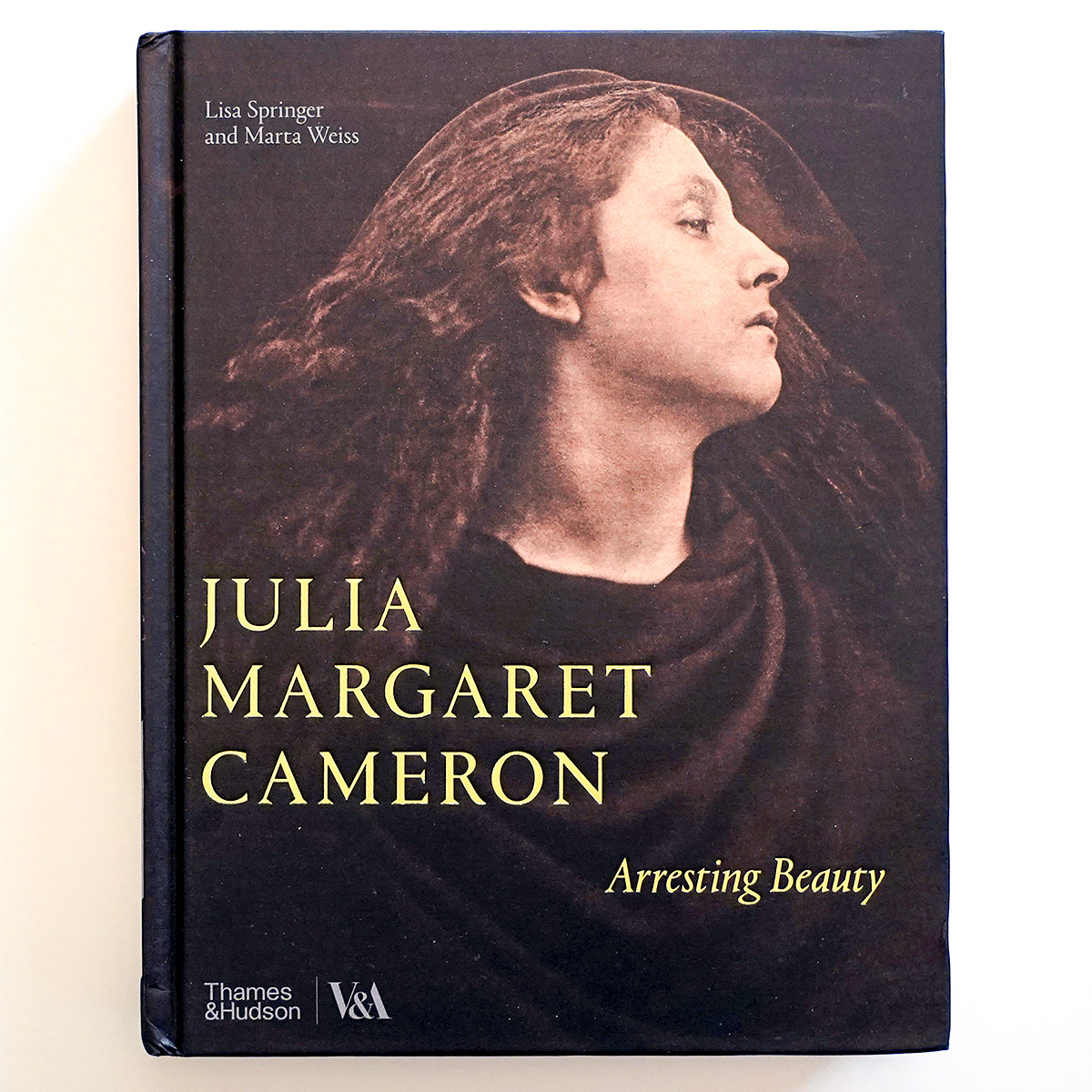

Arresting Beauty: Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron, Call, I Follow, I Follow, Let Me Die!, 1867, carbon print © The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A, acquired with the generous assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Art Fund. Museum no.RPS.735-2017

Julia Margaret Cameron (English, b. India, 1815–1879) received her first camera at the age of 48. Her portraits depict family and friends; contemporary scientists, scholars, and artists; and scenes staging allegorical, biblical, historical, and literary stories. For over a decade, she produced thousands of photographs and built a career, selling and exhibiting her work internationally—making her career even more impressive for its brevity. Her distinct style sets her apart, and her legacy positions her as an artist who broke ground for future photographers.

