Mexican Week: Felipe “Chito” Tenorio

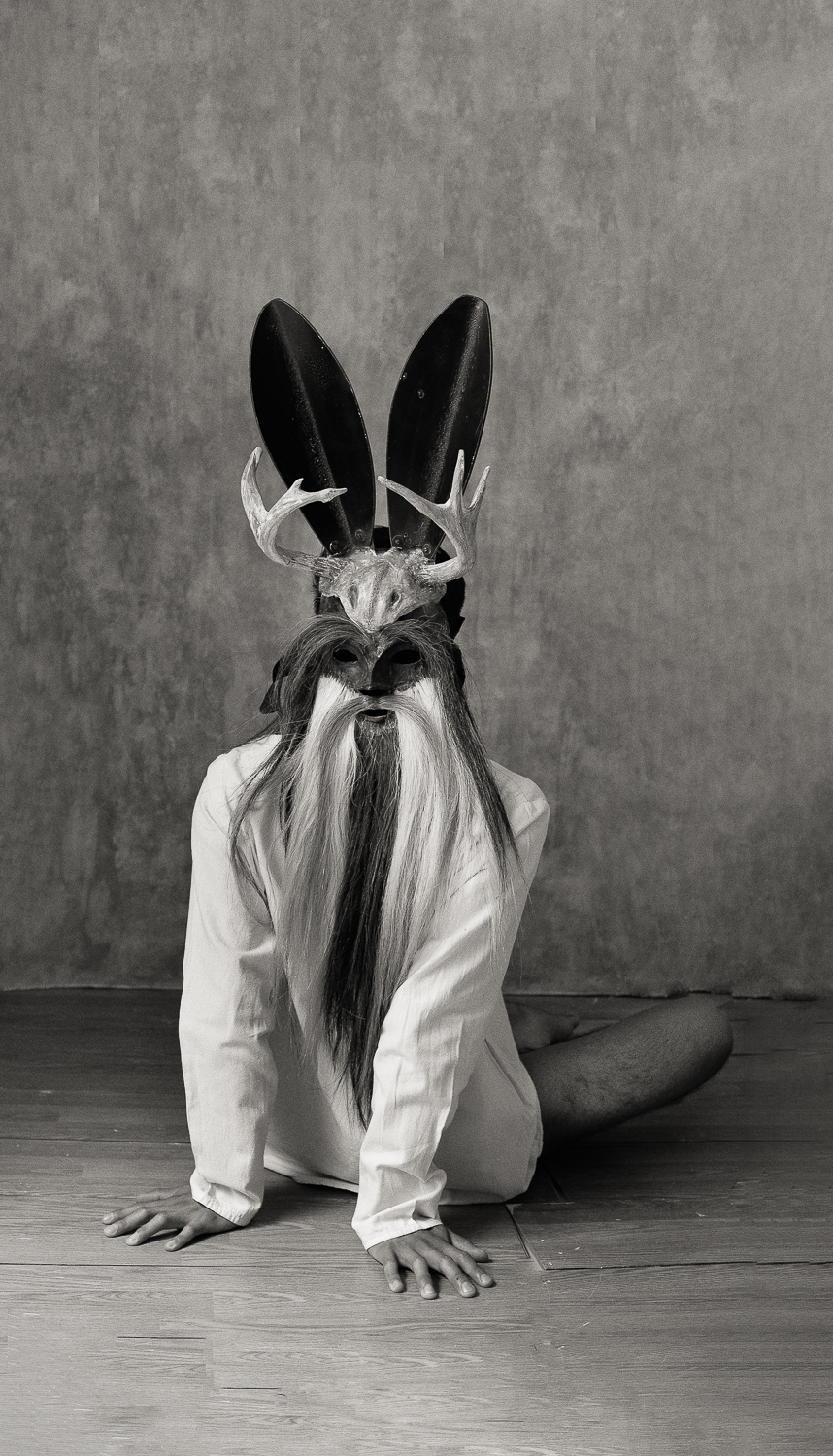

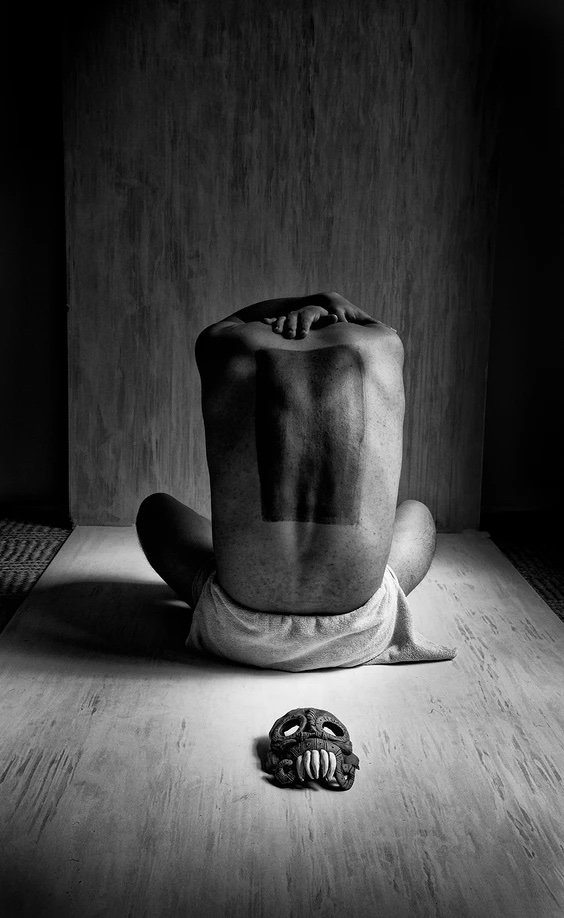

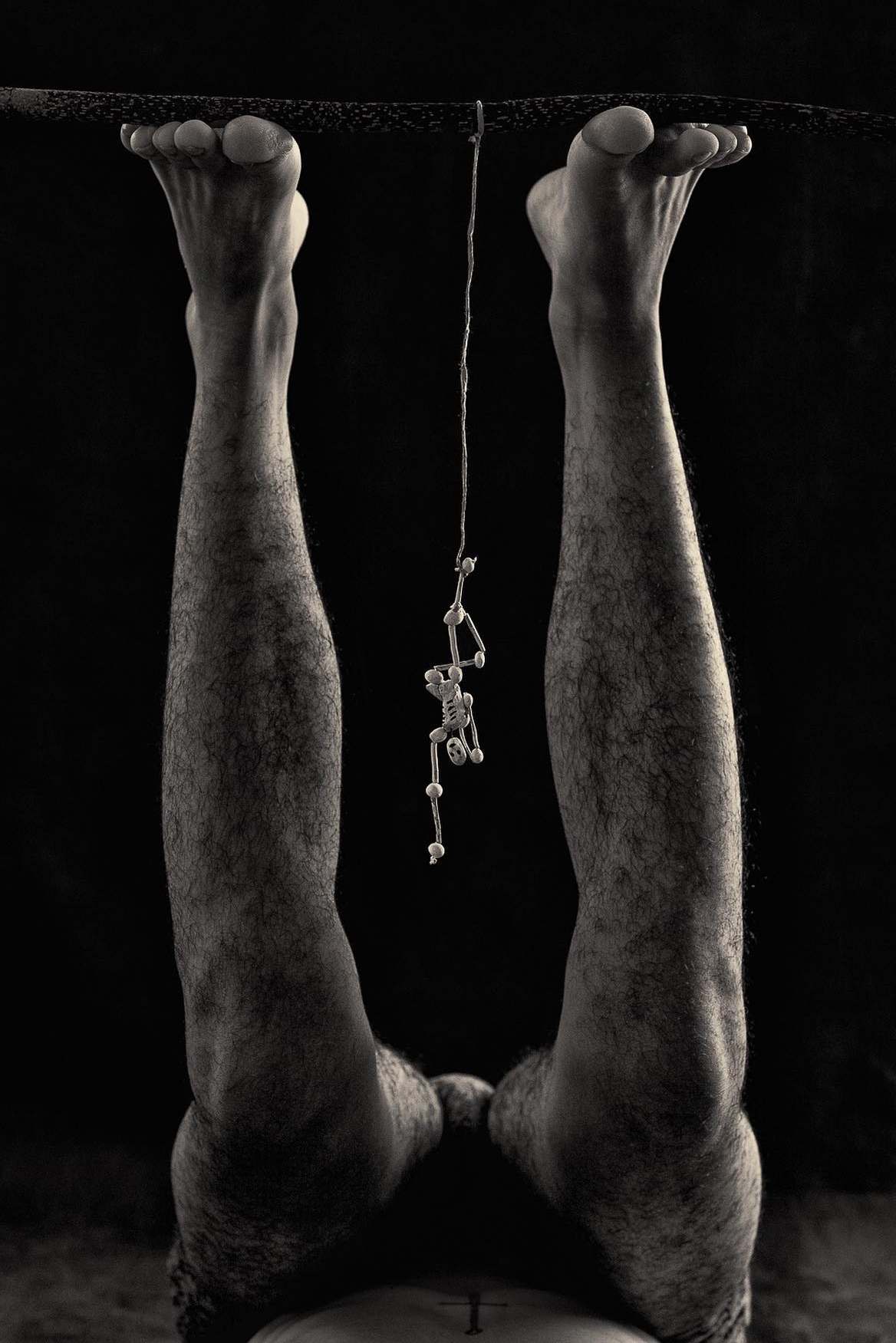

The opening interview of this six-part series on contemporary Mexican photography kicks off with a bold and traveled spirit. With nearly two decades of transformative immersion in Indigenous and artisan communities nationwide, Felipe “Chito” Tenorio’s artistic influences encompasses a rich array of myths, traditions, and visual culture from both Mexican past and present. Recent and painful personal experiences have paved the way for the artist to embark on a heart-wrenching exploration of loss and overcoming, giving rise to his latest work in progress, VIA DOLOROSA. In the project, fragmented bodies direct our attention to themes of mourning, spirituality, and new masculinities, but above all to the turbulent yet regenerative metamorphosis of our identity after the death of our most beloved and close ones. The photographs are highly emotive and poetic, all conveyed elegantly through conceptual simplicity. More profoundly, VIA DOLOROSA is Tenorio’s most personal work to date, giving us a captivating and generous glimpse into the most intimate stages of his unfolding grief.

— Vicente Cayuela, Latin American Editor

