Charles Shuford: Blue is For Boys

In the spring of 2023, one of my colleagues accidentally left a lab unlocked at the university. He mentioned that Charles Shuford, a former student of his returning after a long absence from school, was in the darkroom making cyanotypes that night. I volunteered to go back and lock up, with the intention of recruiting Charles for my Alternative Processes class. In the fall of 2023, I observed his dedication as he struggled to print cyanotypes on glass, spending countless nights in the lab. He even marked his all-nighters on the chalkboard until graduation. In the winter of 2023, he began this project “Blue is for Boys,” a complex and personal narrative using vernacular photographs of men to question what masculinity is. The individual faces of the men become less important than the uniform masculine gestures and the expectations placed on boys to emulate them.

Charles Shuford is a photographic and mixed-media artist born in Hickory, North Carolina in 1995. He attended Appalachian State University and graduated in May 2024 with a B.F.A. in Studio Art with a concentration in photography. Fascinated with everyday rituals, shared experiences, and finding aspects of himself in the images of strangers, Shuford’s introspective work addresses such themes as sentimentality, aging, loss, and self-discovery through observation of the outside world. While he primarily works with analog photographic processes, he has also incorporated text, collage, assemblage, papermaking, and sculptural elements into his work, pulling from his extensive collection of found photographs, trinkets, and ephemera.

Shuford has shown work in a handful of exhibitions and publications, and has recently stepped into the world of curation with Watches the Clouds Roll By, a group-curated exhibition at the Appalachian State University McKinney Alumni Center, Boone, NC, of works from the collection of the Turchin Center for Visual Arts, Boone, NC.

Although he initially moved to Boone, North Carolina in 2013 as a temporary measure while he attended university, Shuford fell in love with the Blue Ridge mountains and has been continuously living and working in the Boone area for ten years and counting.

Follow Charles Shuford on Instagram: @charlesshufordphoto

Blue is For Boys

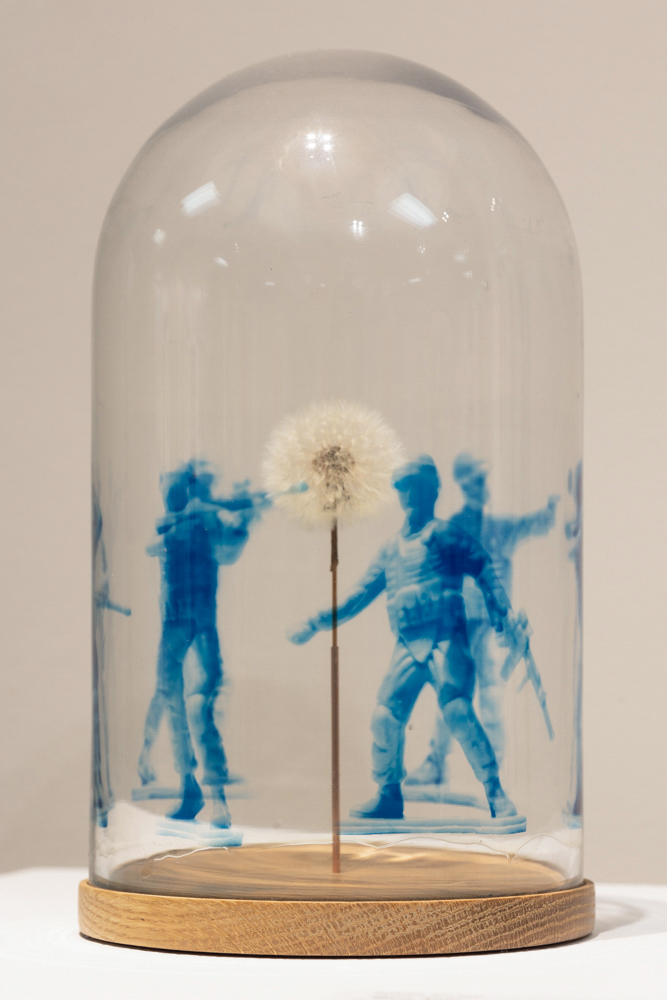

What does it actually mean to be a man? Between being mocked by the other boys on the elementary school playground for not wanting to roughhouse, to being chastised by my coach for crying when I sustained a concussion and a broken tooth in my first ever wrestling match, to deflecting endless condescending questions about how I could ever possibly support a family with a degree in art as opposed to a “useful” major like finance or law, I never really fit the mold of what a boy is expected to be. Growing up, the men I would see portrayed as heroes on T.V. were professional athletes, soldiers, police officers, politicians, wealthy business tycoons, or suave ladies’ men: imperious and aggressive figures whose modus operandi seemed to be to attain status by conquering and dominating others. Despite my parents’ and Mr. Rogers’ best efforts to raise me to be gentle, kind, and conscientious, I was not immune to the pressure to conform to the prevailing notion of “real” masculinity, and that led me to feel like I was fundamentally inferior to these hyper-masculine icons.

