Gary Owens: In the Room

Last winter, I discovered Gary Owens’ work on Instagram and was intrigued by his layered depictions that remind me of the starkness of early Hollywood films. Upon reading his statement, I learned that he creates these sculptural collages using images from antique magazines and artificial intelligence. While many photographers have dismissed the potential of A.I., I’ve always believed someone would do something remarkable with it. I admire artists who challenge the boundaries of photography, and Gary Owens is one of them. By using A.I. and other methods to collage images and then reshooting them with a pinhole camera, he ultimately transforms them back into photographs.

Gary Owens is an artist and art lecturer based in the Northwest of England who works primarily with film photography, digital collage and montage.

Follow Gary Owens on Instagram: @owensphoto

My work has been pretty broad over the years, incorporating photography, digital montage, collage, assemblage, bookmaking, animation, sculpture, installation and creative writing. Recently I have had two major approaches, creating digital montages from vintage magazine images, and working with pinhole cameras. My work often returns to similar themes around loneliness, isolation and an inability to communicate, and I’m always looking to my work for some way of processing who I am and what I should be doing. I am an art teacher and that takes up a great deal of my time and creative energy, so I don’t consider myself to have an art career as such, but I have been trying to find ways to get my work out to a wider audience through online open calls, competitions and themed exhibitions.

GB: Tell us a little bit about your childhood and how you became an artist?

GO: I grew up, and still live, in a town called Skelmersdale in the Northwest of England. The first means of creative expression that gripped me was writing poetry when I was a teenager, but for my 21st birthday my parents bought me a Zenith SLR camera and photography quickly became a passion. After completing an English degree I returned to education to become an art student, and then an art teacher. I have taught photography and all other forms of art at West Lancashire College for the last 28 years.

GB: Talk about how collage became your method of working and how that process has evolved?

GO: Sometimes I describe collage as the last refuge of the scoundrel, it’s certainly a method I’ve taught to students of all ages and abilities over the years because it is so immediate and everyone can produce an outcome they can be pleased with. I was always interested in breaking up the surface of the standard photograph, to some extent ‘straight’ photography leaves me dissatisfied. Using collage and montage in all forms was just one way of adding depth and playfulness to my work. When I started using Adobe Photoshop, 20 or so years ago, that process became more digital than physical. I produce a lot of digital montages using vintage materials from magazines, my particular favourites are the ones published during Hollywood’s Golden Years from the 1920s to 1940s.

GB: Discuss the series “In the Room.”

