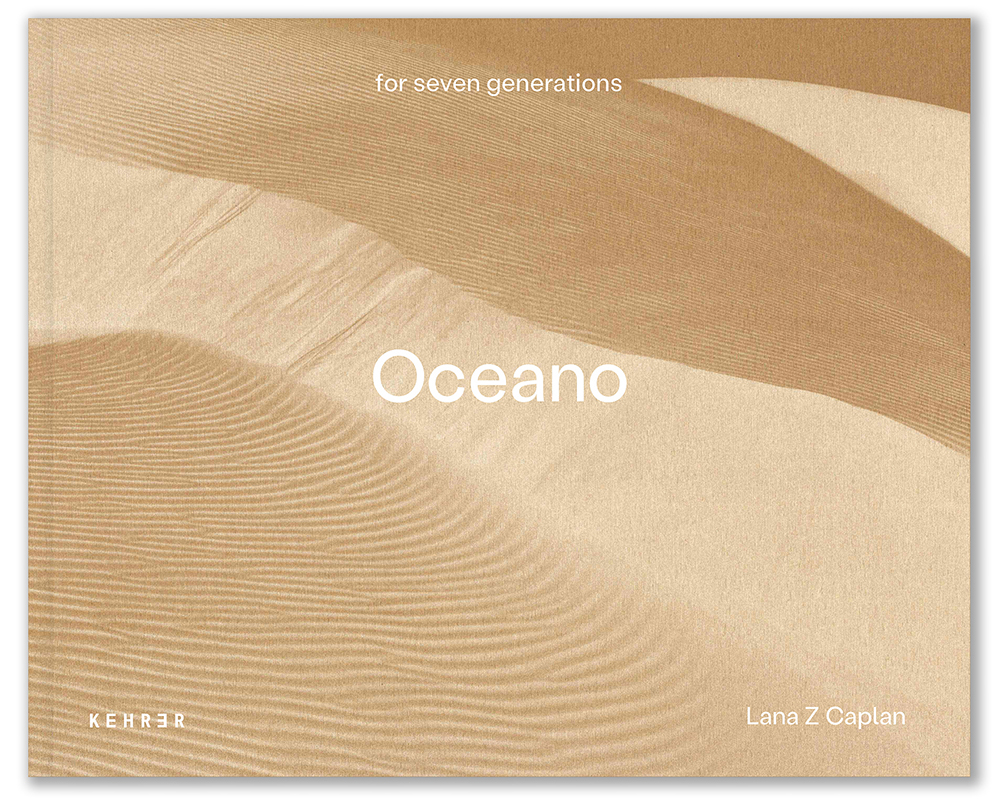

Lana Z Caplan: Oceano (for seven generations)

Through these stories, the book Oceano (for seven generations) offers both an interrogation of photographic conventions and a feminist response to landscape histories. Enlisting the past and present inhabitants as collaborators to enact performative and co-constructed moments, images confront historic approaches to portraiture (such as reductive stereotypes, typologies, fabricated tableaus, self-portraiture, and the vernacular). – Lana Z Caplan

Lana Z Caplan has recently released an important monograph, Oceano (for seven generations), the dunes of Edward Weston’s iconic photos and Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 buried movie set for The Ten Commandments, land that is home to the Dunites— the artists, poets, nudists, and mystics who lived in dune shacks from the 1920s to the 40s—hosts to Weston during shooting trips; and at the historical core, the native Chumash. These dunes now host a landscape of ATVs, inciting a decade-long legal battle with nearby residents over air quality.

Caplan attended Air Pollution Control District hearings, met with historians, scoured archives, and collaborated with yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash tribal leadership to excavate these histories in images. Ultimately, Oceano questions the legacies of colonization, photographic history, utopian ideology, and the future for the politically charged and environmentally threatened Oceano Dunes.