From a young age, boys are told to toughen up, to look out for themselves over others, and – above all else – to never show weakness. These lessons which are passed down through patriarchal culture dictate what clothes boys are supposed to wear, how we should act, what toys we are allowed to play with, and what jobs we should pursue. We are taught to put up a facade to conceal our feelings, alienating ourselves from our own humanity as well as from those around us. Ultimately, men are expected to fall in line and conform or else be ostracized. These rules are so ingrained in our culture and in our own minds that many men are left ignorant of who they are as individuals, leaving them truly without a sense of self at all in their absence.

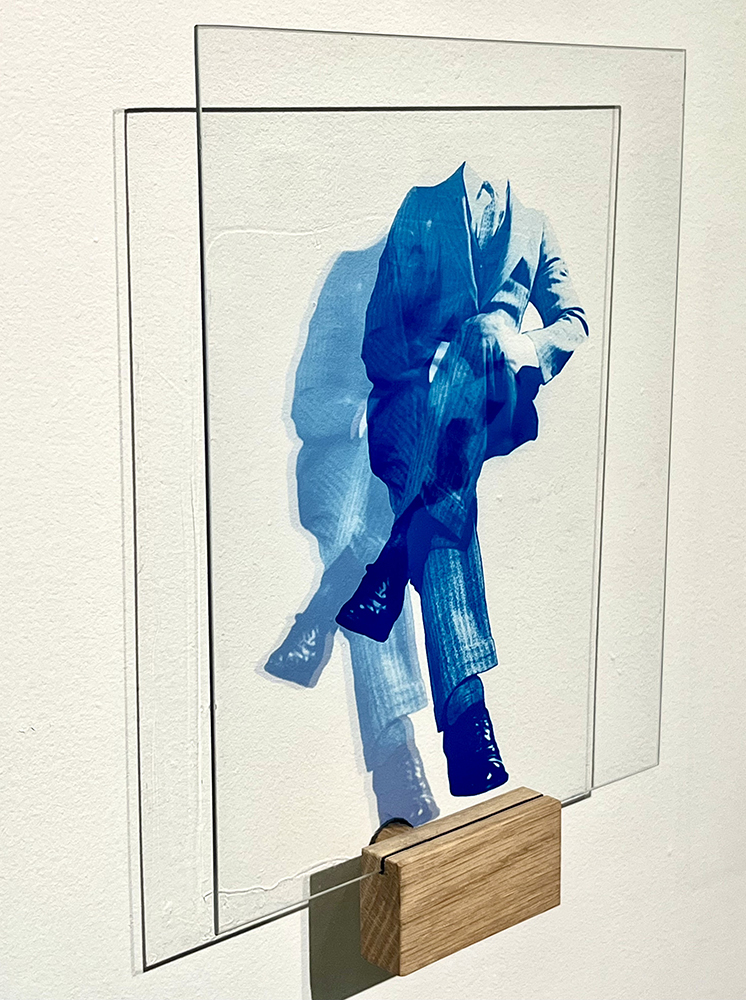

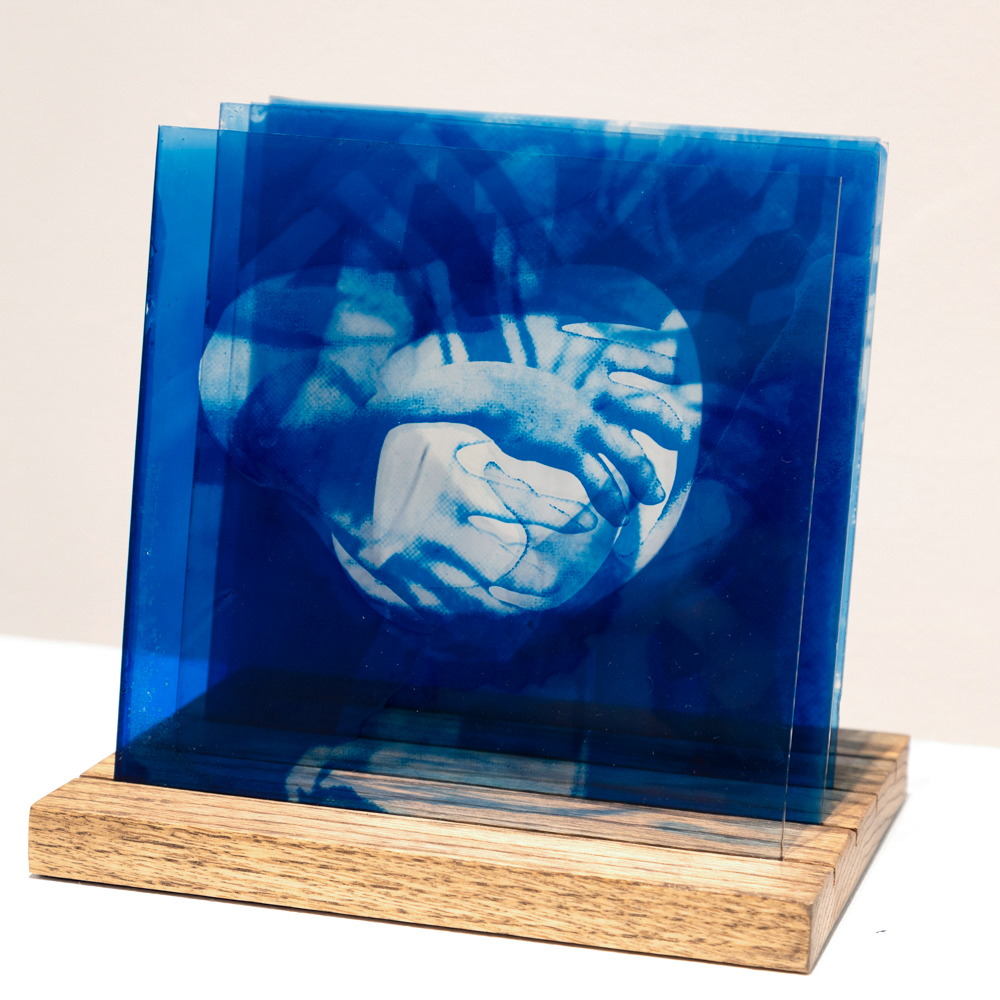

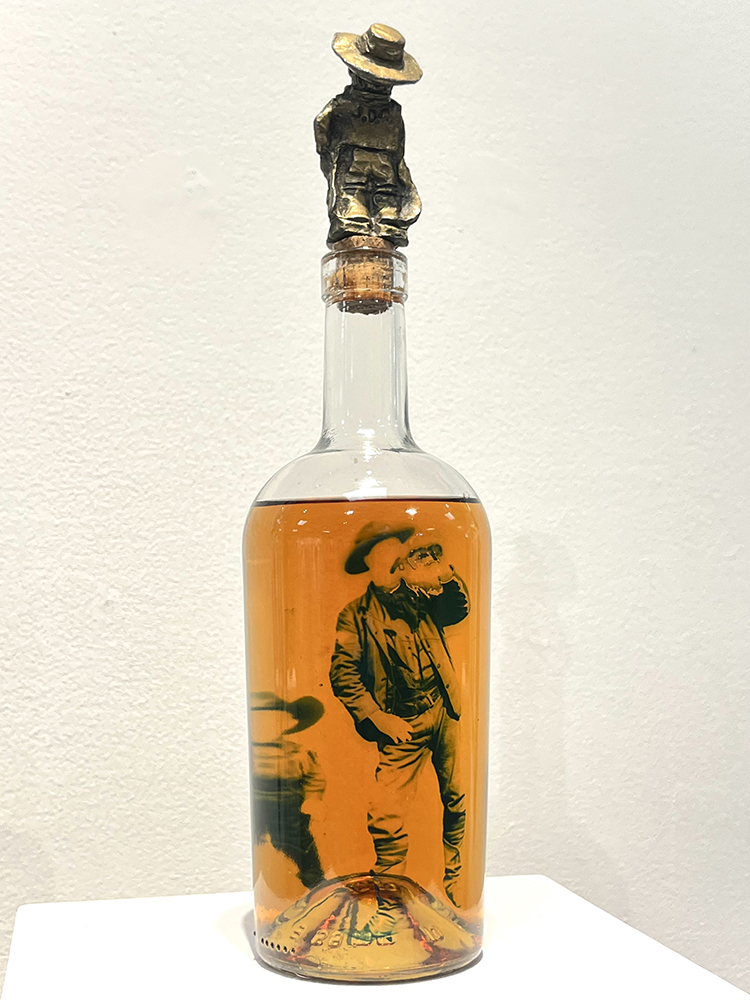

This work investigates the rigid conformity which patriarchal masculinity expects of men and how these expectations alienate men from intimately knowing themselves. Building on the work I have been making from found photographs since 2016, this work predominantly features appropriated images from found vernacular photographs which have been reduced down to the masculine symbols they contain. Despite coming from locations and time periods far and wide, the images are unified by the sameness of their visual characteristics, namely the composition of the photographs, the gesture and posing of the subjects, and the outfits those subjects wear. The photographs themselves adhere to certain conventions in the same way that men are expected to in everyday life. I chose to print these images using the cyanotype photographic process which is characterized by its distinct blue coloring and renowned for its archival longevity, both aspects which allude to the longstanding gender roles that the work addresses. The images are printed onto glass, representing the cold, hard, yet fragile nature of the masculine facade and highlighting the void of repressed self-knowledge that lies behind it. For me, this work serves as a way to dissect and examine these patriarchal notions in order to understand what roles they play in my life as I strive to unlearn decades of conditioning and re-discover myself as an individual.

GB: Talk about your childhood and your journey to photography?

