Review Santa Fe: Bailey Quinlan: A Day at the Lake

Today, we are continuing to look at the work of artists with whom I met at Review Santa Fe in November 2023. Up next, we have A Day at the Lake by Bailey Quinlan.

Bailey Quinlan (she/her, b. 1991) uses photography as a tool for activism and connection, sharing vulnerable stories and highlighting injustices with compassion and urgency. She strives to create ethical portraits, and resonant landscapes, that show the interconnectedness of all people with each other, nature, and the infinite cosmos.

Quinlan is a 2023 Camera Lucida Critical Mass Finalist, winner of the Female in Focus award by the British Journal of Photography, a Flash Forward Festival Top 100 Winner by Magenta Foundation, received Honorable Mention in the Julia Margaret Cameron Awards for Women Photographers, and has work featured online by PhMuseum, Der Grief, and Velvet Eyes. Quinlan has a BFA from Tufts University and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. She lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.

Follow Bailey on Instagram: @bailey_quinlan_

©Bailey Quinlan, Portrait of my grandmother in her 20s standing outside a lumber company, taken by my grandfather on Ektachrome slide film.

A Day at the Lake

The content of this project explores the concepts of time, loss, and memory. With my grandmother as the main subject, we had the opportunity to travel to her hometown in Ashland, Wisconsin two years before her passing. We stayed at nearby Kern Lake, where she spent her summers as a kid, sleeping at the same old small cabin her family- she the youngest of eight- used to stay in. All her nieces and nephews and their kids spend summers there to this day.

Doing what any new wife in the 1950’s was expected to do, she left everything she knew and loved at the age of 20 to follow my grandfather to Connecticut where he was from, despite his lack of familial connection and the abundance of work opportunities for the lumber industry of which he was a part in the Great Lakes region.

Whenever she recounted her childhood in Ashland her face lit up as if it were some magical place. These distant memories, however, are disjointed from the small midwestern town that exists today. Not only did repeated recollection of the same stories likely alter her memories, but her entire generation has passed on, and most places have changed considerably over time- for instance, her elementary school has been converted into an apartment building, and the remote dirt road to the lake happened to be paved for the first time while we were visiting.

The last few years of my grandmother’s life were comprised of idleness, waiting, and reflecting. Contrastingly, the imminence of death is something that I, being in my 30s, cannot intrinsically understand because I have only ever looked to the future. So when my grandmother told me she was ready for “the long sleep,” it was rather jarring. When I started this project I struggled with the fear of loss- of people I love, and my memories of them. But through the course of making these images, and learning to appreciate her comfortable relationship with death, she slowly taught me how to embrace loss. “A Day at the Lake” captures my grappling with this process photographically, as well as adding to the ever-present dialog of how photography can both enhance and alter memory.

©Bailey Quinlan, Tire swing on the edge of Kern Lake. The branch has fallen in the water since then.

Daniel George: Tell us more how this project started. What prompted you to begin working with your grandmother on A Day at the Lake?

Bailey Quinlan: My grandmother was a musician, and in the final years of her life she was working on a collection of poetry and music for children that she wanted me to create images for. The writings were inspired by her childhood summers on the lake, and the title of the project (which I plan to co-publish by both of us in book form) is borrowed from one of her poems.

She was 89 years old when we first started taking photos together, and we knew it would probably be her last trip back home. Eight years later, and I never could have known how much this project would help me understand her, and process her death.

©Bailey Quinlan, Spread from a storybook my grandmother’s family used to read from all the time, found at the old cabin on Kern Lake.

DG: In your artist statement, you write that you learned to “embrace loss” while working with your grandmother on this project. I’m curious to hear further insights on this idea.

BQ: I began this project in my 20s- my grandmother being my last living grandparent. In the final years of her life, she was in a lot of pain due to arthritis, and she was very alone; her husband, all of her friends and siblings had long since passed. She told me she was ready to die. She was very comfortable with death, having a deep faith that reassured her, she spoke candidly with me about it, asking me to photograph her obituary portrait, and telling me what music she wanted played at her funeral. It was hard for me to hear, as I sat there on the edge of her bed tearfully- selfishly wanting her to stay around forever.

As I’ve gotten older alongside the development of this project, I have a greater sense of my own mortality, and a different relationship to death. I’ve come to understand death is just a part of life, and all we can do is be grateful for the time we have. Her final years I lived in fear of her dying, but I can now look back with gratitude that she lived such a full life that she was ready to die when her time came.