Highlighting this renowned photographer’s pioneering style, Arresting Beauty: Julia Margaret Cameron is a major exhibition currently on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum through July 28th, 2024. I asked Kristen Gaylord, Herzfeld Curator of Photography and Media Arts, to elaborate on the importance of Cameron’s work.

A book review of Arresting Beauty by Melanie Chapman can be found here.

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Rosebud Garden of Girls, 1868, albumen print © The Royal Photographic Society Collection atthe V&A, acquired with the generous assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Art Fund. Museum no. RPS.1129-2017

LL: What made Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographic portraits and narrative tableaux so extraordinary in the 1860s and ’70s and what makes them so important to the history of photography today?

KG: One of the most exciting aspects of this exhibition (for photo nerds, anyway) is the inclusion of three of the original pages of Cameron’s unfinished text, Annals of My Glass House (scans and audio are available on the V&A website). Called “part memoir, part manifesto” by V&A curator Marta Weiss, it’s where Cameron herself outlines how she differed from contemporaneous photographers. She writes that she wanted to claim photography as a fine art, beginning an effort that would culminate with the Pictorialists decades later. To do so, Cameron sought to elevate her subjects out of the everyday, mundane world into a realm of intellect, ideals, history, and religion. Her emphasis was not on capturing the most accurate and detailed likeness, but in revealing “the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer.” In Annals she scathingly dismisses a photograph that, a decade previously, had beat hers out for a prize, arguing that the result “clearly proved to me that detail of table-cover, chair, and crinoline skirt were essential to the judges of the art, which was then in its infancy.”

As this anecdote and many excerpts from reviews of the time attest, her single-minded vision of photography had its detractors, and she received no shortage of criticism, much of it sexist. But Cameron’s photographs were also admired by contemporaries and purchased by a museum that would become the V&A. The first monograph about her, authored by painter and critic Roger Fry and writer Virginia Woolf, Cameron’s niece, came out in 1926. In a world still struggling to make up for the scores of artists it has overlooked, Cameron is the rare example of a woman who never really left.

“My aspirations are to ennoble Photography and secure for it the character and uses of High Art by combining the real and Ideal and sacrificing nothing of the truth by all possible devotion to poetry and beauty.”

Julia Margaret Cameron, La Madonna Aspettante (Yet a little while), 1865, albumen print. Purchased from Julia Margaret Cameron, 17 June 1865 V&A: Museum no. 44747

LL: After raising six children, fostering five more and managing her estate on the Isle of Wight, it is clear that Cameron fulfilled Victorian expectations of womanhood as the manager of a successful household. Can you speak to how she came to transcend these expectations by demonstrating her authority and agency as an artist? Did she transcend domesticity in her work, or perhaps bend it to her will?

KG: Like many energetic, educated, ambitious women throughout history, Cameron carved out a full life, even with the limitations of what was allowed and acceptable. As what we might call today a “people person,” she seems to have thrived with a full household, a busy social calendar, and wide correspondence with artists, scientists, and writers. This sociability is inextricable from Cameron’s artistic career; in thousands of photographs, she never made a single one without a person in it!