Editor’s Note: The following interview has been condensed

and translated from its original Spanish version

for accessibility to a wider audience.

He began his artistic exploration at an early age, with painting, music, and visual arts serving as his primary means of expression. It wasn’t until his teenage years that photography became an integral part of his perceptual diary, viewing it as the most direct form of understanding, connecting, immortalizing, and capturing the essence of individuals—a sentiment he continues to uphold to this day.

For over 16 years, he has resided in various indigenous communities in Mexico, where celebrations, mysticism, rituals, and roots have shaped his identity, imagination, and inspiration. He has undertaken diverse photographic projects aimed at honoring and promoting indigenous peoples and artisans in southern Mexico.

Currently, he remains actively engaged with artisan groups, teaching arts and expression in his city, pursuing studies at the Active School of Photography. He is also involved in the Risk Zone Seminar and actively contributes to the development of projects in authorship, artistic education, and art therapy.

Follow Felipe “Chito” Tenorio on Instagram: @felipe_chito_tenorio

VC: You have lived in indigenous communities in Mexico for over 16 years, immersing yourself in their celebrations, mysticism, rituals, and roots. In which communities have you been, and how has this experience impacted your artistic practice and understanding of indigenous culture?

FT: I have had contact and established relationships with many indigenous communities throughout the country. However, as part of an artistic project and for an extended period, I lived in Chiapas, in the southern part of the country. Among the communities I lived in were Zinacantán, Chamula, Pantelhó, San Juan Cancuc, Tenejapa, and Chalchihuitan. It was a process of rediscovery and rebirth, a way to cleanse oneself from “modern savagery” and reconnect with spirituality and more refined values. I consider these elements very present in the daily lives of the indigenous peoples of my country; they are immersed in their forms of expression and way of life. This generates a continuous and permanent visual and mental stimulus resulting from the combination of various artistic expressions (textiles, floristry, pottery, dyeing), rituals, and social aspects. It creates a comprehensive immersion that allows seeing life from the integration of a thousand explosive, “secular,” and creative elements. This has certainly been a mastery of creativity, development, and knowledge of techniques, symbols, and creation for a long time.

