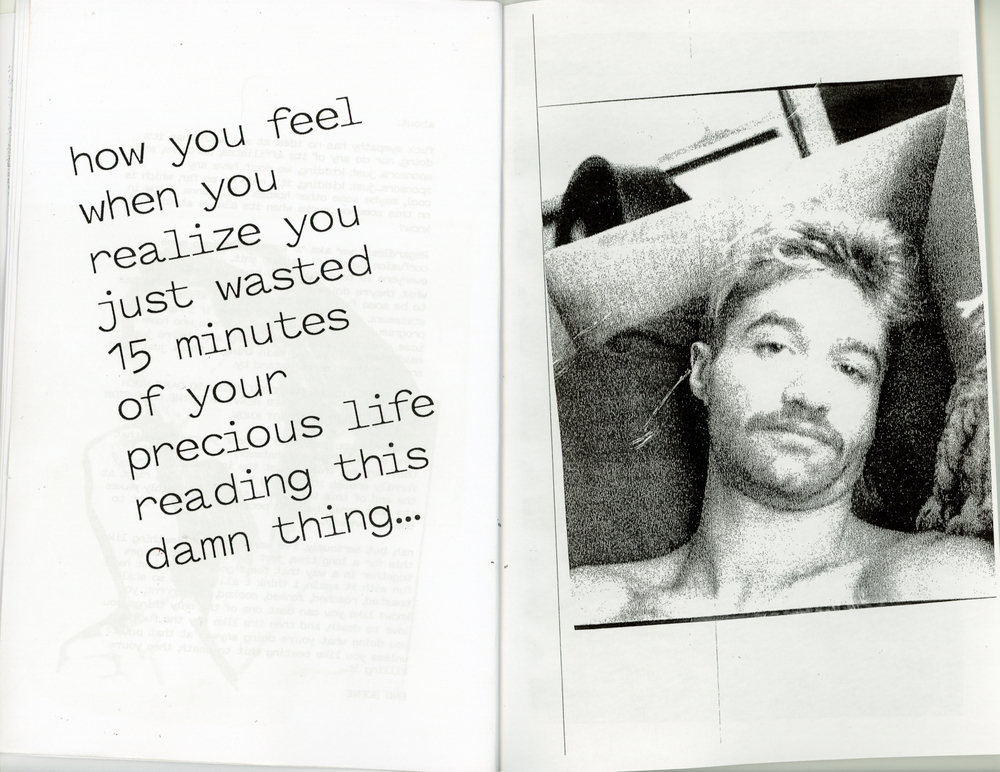

“Fuck Sympathy”, 2022, Selected spreads from the zine Fuck Sympathy. Image: A two-page spread from Nolan’s Zine. On the right is a self-portrait of Nolan on a couch. On the left is a large text “how do you feel when you realize you just wasted 15 minutes of your precious life reading this damn thing…”

