Austin Cullen: A Natural History (Built to be Seen)

This week we are looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our last call-for-entries–way back in late-2022 (a new call will be going out sometime in the near future, so stay tuned for details…). Today we are viewing and hearing more about A Natural History (Built to be Seen) by Austin Cullen.

Austin Cullen is a Houston based photographic artist and educator. He received his BFA from Stephen F. Austin State University in 2019, and his MFA from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 2022. He currently works as the Head of Digital Media at Cypress Falls High School, and as an educator at the Houston Center for Photography. His current project explores how museum displays and the natural world influence and affect one another. This project stems from his long-standing interest in natural history museums and the history of display. He has always been fascinated by the extravagant ways museums frame the American landscape. In his practice, Austin welcomes and encourages collaborative making and discussion. In the project, A Natural History (Built to be Seen) and dust watching, he has worked closely with several significant natural history museums, researchers, and exhibit fabrication companies such as the Field Museum, The Houston Museum of Natural Science, Morrill Hall: University of Nebraska State Museum, PBE Design Group, Kansas University Natural History Museum, and the Hastings Museum. Austin’s work has been included in numerous venues including Lawndale Art Center, Filter Photo Gallery, Candela Books + Gallery, and the Midwest Center for Photography. His work has been featured in Fraction Magazine, F-Stop Magazine, Urbanautica, Yogurt Magazine, and Sola Journal among other printed and online publications.

Follow Austin on Instagram: @austin_cullen

A Natural History (Built to be Seen)

