Photographers on Photographers: Yogan Muller and Ryan McIntosh in conversation with Robert Adams

Ryan and I engage in a conversation around our collaborative project, ‘Tracy Hills,‘ an in-depth exploration of nearly three years the eponymous new master-planned community in the Central Valley near San Francisco. With the 50th anniversary of The New West drawing near, we reflect on the New Topographics legacy and reconsider the topics and issues central to the corpus, bringing in our ecological concerns.

Ryan McIntosh, born in California in 1984, is a Los Angeles-based artist and photographer. He received his MFA in Printmaking from Rhode Island School of Design, and his BFA in Photography from University of Arizona. Ryan’s recent work revolves around mankind impact on the natural environment and the changing landscape of the Southwest. He photographs exclusively with an 8×10-inch view camera, committing himself to producing only handmade silver chloride contact prints in the traditional wet darkroom processes.

Follow Ryan McIntosh on Instagram: @ryanmcintosh__

Yogan Muller: I thought the gorgeous print you gave me was an excellent point of departure. Before we start, let me express how I appreciate this thoughtful gesture. It means a lot to me, our friendship, and our three-year in-depth explorations of Tracy Hills. On the other hand, I apologize if I got in your frame despite your repeated warnings, which I didn’t hear! You shot this picture in June 2024 while we were photographing the Corral Fire aftermath. The blaze swept through the hills and prompted the evacuation of Tracy Hills, the new master-planned community we have been photographing further down near the Central Valley floor. I wonder what went through your mind as you walked the charred hills?

Ryan McIntosh: I recall making this photo while I was walking towards our car to grab a snack. I turned around to observe the blinding bright silvery grasses which blew in the wind, untouched by the fire. I noticed you standing off on a nearby hillside, not using your camera but just absorbing the miles of scorched black land from the recent fire. It took me a few minutes to set up my 8×10 camera, compose an image, focus the ground glass and load the film holder. By the time I fired the shutter, you remained a statue in the landscape. I think an appropriate title for this photo may be “The Observer In a State of Observation”. We often are photographing with such rigor and intensity that we sometimes forget to stop, step away from the camera, and just take in our surroundings. Was there something in particular you remember experiencing at this moment?

YM: It’s a remarkable photograph, too. It includes the hills, which gave Tracy Hills its name, and suggests the former land usage: grazing ground for cattle. It also reveals how much of a fire-prone area those hills are. I recall pondering topographies, scales, and distances. British anthropologist Tim Ingold once noted that although we are situated within our body in a landscape, our mind wanders and “touches” distant landscape features through walking and observation. I stood there, soaking it all up and trying to make the charred hills material for my art. There was a vastness but also myriads of small scenes and configurations at our feet.

RM: This photograph of yours, “Weeds on newly graded terraces, Tracy Hills” is reminiscent of a photograph I’m particularly fond of by Robert Adams, titled “Santa Ana Wash, Next to Norton Air Force Base, San Bernardino County, CA, 1978”. Although quite different photographs, the quality of light and almost artificial quality of the plants gives me a feeling that this place could be a Garden of Eden. The plants have this sense of innocence and fragility, yet are faced with undeniable misery and death of growing in this difficult terrain.

Much like both of our photographs, your work is in dialogue with generations of photographers who have come before us, such as Robert Adams who we both admire. When you’re in the field photographing, do you ever consider these parallels we may create, knowingly or unknowingly, with our photographs?

YM: I photographed those weeds for all the reasons you pointed out. I also wanted to look at the resilience of the natural world. One would think that after being aggressively bulldozed by huge grading trucks day in and day out, no non-human lifeforms would thrive on this land. And yet, those plants are growing from seeds dispersed by the wind probably years ago. They are coming to life, reestablishing a synergetic ecosystem.

It’s funny that you highlight pictures Robert Adams made in the Santa Ana Wash, for Los Angeles Springs, I assume. The one picture with a white spheric object in a dry, littered riverbed left a profound imprint on me. I can practically feel the overbearing pressure of the sprawling city creeping into the tilted frame. Things are going awry in this picture.

Those weeds are growing on graded expanses that are part of the second phase of Tracy Hills, on the other side of the 580 freeway. Shockingly, they appeared in total abandon and decay, thus standing in sharp contrast with the fast-paced enterprise of building houses up there. Their rectilinear edges and terraces were crumbling.