VC: What motivated you to undertake these projects, and how do you believe they contribute to the preservation and dissemination of local cultures?

FT: There are various projects primarily focused on the lives of grandmothers (bearers and transmitters of knowledge) and the work of women with artisan professions. These projects narrate and document the correlation between the history of women, their textiles, their techniques, and the impact of these on their community and time. My motivation was the search for the re-dignification and equality of Mexican Indigenous women and the rescue and documentation of ancient techniques that are in danger of extinction. This intersection perfectly contributes to satisfying that personal motivation rooted in an issue of both traditional and contemporary Mexican society.

VC: What challenges have you faced when documenting and sharing the stories of indigenous peoples through your photography, and how do you address these challenges in your work?

FT: I am very grateful for life because, considering the natural complications of integrating into an indigenous community (as a non-native), the bonds formed have been very honest and beautiful, which has neutralized these difficulties. The one that comes to my mind the most was a situation where I was asked not to publish any further information about a topic related to ritual facial painting, or I would be banned for life from the community.

Regarding the most significant challenge, in a community where the presence of men and women in the same space is prohibited, photographs are not well accepted due to beliefs about the soul and ritual modesty. However, in that community, the relationships with families were so close that they allowed me to photograph some female leaders (women of authority under their customs), their daughters, and granddaughters in a room by myself. Ultimately, I believe difficulties are part of the adoption process. I think the key is always to have a humble, teachable, adaptable heart that is equally as passionate and crazy about their vision of life as they are. This allows one to become invisible and be just another member of the community.

VC: How do you find the balance between respecting the traditions and rituals of the indigenous communities you photograph, while simultaneously sharing their beauty and diversity with a broader audience?

FT: Undoubtedly, I have encountered and grappled with this issue. For me, the balance comes through the interplay of my direct relationship and contact, the knowledge they impart to me, and collaborative work. My photography in this context seeks to be as faithful as possible to the self-representation that each individual or community perceives. Following this guideline, I capture the moment, and consequently, I feel that it is this same charge of personal steadfastness that naturally manifests their beauty, creating solid contrasts of diversity and richness. It is about learning to photograph with their eyes and communicating it through my language.