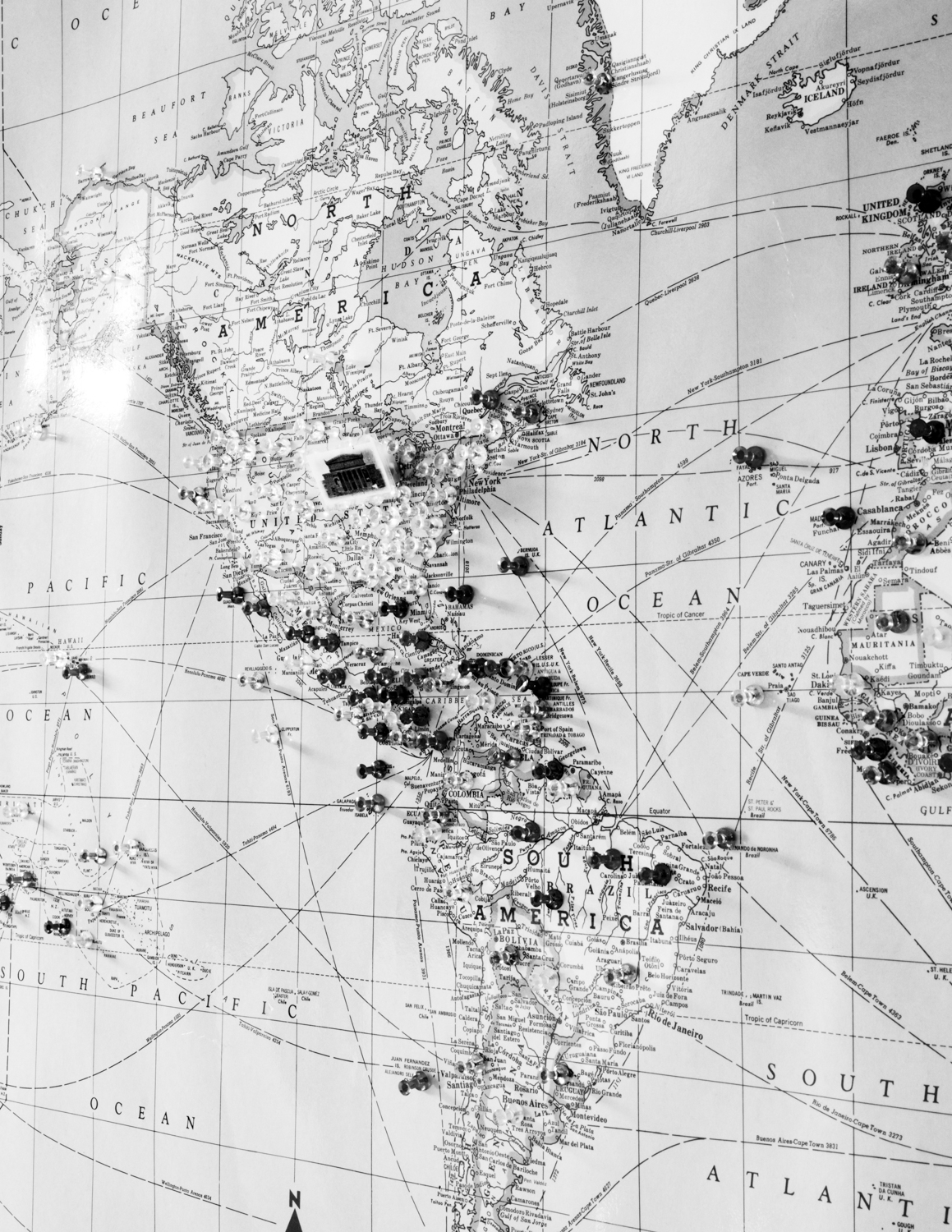

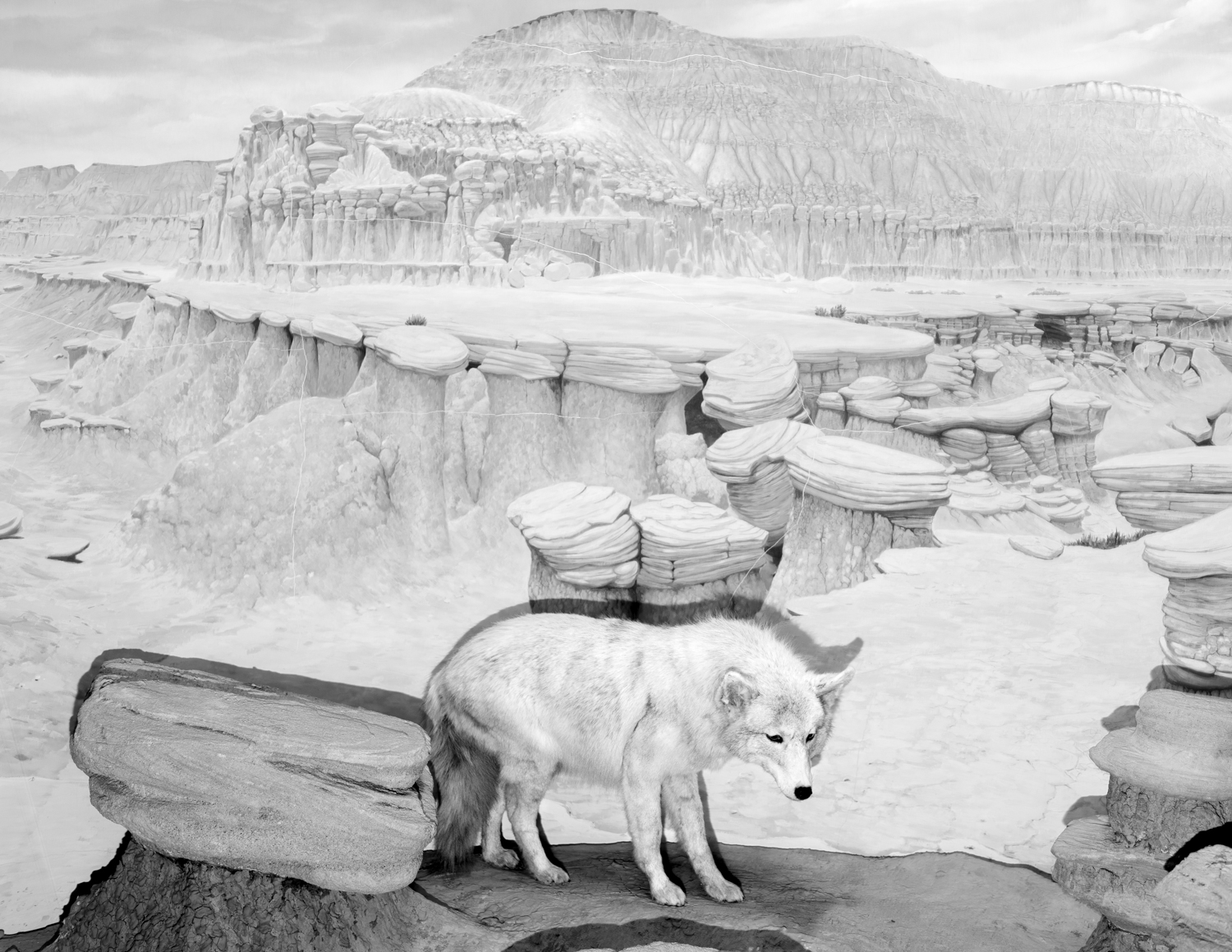

A Natural History (Built to be Seen) catalogs the various ways the western natural world is presented and reconstructed within museums. Documenting the life cycle of natural exhibitions, from inception to storage, both literally and metaphorically depicts how institutions shape nature. Dramatic dioramas, interactive virtual experiences, and miniaturized landscapes all act as windows into the natural world. While this framing acts as a guide for reading and understanding nature, the same frame can be analyzed to understand the complex and ever-changing relationship between people and land. Museums teach us about our environment, but often separate us from it. In an age of global climate crisis, it’s imperative to re-evaluate our understanding of and relationship with nature. By creating images that subvert the viewer’s ideas of what is natural or not, I’m asking the viewer to recognize how influential museum nature is on their understanding of the larger natural world.

Daniel George: What drew you to the museum and motivated the work that eventually became A Natural History (Built to be Seen)?

Austin Cullen: The motivation for my project stems from a childhood interest in museums, and an earlier body of work. When I was younger I regularly visited the Houston Museum of Natural History. The museum showed me a version of nature that was completely different from the city I grew up in. Instead of the urban bayou that I was used to, the museum depicted safaris, jungles, deep sea life, and so much more. In the museum, nature did not feel like something we as humans lived in, but instead a distant spectacle. It taught me about the larger world around me, and it left me awestruck by the far-off places and creatures the museum contained. Visiting the museum was a regular occurrence for me, and it heavily influenced my perspective on what I considered to be natural or not. It wouldn’t be until I was a student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln that I would begin to have a photographic