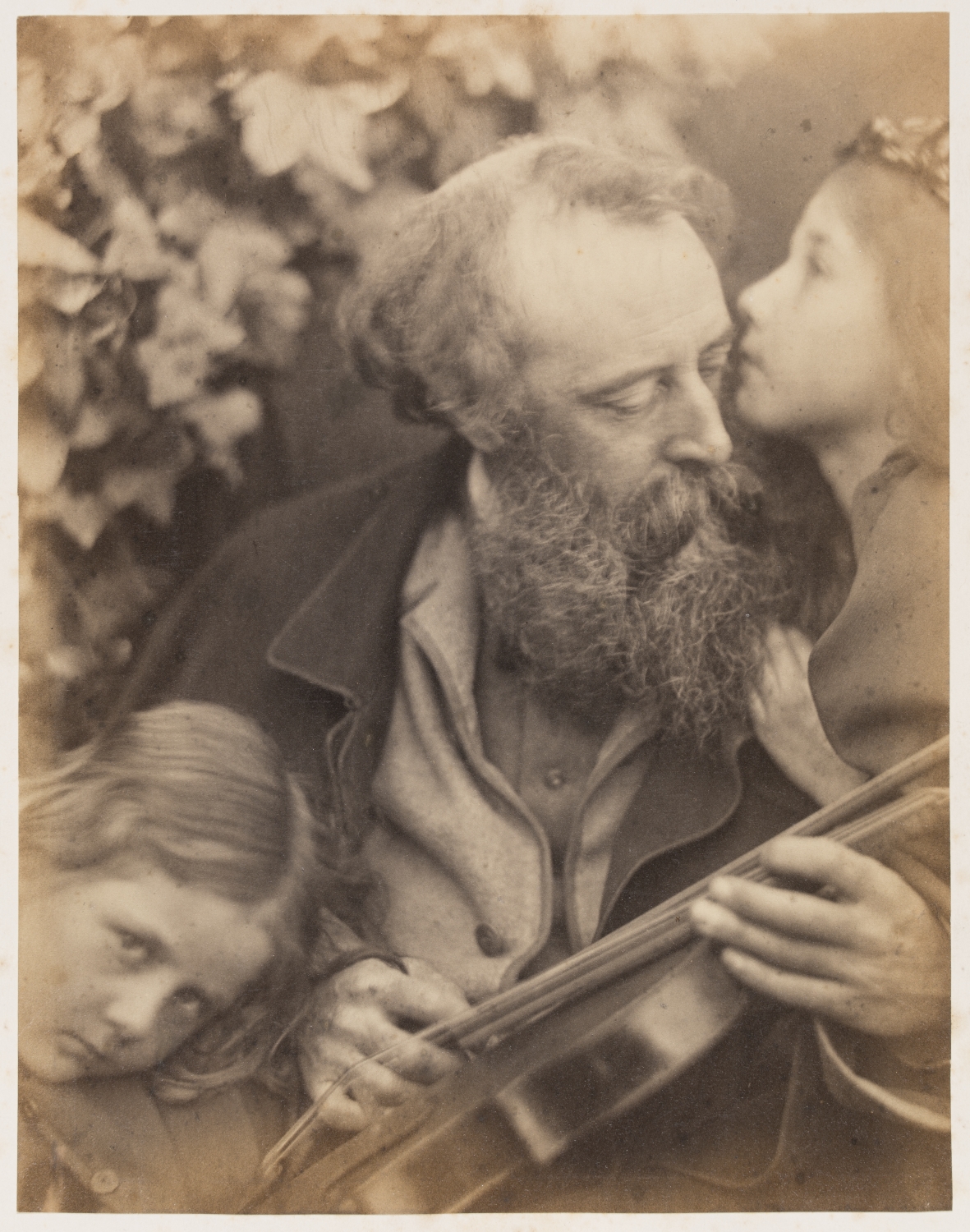

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Whisper of the Muse, 1865, albumen print © The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A, acquired with the generous assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Art Fund. Museum no. RPS.1262:1-2017

KG: In the same way, I prefer to think of her domestic duties not as something she had to transcend but instead as an integral aspect of her life. In fact, her first camera was a gift from her daughter. To be sure, Cameron occupied a relatively privileged position—she employed live-in maids who shouldered much of the burden. She was also fortunate to have the support of her family, which she acknowledges in Annals of My Glass House, writing that her “habit of running in to the dining room with my wet pictures has stained such an immense quantity of Table linen with Nitrate of Silver indelible Stains that I should have been banished from any less indulgent household.” But I also don’t know if she would have become the important artist that she did without the skills she honed as a hostess, household manager, and mother.

“From the first moment I handled my lens with a tender ardour, and it has become to me as a living thing, with voice and memory and creative vigor.”

Julia Margaret Cameron, Annie, 1864, albumen print © The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A, acquired with the generous assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Art Fund. Museum no. RPS.111-2017

LL: What are your thoughts about Cameron’s relationship to the photographic process? How did she learn it and maintain her practice?