CS: When I look back on all of my core childhood memories, one of the omnipresent elements of those is the image of my father shuffling around with a camcorder or a point-and-shoot documenting the occasion. Dad went to school for T.V. production, spent decades working on nightly cable news sets, and was the single coolest person in the world to me when I was a little kid, so by the age of five or six I was eager to absorb any of the snippets of photographic knowledge he was willing to share with me. He gave me my very first lessons on composition and was an exceptionally good sport whenever I’d grab a disposable camera and waste half a roll of film on our family vacations. I really owe a lot of my enthusiasm for photography to him.

I entered high school in 2009 and enrolled in my first formal photography class the following year. I was lucky enough to go to one of the last public high schools in North Carolina to still have an entirely analog photo program at that time. When we made photograms in the darkroom on the very first day of class, I was immediately hooked on analog. Lomography was taking the internet by storm, and I fell in love with the experimental aspects of that style of photography. I bought a Holga and a Diana, and every day after school I’d go out on my bike and shoot a roll of film. I’d do all kinds of wild manipulations to my cameras and film just to see what the images would look like afterwards, from flipping the plastic lenses backwards to making “film soup” out of various household cleaners. Naturally that love for hands-on experimentation led me towards alternative processes. By the time I was 18, I was playing with chromoskedasic sebattier, making lith prints with leftover materials I found in the back of the darkroom cabinets, and raiding the chemistry classroom to make salt prints from scratch. I began working with cyanotype in 2014 and instantly began sensitizing every material I could get my hands on. Although I’ve continued dipping my toes into other processes since then, that beautiful prussian blue just keeps me coming back.

GB: Speak about your use of the vernacular photograph?

CS: My interest in vernacular photography started sometime around 2016 during my Junior year of college. I had begun to get really frustrated with the rigidity of the rules that were being taught to photography students and bored with the photographs I was making based on those rules. The same century-old formalist discussions about composition and exposure that helped establish photography as a legitimate artistic medium gloss over what is, in my opinion, the most