Inner Vision: Photography by Blind Artists: The Heart of Photography by Douglas McCulloh

VocalEyes, a UK charitable organisation engaging with blind and visually impaired people and providing the best possible opportunities to experience and enjoy art and heritage through audio description have funded this week-long feature. We would like to thank Matthew Cock, the former CEO of VocalEyes who has a personal interest in photography. His support of the project made it possible for Louise Fryer, an experienced audio describer to interview the photographers. Karren Visser, one of the photographer’s featured was instrumental in initiating the idea to show photographs by blind artists on Lenscratch. Douglas McCulloh, Senior Curator and Interim Director of UCR Arts: California Museum of Photography was instrumental in the selection of photographs.

Photographs by Blind Artists: An Introduction by Douglas McCulloh

I’ve been obsessed with blindness and photography for almost three decades. I arrived carrying a clueless assumption: a blind artist making a photograph would be, literally, a shot in the dark. The images would be visual guesswork, chance operations. I placed blind and visually impaired photographers at the outer edge of photography. But I didn’t know anything then, and I was wrong about everything.

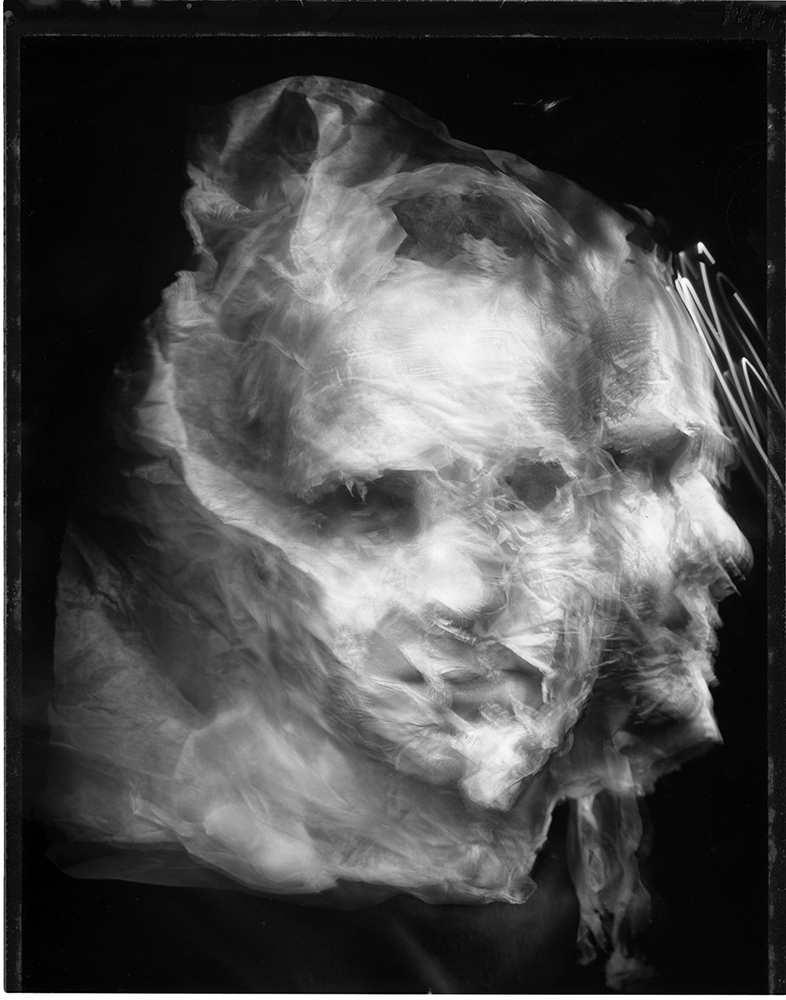

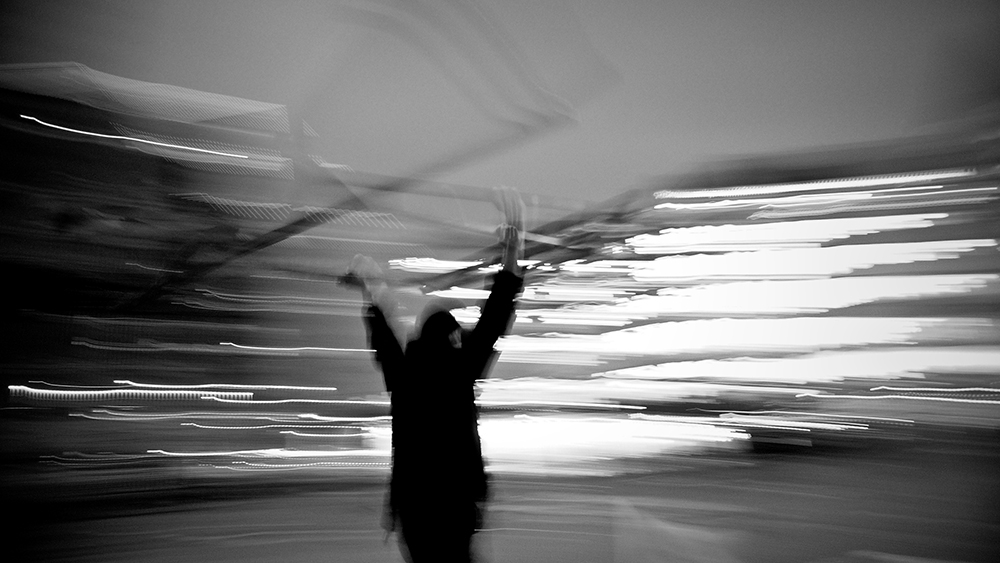

Here is the truth. Blind photographers operate at the heart of the medium; they are the zero point of photography. Blind photographers occupy the immaculate center—image as idea, idea as image. These artists privilege inner vision over mere outer sight. For them, as for the finest photographic artists, making images is, first and foremost, a mental operation. These artists visualize first, then make a photographic reproduction of the original that exists in their mind.

Photographs made by blind artists are inherently conceptual. “I feel very close to those who don’t consider photography a piece of reality, but rather a conceptual structure,” states Evgen Bavčar, an influential French blind photographer and pioneering theoretician.

