Alice Wingwall: A Photographer who happens to be Blind

Every time I attend photo L.A., I am drawn into the Blind Photographers booth. It is filled with imagery that is a bit different, and that difference is what makes the work so interesting. Alice Wingwall is a regular exhibitor and today I am featuring some of her photographic work and her essays. Her photographic work is featured in the exhibition Sight Unseen, mounted by the California Museum of Photography in Riverside and now touring various cities internationally, including Washington D.C. and Mexico City and was also a part of the show Blind at the Museum, organized by the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

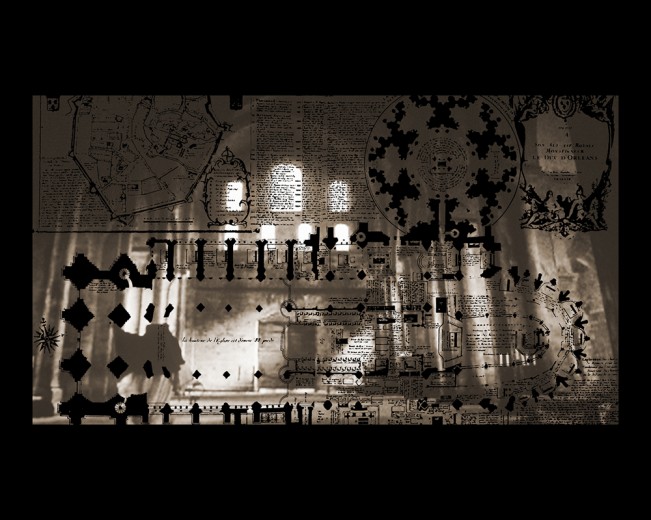

Alice works with the juxtaposition of images. In her photographs, photomurals, sculpture, site-specific installations and film, she brings together compositional elements, memories and associations. The spatial arrangements, evocative prints and words that she creates have a very distinctive presence.

Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, Alice studied art at Indiana University, architectural history and sculpture at the University of California, Berkeley, where she was awarded an MFA and served as a graduate student instructor. She also studied in Paris at the Ecole du Louvre, the Ecole Metiers d’Art (stained glass studio), and the Atelier del Debbio for stone carving. With a grant from the Danish government she studied architectural history at the Royal Academy of Art in Copenhagen.

Subsequently she taught in the University of Oregon Honors College and started the sculpture program at Wellesley College as an Assistant Professor. Her work is included on the campus and in the collections of the University of Oregon, the Oakland Art Museum, the University of California College of Environmental Design, and in private collections in Massachusetts, Indiana, Texas, