Review Santa Fe: Harvey Castro: Los Olvidados

©Harvey Castro, On a damp and misty morning, Jorge Suc Ical, with his family by his side, climbed a mountain overlooking their new home to perform a traditional Mayan ceremony in honor of the Nahual, Noj. These ceremonies pay tribute to the ancestors and implore them for guidance and protection.

Today, we are continuing to look at the work of artists with whom I met at Review Santa Fe in November 2023. Up next, we have Los Olvidados by Harvey Castro.

Harvey Castro (b. Nicaragua) is a documentary photographer and multidisciplinary artist who employs a variety of mediums, including still and moving images, audio recordings, and historical content, to delve into the complex relationship between climate change, migration, identity, and inclusion.

His work is deeply personal, drawing inspiration from his experience as an immigrant and person of color to create genuine connections with the people he photographs. Castro captures intimate moments that reveal the emotions, thoughts, and feelings of those he photographs—depicting their struggles with adversity and exclusion and moments of joy and camaraderie within their communities.

Based between Oakland, California, and Mexico City, Mexico, Castro continues to use his art to advocate for social change and raise awareness of critical contemporary issues.

Follow Harvey on Instagram: @harveycastro.co

©Harvey Castro, A semi-truck belonging to the sister of Jorge Suc Ical was destroyed and washed away off the main road and now sits on a small creek eight months after the landslide.

Los Olvidados

On November 5th, 2020, a landslide triggered by six days and nights of constant rain brought on by Hurricane Eta buried the village of Queja in San Cristobal Verapaz, Guatemala, along with an estimated 58 people. Within a few days, the municipality’s mayor, Ovidio Choc Pop, declared the area a “campo santo,” an uninhabitable graveyard ending all rescue efforts and recovering only eight bodies.

Guatemala’s poor infrastructure significantly impacts the highlands, home to farming and indigenous communities. When natural disasters occur, they destroy houses and roads and uproot the crops that provide food and income for these communities. Those left with nothing often migrate North to the US, chasing “The American Dream”, further risking their lives. The US does not have a policy recognizing climate refugees, making their situation even more precarious.

The 2020 hurricanes, Eta and Iota, had the most impact on Central America, affecting approximately 7.5 million people and forcing Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala to declare states of emergency. I saw parallels to my experience documenting the stories of families recovering from the aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico nine months after landfall in June 2018. According to the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, 135,000 people relocated to the states within six months post-Maria.

These stories are a powerful reminder of marginalized communities’ ongoing struggle in the wake of natural disasters. Their plight highlights how a lack of equity and representation leaves them without effective agency, struggling to survive and rebuild. It is essential to remember that natural disasters have a lasting impact, and we must provide support to ensure that communities can recover and thrive. By highlighting these stories, I hope to bring attention to the need for action and change in the face of climate-related disasters.

©Harvey Castro, November 5, 2021, marked the first anniversary of the landslide that destroyed the village of Queja. Before the tragic landslide, close to 300 families lived in the village of Queja. When the village was declared a “camposanto,” a graveyard, making it uninhabitable, most of these families relocated to Nuevo Queja, a short 30-minute walk through the mountain that separated them. Only 20 families stayed behind due to a lack of resources and assistance.

Daniel George: Following Hurricanes Eta and Iota, you became aware of the plight of these communities. Would you share more on your motivations beginning this work and documenting these people and their circumstances?

Harvey Castro: The motivation behind this work goes back to February 2006, five months after Katrina had made landfall in New Orleans. I had just left my job in New Hampshire as Sr Director of Operations and Supply Chain at a labware manufacturer and was driving cross country to San Francisco. My experience in New Orleans shaped the direction for my work today.

Twelve years later, California was experiencing record-setting fires. I had just left my job in the software industry, and nine months had passed since Puerto Rico was devastated by two back-to-back category 4 and 5 hurricanes, Irma and Maria. In June 2018, I traveled to Puerto Rico, where the Los Olvidados series began. The people I met, the stories I heard, and the work we did collectively solidified my commitment to this project.

In 2020, California was going through another record-setting fire season, and back-to-back category 4 and 5 hurricanes, Hurricanes Eta and Iota, made landfall in Central America. Drawing on my experience in Puerto Rico, I knew I wanted to expand the project and focus on the effects of these natural on migration. In August 2021, I flew to Guatemala and started to work on the second chapter of Los Olvidados.

©Harvey Castro, A portrait captures the solemn expressions of Ofelia Ical Jom (14), her younger sister Dora (3), and their grandmother Matilde Tilon. The girls tragically lost their parents and six siblings in the landslide and now find solace in the care and support of their grandmother and uncle as they navigate the aftermath of such a devastating loss.

DG: This work addresses the broader issue of how marginalized communities are more negatively effected by climate change and extreme weather events. In what ways do you feel your photographs contribute to the potential for action, and ultimately change?

HC: The name of my series is Los Olvidados, which translates to The Forgotten. When I enter these communities, the cruise ships are already docking in San Juan, and tour buses are already driving to Antigua from the airport in Guatemala City. Life has gone on.