Of course, a blind or visually impaired person making photographs is also a political act. By pressing the camera shutter, the blind lay claim to the visual world. When a blind person constructs a mental vision of the world, it means she too has an inner representation of external realities. All of this forces a reevaluation of our ideas about sight, blindness, and photography. Photographs by blind artists pose vexing questions, most troublingly for sighted photographers.

In the end, I curated an exhibition for the California Museum of Photography, the photography museum of the University of California: Sight Unseen: International Photography by Blind Artists. The exhibition, updated several times, is a traveling show. To date, Sight Unseen has appeared in 18 museums across the U.S. and in five countries. (The images that accompany this short essay are drawn from Sight Unseen.)

A Three-Part Framework and Some Pioneering Photographers

Blind and visually impaired photographers are as divergent and individual as any collection of art-makers and many operate in multiple modes. Nonetheless, here is a three-part framework to help analyze the work.

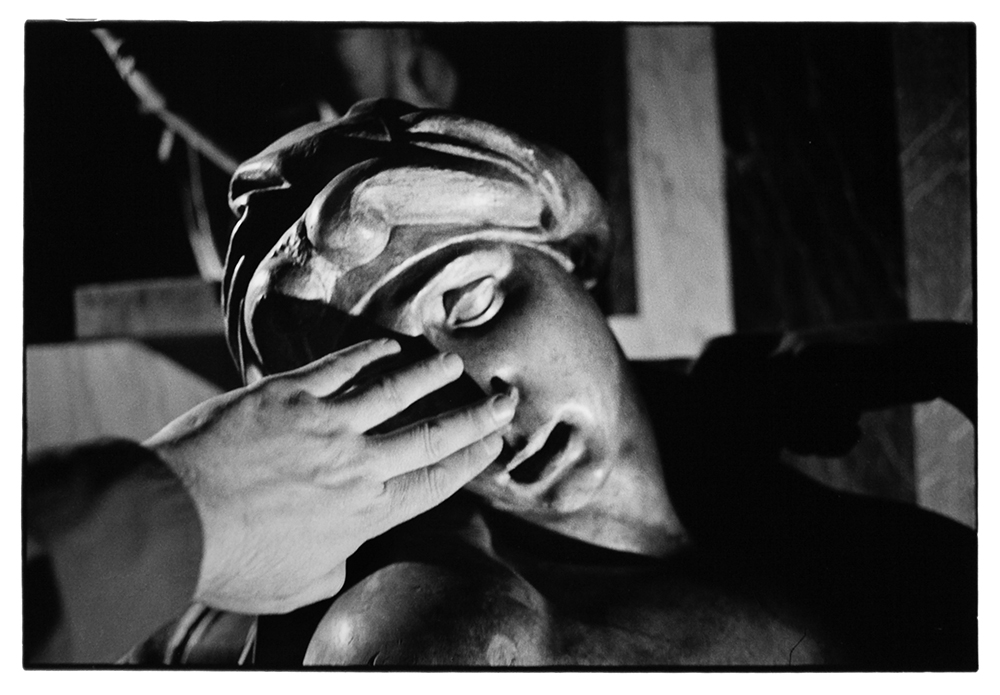

One group of these artists construct, curate, and maintain internal galleries of images. Then they use cameras to bring their inner visions into the world of the sighted. “I slip photos under the door from the world of the blind to be viewed in the light of the sighted,” summarizes Pete Eckert. For these artists, photography is the process of creating physical manifestations of images that already exist as pure idea. They make photographs to match what they imagine. The originals reside in their minds. A sizable list of blind photographers operate mainly in this mode: Evgen Bavčar (Paris), Pete Eckert (Sacramento, California), Alice Wingwall (Berkeley, California), Sonia Soberats (New York), and many members of the Seeing With Photography Collective (New York). Their images are elaborately realized internal visualizations first, photographs second.