©Bailey Quinlan, Deer shot by my grandmother’s brother Bob, mounted in the old cabin across from where I slept.

DG: I am interested in your use of imagery and transcriptions to tell this story. Why was it important to you to expand this work beyond the visual—and include a written component, as well?

BQ: In the same way that a photograph can never tell the complete story- memories are lost with the beholder. My grandmother was the matriarch of my family- the last alive of her generation. She was the only one who could tell first-hand accounts of our family’s history, identify ancestors in old photos, and read the illustrative script of old letters. She had a nearly photographic memory up til the very end of her life, and she constantly told stories from her childhood, even reciting poems word-for-word that her father used to read to her.

This project was my attempt to preserve some of that, but to also add to the discourse of how possible it even is to preserve history. What gets lost over time, in the long game of cross-generational telephone? We have our ancestors to thank for our existence, but even if we find a blurry dusty image of them, what can truly be known of them? What can we understand about ourselves from even our own portraits?

©Bailey Quinlan, My great-great grandfather Abe Lincoln Biglow operated a telephone company on the top floor of this building on Main Street in Ashland, WI. His son, Crague (my grandmother’s dad) also worked there with him. (My ancestor Samuel Biglow, a judge, was appointed by President Abraham Lincoln, and therefore named his child Abe Lincoln Biglow. ALB also named one of his sons Abe- my grandmother’s uncle.)

DG: You also mention that this work seeks to investigate photography’s ability to enhance and alter memory. Certainly there is the characteristic of preservation inherent in the medium. How would you say that it alters memory? In what way do these images alter your memory?

BQ: In contrast to my grandmother’s memory, I personally struggle with my own- it’s something that drew me to photography as a medium in the first place. I am able to remember much more readily when I photograph something- partly because I have the record to reflect on, but also because in the moment, I paused to study the way the light fell or to contemplate the composition. Photography is my way of being present in the moment.

When I started the project, I was an observer- I had a familial relationship to the place, but I had no physical memories of my own there. My images were akin to William Christenberry’s process of revisiting locations and reflecting on changes to landscapes and buildings over time, as well as Alec Soth’s environmental portraits of people he happens to come across.

After my grandmother’s death I continued to develop the project, and my relationship to the place began to change. As I became more familiar and immersed myself in researching my family history I was able to find a deeper connection. My images shifted from an objective documentary style, to something more subjective and poetic. The imagery became reminiscent of Rinko Kawauchi’s everyday observations of the natural world, and Vanessa Winship’s long-term projects searching for the ethos of a place. I began incorporating archival images and objects into the work, and even inserting myself into the memories of my grandmother. I’ve always been told I look like her, and I even currently have the same hairstyle she did at my age. The performative elements of the images further underscores the slipperiness of memory. It’s a way for me to fold time- to connect with her across the boundaries of time and place.

This project was truly healing. It helped me to process her passing before it even happened. It opened doors of possibility instead of closing them. My memories of her are now encoded in these images.

We often use photos as evidence of what happened, but are they any different from memories? What we choose to hold on to, how we choose to frame it, and what we hope to forget- it can never be the whole truth.

©Bailey Quinlan, My great-aunt Anne (my grandmother’s sister) diligently researched our family history in her old age. This was one of her notes from the family archive. George Anne Szarkowski (John Szarkowski’s little sister) was Anne’s best friend growing up. They all walked to school together, and my grandmother sat next to John in band practice- she played the oboe, he played the clarinet.

DG: Regarding your broader photographic interests (as well as this project), what motivates you in your depiction of “the interconnectedness of all people with each other, nature, and the infinite cosmos?”

BQ: In the context of this project, I think it’s important that we tell our personal stories. There’s a line of thinking that for art to be strong, it has to be universal- that it should appeal to a wide audience. But I believe it’s the specificity of perspective that makes art resonant, and relatable. Everyone had a grandmother, and everyone has dealt with loss. In showing my investigation of these themes, I hope I can encourage others to do the same.