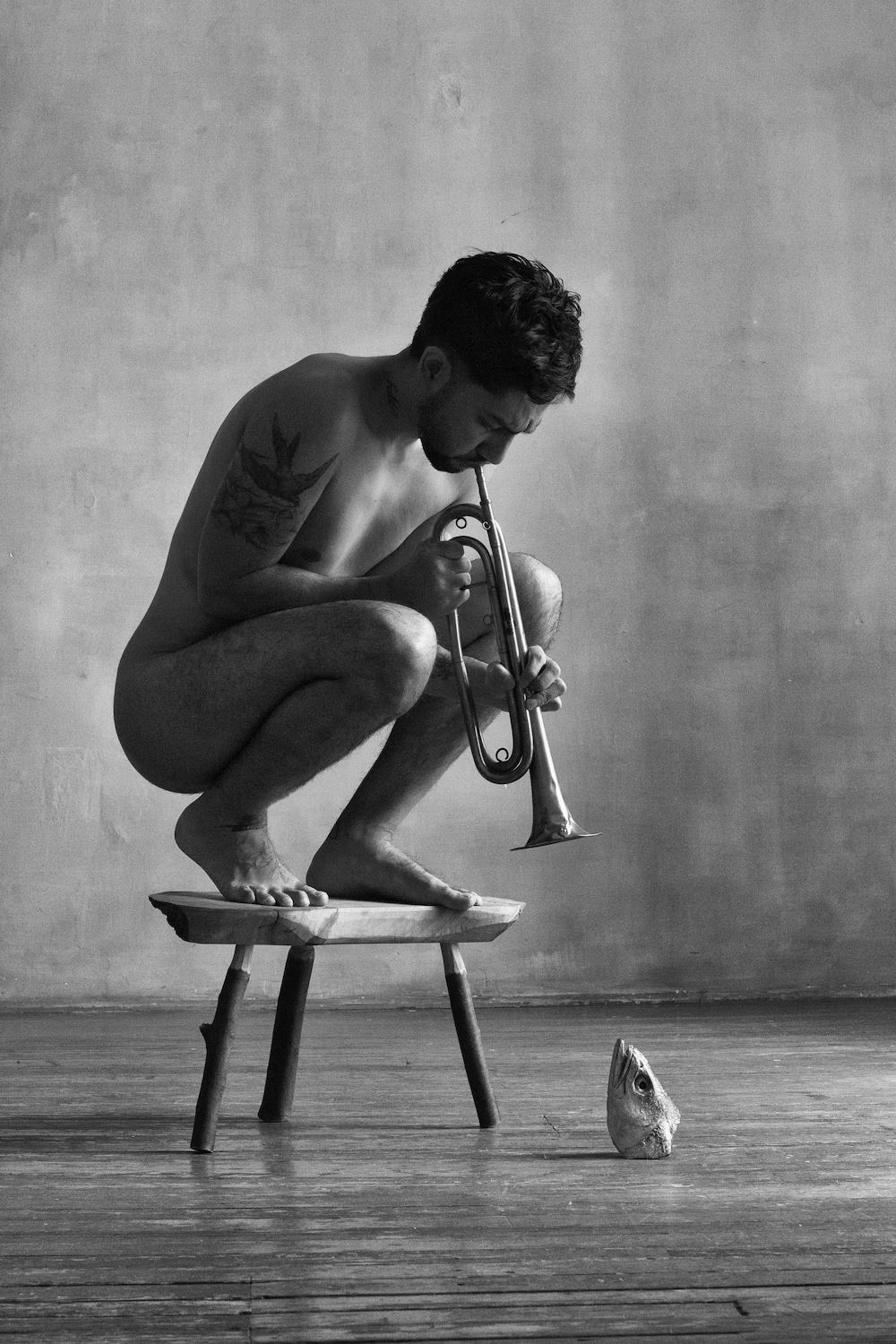

VC: Nudity and self-portraiture are essential elements of your visual language. What significance do they hold for you?

FT: Nudity entered my life at a very specific formative moment. My first nude session was with one of my closest friends, who was on a personal quest that he couldn’t transcend. During the session, a point was reached where an atmosphere of forgiveness, clarity, and a return to essence came to him, leaving a profound mark on me. The impact of nudity on personal growth, in conjunction with the creative process, can lead to a liberation or repositioning of objectivity in individuals.

From that point, I decided to embrace nudity under that commitment as part of my visual language and modus operandi. Over time, I have found deeper and more concise meanings in it, but broadly speaking, nudity, for me, is placing the human being as on their first day of creation, where their essence and the reality of nature are the only things clothing them. It means stripping away added entities to place them in their identity’s essence and, in parallel, in a genesis narrative: creating the beginning of new stories and universes from the deepest part of their being.

Nudity is placing ourselves in a simulation of birth, naked as in the womb, but at the same time in a simulation of death to the unnecessary, naked as at the moment of dying. In both cases, what remains is the essence, but what is expressed is the exposed corporeality.

VC: Beyond self-portraiture, how would you describe the importance of photography as the most direct way to understand, connect intimately, immortalize, and capture the essence of people?

FT: I’ve asked myself this question countless times. I still don’t believe I have a logical answer, but I do have a semi-coherent explanation. Without false pride, I consider that in many of my images, one can feel the person’s soul: their story, process, struggle, and victory. Each constructed project session has become, for me, the creation of a safe space to be. Every element within the session time aims at a reconnection with the person that allows my images to emerge from that state, honoring human worth and bestowing the gift of an exquisite image.

