A Drying Heartland: The Arid Photographs of Nicolás Marticorena

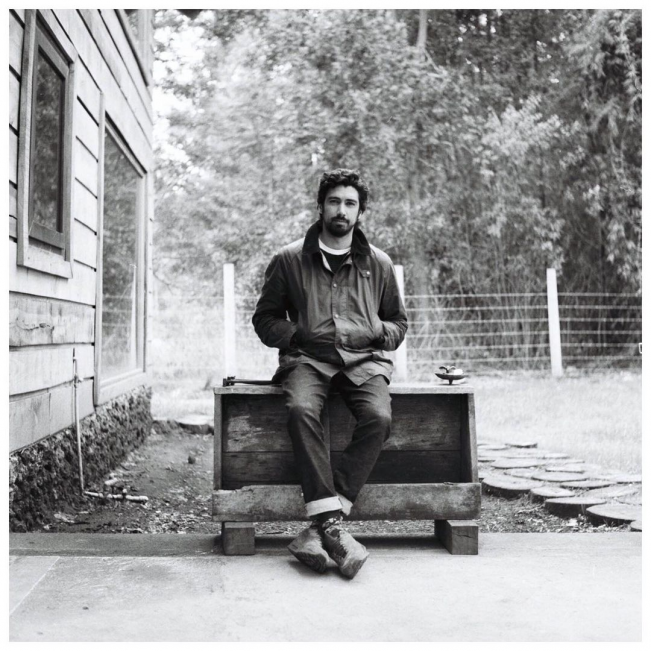

This week is dedicated to Chilean photographers working across a variety of genres. Today our focus is on Nicolás Marticorena, a journalist, sociologist and photographer whose global practice explores issues of climate change, drought and its effects on the human condition.

My body leaves you drop by drop.

…

I evaporate like moistness from your body.

…

Everything’s gone! Everything’s gone!