While working in Puerto Rico, I shared the pictures and story of Angel Gonzalez, a blind 84-year-old man living alone without running water or electricity, with Caridad Sorondo and Betsy Collazo, two community leaders I collaborated with. When they saw Angel’s living conditions, they initiated a direct-action mutual aid campaign that changed Angel’s life in weeks. Another byproduct of these catastrophies on the affected communities is the decline of mental health, Angel committed suicide just over a month after we met.

One of the fundamental principles in the Theory of Constraints used to measure operational effectiveness is identifying the constraint and understanding that constraint is critical for improving the effectiveness of a process. In my experience, infrastructure is the weakest link and prevents assistance from reaching these communities in the aftermath of these disasters. Whether the affected community is in a first-world or a third-world country, when the roads collapse, or the water system gets contaminated, there hasn’t been a plan b.

I hope my photos provide a reflection point. With everything happening worldwide, it’s essential to be an active participant.

DG: Tell us more about your interest in using a combination of still and moving images, as well as audio in your work. What do each of these mediums contribute to the narratives that you share? With this sort of work, I’m always curious about depicting the struggle of others in the correct manner—to advocate rather than exploit. How do you navigate all this?

HC: As a storyteller, my goal is to communicate with my audience, and knowing that we all learn in different ways, visual, auditory, experiential, etc., by expanding my practice to include these mediums, I’m also growing my audience. For my solo show in Mexico City last year, I made large, 13×19 (A3+) cyanotype prints on fabric that people could hold and expand to see the full image. I also installed a blue FEMA tarp on the ceiling to create an atmosphere similar to how some survivors in Puerto Rico had been living for months.