Perhaps I would add that the key to all this is that I decided long ago on two things. First, all the models are people I know: friends, family, colleagues, people whom I love and value, with whom we share a woven canvas of history. This opens up precious portals of vulnerability and grace. Second, I work with the ‘imperfection’ of bodies, the body in its present and real condition. There is great power in honoring the real, not in the frustration of the unreal. This allows, in conjunction with bonds of friendship, the soul to be free and come forward to pose to be photographed.

VC: Currently, you are developing a new project titled VÍA DOLOROSA, inspired by the loss of your grandmother. After her death, you decided not to learn about her after she was handed over for burial. How has this decision influenced your perception of death and grief, and how has this absence been reflected in your photographs?

FT: VÍA DOLOROSA came to me as the funeral ritual that I chose not to live. At first, I didn’t perceive it that way, but as the ideas solidified, I saw how the entire construction of them contained acts resembling a ritual, from the elements captured in the image to those not captured, such as the use of incense, music, soil from certain regions connected to the history with my grandmother, as well as the use of bodies or cycloramas.

The impact it has had on me has been and continues to be ambiguous, like the grieving process, I suppose, and ambiguous like the concepts of death that exist. In the end, what works is what brings us comfort and life in that moment. Absence is sometimes more scorching, sometimes lighter, but always creative. However, I believe that what it has given me the most is precisely this perception of continuing to explore and delve into the search for essence to manifest it in the temporality of the body or matter.

Pain, being one of the deepest emotions in human cavities, carries within itself the same capacity for release. Sometimes life hands us ashes, but the creative power always possesses the fury to turn them around and transform them into the most beautiful of conquests. Digging so deep to fly so high.

VC: I am captivated by the visual compositions you have achieved in the photographs of this project, especially the one bearing the title of the project itself. Could you share more about the inspiration behind this specific image and how it connects with the overall theme of your project?

FT: This piece is directly inspired by the week of the Virgin of Sorrows in Puebla and Oaxaca. From left to right, I decided to integrate: oranges placed on altars as a symbol of the corporality that holds the spiritual essence, the sweetness of life (fruit) surrounded by its bitterness (peel), pierced by rice paper flags symbolizing pain piercing or flagellating the body, purple flags representing passion or pain, and white flags representing temperance, purity, peace. The young man is from Oaxaca, covered with a hood simulating the silent procession in which hundreds of people dress as executioners and carry the Virgin through the streets of the city. In his personal context, each element represents me in confronting loss.

VC: And this one?

FT: This image narrates the denial of death, the reality of being, smelling (perceiving), knowing but not wanting to see, taste, or speak about the subject. Hence, the blindfolded eyes and the cut mouth, which create an imaginary sense of security that aims to bear fruit, evoking times of life and glory.

VC: How have the regions of Puebla and Oaxaca, the birthplaces of your grandmothers, influenced the narrative and aesthetics of VÍA DOLOROSA? Additionally, could you share more about the elements of the celebrations of the Virgin of Sorrows in these regions that have served as inspiration for this series?

FT: I believe that, by its syncretic nature, as Mexicans, we possess a strong religious-ritual identity instilled during the conquest era, which should be expressed through artistic endeavors. This imprint, with its myriad adaptations, remains very much present. Therefore, the construction of ceremonies, festivals, culture, and traditions is a rich sensory experience full of symbols, scents, flavors, and songs that shaped my imagination and influence many of the aesthetic constructions I create.

Regarding the narrative, all the expressions mentioned above always have a strong “why” or “for whom,” which is generally linked to ending up in a gathering at the grandmothers’ house. I suggest that this mode has somehow transferred to my creative universe structure.

I come from a patriarchal but also severely matriarchal country, where the cult of death is an intrinsic part. I feel that from this blending of essences, the celebration of the Virgin takes on a very potent force. The celebration varies depending on the region, but it essentially involves dedicating a week of worship to the Virgin of Sorrows, named so because it is believed that she is experiencing all the suffering leading up to the loss of Christ.

As part of the rituals, monumental altars are created where each element placed holds symbolism of comfort or a relation to death. There are days when condolences are offered to the figure of the Virgin. Other days, the entire city observes a vow of silence while a procession takes place, expressing empathy for the suffering of death. From all of this, countless points of visual inspiration have emerged: triangular figures, fruits, symbols, the poses of the models, lighting, etc.