— Gabriela Mistral, Ausencia, from Tala, 1938

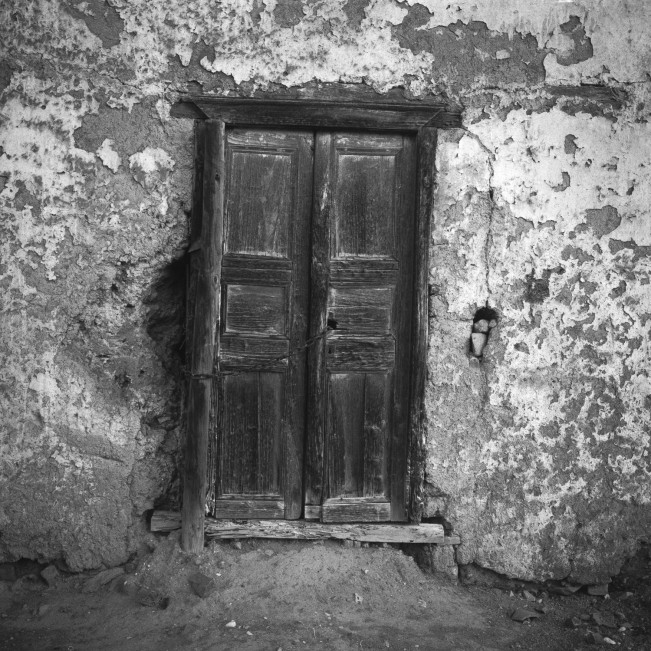

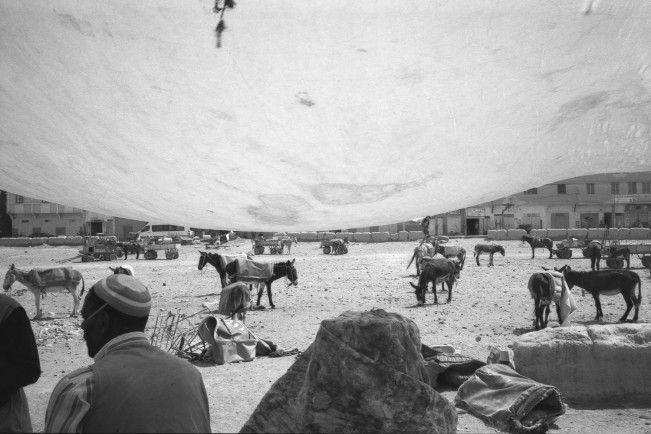

For over six years, Chilean analog photographer, Nicolás Marticorena has been documenting the drought-stricken province of Petorca and the slowly fading agricultural towns dotting the mountainous Region of Valparaíso. Located just a hundred kilometers off the country’s capital, Petorca has become one of the most infamous and damaged territories by the Chilean mega drought, which has been causing havoc in the region since the early 2010s.