RM: I feel more akin to Frederick Sommer than to any other photographer, likely from being exposed to his work in high school while growing up in Prescott, AZ where he lived at the time. I feel he photographed decay better than any other photographer. His photograph of “Coyotes, 1945” was one of the first I saw by him and it still haunts my mind today, in a good way! I have an original print of the Coyotes hanging in my dining room and it brings me joy each day that I get to look at it.

This photograph from Tracy Hills of the cracked mud is an outlier for me because of its visually transient appearance. It begins to approach abstraction and depart from the world of true appearances. I aspire to make photographs that clearly represent reality, but the dried mud in this scene was so harshly bright that the contrast makes it take on an otherworldly appearance, yet the tumbleweed and workers’ footprints in the mud give a sense of scale.

RM: Although we have considered this project a collaboration, we have both focused solely on our own photographs and never made photographs that would be jointly attributed to both of us. Oftentimes we are working in close proximity to one another and will make wildly different photos, but on occasions we have observed similar scenes which result in uniquely similar yet different photographs. I find these comparisons to be interesting, because they both highlight different nuances and characteristics of the landscapes. On our recent visits, I found myself seeing a lot of “Yogan Müller photographs” in the field. Sometimes I’d point things out to you, but usually I just hope you stumble upon what I saw and find it compelling enough to make a photograph.

YM: I am grateful you showed me Sommer’s work. In the coyote picture, we as viewers are looking down on cadavers, the physical vessels, while their souls have escaped into the ether.

I want to bring up one of my favorite images of yours.