What captures my attention is the ritualistic and ceremonial aspect, and the sensory experience lived within it. But I perceive that what intrigues me more is the act of questioning: Who consoles whom? Could it be that our worship is truly out of devotion? Or is it for self-consolation? Could it be that the Virgin is not the Virgin, but us? Is the ceremony a collective expression in the face of the suffering of death that we endure personally and collectively? At least in my process, I have believed more than once; believed that it is I who sustains the deity, not the deity sustaining me.

VC: How do you approach masculinity in a way that goes beyond traditional standards of male nudity in VIA DOLOROSA and throughout your body of work?

FT: During the production of nude art, I have found it challenging to discover artists who address masculinity beyond the standards of musculature, machismo, or Greek ideals. While some artists breaking these molds focus more on activism, queer nature, and inclusion, both are valid in their motivations and perspectives. However, in my exploration and practice of nudity, they do not entirely align with what I try to express. In my case, I consider starting the exploration from the intimate, meaning we begin with what internally breaks down the icon of masculinity, reconciles it with that, and projects it into an image that communicates the condition it is trying to maintain in a neutral stance between these two predominant aspects regarding male nudity. In other words, nudity in my work is a word to articulate, not the point to communicate. The fact that it is not yet a fully conquered point with enough naturalness, as on the female side, leads me to explore more on the topic. I am curious about what contribution it could make to our concepts and reformulations of reconciled masculinity, which implies vulnerability, fragility, and transparency.

VC: What role does bodily fragmentation play in the aesthetics and composition of this project?