interest in natural history museums. In an earlier iteration of the project, I was making images of a different interest of mine- the american western landscape and the myth of the west. With those photographs, I was deconstructing the myth of the american west while questioning my place within it. The images that resulted from this project blurred the line between reality and fantasy, and satirized and critiqued the western mythos. Museums were among the subjects that I photographed for the project, and eventually I began to focus on the museum subject exclusively. It was at this point that my childhood fascination with museums was reignited, but instead of approaching them as a passive viewer, I was instead looking at the museum with a more skeptical lens.

DG: In your biography, you mention working with natural history museums to complete this work. I’m curious how that partnership functioned, and the sort of importance they saw in participating in the creation of these photographs.

AC: Working with natural history museums has easily been my favorite part of this project. While I photograph, I’m often also having conversations with the scientist or fabricator that is showing me around. My interests, certain perspectives, and even specific photographs have been directly inspired by these dialogues. When first talking to museum professionals, I’ve found that most are hesitant about working with people outside the museum because of the fragility and importance of their collections. Once I’m in space however, people are often more than happy to discuss their practice, and the history of their collections. While the front-ends of museums are often well documented, the back-end and exhibition design process often goes un-documented, even though most of the important work happens in the time before and after the exhibition.It’s hard to say what exactly my collaborators think, but I believe that most I have met would agree with this sentiment.

DG: Could you talk more about your interest in depicting the various aspects of museum operations—from displays to store rooms?