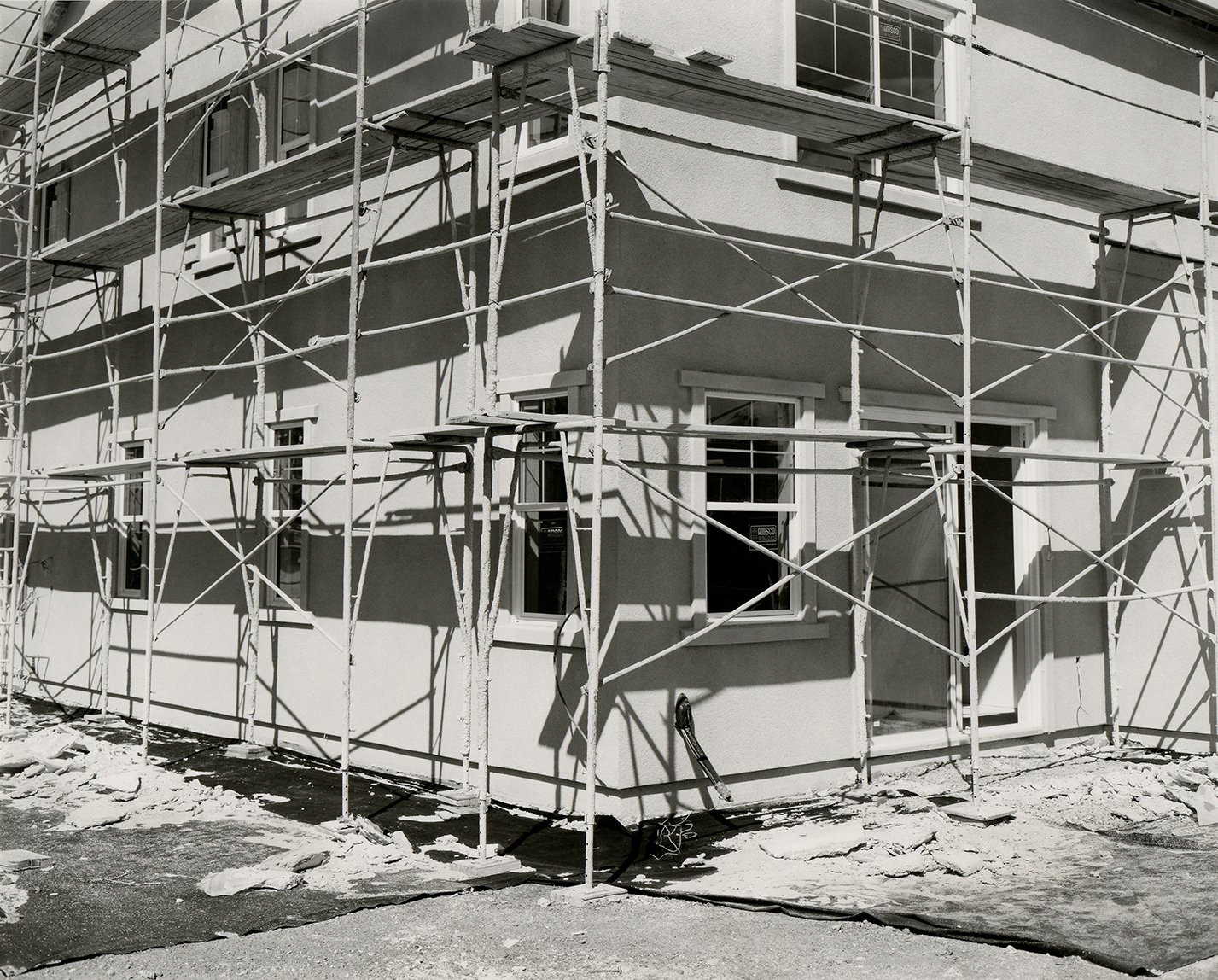

How you photographed this new row of houses under construction makes the conversation enter into the 21st century and grapple with climate change. Showered by the sharp desert light, the structures look so vulnerable to the environment that supports and surrounds them. The skewed shadows and the triangular-shaped battens in the center frame bring it all together for me. It is as though this entire row of houses was resting on this single pressure point quite precariously. Not only does this picture spread light on the expedience of the whole enterprise, but it also suggests, in such a compelling way, how wrongly configured the houses are for the local ecology.

YM: As for the collaborative nature of our endeavors, while the means we use and the resulting images are different, it’s clear that we have approached and photographed Tracy Hills with a shared concern, while being drawn to the same motifs and influenced by the same photographers. As I walked the landscape, I, too, saw a lot more of “Ryan McIntosh’s images.” Your meticulous treatment of scales, planes, space, and geometry prompted me to solve more finely layered photographic equations. Conversely, you’ve turned your lens to objects, geometries, textures, and imprints a lot more, abstracting them from the place as I quite compulsively do. We bounced photographic ideas off each other, enriching our photographic syntax and style, trip after trip.