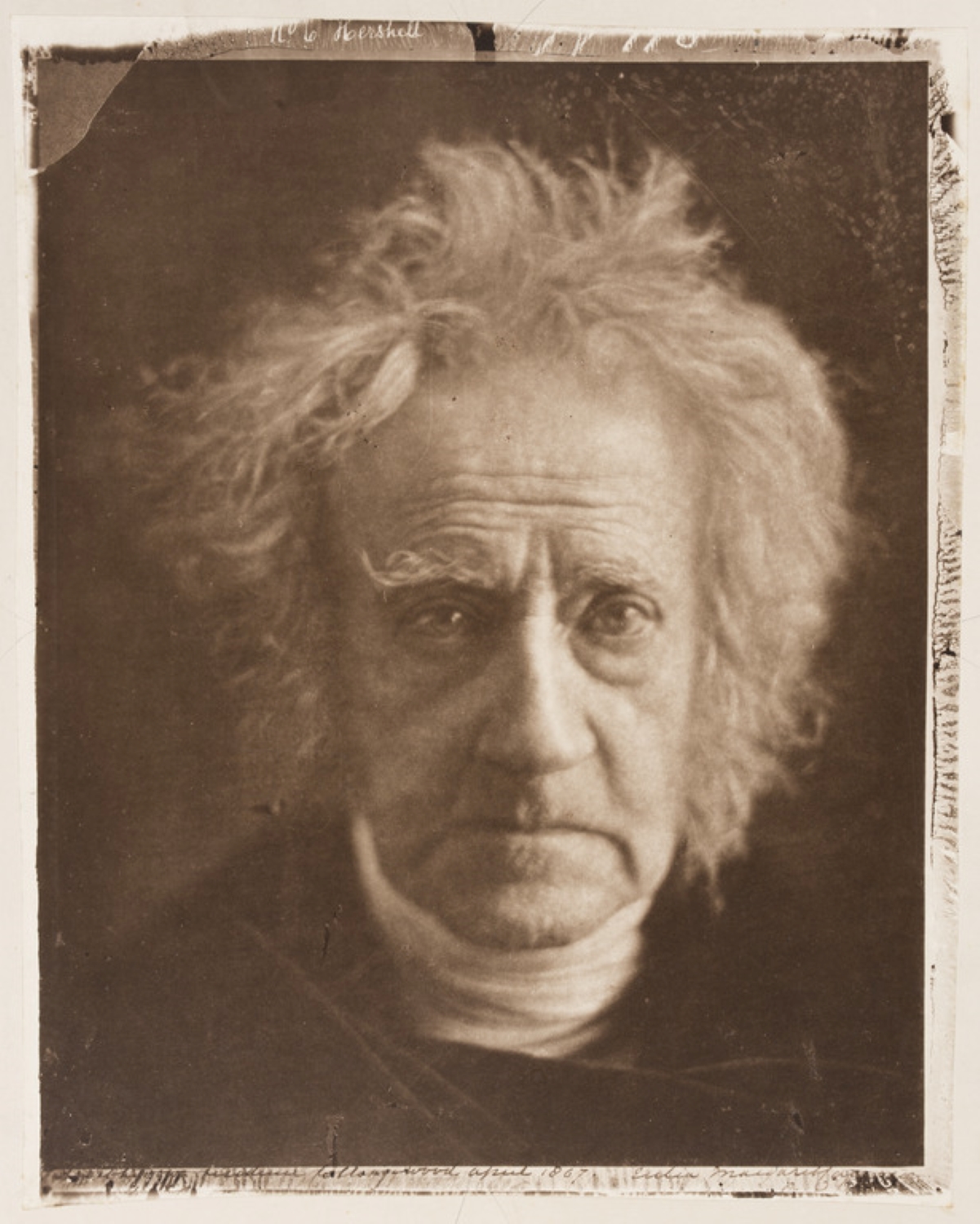

KG: It has been such a treat during this exhibition to spend time with Annals of My Glass House, which conveys such a sense of Cameron’s personality—she is charming, smart, and proud, with a sharp sense of humor. And as all good storytellers do, she knew when to exaggerate for effect! She writes in that memoir, “I began with no knowledge of the Art. I did not know where to place my dark box how to focus my sitter & my first picture I effaced to my consternation by rubbing my hand over the filmy side of the glass.” Yet we know that she wasn’t quite so ignorant of photography by the time she received her first camera, having posed for portraits, made prints, and perhaps collaborated with photographer Oscar Gustave Rejlander. She was also a close friend and consistent correspondent of Sir John Herschel, whom she had met while still a young woman. Herschel sent her photographs as early as 1842, when the technology was only a few years old, the same year that he also invented the cyanotype process. Cameron began making her own photographs over twenty years later, and given this background, perhaps it is a little less surprisingly that within weeks she arrived at her innovative and signature style with Annie (1864), the photograph she labeled “My first success.”