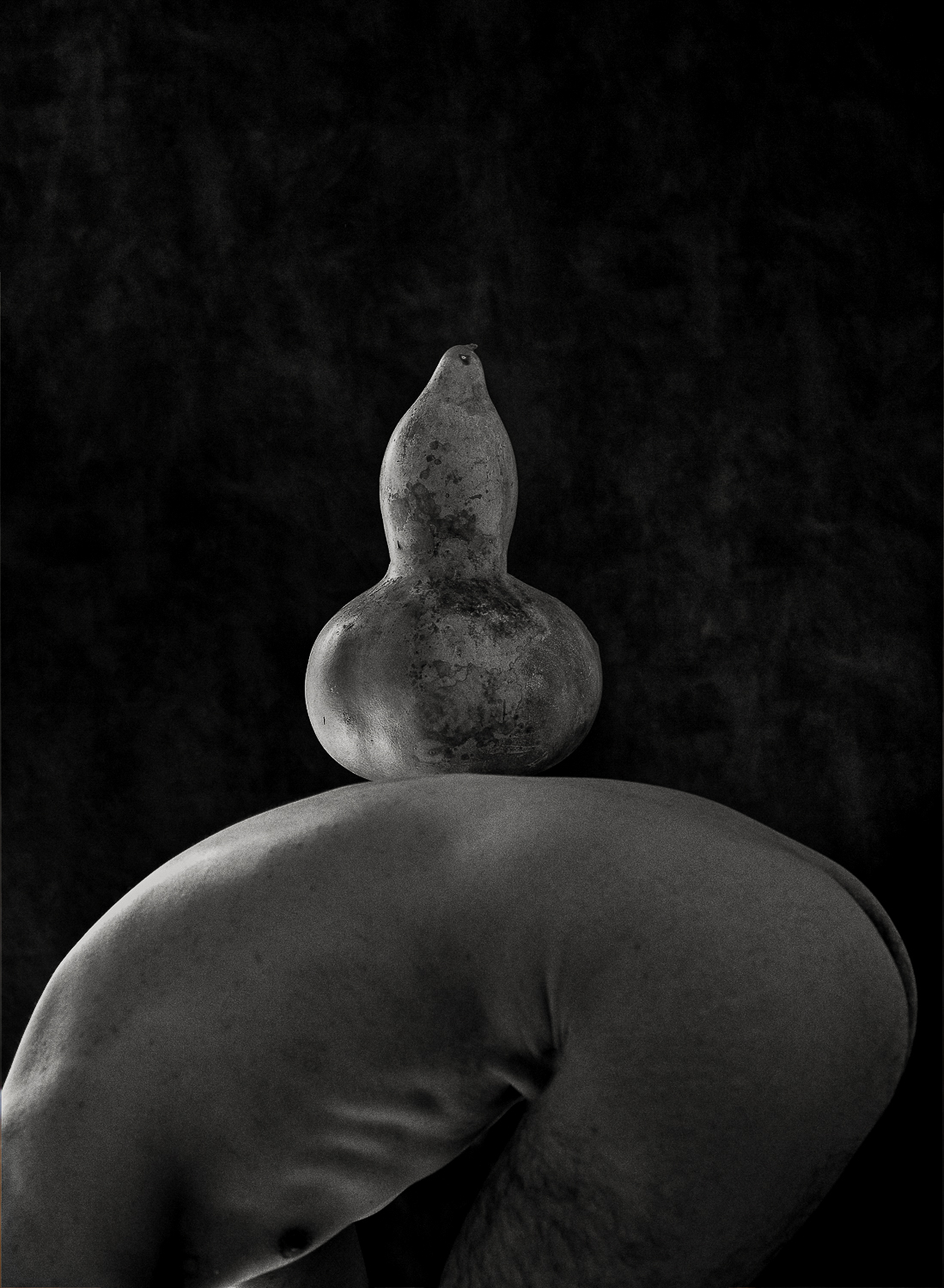

FT: It serves its purpose by expressing the corruptibility and glory of the body, narrating how it can hold an entire universe but, at the same time, can decay in a matter of time. It serves as a parallelism to the process of decomposition. There are two specific pieces that address the process of essence, conquest, and religious syncretism. In the first piece, Jicara, a native man holds the fruits of his own land on his back, symbolizing his strength, identity, and essence. In the second piece, Acanto, acanthus flowers are represented. Indigenous artists painted these flowers in monasteries and temples, using them for the worship of pre-Hispanic deities.

VC: Do you plan to continue working on VÍA DOLOROSA or explore similar projects in the future? How do you hope the audience will interpret and connect with your work?

FT: I eagerly anticipate the myriad interpretations it can generate, from the most vulgar to the most exquisite, and simultaneously, for those for whom it is the right moment to receive and discover it, I would love to create a path of comfort and liberation from pain for others as it has been for me.

Visually, I have continued with the theme, but I perceive it is veering somewhat to a side, somewhat isolated from the grieving process, and more directed towards visual and cultural elements. This coexists with the essence of the project but leaves me questioning whether to continue exploring in that direction or to maintain the initial block with its primary identity. However, I am working on the foundational pieces to integrate them or develop installations, audiovisual pieces, and possibly some performances.

Rooted Mexico, Mexico in tradition, are among my strongest and most enduring sources of creation. On that front, I believe that element will continue as a distinctive feature in my visual language, but I don’t know if I will continue with the theme of grief. I will probably explore funeral rituals, which are similar but not the same. We’ll see; I’m still in dialogue with myself about that.

Vicente Cayuela is a Chilean multimedia artist working primarily in research-based, staged photographic projects. Inspired by oral history, the aesthetics of picture riddle books, and political propaganda, his complex still lifes and tableaux arrangements seek to familiarize young audiences with his country’s history of political violence. His 2022 debut series “JUVENILIA” earned him an Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the Saint Botolph Club Foundation, a Lenscratch Student Prize, an Atlanta Celebrates Photography Equity Scholarship, and a photography jurying position at the 2023 Alliance for Young Artists & Writers’ Scholastic Art and Writing Awards in the Massachusetts region. His work has been exhibited most notably at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally in print and digital publications. A cultural worker, he has interviewed renowned artists and curators and directed several multimedia projects across various museum platforms and art publications. He is currently a content editor at Lenscratch Photography Daily and Lead Content Creator at the Griffin Museum of Photography. He holds a BA in Studio Art from Brandeis University, where he received a Deborah Josepha Cohen Memorial Award in Fine Arts and a Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography.

Follow Vicente Cayuela on Instagram: @vicente.cayuela.art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026