The subtitle for the book for seven generations comes from a phrase used by Lorie Lathrop-Laguna, ytt Northern Chumash Tribe, in a phone conversation with Caplan ― “Our decisions are made while thinking seven generations into the future“. The Seventh Generation Principle is believed to date back to the twelfth century Great Law of Peace of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

Tomorrow, June 21st, Caplan will be giving an in-person talk and doing a book signing from 6:30- 8pm, at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester, MA. To register, go here.

An interview with the artist follows.

©Lana Z Caplan, Arthur’s Boat, Oceano Depot, OceanoSpread from Oceano (for seven generations), published by Kehrer Verlag

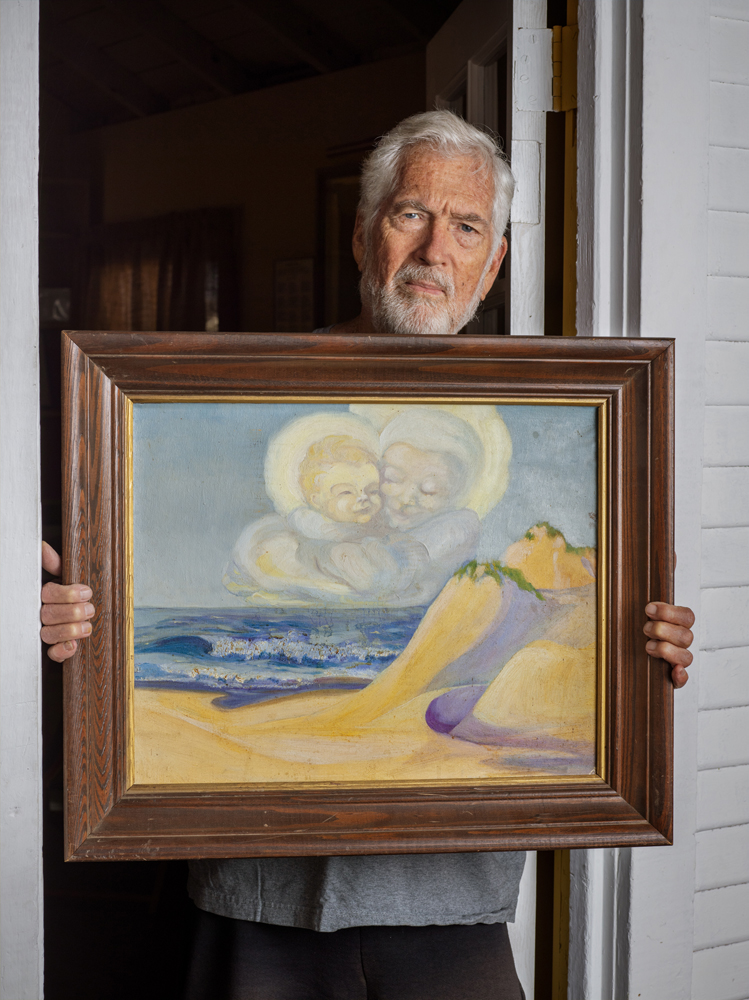

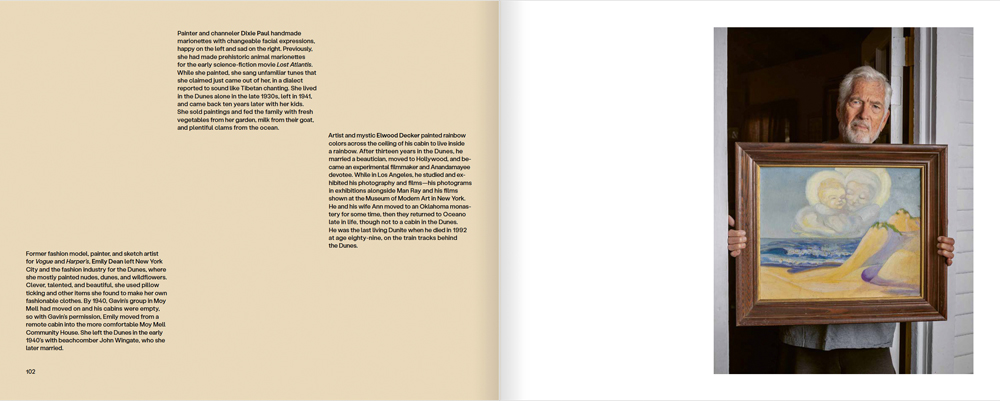

©Lana Z Caplan, Dunite Historian Norm Hammond Holding Painting by Dunite Dixie Paul in Gavin’s Cabin, Oceano, Spread from Oceano (for seven generations), published by Kehrer Verlag

Lana Z Caplan is a photographer and filmmaker. Her most recent project contrasts the subsequent inhabitants of California’s Oceano Dunes – Indigenous Chumash and depression-era artist and mystic squatters with the current ATV riding community, the source of a public health crisis. Her work has been featured in publications such as ARTnews, Hyperallergic.com, LA Times, Lenscratch.com and The Boston Globe, exhibited in museums such as Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson, Institute of Contemporary Art San Diego, Everson Museum of Art, Inside Out Art Museum Beijing, Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo Mexico City, National Gallery of Art Puerto Rico, Griffin Museum of Photography, and screened in numerous festivals around the world. She earned her BA and BS from Boston University, MFA in Photography from Massachusetts College of Art and is currently an Assistant Professor of Photography and Video at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, CA.