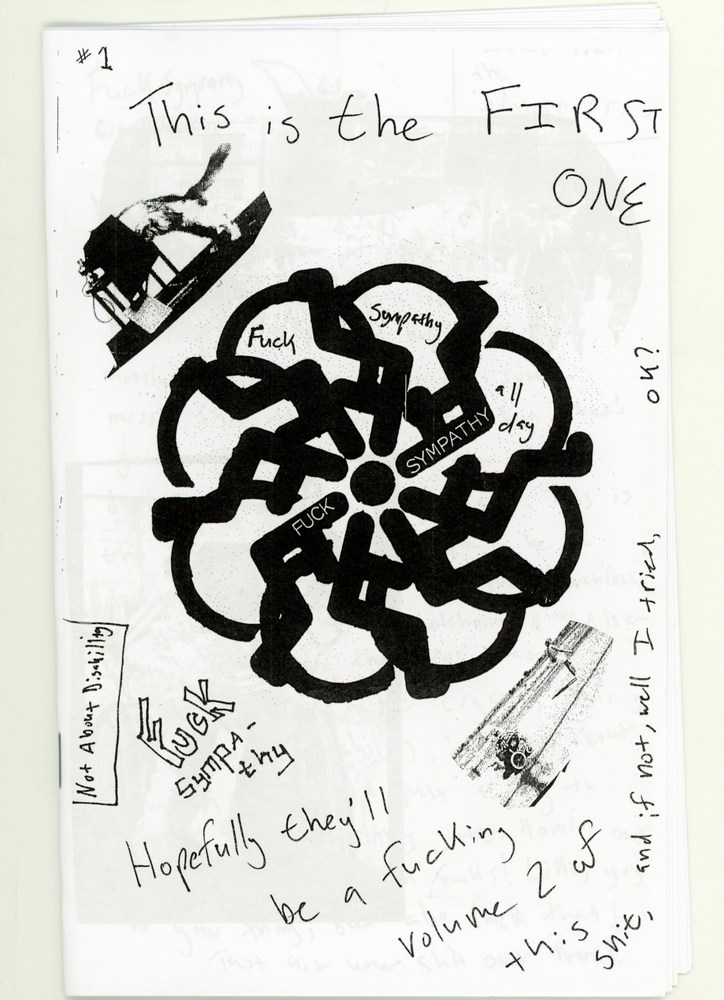

MB: Can you share more about your zines? What zines mean to you as artistic expression, as a tool?

NT: I grew up in California and skateboarding and I feel like it’s part of that ethos – skateboarding, lo-fi shit, zines, and just kind of like raw expression. I think I just got really bored with a lot of things I was seeing in photography. I was seeing all these clean expensive photo books, really perfect text, sequenced, everything lines up, you can tell that it’s done on a computer, and snap to grid.

I went to this portfolio review. It was super expensive and annoying because I was really broke at the time. I had to pay all this money to do this review and meet with these people and it felt so elitist, annoying, and expensive. Everyone was like “Oh my God, your 8×10 silver gelatin darkroom prints!” and I was like “Okay, what’s the opposite of that?” Let me go home with some printer paper, glue, and pens and make the opposite of an 8×10 darkroom print.

There are so many great skateboard zines out there or punk zines, all the old Slash magazine shit. That’s how I grew up. I grew up skating, going to backyard shows in Orange County and Los Angeles, and DJ’ing in Long Beach. I feel like somewhere along the lines that part of me got lost and I wasn’t expressing that through my art. And the zines were a place I could be angry again. In the zine, I say something like “ This is about feeling something. I don’t care if there’s typos in it or if it’s messy, or if it’s confusing, if it doesn’t make sense.”

That’s what I want. I need to express that piece of myself. I think since I had my spinal cord injury and I can’t skate board any more, in a way the zine feels like skateboarding. It’s my way to still do that or express that feeling of…you know John Cardiel would say “destroying something” or “leveling the place.”

What gets me excited about art is when people take risks and they are unapologetic. It’s like, I might not agree with you, that’s kind of intense, but I respect people who can go out and know that it might not be received well but if it feels true to them they’re going to do it.

I love work that’s just so raw. I crave it. That’s what I love about a lot of zines, is that they are very raw in their expression. And they are unapologetic. And they are a little bit intense sometimes, or ignorant or off the wall. But I’m here for it. I think it’s the most honest expression. Like Fuck Sympathy Vol 1, I think it’s the best thing I’ve ever made. If someone were to say “What do you do?” or “What represents you?” I would give them that.