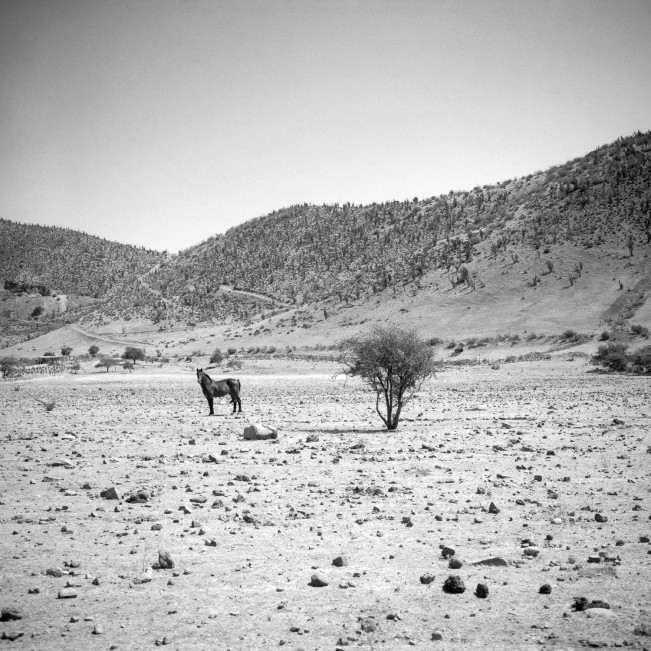

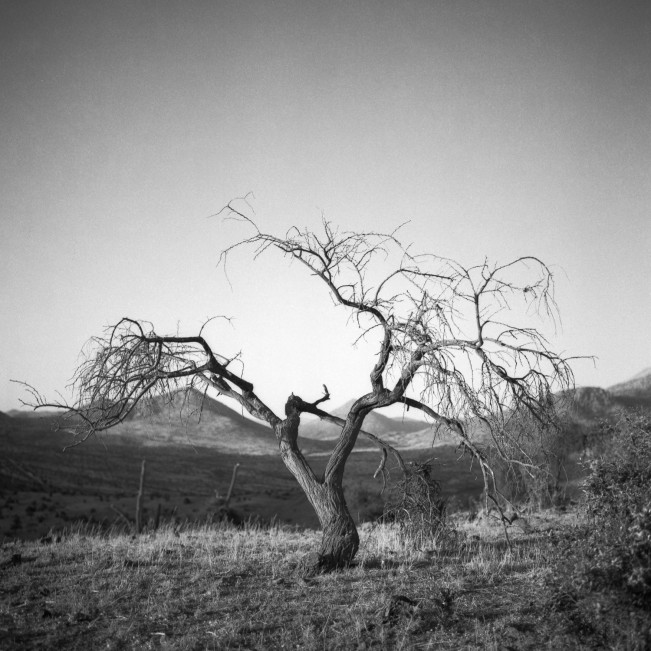

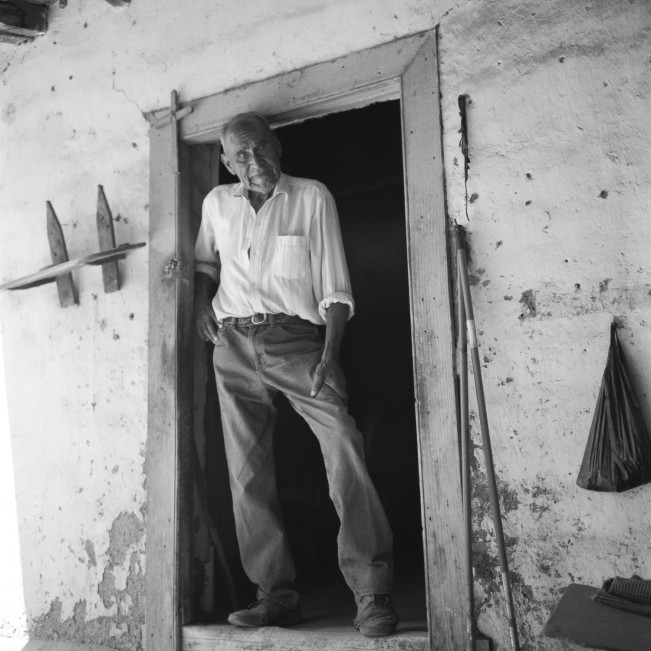

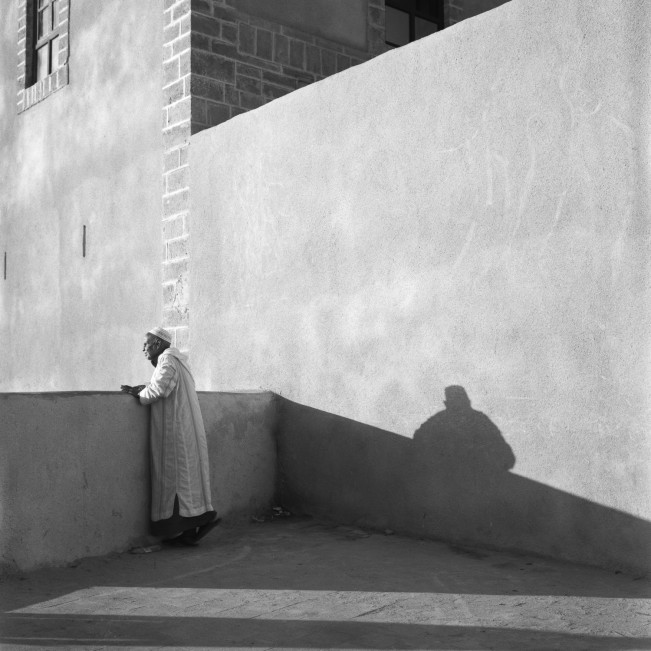

Reflecting on the desolate landscape of his own emotional journey, Marticorena’s photographs, however, reveal not only the devastating effects of climate change and our inadequate responses to it. They also capture its metaphysical and emotional dimensions, honoring the humanity and indomitable resilience of the rural communities most severely impacted by it. The images are powerfully emotive, revealing an astute photographer sincerely documenting the unbreakable bond between the land and its inhabitants as their sustenance, memories and traditions are increasingly threatened by the salty breath of the encroaching desert.

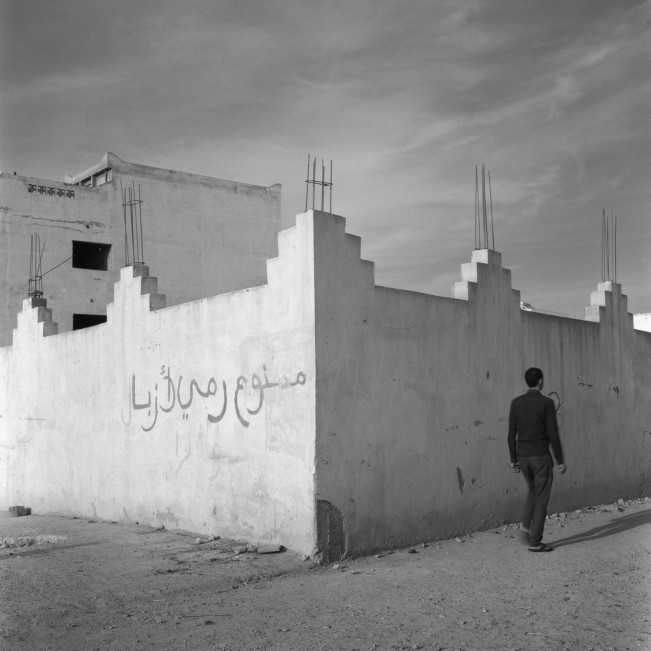

Desolate and expansive like the thousands of kilometers of barren lands traveled, his ongoing project Aridez (Aridity), presents a global approach to this issue, chronicling the devastating consequences of water scarcity during his solo travels in his homeland, Mexico and Marruecos.