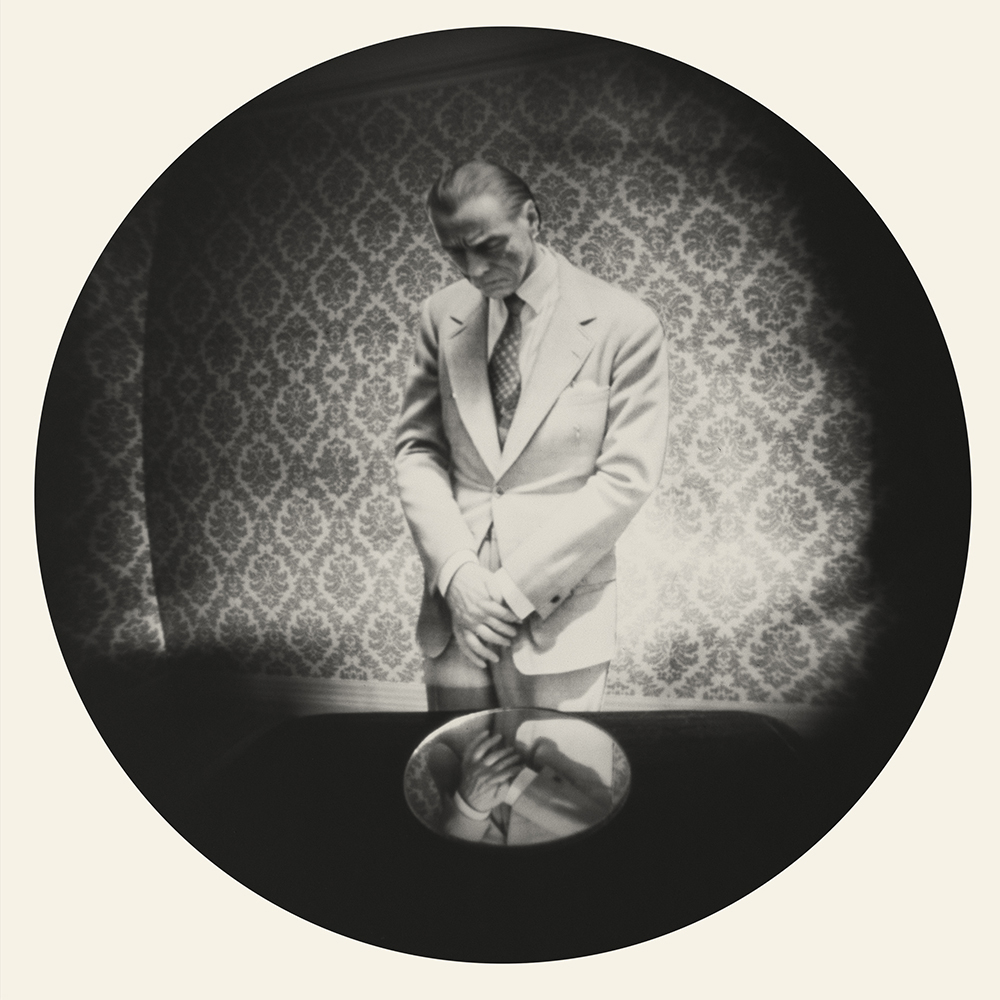

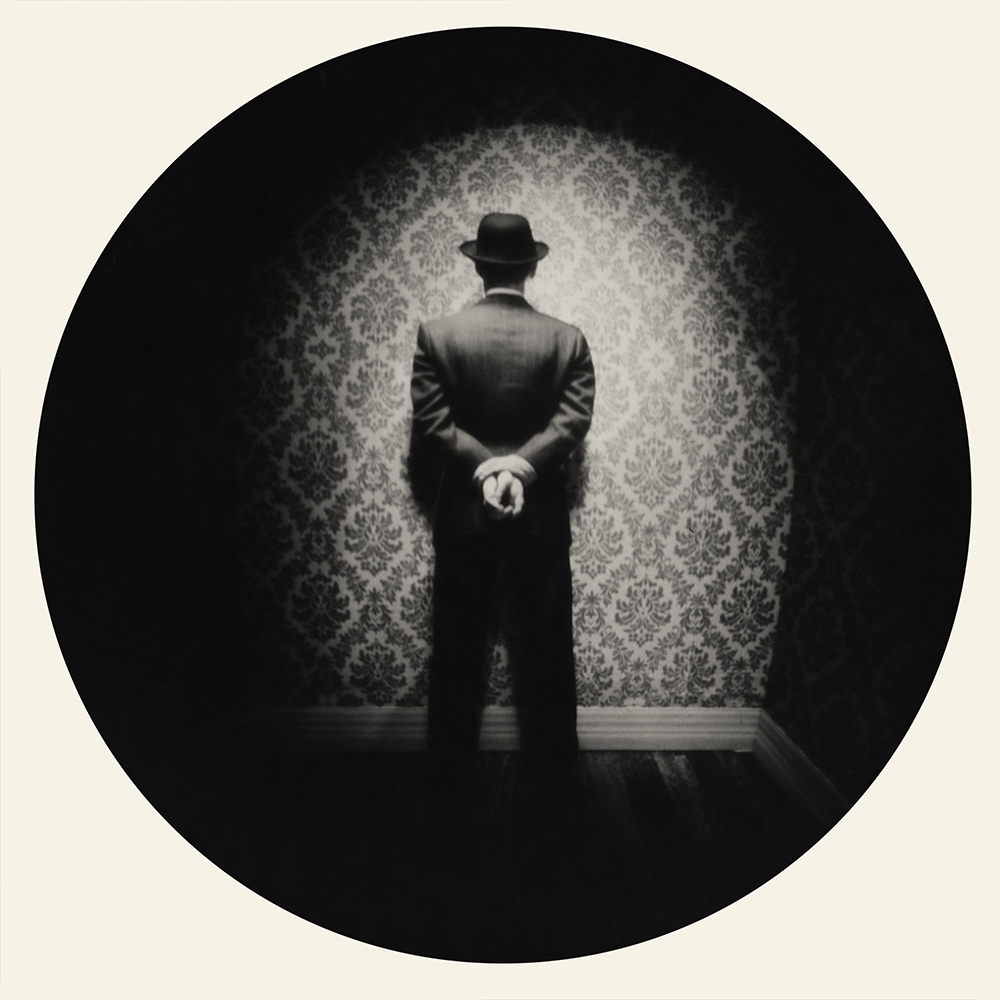

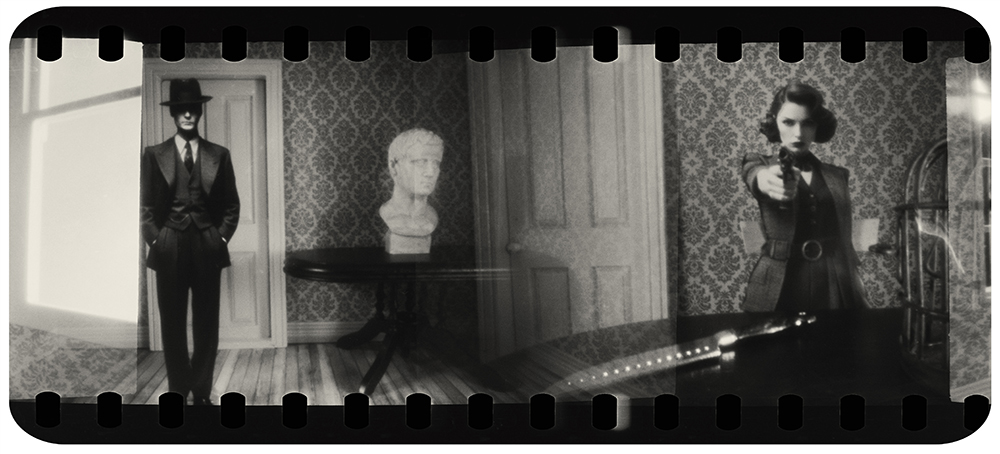

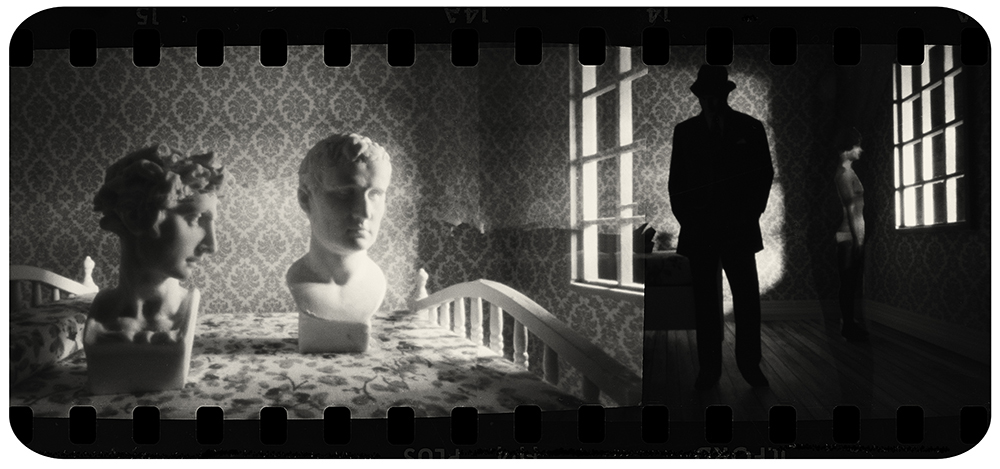

GO: I think that essentially grew out of the pandemic, and the two lockdowns we had in the UK. I live in a first-floor apartment with no access to outdoor space, and we were instructed to stay indoors at least 23 hours a day during lockdown, so I started thinking about what table-top photography I could do. That morphed into my returning to a love of mine, pinhole photography, and making pinhole cameras. I made about 50 cameras during the lockdowns and started to use them to photograph card figures in doll’s house sets. At the time I was just making images but afterwards I realized that the work was about claustrophobia and projecting meaning onto figures in confined spaces. The room becomes the world.

GB: Describe your process, I know you use several methods including Artificial Intelligence. What makes that brilliant to me is that the imagery returns to a photograph.

GO: Yes, originally, I was using the same figures that I used in my digital montages. They came from vintage Hollywood magazines and also from family albums from the early part of the 20th century, which I collect. I prefer everyone in my images to be dead. When AI started to get traction on the news, I thought I’d better look into it, because I reckoned it was only a matter of time before my students started using it and I’d be out of my depth. I was immediately intrigued by the text to image generators, such as Leonardo, and realized it could be a way of creating figures to use in my sets. That completely changed the series in a way. Searching for useful images through thousands of magazine pages and then creating work out of what you find is very different to writing text prompts. That ‘shifts’ the idea generation process forwards in time, you need an idea before you write the prompt. It was also a lot less time-consuming. I print and cutout the figures, compose with them in a physical set, and then photograph the result. I photograph in two ways – mostly through using pinhole cameras I have made from tobacco tins, and shooting onto photographic paper, or for the panoramic images I have used a Lerouge pinhole camera shooting on 35mm black and white film. Once I have negatives, I digitize them and work through to the final image in Photoshop, usually just inverting, spotting, cropping and tinting.