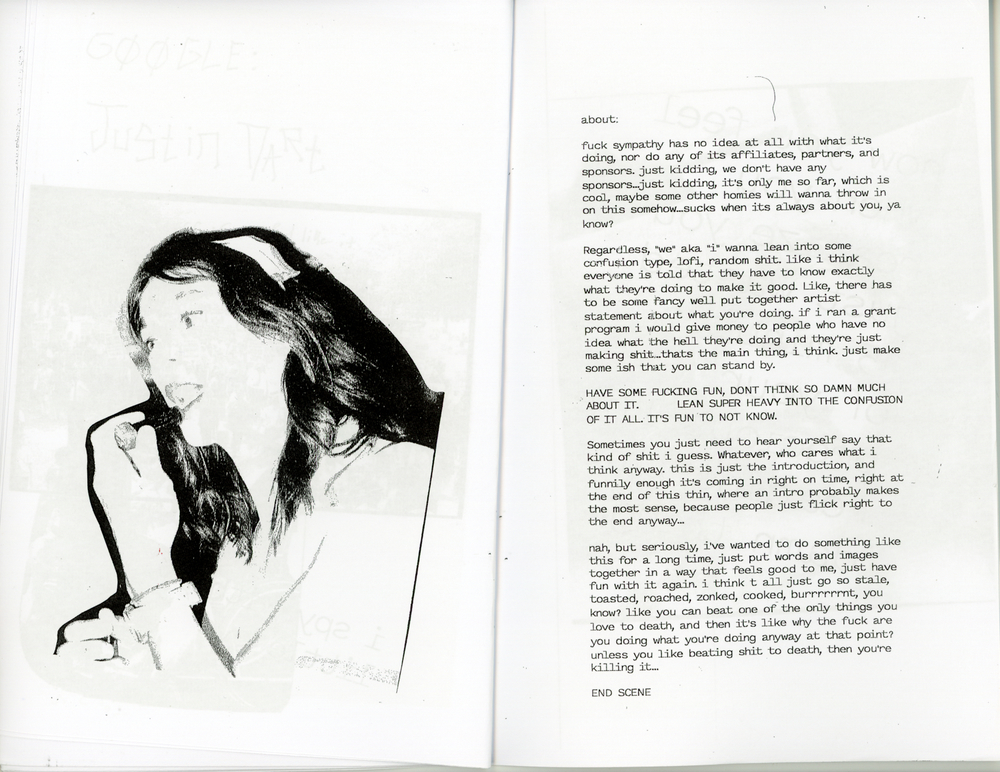

“Fuck Sympathy”, 2022, Selected spreads from the zine Fuck Sympathy. Image: A two-page spread from Nolan’s Zine. The left side has a photo of a person with light skin and dark hair putting on lipstick. On the right is a long text explaining what the zine is about.

“Fuck Sympathy”, 2022, Selected spreads from the zine Fuck Sympathy. Image: The Cover of Fuck Sympathy. In the middle is the access symbol of a figure in a wheelchair repeated in a circle, creating an abstract flower shape. The title is typed and handwritten and there is also text “This is the first one.” “Not about disability.” “Hopefully they’ll be a Vol 2 of this shit, and if not, well I tried.”

MB: I was wondering if we could talk about the title too, Fuck Sympathy. I mean in some ways it’s pretty self-explanatory but I didn’t know if you wanted to expand on that.

NT: It’s interesting because during this interview I realized I’m still angry, even though earlier I said I’m not angry (both laugh). I’m just finding healthier ways to express it and having more fun with it. So this has been enlightening because I realized “Oh yeah sometimes I’m still pretty pissed off.” – But like in a fun way.

MB: Anger can be a productive tool, I think.

NT: Honestly, when I think about it the best stuff I make is in response to something that I don’t like. Fuck Sympathy was made in response to that elitist and expensive portfolio review that I went to. I felt like “fuck this shit” Boom, here you go crappy zine with typos and curse words, kind of calling the photo industry out on itself. It was fun.

I got tired of fake shit. I appreciate it when people are real. Even if I don’t agree with someone or their opinion or they are rude – I would rather deal with someone who is a complete asshole but is entirely themself than someone fake. Because it’s like “Okay, I know who you are. That’s you. You’re not trying to be anything else.”

There were so many times when people would come up to me because of my disability and be like “Oh my god. I’m so sorry!” Even people I didn’t know, strangers, would come up to tell me how bad they felt for me. They want to pray over you in the grocery store next to the fucking salami. And you’re like “No. You can keep all of that.” Like fuck sympathy dude. There is such a big difference between sympathy and empathy. Sympathy is rooted in pity. It’s fake bullshit. Empathy is someone just really trying to hear you out and connect with you and be where you’re at. Sympathy is not for the other person, it is selfish and it’s for that person. It’s fake and it’s bullshit.