Nicolás Marticorena (Santiago de Chile, 1983). He studied journalism and photography at Andres Bello University and has a PhD in Sociology from the University of Barcelona, Spain. As a journalist and sociologist, his approach to analog photography began during college with an initial interest in documentary photography. Over the years, he has been exploring other styles and developing a personal photographic look, which he conducts as a process of internal search and expression that allows him to connect with the contemplation of the environment, people, and the intimate. Since 2021, he has deepened his photography knowledge and capabilities through workshops with renowned photographers Luis Poirot and Fernanda Larraín, with whom he has been learning laboratory techniques for more than two years. In 2023, he was part of Pasajero, a group exhibition of analog photography at Centro Cultural Las Condes.

Follow Nicolás Marticorena on Instagram: @nicolas_marticorena

Vicente Isaías: How long have you been taking photos, and how long specifically in Petorca?

Nicolás Marticorena: I started with photography in 2005 studying photojournalism. Then I became very self-taught. However, my approach towards more authorial work was through the development of this project about Petorca, four years ago. The mega-drought in Petorca was a theme that worried and impacted me a lot. At that time, drought and water crisis were already stressing many places. I started in 2019. During the pandemic, I moved to the 5th Region of Valparaíso and took advantage of that to try to go to the area once or twice a month. I traveled (and still do) mainly on weekends, by car, alone, to explore and try to get to know all the towns there, to talk to people, to know the surroundings, to go down roads. (smiles) I think I’ve traveled all the unpaved roadways, mining roads, and that has led me to discover a lot.

VI: To provide some context, Chileans have been experiencing a mega-drought for over a decade. In rural areas like Petorca, the effects of climate change such as desertification and socio-environmental issues have been exacerbated by the precarious regulation of agribusiness and the over-exploitation of “water rights.” Additionally, during the pandemic, it was revealed that the amount of water these communities received from water tank trucks was very low, less than half of the amount recommended by the WHO, in fact.

NM: It’s a mix of factors. If you delve into this, there’s a large part of Chilean territory subjected to this. During the pandemic, there were news stories that impacted me greatly about situations I needed to witness. For example, when they began to restrict water supply in schools, people couldn’t even receive education because there was no water. In Chile, we’re approaching half a million people who only have water supply through tanker trucks. Climate change is generating water scarcity in a context where there’s no proper management of water resources, where there’s no planning, where many resources are also private, there’s no prioritization, no organization, and with that, obviously, complications are exacerbated and problems that we currently know start to emerge.

I think it’s a very difficult reality. Many people from the area, especially the older ones, told me that they had already experienced droughts, but nothing like this. There’s an uncertainty where a lot of nostalgia also coexists because the landscape has transformed. Forests have disappeared. The geography is being laid bare through the withdrawal of vegetation and the advance towards arid and desert-like conditions. There’s a metaphysical dimension to all of this, seeing how life is dying or transforming or clinging on in that process.

VI: So your interest in the province of Petorca arises in some way from this conflict.

NM: Completely, it caught my attention from a more macro-social perspective — how a phenomenon related to ecology and the environment can also strain our relationships as human beings, as social actors in a particular space. At first, I had… an approach to that conflict from the media, from the framing that the media put on this. It caught my attention a lot. I wanted to know what it meant for there to be no water in an area, or why there are suicides among farmers; or what other social problems will begin to manifest as a result of this water crisis.

That has been mainly the process of how I started to approach this project. I needed to go and connect — to understand the place, understand its geography, understand the communities that were there, get an idea from a much more present perspective of something that I only saw through the media.