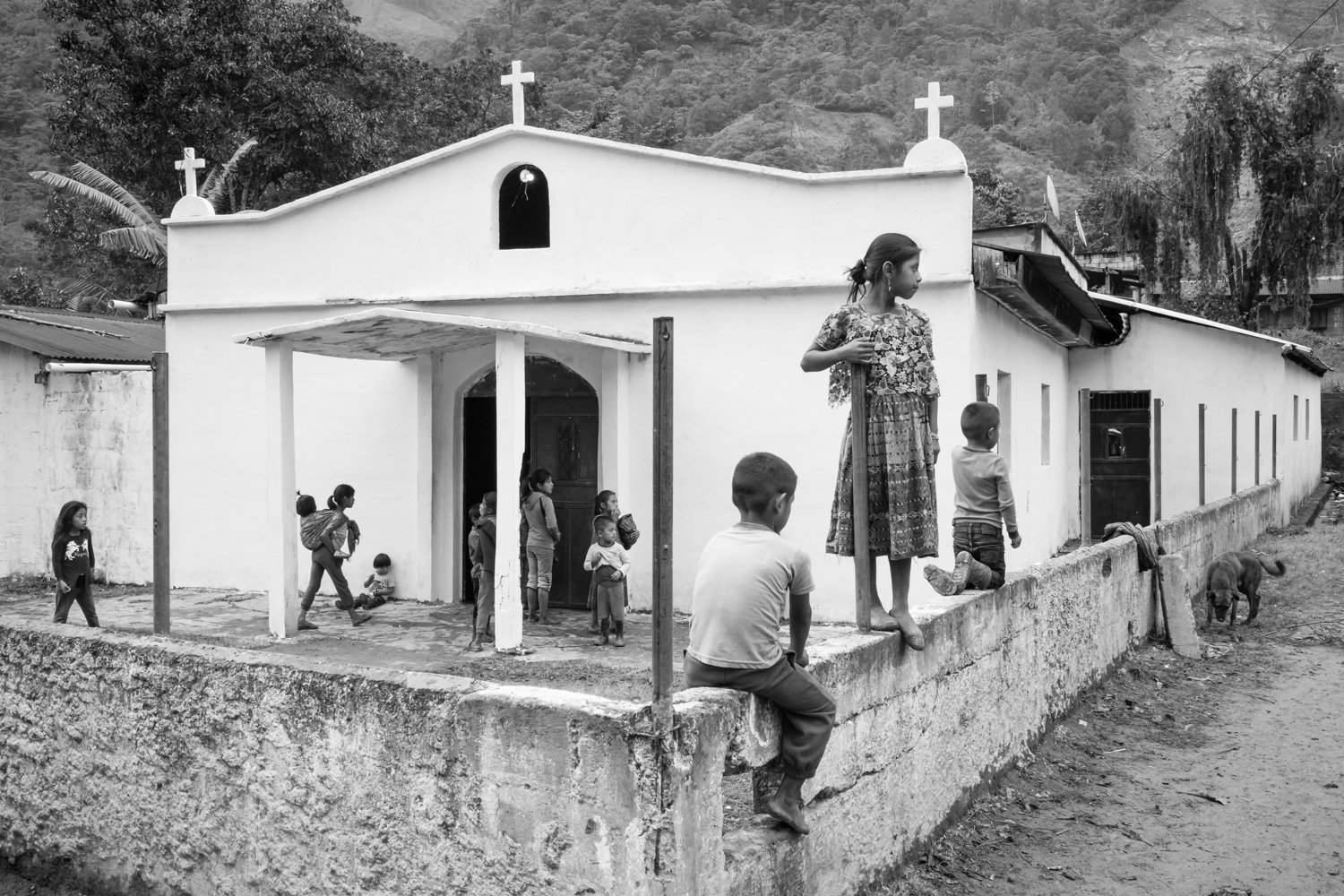

For Los Olvidados Guatemala, all the photos are in black and white, with very few references to the modern day. You can assume they were from long ago if you didn’t read the statement. However, the accompanying video opens with the voice of VP Kamala Harris, followed by the voice of former president Donald Trump. To me, the echoing in their sound bites represents what I and other immigrants have been hearing in the US for as long as I can remember, regardless of the administration: the promise of immigration reform. So, while the photos are traditional, black and white, the video is experimental and allows me artistic freedom to express my personal views.

In June 2021, around the same time, VP Harris was in Guatemala, telling people at a press conference not to come to the US/Mexico border; I was teaching a photography workshop for migrant students at a high school in Novato, California. One student from Guatemala shared with us that it was important for him to document his life through photos so that his future generations would know him. Back home, his family didn’t have a camera, so he never met his grandmother, not even in photos. I was that kid in 1982.

My mother and I left Nicaragua for the US three years after the triumph of the Nicaraguan revolution and amid the contra-revolution. When I look at photos from Susan Meiselas, I see myself reflected in those photos; I could be one of those boys or bodies in the streets. In one of my photos from Guatemala, a little boy is peeking through the wood slats of a house while the adults are on the side congregating. That curious little boy is also me; it’s still me. The work is always personal. I’m not advocating for these people; I’m advocating for us.

DG: In your biography you mention drawing on your personal experiences “as an immigrant and person of color to create genuine connections with the people [you] photograph.” This is certainly felt in your images. Would you expand on this idea (on drawing on experiences to create connections), and why you feel photography is so well suited for the task?

HC: I’m only a person of color in the US, and where I am in the US will determine if I’m Mexican, Cuban, Dominican, or Puerto Rican, and I’m an immigrant everywhere I go. However, when I show up at an indigenous community in Guatemala, I look more like the oppressor than I do a native; it’s crucial to understand this—I’m not going in guns blazing like a cowboy out of respect for their history and the trauma that history has left behind. You have to be humble.

I was eight years old when I came to the US. I learned to speak English in about six months and became the official translator at home. When I started working in the labware industry as a materials manager, the company had just implemented a new production planning system. Since most production workers were Spanish speakers, I provided systems training and became the bridge between them and management. Ten years later, I started working at a software company, implementing and helping design features for the first on-demand warehouse management system. These 20+ years of managing people, systems, and processes, coupled with my personal story, have given me the soft skills to navigate these communities with the necessary sensitivity and maturity.

I’m still translating, except now I’m using a visual language to communicate laughter, pain, resilience, and hope through my photos; these are universal. That’s why photography is so well suited for this. Technology has made it so that even in some of the most remote places, people can still access a mobile phone with a camera, a mobile browser, and apps to access information that can help them explain their situation better or share their stories. I hope my photos inspire that little boy in Novato, California, to continue documenting his life for all future generations.

©Harvey Castro, On the first anniversary of the tragic landslide that devastated the village of Queja, claiming the lives of 58 residents, mourners gathered at the unveiling of a plaque in honor of the victims. The memorial, located in Aldea Queja, Guatemala, bears the names of those who lost their lives in the disaster and serves as a reminder of the tragic event that occurred on November 5th, 2020.

©Harvey Castro, Fifty-one bodies are still missing. Among the missing are Irma Quiac Sis, wife of Gregorio Ti Cal, and their two daughters Daylyn Mayerly Ti Quiac and Melany Mileydi Ti Quiac. The landslide claimed the lives of 58 people. Due to the dangerous terrain and continuing heavy rain, all rescue efforts ended when the village was declared a “camposanto.”

©Harvey Castro, On the first anniversary of the devastating landslide that destroyed the village of Queja and took the lives of 58 residents, mourners gathered at the unveiling of a memorial plaque bearing the victims’ names. Among them, a young boy peered through the wooden slats of a small store that sold drinks and snacks, now a haunting reminder of the tragedy that occurred on November 5th, 2020.

©Harvey Castro, Every month, on the day of the corresponding Nahual, Jorge Suc Ical and his family gather for a traditional Mayan ceremony. Here, a village elder leads the family in prayer to the Nahual Noj, which represents the transformation of knowledge into wisdom and experience.

©Harvey Castro, At the time of the landslide, Jorge’s wife, Sonia, was pregnant and at home with their other children while Jorge was at work. Here, Jorge holds his baby while the village elder leading the Mayan ceremony blows rum out of her mouth at the back of his head as part of one of the rituals performed during the event.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Lee Gap-Chul: Conflict and ReactionJanuary 14th, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026