Follow on Instagram:@insta_lana_gram

Follow on Instagram: @kehrerverlag

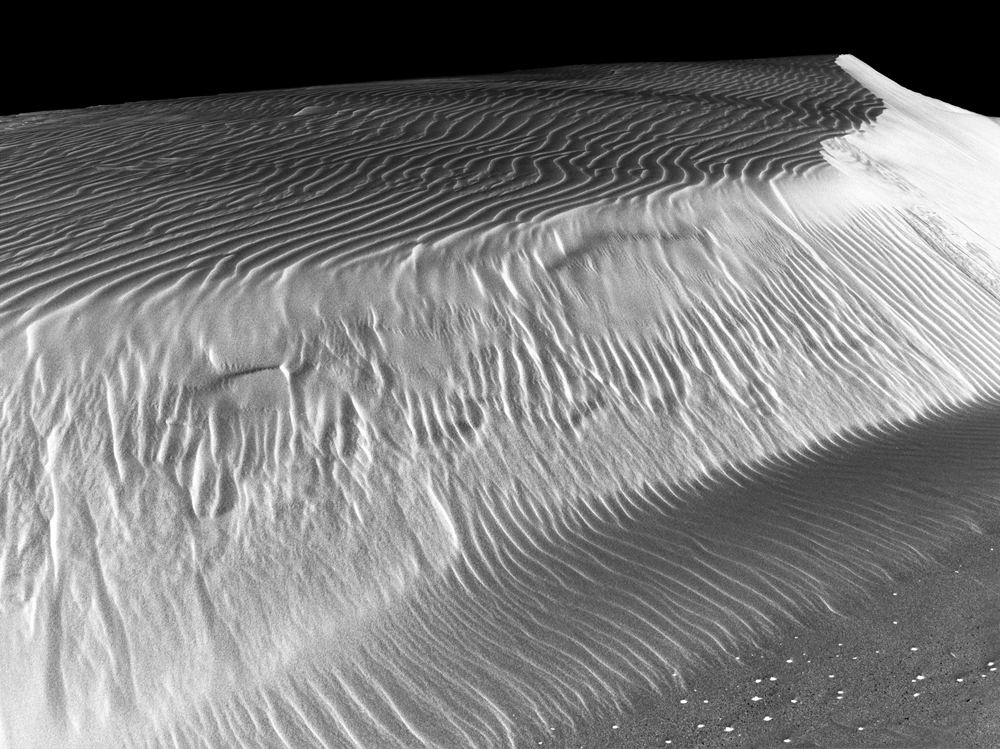

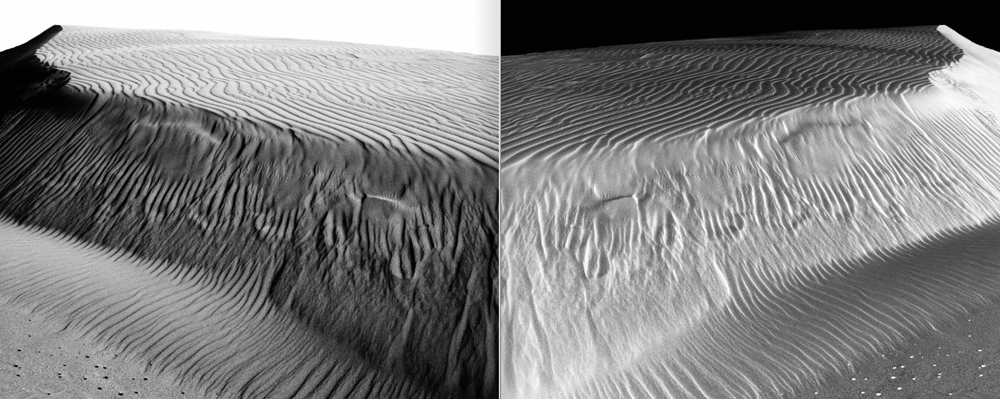

©Lana Z Caplan, Dunes 7, Oceano Dunes, Dunes 7, (negative), Oceano Dunes Spread from Oceano (for seven generations), published by Kehrer Verlag

Oceano (for seven generations)

Coming from Brooklyn, I had never lived anywhere like San Luis Obispo. It was 2016 and I settled for my new job in the café-lined university town center. Just outside the downtown, there were rolling hills with cattle and vineyards, Trump campaign signs in front yards, and lots of pick-up trucks in shopping plaza parking lots. On my first day of teaching, I found myself parked next to a field of sheep. I was unmoored. Seeking my footing, I set out to find a place where I had something to grasp – I discovered that the iconic dunes of Edward Weston’s photos were only 19 miles south of town and went to visit. What I found was startling – a frenzy of whizzing wheels, a cacophony of motors from ATV and off-road motorcycles, and a RV village along the beach which has incited a decade-long legal battle with nearby residents over air quality.

This was not the utopian, mythological, American West landscape I imagined. Of course, I knew the reality of the American West is not simply the carefully constructed images of the California Precisionists, the mythic emptiness of Timothy O’Sullivan’s survey images, or the hyper-masculine rugged terrain of Hollywood’s Westerns. Yet this is, more profoundly, a landscape of stolen territory, failed utopian ideals, exploited and extracted resources, homeless encampments, and destroyed habitat. These are the histories underneath the familiar tranquil dune images that all came to the surface for me.

My seven-year journey of researching, collaborating within the community of Oceano, working with yak titʸutʸu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribal leadership, and countless days on the sand, became a conceptual collection of stories from the Oceano Dunes. While these are the dunes of Edward Weston’s iconic photos, they are also the dunes of Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 buried movie set for The Ten Commandments; of the Dunites – the artists, poets, nudists, and mystics who lived in dune shacks from the 1920s to the 40s – hosts to Weston during shooting trips; and fundamentally, of the native Chumash.

Through these stories, the book Oceano (for seven generations) offers both an interrogation of photographic conventions and a feminist response to landscape histories. Enlisting the past and present inhabitants as collaborators to enact performative and co-constructed moments, images confront historic approaches to portraiture (such as reductive stereotypes, typologies, fabricated tableaus, self-portraiture, and the vernacular).

Assembling these images and texts together, with their range of styles, subjects, and goals, takes each type of image out of their context, undermining what would seem to be their individual intent, and constructs meaning through their relationships. And ultimately, the work’s dynamic historic context, as a locus of human interactions and values, intends to charge this cultural landscape with significance far beyond the Oceano Dunes.