important aspect of photography: the democratization of image-making. Everyone can be an image-maker, and people have been capturing images of the things that are most important to them from the moment they were given the ability to. Amateur snapshots, I came to realize, were particularly fascinating for me not just because of their technical imperfection which reminded me of my Lomographic roots, but primarily due to their unpretentious earnesty – an element all too often absent in the formalist “fine art photography” that I was being taught in school. As I started looking at vernacular photographs more intently, I started noticing a certain set of photographic conventions in terms of subjects, composition, and posing that work to portray a kind of banal idealism that unifies them, regardless of when or where they were made. I began realizing that the way these photographs look was less important than what the action of making and viewing them meant to the people who were present in the moment captured in the frame. Understanding this link between the photograph and memory, I aim to investigate the way that these vernacular photographs take on new lives once time inevitably separates them from the people who could give them context.

GB: Tell us about “Blue is for Boys” and how the series came about?

CS: In western society, boys are expected to fall into line as they mature and adopt a very specific set of behaviors, aesthetics, and ideals that emphasize power, dominance, strength, and detachment. Boys are taught from a very young age not to express their emotions or ask for help, but rather to “man up” and either deal with their feelings silently, or let them build up until they explode into anger and violence. These values have been passed down from generation to generation, not just by fathers or male role models, but also through popular culture. Look at the men portrayed as heroes on television: professional athletes, soldiers, police officers, politicians, wealthy business tycoons, and suave ladies’ men – imperious and aggressive figures whose modus operandi is to attain status by conquering and dominating others. The facade that we as men are encouraged to put up to conceal our inner selves can become so ingrained that even we ourselves lose sight of the complex, sensitive, loving human beings we are deep down. Because we fear being ostracized by patriarchal society, we alienate ourselves from our own humanity as well as from those around us.