Petorca is not limited to just being a town; it’s a province with diversity. Located between the mountains and the Pacific Ocean, it’s crossed by approximately three major rivers, whose waters are no longer superficially appreciated. My initial focus was to understand this context. Going there brought me closer to understanding that developing an authorial perspective has had two very important themes for me, two paths that have been key.

VI: What are they?

NM: The first one has been how I’m going to approach photography. I’m not from Petorca. Petorca is only 150 km from Santiago. I started going there once or twice a month, especially in the first year, with my camera and to explore. The authorial aspect emerged because inevitably when you go in a certain way on a trip that is not tourism, but instead a meaningful journey to encounter something, there is an opportunity to find things, to be amazed. I don’t have a scheme to say “I need this photo,” but rather I seek it, and if I find it, I feel grateful for finding it. In a way, I’ve said, “well, all the circumstances led me to this, whether to be fascinated by the people, to converse, and to be somewhat unchained and free from the pressure of taking a photograph.”

VI: And secondly?

NM: Secondly, the analog method implies a deep connection with the materials and a slower process. Calmly analyzing the negatives revealed the direction of my gaze and made me realize that what I’m developing is more of an authorial work than documentary. I would like the project to convey sensations. Hopefully, it’s an achieved objective, that the photographs that ultimately remain in the project generate a connection with someone and some kind of emotion.

For me, a good photograph has to have a degree of abstraction. It also has to have a degree of suggestion, and it has to evoke some kind of emotion. And in a way, it must succeed in communicating the sensitivity of the person who captured the image. That’s why in this process I’ve been moving away from photojournalism and have wanted to delve much more into what is the authorial gaze.

VI: The photos are very evocative. They captivated me from the moment I saw them in one of your exhibitions. What cameras do you work with?

NM: The majority of the photos are taken with a Rolleiflex. I really like it because it opens many doors with people, unlike other cameras that are more invasive. People see it and open up much more, they become less nervous and open many more doors for me.

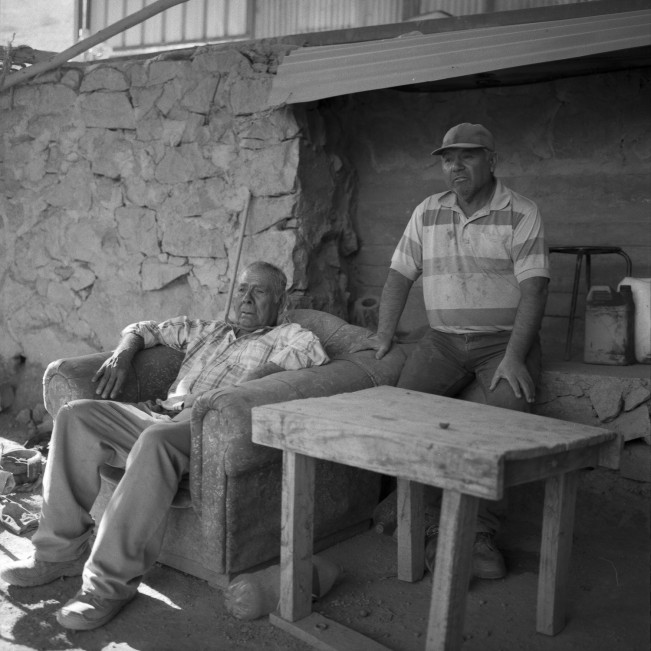

VI: Let’s talk about the people then. How has your interaction been with the inhabitants of Petorca?

NM: I got to know many families. People are very open, there is a lot of humanity in the sense that, unlike other places, when you go with a camera, they open their doors to you. There’s no barrier, no distrust. On the contrary, many times I even preferred not to take photographs to deepen conversations with people. This openness is not only seen among people; the animals themselves also approach you, as if there is a desire for connection between life, seeking life, and connecting.

VI: You must have many very interesting anecdotes with these people, what a privilege to get to know their stories up close. Can you share one with us?

