Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca Roe

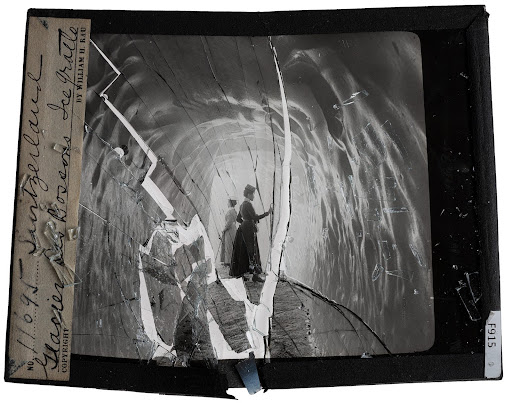

©Areca Roe, Laboratory, Corina researches seed banks, forest ecosystems, and how climate change affects plant life cycles and timing of seasonal events (Minnesota), 2019

In expanding our celebration of Earth Week, Earth Month: Photographers on Photographers will focus on the work of Eco.Echo Art Collective, a group of international artists deeply concerned with the well-being of our planet beyond human needs. The group’s concerns are climate change and anthropogenic activities’ global impact. Driven by an appreciation for the natural world’s beauty, diversity, and wonder, they believe in the inherent worth of all living beings regardless of their instrumental utility in fulfilling human desires. This week, members of Eco.Echo Art Collective will take time to reflect on each other’s work and how the transformative potential of photography can engage in challenging conversation and affect social change around ideas of humans and our surroundings.

Today, member Jason Lindsey will share his discussions with member Areca Roe.

Areca Roe is an American Artist based in the heart of Minnesota, Specializing in photography while embracing video, sculpture, and installation, Roe’s work is a testament to the intricate relationship between humanity and the natural world. As an Associate Professor at Minnesota State University, Mankato, she teaches and actively engages in this dialogue. Her Laboratory project showcases ecology researchers in personalized portraits that intertwine scientific dedication with artistic exploration. Through these collaborations, Roe illuminates the noble quest of understanding our living landscape, making the elusive realm of scientific research accessible and relatable.

Areca Roe’s Labratory statement:

This series of portraits is the result of artist residencies at Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve in Minnesota and Tallgrass Prairie Artist Residency in Kansas. At each location, I collaborated with ecology researchers to create portraits. I’m curious about their process, their questions, and what drives them to do their research. I also hope to elevate them as noble workers who are quietly and diligently working to tease apart and fathom the interconnected web of the living and non-living landscape, and put a human face on the unapproachable monolithic idea of scientific research. Each researcher chose a location (usually their own research plot or nearby) and a nature-mimicking fabric pattern to incorporate into the scene. The pattern stands in as a domestic element and speaks to our desire to connect to the natural world.

©Areca Roe, Laboratory, Grace researches historic bird population trends in Minnesota as a result of climate change (Minnesota), 2019

Below is a conversation between photographer Jason Lindsey and Areca that discusses her Labratory series.

Jason Lindsey: Inspiration Behind ‘Laboratory': How did you land on the evocative title “Laboratory” for this series? Was there a connection to the broader concept of humanity experimenting with our planet’s climate and ecosystems?

Areca Roe: I was thinking of the ecological space around the researchers as their laboratory, and was playing against the trope of the imagined scientist in a crisp white lab coat in a sterile lab. There are of course many kinds of scientists, but I feel like ecologists are a bit unsung, or less understood as far as what they study and do. I was also drawn to the double meaning—the Earth as lab subject that we humans are experimenting upon by drastically altering the land, water, air and climate.

©Areca Roe, Laboratory, Peter researches conservation of Topeka Shiner populations, an endangered fish species (Kansas), 2021

JL: Intersection of Art and Science: Do you see a symbiotic relationship between scientists and artists in terms of exploration and discovery? How has your background in science informed your artistic practice?

AR: I started out as a scientist, majoring in biology in undergrad and working in ecology and other scientific fields a bit, before going to graduate school for art. Art was always a huge part of my life, but I was very drawn to science as well, and have a drive to understand the natural world on a deeper level. Those interests carry over into my artwork, and I think the scientific training helps me interpret the world in a different way. Not all of my artwork is necessarily informed by science, but this series was definitely inspired by the work of ecologists. My background helps me understand their work, and to in some small way interpret it for a wider audience.

Both science and art are means of experimenting and gaining an understanding of the world, with differing end goals and levels of objectiveness/subjectiveness. I do think they are symbiotic, at least for my own practice!

JL: Choosing Researchers as Subjects: What drew you to portray researchers specifically? How does featuring them align with the project’s goals?

I’m curious about the researchers’ methods, their questions, and what drives them to do their work. I also just selfishly enjoy learning about science, hanging out with researchers, and making connections between the art and science realms. There’s much more we could do in this space connecting art and science!

A major goal of the project is to recognize the researchers as individual humans, and as important workers who are quietly and diligently teasing apart the interconnected web of the living and non-living landscape. It can be grueling work, long hours in inhospitable weather. The portraits are playful and a bit surreal, which I think highlights the subjects’ creativity and humanity.