GB: Is the black and white imagery inspired by film noir, with its wide angles, shadowy figures, and concerned poses?

GO: Yes it is, the most inspirational book I remember as child was a massive history of MGM movies that someone bought my father, it was full of thousands of incredible quality black and white film stills. I used to love to look at a still and wonder what the story was, to try and read the relationships between the figures and the mood of the scene. The style of film noir was always so dramatic, they were pushing the equipment they had to its limit, shooting indoors using portable lighting for the first time, experimenting with lenses and camera angles. Some of those cinematographers were amongst the greatest cinema has ever known, in my opinion. The stills photographers too, who usually went uncredited, were masters of their craft.

GB: Looking at your website, I think you can see the evolution and range of your collages, where does it go next?

GO: I honestly don’t know! I find it hard to work consistently during the academic year, because, as any teacher will tell you, teaching isn’t a job it’s a lifestyle. I have five weeks off during the summer and the more I think about how I’ll use them the more I start to panic, so the lesson I need to learn is to stop thinking about it. I genuinely believe that if you say what it is you are planning to do next that puts it into a form that will dominate and ruin your future creative decision-making processes. I think everything should be a surprise to the artist. Sometimes the surprise might be that the work could turn out to be trash, but if there’s no surprise, it is trash. For me that struggle between control and lack of control is at the heart of making art.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025

-

Mary Pat Reeve: Illuminating the NightDecember 1st, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025