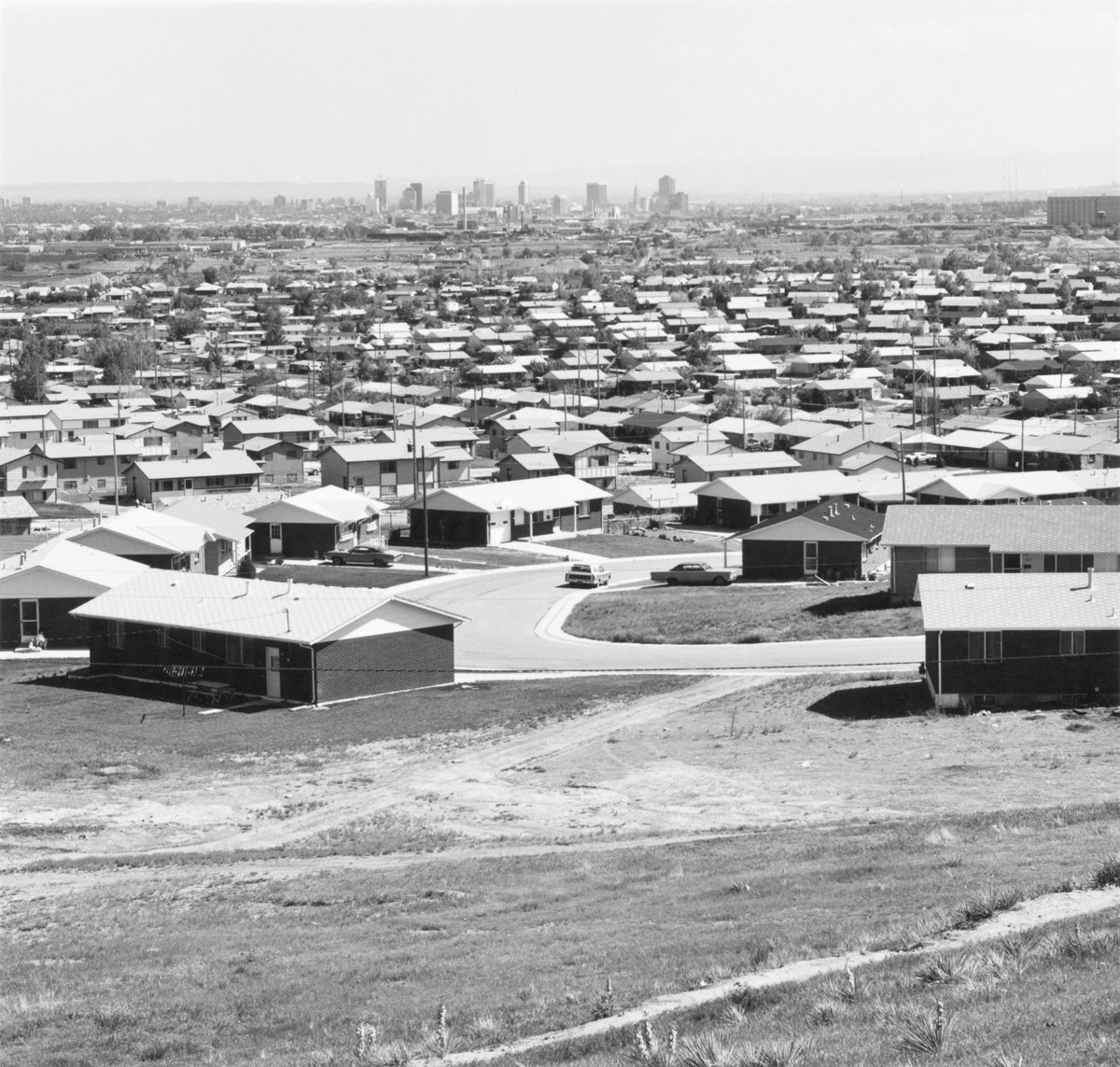

Delving deeper into influences, it’s the 50th anniversary of The New West by Robert Adams. In a review of this seminal book, Lewis Baltz noted:

“The new suburban areas of America pose an array of novel problems for society. Conceived in expedience for the sole purpose of maximum profit, pathetically dependent on the automobile, these new cities have disposed themselves formlessly along the frontage roads of every interstate highway. Posing an ecological threat which we are only now beginning to grasp, this new human sprawl is also ultimately as alien to urbanism as it is to the land it consumes.’’

Tracy Hills is a carbon copy of what Baltz describes. The building materials, standards, and techniques might differ, but the phenomenon is identical. On the other hand, our knowledge of the ecological threat Baltz alludes to has grown considerably since the 1970s. From 1974 to 2024, I’d like to hear your thoughts on our current condition, bearing Baltz’s quote in mind, and how you approached it photographically.

RM: I’d like to reference a photograph by Lewis Baltz “Tract House #4, 1971”, as this body of work parallels what we have witnessed in Tracy Hills with the same banal home construction, stucco walls, aluminum windows and dirt yards. Fifty years later, and not much has changed. The houses Baltz photographed were all brand new construction, yet already appeared in a state of decay. The same sense of degradation and disarray can be seen in many of our photographs, such as the one you shared above where the walls almost feel to be bowing under their own weight. Even now that a large portion of the Tracy Hills development is completed and inhabited, the houses don’t feel new to me. The plastic siding on the houses are beginning to fade from the sun, the decorative plants have turned brown from lack of water and the desert dust settles on everything, turning all colors to muted tones of what they aspire to be.

Robert Adams made a profound statement when he called his book “The New West”, as it marked a pivotal moment of change. I assume he longed for simpler times and a return to a time before the land became sprawling with freeways, billboards, tract homes and strip malls. Adams witnessed the birth of the suburbs. Today, these areas he photographed are no longer recognizable as the suburbs, as they have been fully incorporated into the metropolitan city. I was not born when Adams documented the New West, so the images Adams portrayed don’t necessarily convey much urgency or concern to me, but rather a sense of nostalgia of my childhood town.

RM: While Adams documented the creation of the suburbs in Colorado, what we have witnessed in Tracy Hills is the creation of the exurbs, which exist far out beyond the suburbs. Tracy Hills has promised a viable housing solution to those who work and commute into San Francisco/San Jose, which is 65 miles away and a 1.5 hour commute by car each way. The development is completely insular and disconnected from any culture or identity of the nearby cities.

My initial draw to photograph at Tracy Hills came out of sheer curiosity when I saw the “Future Villages – Coming Soon” billboards along the freeway. I’ve never had any desire to photograph housing development or construction, but once we started making photographs there I began to see the visual success the images had. I often photograph things that I don’t understand, as the process of photographing helps me understand them more clearly. The simple act of seeing also becomes a form of acceptance. For me, these photographs are a personal journey of understanding and acceptance of what we have witnessed.

YM: I am glad you highlighted a Tract House by Baltz. I am no construction expert, but it is so striking to see the similarities in terms of materials, expedience, and design.