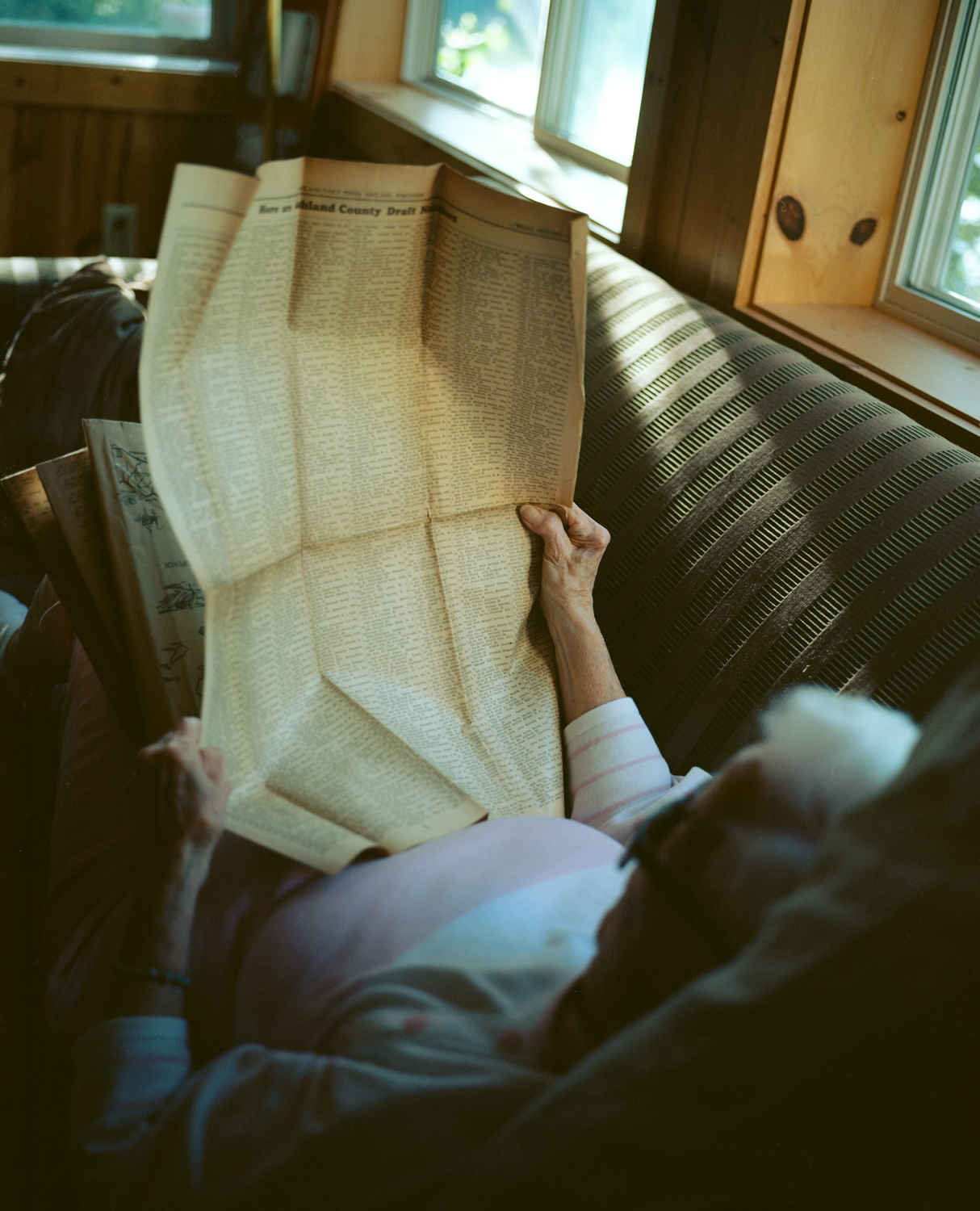

©Bailey Quinlan, My grandmother looking through a newspaper that her brother Bob who served in WWII kept, that listed the Ashland County Draft Numbers, looking for school mates names she recognized.

©Bailey Quinlan, My aunts Mary Barbara & Suzy (my dad’s cousins) calling my cousins back into shore on Lake Superior

©Bailey Quinlan, Concrete bust my aunt Jennifer (my dad’s cousin) made in college, left outside in the driveway of the old cabin

©Bailey Quinlan, The firing range where my grandmother shot her first shotgun. She didn’t know to keep it against her shoulder, so when she fired it kicked back and she thought she broke her arm. As she told it, she “wasn’t friends with that crowd anymore after that episode.”

©Bailey Quinlan, Wet beach towels with gnats caught in a spider web on the close line in Aunt Pat’s front yard.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.