I wish American society understood and respected scientists more. If we did, perhaps we wouldn’t be in such a climate mess now.

©Areca Roe, Laboratory, Nico researches bison and cattle impacts on grassland soil microbial and ecosystem properties (Kansas), 2021

JL: Significance of Location and Fabric: Why was it important for the subjects to select their portrait locations and the nature-inspired fabric patterns? Was there ever a moment when a chosen location didn’t resonate with you, prompting a change?

AR: I wanted the portraits to have a few elements of collaboration, and the researchers always know their plot or field and the surrounding areas like the back of their hand. The locations had meaning to the researchers, either in that their research was grounded in that space, or it represented something important to them. Sometimes simply beauty or peace.

I never felt like I couldn’t work with their location choices. It was a huge benefit to get an insider to take me to their spots! They had keys to gates and knew odd backroads, so it was exciting to ride along with them. One researcher, Nico, took me to a hilltop overlooking the seemingly endless Konza Prairie in Kansas, with several bison families dotting the valleys below. It was gorgeous. Others took me to their favorite bend in a creek they study, or favorite stand of trees. Researchers are also sometimes keen to share their love of a certain biome or ecosystem with the world. I could work with any location they chose, I just felt privileged to be along for the ride!

The nature-patterned fabrics are an element I use in much of my work, and to me it represents our attempts to connect with nature. I collect the fabric, so I’d usually show the researchers an array of fabrics via email beforehand, and they pinpoint one or two that resonate with them (I only used each pattern once for this project, having each subject choose a different pattern). I found it interesting what they were drawn too, and sometimes it resonated with the research, often not. I think it gave them some ownership of the imagery.

©Areca Roe, Laboratory, Craig researches how mycorrhizal fungi influence carbon and nutrient cycling and plant growth response to elevated CO2 (Minnesota), 2019

JL: Recurring Motif of Fabric: Fabric patterns have appeared in several of your projects. Could you elaborate on the specific significance of the fabric patterns in “Laboratory” and how this ties into your broader artistic exploration?

AR: It’s become a thread that goes through many of my projects, this human representation of nature in our domestic realms. I have always been intrigued by textiles, sewing, and fabrics. My mother is a talented seamstress, so I grew up sewing and I’m sure my affinity for fabrics originated there. To me, the botanical patterns I use represent our domestic and natural worlds overlapping. We attempt to connect with nature, but maybe in a way that’s not real, not symbiotic, not productive.

I began playing with botanically-patterned fabrics in my work many years ago. The floral fabrics I’m drawn to for artwork are a bit over the top, sometimes garish, or too busy. I like the way they visually push and pull with other colors, patterns and textures in nature. Obviously unreal, trying but failing to camouflage. To me the fabrics represent the domestic realm, as well as our desire to connect with nature. We love to surround ourselves with “fake” nature in our homes and buildings. Floral curtains, fake or real houseplants, wood textures. I do it too, of course. It’s tame and controlled, and sometimes it’s in lieu of protecting the actual natural world.

For Laboratory, I wanted to bring in this domestic element as a way to hint at that nature-human connection we aspire to, and as a visual cue that this is a heightened portrait, not reality. I also wanted to differentiate it from straight photojournalism, and have it be a little bit more surreal or heightened, more obviously a concoction.

JL: Evolution of the Project Idea: Did the inception of “Laboratory” stem from a moment of inspiration during another project? How do your projects inform and evolve from one another?

AR: There are often seeds from other projects, definitely! Part of this inspiration came from working with scientists in Alaska to locate areas of drunken forests (trees collapsing or leaning over due to rapid permafrost thaw and climate change). I had the opportunity to photograph on a bog research site near Fairbanks. It was a rich experience, and I realized I missed hanging out with ecologists! So, somewhat selfishly, I thought it would be fascinating to learn more about each researchers’ work, and hang out in beautiful locations. But I also thought others would get something out of learning about these researchers too, and putting a face to “science.”

JL: Experience and Insights from Artist Residencies: Completing this project across two artist residencies must have been a unique journey. Could you share how these experiences shaped the project and perhaps offered unexpected insights or challenges? how did this experience seed or nurture the development of “Laboratory”?

AR: I’m a big fan of artist residencies, as a way to connect with others, in this case scientists, and to get out of your ruts and comfort zones. I find them to be incredibly productive.

The first residency, at Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve in Minnesota, was very pivotal to me. During college I worked and lived there for a time, assisting with ecological research—it’s where I learned a lot of botany and how to identify prairie plants and grasses. Many years later, as an artist, I heard they had started an artist in residence program. It allowed the artists to work with scientists or the landscape there, and I jumped at the opportunity. I felt very lucky to connect with many scientists through this residency, and spend a lot of time at the research station. It was so enriching, I think I started 4 different projects while I was there! Laboratory wouldn’t have happened without the support of the folks at the residency, so I’m grateful for their vision of artistic and scientific collaboration.

The Tallgrass Residency in Kansas was also fantastic, and allowed me to connect with many more researchers for Laboratory. The residency was 10 days, which was perfect for me as I can’t be away from my kids for very long periods. (Residencies can be very exclusionary to parenting or care-giving artists– many I can’t even consider applying to.) I fell in love with the flint hills area of Kansas; it’s stunning and vast, and I’ve never seen so much healthy prairie.