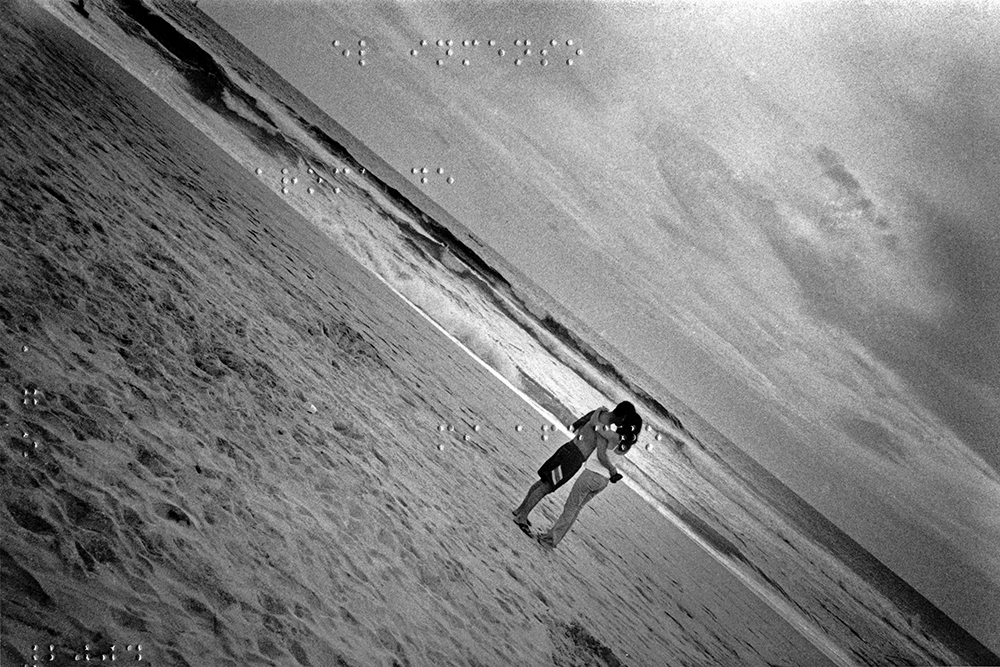

A second category of blind photographers deploys cameras to capture the outside world, but, being blind, operate free of sight-driven selection and self-censorship. Marcel Duchamp famously wrote of “non-retinal art,” art of the mind, of concept, of chance. These artists are engaged in non-retinal photography. The results are pure, unfiltered, and inherently conceptual. They operate beyond the logic of composition or the tyranny of the decisive moment. This group includes Henry Butler (New Orleans), Ralph Baker (New York); Gerardo Nigenda (Oaxaca, Mexico); Eladio Reyes (Havana, Cuba); Rosita McKenzie (Edinburgh, Scotland); Alex de Jong (Rotterdam, Netherlands); Pranav Lal (New Delhi, India). Unsurprisingly, many of these artists employ senses other than sight as pathways to vision. Henry Butler, an acclaimed blues pianist highly attuned to the auditory world, used sound to guide his street shooting in New Orleans. Rosita McKenzie speaks of images triggered by cues of sound, scent, or story. Gerardo Nigenda punched his images with Braille descriptions of sensory experiences—smell, touch, sound, the echo of a narrow street, the sun in a courtyard, the feel of an ocean breeze. Some, Alex de Jong and Pranav Lal among them, use new assistive technologies such as “vOICe,” a software program which translates images on digital camera sensors into verbal reports of composition, structure, design, and motion.