Essays contributed to the book are by yak titʸutʸu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribal Chair Mona Tucker with her son Matthew D. Goldman, and Hanna Rose Shell, Associate Professor of Critical and Curatorial studies and Director of the Stan Brakhage Center for Media Arts in Boulder, Colorado.

From the text šumoqini by Mona Olivas Tucker and Matthew D. Goldman:

“I watch over special places and feel proud of my ancestors. Walking the Dunes can feel like heaven. On the nights when no one is there, it’s a sanctuary. This is a place that can help you heal from trauma and pain. Walking in the dunes, on the beach, or in the water is healing. I’ve seen people who are sick go there to recover. I’ve seen some people scream to the ocean. Healing can happen. During the times when the beach is flooded with people and vehicles, I feel sick and sad. Huge amounts of filthy trash is left behind in a place I love. Damage by vehicles is happening to the dunes, damage to animals, birds, plants, and beautiful flowers. Some won’t survive and won’t be seen again.“

From the text Vanishing and Morality in the Dunes by Hanna Rose Shell:

The Rancho Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes present a highly textured environment of cultural, aesthetic, and political possibility. Often called simply the Oceano Dunes, and covering eighteen miles of California’s Central Coast, they are governed by a complex of federal, state, local, private, and tribal land ownership and usage agreements. In her body of work, Lana Z Caplan explores the Dunes and finds layers of com- munities that have been alternately celebrated and erased; her project’s multiple narratives traverse space and time. Ruins (remains, remnants, relics, vestiges)—from broken headlights, to old movie props, to discarded clam shells—their concealment and their enshrinement, permeate the topographies and temporalities of the dunes.

American Flag, Oceano Dunes, State Vehicular Recreation Area, from Oceano published by Kehrer Verlag ©Lana Z Caplan

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography.

I grew up with a camera in my hand. My dad bought me a Polaroid when I was 4 and made sure I had subsequent cameras and film for my childhood through all iterations of point and shoots. He was always taking photos with his Nikon, which then became mine. Art was always a big part of my life. I took art classes and went to an art camp as a kid. For a time, we lived across the street from the Philadelphia Museum of Art and my time at the museum left a deep impression on me. However, we were not a family of artists by profession, other than some cousins that were commercial artists, so I didn’t really think much about photography in a rigorous way until much later. I was an Art History major in undergrad, and it was there that I discovered contemporary art photography. That was a real revelation. Still, it was several years before I realized photography could be what I did with my life, and then several more years to find a path to where I am now.

Blanca and Gabriela, Oceano Dunes, State Vehicular Recreation Area, from Oceano published by Kehrer Verlag ©Lana Z Caplan

Congratulations on the book, how did it come about?

I moved to San Luis Obispo for a teaching position in 2016. I had been living in Brooklyn and this move was quite a culture shock for me. San Luis Obispo is a beautiful place, yet totally the opposite from NY in every way. Instinctively, I sought out something familiar: the sand dunes that Edward Weston photographed were only 18 miles south of my new home. I was totally shocked to find an RV village on the beach and the off-road vehicles screaming over the Weston’s dunes.

In talking with a colleague, I learned about the Dunites. They were a unique community of free-thinking artists, writers, and mystics that lived in mainly salvaged wood shacks during the 1920’s – 40’s. They believed there was a creative and spiritual energy vortex at this spot. And of course, this landscape holds significance for Indigenous people who for centuries have known the pull of the place.

I then discovered an urgent public health crisis. The residents living adjacent to the dunes experience some of the worst air quality in the nation from dust created by ATVs grinding down the sand. They have been battling in the courts for almost two decades. At this point, the Air Pollution Control District tried to mitigate the dust with revegetation and small closures with little impact. This last piece is what kept me going – I felt that in addition to historic interest and quirky California stories, there is contemporary relevance here that expands beyond the dunes of Oceano.