Julia Margaret Cameron, Sir John Herschel, 1867, carbon print © The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A, acquired with the generous assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Art Fund. Museum no. RPS.1154-2017

Julia Margaret Cameron, A Sibyl after the manner of Michelangelo, 1864, albumen print © The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A, acquired with the generous assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Art Fund. Museum no. RPS.736-2017

LL: Cameron actively promoted her work which was filled with references to art and literary trends of her day. Who was her audience? Was her iconography directed to the social elite or was it understood and enjoyed by the general public as well?

KG: This question gets at a central problem of context. Many of the titles and allusions of Cameron’s photographs would have been readily recognizable to her circle of educated Victorian Brits, but they aren’t to a contemporary American audience—including me! But understanding the other art forms that Cameron was engaging with is central to the exhibition, so I used a few strategies to try and bridge that knowledge gap, including reproducing paintings and lines of poetry that Cameron was referencing on the labels. We are also the only venue on the exhibition’s international tour to introduce paintings from our own collection into the installation. Enabled by our outstanding European collection, these inclusions reflect both the artwork Cameron admired and the output of her contemporaries, hopefully giving visitors a fuller appreciation of the lively artistic conversation across time and media that Cameron took part in.

Julia Margaret Cameron (English, b. India, 1815–1879), Beatrice, 1866. Albumen silver print from glass negative. Image: 13 3/4 × 10 3/4 in. (34.93 × 27.31 cm). Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of the Sheldon M. Barnett Family, M1986.40