Even beyond disability, I feel that so much in the art world. You know, gatekeeping stuff and people who are like “Oh that’s so and so.” Who cares if that’s so and so? Are they a good person? In the art world, it feels like you pay-to-play with money. Money can buy you portfolio reviews, workshops, Master’s degrees, or MFA’s because there are not that many fully funded programs. And this is just my opinion but it feels like so much of it has to do with how much money you have and who you know.

And that’s not the whole art world. There are some awesome people in the art world too. I want to be frank about that. But I guess it comes back to skating. Like when I was a kid and you skateboarded the only way you got respect was by your skating. If you love skating, genuinely. There’s no way around it, the only way to be good at skating is to fall. You have to fall a lot. You get hurt. And the people who aren’t really about it are gonna quit. That’s the way it is, there’s no workaround and I just miss that.

So I guess Fuck Sympathy is about not just the art form of the zine but how that relates to punk rock, hip-hop, skateboarding, DIY community stuff, and accessibility. That’s the other thing, I was selling prints for so much but I can sell a zine for 5 bucks including shipping. All my homies who are super broke and still working at the gas station can afford to buy my zine. And those are the people I make the work for anyway. It felt like this homecoming of like “Oh yeah, that’s who I am.” I have so much fun making the zines.

![11_TROWE_Lover(revoL[ve])](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/11_TROWE_LoverrevoLve.jpg)

“Lover (revoL[ve])”, 2023, I use the 8×10 camera specifically to explore my sexuality and intimate relationship with my wife Jackie. It’s a new language I’m working with. Image: Nolan is looking at the camera and Jackie is leaning against him, her bare back to the camera. He has one arm around her.

“Yes”, 2023, A contact print of an 8″x 10″ piece of orthochromatic film. Exploring the nature of dominance and submissiveness in our relationship. Image: Nolan is on the left side of the frame in soft focus in a white dress shirt. Jackie is seated and looking directly at the camera, also in a white dress shirt. Nolan’s hand is holding Jackie’s chin/face and Jackie’s hands are resting in her lap.

MB: Who are some of your influences or what is some work that is really speaking to you now?

NT: My friend Kyle Chavez, that guy influenced my life so much. The way he approached life was on his terms and watching him skate was so sick. He was just so in tune. In high school, he would screen print his own t-shirts. He was the best skater. I miss that dude so much. He had so much influence on my life and my heart. I think people strive for that and he just…it was effortless for him. I feel so lucky I got to be his friend. His memory inspires me so much.

My homie John, Johnny Detweiler, he passed away too. He was such a sick skater, good tattoo artist, and painter. The other day I was going through his Instagram. It’s the only record of his art that I have. He tattooed my chest, so I have a piece of his art on me forever. I’m so glad about it. I was looking at all his old drawings and doodles and was like “This is so so sick.” It got me so excited.

Someone alive who inspires me is my friend Cheney Orr. He’s a sick photographer and a good homie. I think the people who inspire me the most or influence me the most are my homies, people I’m actually in conversation with.

People beyond artistic shit and are just dope people – My friend Joe Giordano. He’s from Baltimore and is a photographer but even beyond his photographs he’s such a sick person. When I hang out with him it makes me want to make things. My friend Gabrielle Baez, she put out a photo book last year and she’s from Puerto Rico. We were in the Magnum Foundation Fellowship together. We talk all the time and her work is so sick. People who influence me the most are people who are part of my life in some way.

People I haven’t met…One of my favorite skaters ever is Heith Kirchart — he goes to the beat of his own drummer. I feel like it’s so easy to tell when someone is who they are and are not trying to be anyone else. That to me, more than any other thing, whether it’s like a musician – Ahamd Jamal or Bill Evans or a skater who does it their own way or photographer – a Mark Gonzalez type of person – you know there’s no front. They are not trying to be anything or do anything that’s not them – for better or for worse. My wife Jackie, dude she’s so sick. She doesn’t give a fuck dude – in the sickest way, not in an ambivalent “I don’t care” way. She just really honestly doesn’t give a shit what anyone thinks about her because she’s so in tune with who she is.

That’s where I want to be. That’s the kind of stuff I want to make or who I want to be as a person.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026