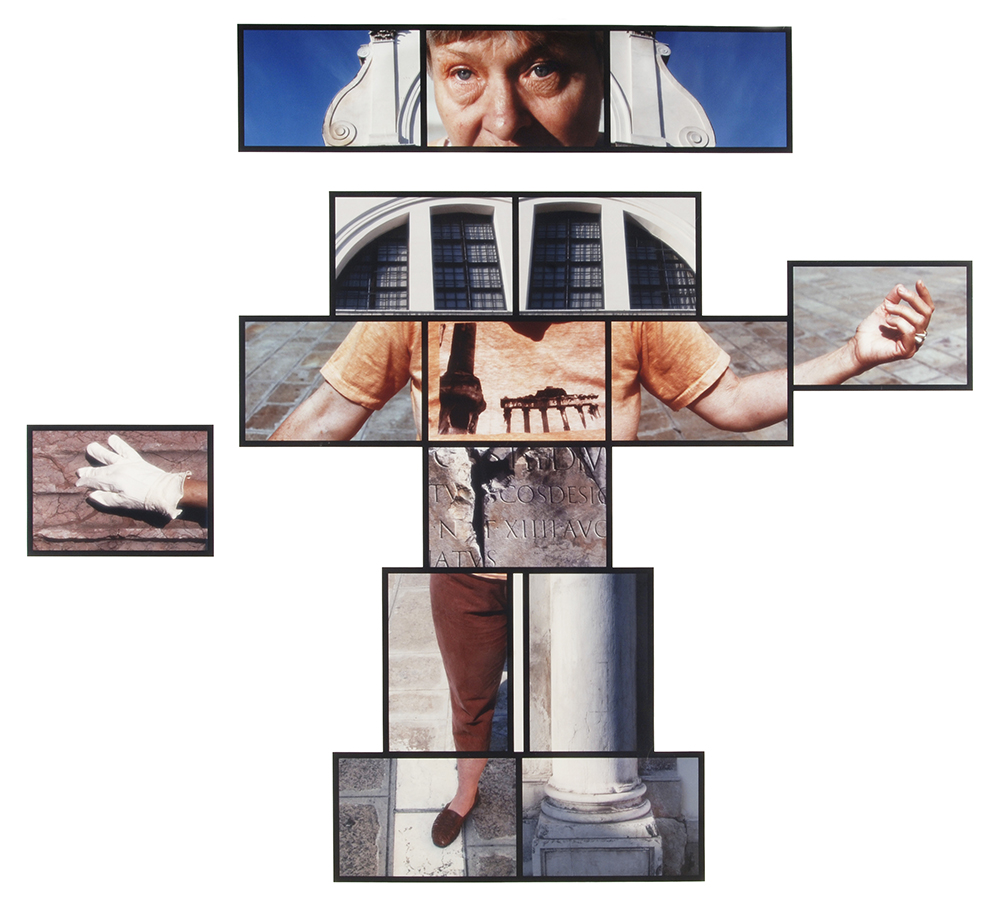

The third group is legally blind, but retain very limited, highly attenuated sight. Most photographers see to photograph. These artists photograph to see. They rely on seeing devices, cameras key among them, to maintain a tiny toehold in the visual world. Their visual space is made possible by mechanically enhanced sight. Bruce Hall (Irvine, California) was born with a fraction of normal physiological vision but uses digital cameras with high resolution sensors and sophisticated autofocus. When he looks into your eyes, it’ll be on the screen of his 40-inch Sony high-definition monitor. His photos literally occupy the gap between the limitations of physical sight and the desire for images. It’s double vision—“I take what I think I see, later I can see what I saw.” Among other artists operating a least partially in this mode are Annie Hesse (Paris), Michael Richard (Los Angeles), Kurt Weston (Huntington Beach, California), Karren Visser, Oxford, England). Susan Sontag calls photographs objects “that make up, and thicken, the environment we regard as modern.” By this logic, these artists lead hypermodern lives—they construct their visual world one image at a time using their own photographs as building blocks.

Implications and Questions

The striking, original, meaningful photographs by blind artists present a challenge to sighted photographers. The sighted live in a swirl of images, but has the modern barrage of visual clichés swept away our originality? Has our insistent sight and the torrents of visual pollution we are subjected to overwhelmed our vision? In the end, who is sighted and who is blind?

The conundrum is hard to deny. Quite evidently, there are now more images in the world than world to be in the images. The sighted are overwhelmed by a tsunami of photographs. We make them, collect them, curate them, and distribute them from our phones and laptops. We live within ever-deeper strata of visual iconography, sharing shifting signifiers up and down the layers of our lives. We clone cliches and imitate Instagram. Eventually, we mistake visual abundance for vision. Nobody can see anything. We are blind to our own blindness.

Beneath the entire subject is a philosophical question. “The matter isn’t how a blind person takes photographs,” states Bavčar, “but rather why he would want images.” The simple answer is that vision, even in the absence of sight, is a human need. “The human brain is wired for optical input, for visualization,” says Pete Eckert. “The optic nerve bundle is huge. Even with no input, or maybe especially with no input, the brain keeps creating images. I’m a very visual person, I just can’t see.”

Photography by the blind is its own intense, unapologetic world. These artists demonstrate that there is a crucial difference between mere outward sight and true inner vision. Great photographs, we are reminded, are not a product of the eyes, but of the mind, and the finest photographs by blind photographers conjure a breathtaking poetry. They create small pools of illumination within a sea of infinite dark. Filling even a tiny area of that night with light and meaning is all one can hope for, honorable work for a lifetime.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: The Photobooth Technicians ProjectNovember 11th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Rafael Hortala-Vallve: AUTOFOTONovember 10th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025