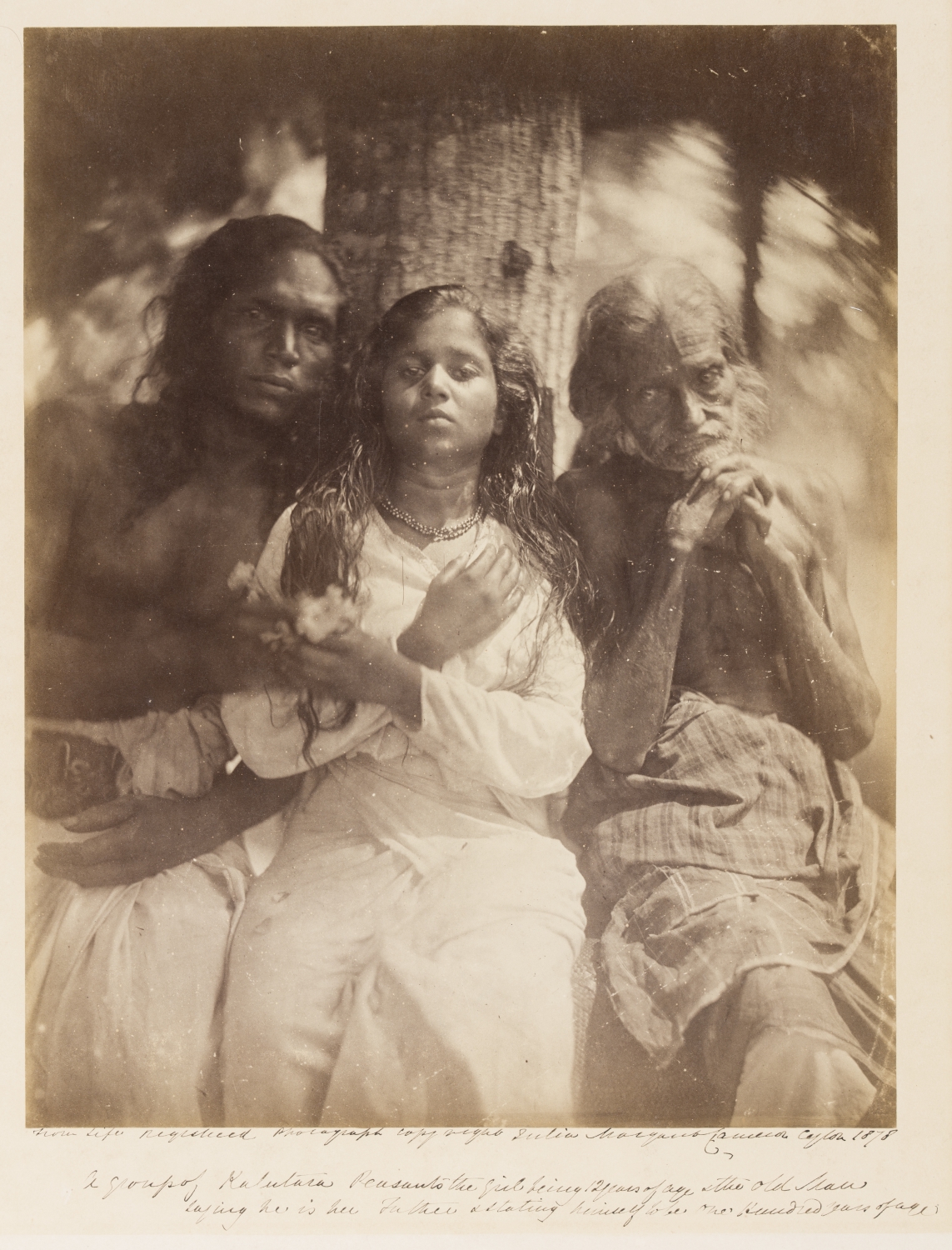

LL: Cameron photographed during the zenith of British Empire. How did her images reflect this socio-political state of affairs?

KG: This is such a great and complicated question! I’ll answer in two parts. First, the exhibition gives a sense of just how personally enmeshed Cameron was in the project of the British Empire through her portraits. She was born in India because her father was in government there; she convalesced from an illness in South Africa, where she met her future husband (who also had a role in the colonial Indian administration); her eldest son worked for the governor of Barbados; and she and her husband died in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where her family owned coffee plantations. Many of her portrait subjects are women and men similarly positioned in Britain, and occasionally the colonized themselves. Second, for a deeper answer to the question I want to point to the work of scholar Jeff Rosen, whose 2016 book Julia Margaret Cameron’s “Fancy Subjects”: Photographic Allegories of Victorian Identity and Empire investigates the way her tableaux reinforce British national identity, including its territorial expansion across the globe. (He just published another book on the topic, focusing on Cameron’s response to the 1857 Indian uprising against the British East India Company, called Julia Margaret Cameron: The Colonial Shadows of Victorian Photography.)

Julia Margaret Cameron, A Group of Kalutara Peasants, 1878, albumen print © The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A, acquired with the generous assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Art Fund. Museum no. RPS.1093-2017

LL: How does the exhibition reveal her importance to a contemporary audience?

KG: While working on this show, a few colleagues and I had to keep reminding ourselves that these photographs were made 160 years ago! That’s partly the nature of photography—its amazing ability to freeze a moment and create a connection across decades, or even centuries. But that reaction is also in response to Cameron’s photographs being intentionally a little “out of time.” Many of her portraits don’t show Victorian clothing or hairstyles, instead featuring sitters with tunics and loose hair. She believed in de-emphasizing the particular to get at something more elevated or universal. Although contemporary visitors are multiple generations removed from Cameron and her circle, I think her fascination with and beautiful presentation of her fellow humans remains relevant to us all.

Julia Margaret Cameron, I Wait, 1872, albumen print © The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A, acquired with the generous assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Art Fund. Museum no. RPS.1297-2017

***

Arresting Beauty, organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, will be on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum through July 28, 2024. The catalogue is available through the Museum Store as well as widely online.

Kristen Gaylord is Herzfeld Curator of Photography and Media Arts, overseeing the research, preservation, and presentation of the Museum’s photography and new media collections. She came to the Milwaukee Art Museum in 2023 from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, where she organized exhibitions including Moving Pictures: Karl Struss and the Rise of Hollywood (2024), Stephanie Syjuco: Double Vision (2022), and Set in Motion: Camille Utterback and Art That Moves (2019), and toured the landmark photography surveys Christina Fernandez: Multiple Exposures (2023) and An-An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain (2021). Previously, Gaylord held various curatorial roles at The Museum of Modern Art, where she contributed to exhibitions and publications, as well as research and teaching positions in New York and California. She holds an MA, MPhil, and PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and Photography, Part 2January 22nd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and PhotographyJanuary 21st, 2026