For each residency, the place itself steered the project, as I’m trying to be responsive to the landscape as well as the subjects in these photographs. And the researchers are certainly responsive to their landscape of study. We work with the wind, the rain, the cold or heat, and try to follow the beauty in each situation.

©Areca Roe, Laboratory, Kally researches prairie and oak savanna ecosystems, and how they are affected by elevated carbon dioxide (Minnesota), 2019

JL: Personal Influences: Has personal anxiety or concern about climate change spurred the conception of this project? How does the reality of climate change, especially considering your children’s future, shape your work?

AR: Anxiety or concern about climate change is always in the back of my mind. It’s already manifesting. This was a truly bizarre warm and dry winter in Minnesota, for instance. I have two kids, and I feel intense anxiety for their futures. Will there be disruption to agriculture, mass migration, war? I just don’t feel like we are on a positive trajectory, but I still need hope and optimism. Collaborating with these scientists helps me remember there are talented, thoughtful, caring people researching climate change as well as all other aspects of ecology, like soil health, bird migrations, and so much more. So yes, in a way working with scientists was a way of addressing the climate anxiety!

Many of the researchers are in their early career, as post-docs, graduate students, or even undergrads. Partly because that’s who is doing much of the boots-on-the-ground field research and who has time to be in the field with me. I find their choice to go into ecology and research an optimistic one. They must know they can make a difference, they can contribute to our knowledge with their work. They can perhaps find out how climate change will affect their subject, as that is increasingly necessary in all ecology research. Knowing them is comforting and optimistic, on some level.

JL: Artistic and Environmental Responsibility: How do you see your role as an artist in the context of environmental activism or education? Do you believe art has the power to influence public opinion on climate change?

AR: I think creative works, including work like documentaries, fiction, movies, not just capital “A” art on a gallery wall, can shift public opinion and thus policy. Realistically, huge scale policy change is what’s needed to fight climate change. I think art is one piece of the puzzle, with of course scientific knowledge being a huge piece. Creative work can tap into emotions, make connections between abstract ideas. It feels hubristic to say my work changes minds, and I don’t feel called to make nakedly persuasive artwork–I don’t know how well that functions anyway. But I might not create if I thought it made no impact, and I do create in order to connect with others. I hope to evoke feelings and spark ideas and conversations.

For this project, Laboratory, I do hope to humanize the scientists, to show they are hardworking, thoughtful, creative real humans, and to foster more trust and respect.

©Areca Roe, Laboratory, Mary researches how climate change alters resources for plants in grassland communities (Kansas), 2021

Areca Roe is an artist based in Mankato and Minneapolis, Minnesota. She works in many media; primarily photography as well as video, sculpture, and installation. A recurrent theme in her work is the interface between the natural and human domains. She is an Associate Professor of photography and video in the Department of Art and Design at Minnesota State University, Mankato.

Roe received her MFA in Studio Arts, with an emphasis on photography, from University of Minnesota in 2011.

She’s a member of Rosalux Gallery, an artist collective in Minneapolis. Roe has also received several grants and fellowships supporting her work, including the Minnesota State Arts Board Artist Initiative Grant and the Art(ists) on the Verge Fellowship. Her work appears on several websites, including Colossal, Slate, Juxtapoz, WIRED, National Geographic, and Fast Company; and in print magazines, Der Spiegel Wissen magazine and Le Monde. Her work recently became part of the permanent collection at the Minnesota Museum of American Art and the Minnesota Historical Society.

For more about Roe and her work, visit arecaroe.com and follow her on Instagram @arecaroe.

Jason Lindsey is a Midwest-based photographer and filmmaker working to interpret science and the human impacts and relationship to the natural world. Lindsey considers himself a poetic activist using his art to drive social change.

Lindsey received his BA in Fine Art from Illinois State University. Lindsey has a 20-year career in advertising and editorial photography with a continued focus on Fine Art Photography. Photo assignments have taken him from the jungles of the Amazon, the Glaciers of Iceland, the Wilds of Alaska, and the waters of Belize. Lindsey is currently the Artist in Residence at Prairie Rivers Network and has photographs in a United Nations Climate Change and The Climate Museum exhibit in New York City and another United Nations exhibit in Paris.

He has been featured in PDN, Communication Arts, and Archive Magazine and was named one of the top 200 Advertising Photographers Worldwide in 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021. Lindsey’s book “Windy City Wild: Chicago’s Natural Wonders” was published by Chicago Review Press.

Ask Jason about his 100% Solar and geothermal-powered studio if you are into that.

For more about Lindsey and his work, visit JasonLindsey.art and follow him on Instagram @jasonlindseyphoto.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Gadisse Lee: Self-PortraitsDecember 16th, 2025

-

Scott Offen: GraceDecember 12th, 2025

-

Izabella Demavlys: Without A Face | Richards Family PrizeDecember 11th, 2025

-

2025 What I’m Thankful For Exhibition: Part 2November 27th, 2025