NM: I remember some people who invited me to take photos of their farm. They had avocado crops, but unlike what one might think here in Santiago — that they are assumed to be large companies — these people were small farmers who had a few avocado trees and lived off that. I spent a Sunday with them and began to understand that they saw water as a complication because they had to make very tough decisions. For example, they couldn’t have more than one or two dogs because that would imply giving them more water, or they had to decide day by day whether to water the plants or not. All those decisions really impact you.

Petorca caught my attention demographically. It’s an area that is also emptying out, not just of water. The vast majority of the population are elderly and you only see very young children. Someone your age or mine has already left. The people who remain are individuals who generally have testimonies that are key to forming a perspective on what’s happening, or on the place, or on the people. Beyond the issues, they allow you to understand the context, the province itself.

VI: Which is very important because we must not forget that these places have life. The people who live there know the history, and with this phenomenon that is increasing more and more—migration due to climate change and age displacement—a huge historical and cultural heritage is lost.

NM: Absolutely, and that caught my attention a lot. There are many elderly people who, unlike in the city, are still completely active. I mean, there in Petorca, the productive activities at the core of the province demand it; it’s an area that traditionally was mining, small-scale mining. There are many people who worked in the hills extracting gold, who have countless stories and traditions. It’s interesting because the avocado issue is a relatively recent phenomenon and one sees it more because it’s the most media-covered, but there’s a series of other crops and activities that have been carried out in the area for a long time. That’s why I emphasize again that this is a multifaceted phenomenon. One can no longer blame just one issue regarding the water crisis, just as you can’t understand the history of the place without encompassing the complexity of the area.

VI: Of course, it’s something much more expansive. Speaking of expansion, the central theme of your work is aridity, and in this project, you’ve also linked it to a series of travels, bringing this theme to a more global perspective. Where does that idea come from?

NM: When I visited Petorca and other places with vast empty spaces, I began to appreciate new things, to discover and connect with personal aspects. I transferred this experience to other places that had no geographical relation, but that I felt equally close to. I started to see certain relationships of people with the environment, perhaps certain similarities that began to catch my attention, and above all, certain things that were happening to me and that I have been discovering over time. I realized that I had already made several trips that showed this.

I have always enjoyed traveling, and I realized that my recent trips were somehow connecting with my photographic work. I started visiting arid places that were related to my project. Some of the photos are from Morocco and Mexico. This approach has evolved, and I believe it’s the path I’m currently developing. I would like to expand it to other areas in Chile and also to other parts of the world, as many regions are experiencing water stress.

Through the images, I delve into the thread of aridity as an environment that allows me to connect with resilience. From the flora that clings to underground water sources to communities that remain in those places as a family legacy or for spiritual reasons.

If you think about aridity and the places in the world where water stress exists, one-third of the planet’s inhabitants are in that situation. Morocco, which is tremendously affected by water scarcity, is part of an area that has had a historical relationship with aridity, which is even expressed at a literary level, as well as poetically, completely.

In my travels outside of Petorca, I begin to introduce photos from other trips. I also change proportions because I change cameras and culture, using a 35-millimeter format that I mix with the other photos from different places.

VI: I’m intrigued by what you said about aridity and personal situations, perhaps to conclude you could tell us more about the relationship you see between the two.

NM: I believe that aridity can also reflect a lot on spiritual aridity or other types of aridity that we have experienced as individuals and that we have found some way to cope with or overcome, or simply understand.

I’ve been very intrigued by the work of Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide, and I’ve read a lot of her books and interviews. I connect a lot with her way of photographing. She says that when you take a photo, you are interpreting reality, and what lies behind that is all the feeling and knowledge that has made us who we are as individuals. And I think that when I connect with this, with this place, with this theme, undoubtedly it is seen and connects with who I have been, what has made me a person, and with my life experiences.

Perhaps my aridity in life has been the traumatic death of my father and also heartbreak, in the sense of how to learn to relate to love in the future. I believe that all these things that shape us as human beings and give us our psychological tools, in a way, allow us to overcome aridity, discover it, digest it, or perhaps simply understand it.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anastasia Tsayder: ARCADIAJanuary 28th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Kevin Cooley: In The Gardens of EatonJanuary 8th, 2026

-

William Karl Valentine: The Eaton FireJanuary 7th, 2026