From a conceptual and medium specific point of view, this place has it all. Every era of photographic history is embedded in the landscape and portraits possible here: the ethos of the Naturalists, Modernists, New Topographics, typological and ethnographic portraits, and contemporary cinematic tableaus. The blank, shifting sand was a like a tabala rasa to each successive group of inhabitants. And so too it could be a clean slate for the telling of each of the layers of this story, each using different photographic modalities, referencing the malleability of history through the lens of photography and media. It was that exploration which really guided how I connected this collection of stories.

Tell us about the research involved in the project.

This was a heavily researched project. More layers continually surfaced that I explored yet could not include. I spent time at the local libraries and the History Center in San Luis Obispo reading news clippings about the Dunites, the court proceedings that established the Guadalupe-Nipomo National Wildlife Refuge, and experiencing Indigenous Chumash culture and handicrafts. I found books about the Dunites, environmentalist Kathleen Goddard-Jones, and Cecil B. DeMille’s production of The Ten Commandments. I attended and streamed the Air Pollution Control District board hearings, which were held to try to find a way to mitigate the particulate matter that is coming from the riding to the neighboring communities.

I also tried to talk with people in the community involved in these issues and topics. This included the Tribal Chair for the yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini Northern Tribe, Mona Olivas Tucker and her family, members of Concerned Citizens for Clean Air, the staff and supporters of the Dune Center where Cecil B. DeMille’s sphinx is lives, Dunite historian Norm Hammond, environmentalist and “ecohooligan” Bill Deneen months before his passing at 93, and many people out riding in the dunes. I attended events like “Dunite Days” at the Oceano Depot, a screening of Peter Brosnan’s documentary The Lost City of Cecil B. DeMille, and several docent-led walks in the dunes.

I also researched Edward Weston’s time in the dunes through his images, his diaries and the writings of Charis Wilson, who accompanied him there. I like how this quote pulls together the Dunites and the photographs of Weston: “A hundred miles up the California coast at Oceano lay the dunes that Edward had first visited with Willard VanDyke in 1934. Gavin Arthur (a grandson of President Arthur) lived there, where he functioned as patron to a collection of artistically inclined dune dwellers who inhabited a cluster of cabins at the edge of the mountainous dunes that began near Pismo Beach and stretched south for twenty miles. Gavin had invited Edward to come back anytime and stay as long as he liked. Edward had been fascinated by the “made for photography” aspect of the place and was eager to spend a few days exploring it. “You won’t believe it,” he said. “Everything is black and white!” – Charis Wilson from the “Through Another Lens: My Years with Edward Weston”, Charis Wilson and Wendy Madar, 1998.

The dunes have such a profound historic legacy through photography and film, but you also share the less romantic side of dune culture. Did you grow to understand/appreciate the dune buggy culture?

There are over 1.5 million people visiting the riding area of the Dunes each year, so it is hard to categorize or make blanket statements about the culture. I met a lot of sweet people that were generous with their time and resources. I remember meeting a father who was teaching his son to fix a part on the motorcycle at sunset next to the campfire. He was beaming with pride at his pre-teen who was enjoying working on the bike with his dad. They were there for the weekend together making special memoires. I also met people that had radically different political views than I hold, and they were careful not to be aggressive or engage with me about polarizing topics. There is a feeling out there like you might experience at a concert of your favorite band or at a game with your sports team, where strangers embrace you because of the shared love for the band or team. However, there is a lawless vibe that is loud and full of litter and exhaust in black plumes of smoke. People are airlifted to hospitals after driving off 30-foot-high dunes on a regular basis. I can see how riding on the sand can be fun for some and could be done responsibly, but for me, it is not how I choose to spend time in nature.

Dust Circles, Oceano Dunes, State Vehicular Recreation Area, Oceano Dunes, from Oceano published by Kehrer Verlag ©Lana Z Caplan

When you moved West to accept a teaching position, what kind of work were you making? Were you already engaged with the landscape?