YM: On the motif of stucco, we both turned our lens to freshly stuccoed houses probably because they represent such an architectural “staple” here. Those structures seem to emerge from a special kind of primordial ooze, turning into the consolidated reality of a house.

YM: The distinction between suburbs and exurbs is important. Rapid urban expansion in the last fifty years even made scholar Lincoln Bramwell coin the term “wilderburb.” It describes developments that are so far removed from dense urban centers, that they expose dwellers to wildlife and wildfires. Suburbs, exurbs, wilderburbs, that’s how far sprawl has gotten.

YM:As an ecologically-minded individual and photographer hailing from Europe, I deeply resonate with what you said about The New West and the longing for simpler times. In Adams’ pictures, this longing coexists with the painful recognition that the built environment will continue to ravage the landscape, irrepressibly so.

Our work exudes a heartfelt appreciation of and reverence for the seminal series we’ve brought up in this conversation. A point of departure I see is how much we imbue our pictures with the sense of urgency you mention, the urgency of climate change, droughts, and fires, that is. I see a lot of this in our two pictures below.

YM: Bluntly, our work addresses the anachronistic nature of Tracy Hills. In a lot of pictures, there is a sense of “climate change is settling in.” That’s a throughline that further unites our takes.

RM: Over the last several years of photographing at Tracy Hills, there are two singular photographs by you and I which I’ve found exceptionally successful and important to the series, and they are two images that show a physical presence of self. The photo of my shadow looking down into a massive drainage ditch, and the photo of you holding a spiral of nails. Rarely, if ever, have I included any sense of self in my photographs. Making this photo felt technically incorrect, as I typically try to avoid my shadow or reflection accidentally ending up in the frame. These two images convey two crucial things to me, and that’s a sense of concern and a sense of courage.

I truly feel the best photographs through history are so successful because they contain a sense of concern and courage put forth by the photographer. With documenting Tracy Hills, we are following in the footsteps of many other regarded photographers who have also turned their lens on similar subjects. It’s in my hopes that the work we made here can not only continue the dialogue they started, but further the discussion in today’s contemporary discourse.

During the process of this project I corresponded with Robert Adams by letter. In one of the last letters he wrote back to me, it read…

Ryan –

With shared hope, in this

broken world, for better

days and clearer vision …

Courage –

Bob Adams

Where his letter most resonated with me was the simple one-word closing… Courage. In all my life, I had never seen someone sign off a letter with the word courage. The courage to do what exactly? Courage is defined as ‘The quality of mind or spirit that enables a person to face difficulty without fear.’ Although we all face difficulties and fears every day which requires having courage, I interpreted ‘courage’ to relate specifically to our role as photographers. The simple act of making photographs requires an amount of courage to simply ‘see’ photographically. Some of this courage is granted to the photographer by just possessing a camera in hand, but much courage must be found within oneself.

Every time I make a photograph now, I ask myself… Did I put forth any amount of courage in making this picture? Not just physical courage in the field, but rather the courage to make photographs which challenge and push my photographic vision and artistic voice, and go above and beyond what has been made in the rich history of the medium.

YM: Including ourselves in photographs points to this rich history for sure. Reflexive photographs also express our presence and commitment. For me, they are a form of entanglement with our subject.

It took us a lot of courage to pursue this long-term project, returning to Tracy Hills. After trip #2 in October 2021, we almost aborted the project. You had lost all your pictures and felt utterly discouraged. I am glad I convinced you to shake it off.

It is courageous to stand on this event horizon where raw pictorial potential emerges, and it is our task to create meaning through a series of photographs.

I also received a thoughtful note from Robert Adams. He replied to a letter I sent him in June 2024 with a postcard referencing his exhibition, ‘The Place We Live,’ at Jeu de Paume in Paris in May 2014, where I first discovered his work. Likewise, he concludes with “Courage” and an elongated hyphen.

Yogan Müller is a photographer, first-generation graduate, and educator whose work engages with the ecological crisis and its impact on landscapes and communities. Yogan works with photography, photogrammetry, drones, the book form, and artificial intelligence to respond to the Anthropocene/Capitalocene. Research, critical approaches to landscape, fieldwork, and design are central to his process. After the unexpected losses of his father in February 2022 and his step-father in June of that same year–both were born and grew up in Algeria, métisse identity, belonging, and fractured roots are themes that came to the fore.

Follow Yogan Müller on Instagram: @yoganmuller

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Landscape ReEnvisioned Exhibition At the Monterey Museum of ArtFebruary 26th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026