AC: What I was initially drawn to when I started photographing in the back-side of the museum is the dramatic environment shift specimens can be found in. They go from being in environments that have minor or hidden human infrastructure within it, to it being overly abundant. When we visit a museum we’re only seeing the final product of an institution’s efforts. To emphasize the institutions’ hand in shaping the image of nature, it feels important to photograph the whole process. By documenting the varying states of specimens, I aim to demystify the final exhibition-ready product most visitors are accustomed to. I’ve also been very interested in seeing the decommissioned specimens and exhibition mounts that most research-institutions store. These mounts are often older, and as a result, vary greatly in form and philosophy. A bear from the early 20th century is going to look dramatically different than one that is taxidermied now. This is mostly attributed to advancements in the field, but more often than not the form of the posing and positioning of the bear itself is dramatically different. This shift in form coincides with the shifting values that museums attribute to nature. While it was once viewed as distant, extreme, and mythical, it has become something that is much more in-step with science and humanity. Photographing spaces that contain mounts from the 20th and 21st century really highlights the ever changing perspective we have of the natural world.

DG: What insights do you now possess into the ways in which “institutions shape nature?

AC: I’ve learned a lot regarding this question that it’s hard to narrow it down, but there are a few key insights that have stuck with me. The first being just how influential western museums had been in shaping the American landscape during the 19th century. The idea of the sublime landscape, a natural space or view that leaves the viewer awestruck by its physical and spiritual grandeur, was disseminated through museums and literature. This concept shifted how Americans thought about and treated the western landscape. For example, Yosemite National Park’s founding and protection can be attributed to 19th century photographers’ sublime-inspired images of the site’s landforms. These photographs then became the basis for how museums depicted western-themed landscapes. This connection between museums and the shaping of the larger natural world would continue throughout American history. Another thing that I learned in regards to the connection between museums and parks, is that often the designers for visitor centers are often the same companies that work within natural history museums. This of course makes sense because designing exhibitions requires a very specific skill set that requires a specialized company, but it is just another connection that I’ve observed.

Probably one of the most interesting things that I learned is not necessarily about how institutions shape nature, but more so about one of the consequences that museums face as a result of their past decisions in regards to mounting practices. As I mentioned earlier, dioramas were the go-to natural display for a very long time. Mounts (animals) that were displayed in dioramas were often posed in various exaggerated poses to make them feel more naturalistic. As a result of this decision, other taxidermists and private collectors would follow their lead and have their mounts treated the same. Best taxidermist practices and ideologies have changed significantly since then, but now there is an over-abundance of mounts posed in ways that make them take up significant amounts of space. In my experience, research institutions try to store as many specimens as possible, regardless if they were taxidermied for display or research. This is done to preserve mounts that are endangered or extinct, because they may prove valuable to research further in the future. Because of this, labs can end up feeling cramped because certain trophy mounts take up significantly more space than expected.

DG: And how would you say these photographs help us “re-evaluate our understanding of and relationship with nature?”

AC: When I was younger I learned about nature through museums. I had thought of nature as something that was distant. This was not some random conclusion that I had come to, but instead the result of a carefully constructed narrative the museums I loved had built. Just because museums are scientific, does not mean that they are objective or truly “natural”. Dioramas for a long time were the go-to for natural display. In a diorama, viewers are meant to stand outside of an illusionary space that is meant to represent a specific environment. For many museum visitors, dioramas are the only way they will ever visit specific spaces. That environment will forever be in their minds as something that is perfect and untouched by human hands. With my projects I aim to thoroughly break down this illusion by reveling in the flaws, process, and overall human elements that are present in our perspective of the natural world. Museums are always changing and adapting to better reflect new and emerging ideas about the world around us. They teach people how to see and read nature. What we ignore, respect, or strive for in nature can all be learned from the ways that we exhibit it. It’s important to recognize that power in an age of global climate crisis, and it’s imperative to understand both the positive and negative ways it influences the ways we interact with and shape the world.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026