Blue is for Boys is my response to the lifetime of criticism that I’ve received from men for not exactly fitting in with these traditional patriarchal ideals of masculinity. The series dissects and examines these ideals in order to understand what roles they play in my life as I strive to unlearn decades of conditioning and re-discover the individual that I myself imprisoned behind my own masculine facade. The title alludes to the color blue having become one of the pervading symbols for masculinity that infant boys are raised around, starting the process of conditioning them into societal gender roles from the very moment of their birth. I chose to use the cyanotype process for this series partly because of this strong association between blue and boyhood, but also for its renowned archival stability that relates back to the way the issues the work addresses have endured through the years, even in the face of feminist anti-patriarchal and gender equality movements. The images are printed onto glass, representing the cold, hard, yet fragile nature of the masculine facade and highlighting the void of repressed self-knowledge that lies behind it.

GB: Tell us about your process and your use of cyanotype?

CS: The imagery for this series predominantly originates from my collection of found vernacular photographs, but it undergoes quite a transformation from the source photographs. I’ll spend hours sorting through my collection looking for images that not only resonate with me and feature the subjects I’m seeking, but are composed in such a way that they will work well in context with each other. For this series, my goal is to emphasize the cultural phenomenon of patriarchal conformity and the symbols through which it manifests itself rather than to create narratives about individual men, so I strip away all other elements from the images other than the symbols I want to focus on. This results in an aesthetic that simultaneously references paper dolls and microscope slides, highlighting the analytical nature of this work as well as the gendered divisions our society assigns to every part of life, even children’s toys.

To create my cyanotype prints on glass, I start with a digital negative on acetate which has had a contrast curve applied that is matched to the sensitivity of the cyanotype emulsion. I coat my glass plates with a mixture of classic cyanotype sensitizer made from potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate and gelatin. While I’m far from the first person to use this process on glass, none of the instructional guides on the internet make it clear exactly how much tweaking the gelatin cyanotype emulsion takes to get right. Likewise, getting the glass perfectly clean before coating is deceptively difficult. Once I figured out the importance of temperature control for getting an even coating, both with preheating the glass before coating to keep the emulsion from solidifying too fast and keeping the emulsion warm enough to keep it in a liquid form, but not so hot as to damage the sensitizer, I started seeing some much more consistent results. Washing the prints after exposure is equally temperamental, requiring the coldest water possible and very little agitation to keep the emulsion from detaching from the glass. I learned the hard way that tricks that work on paper like adding hydrogen peroxide to the wash water to instantly oxidize cyanotypes to their final tone will not work with the gelatin emulsion, causing bubbling and lifting of the darkest areas of the print. I had easily twice as many failed prints as successes when I first started this process.

GB: Talk about the record player for exposing cyanotype on the bottles?

CS: Ever since I had my first successes printing on glass I had had the idea to try and print on three-dimensional surfaces, but I struggled to figure out an exposure solution that wouldn’t result in hot spots and uneven exposure or require me to figure out a way to rig up multiple UV lamps in a studio with very little counter space and even less convenient access to power outlets. I think the inspiration for using a turntable came from watching ceramic artists in the clay studio across the hall from the darkrooms at App State throwing pots on a wheel. I saw how little they needed to move their hands to affect the entire form of the spinning clay, and I realized that I could get an even exposure on a round form just by keeping it spinning in front of the light source. I tested the idea out by building what our mutual friend and collaborator Addison Brown dubbed an “exposure rotisserie” using my record player from home, a small UV LED lamp, and a foil-lined cardboard box. It worked perfectly on my very first try. Shaping the digital negatives to wrap around the curved surfaces without distortion and coating the 3-D objects with the gelatin cyanotype emulsion were significantly more difficult challenges when it came

GB: Do you think the definitions for masculinity are changing?

CS: While I do think the specific definition of masculinity is perhaps softening slightly, I feel like there has been a much greater change in the amount of significance that people give towards living up to that definition in the first place. The strides towards acceptance that the queer community has made in the last two decades have certainly led to a broader understanding of the gender spectrum as a concept, so we’re starting to see a cultural shift towards accepting that being a man is so much more than simply being a monolithic expression of masculinity. To be a well-rounded individual, you really do need to have a balance of masculine and feminine traits and a secure enough self-image to be able to ignore all the voices telling you you aren’t enough of anything. It really gives me a lot of hope to see young people having judgment-free discussions about gender identity and expression, even if conservative backlash against those topics has become more vitriolic.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025

-

Mary Pat Reeve: Illuminating the NightDecember 1st, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025