For many years I’ve been making photographs, films/videos, and installations. Before I moved to San Luis Obispo, I had been making more videos than anything for about five years, though always working on long-term photography projects. I continued making experimental videos while researching and shooting in Oceano. The subjects of these recent works are engaged with the landscape, taking up environmental and political themes and are always self-referential in regard to the medium. For example, Maelstroms (2015) uses animation, heat sensitive camera footage from US border patrol screens, military bombing drone monitors, and other collected footage, to form a mediation on the dehumanizing use of image technology. Patches of Snow in July (2017), made after Trump’s inauguration, uses images I made of the landscape of the volcano Haleakala on Maui as a backdrop. In the audio, mythology and religious fanaticism, climate deniers, environmental profiteers, and natural disasters are all reflected in the mirror of this morphing landscape, poised for new devastation. Canaries in the Mine (2015) directly references the climate crisis and the Anthropocene by creating an abstracted digital archive of a what is a disappearing natural world.

Throughout this time of making films, I was also still shooting a long-term photo project that investigates how social history can be evidenced through place. So far, I have photographed sites of public executions on three continents for this project. Of the places I photographed, China and the US are the only countries where capital punishment has not been abolished.

Orange Crush, Oceano Dunes, State Vehicular Recreation Area, from Oceano published by Kehrer Verlag ©Lana Z Caplan

Are you on to the next project or still focusing on this one?

Honestly, I am still deeply entrenched in this project doing talks, events for the book, planning exhibitions, and working on some related film projects. I feel like Oceano is just coming into its own now that I’m sharing it with the world. However, one new project that had to be started in the middle of everything with Oceano began with the birth of my daughter in 2021. Those photographs can’t wait so I’ve been shooting images about Motherhood, and we will see what happens with those in time!

What was your experience in creating the book?

As I got deeper into the research for Oceano, it became clear to me I would need to make a book to allow the images and texts to manifest the complex conversation. The project does have documentary elements but I see it as a conceptual artwork, realized in book form. Once I put things together in a mock-up, I realized what was missing and then I went back to shooting and collaborating.

Collaboration with members of the community was really important to me and allowed for another level of discovery. Mona Olivas Tucker, Chair of yak tityu tityu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribe, and I worked together to decide on how to include the contemporary presence of her Tribe in this place. I also asked the Tribe to contribute an essay to the book.

Dunite historian Norm Hammond and I spent many hours together talking and photographing to shape the Dunite presence. Among other things, Norm brought me boxes of Dunite artist and mystic Elwood Decker’s personal memories. After Elwood left the dunes in the late 1940’s, he moved to Hollywood, married a beautician to the stars, and became an experimental filmmaker and photographer. Norm shared news clippings from a show of his films at MoMA and a show of his photos with Man Ray, his sketchbooks, letters he wrote and received, and his personal family photos. From these materials, I used one of Elwood’s letters describing life in the dunes as a last word in the book.

For the main essay in the book, Hanna Rose Shell came to stay with me in SLO and we spent a few days touring. We had a blast. I took her out to the riding area and to the Dune Center to meet the Sphinx. We walked in the nature preserve area of the dunes with my almost 2-year-old and spent time at the Oceano Dunes visitor center where Mona’s family has a historical exhibition about the yak tityu tityu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribe. It was amazing to share all the things I was thinking about with her and have her insights shed new light.

And when the time came to put it all together, I was thrilled I was able to make this book with Kehrer Verlag. I was hoping to work with a publisher that would understand what I was looking to do, and they definitely got it. The designers and team had great suggestions and the whole process was fantastic. And I am particularly thrilled by the gold paper we used for the covers – sparkle you can’t really see in a digital image of the book.

Matthew Goldman, yak titʸutʸu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribe, Oceano Dunesfrom Oceano published by Kehrer Verlag ©Lana Z Caplan

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Linda Foard Roberts: LamentNovember 25th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025

-

Bootsy Holler: Making ItNovember 9th, 2025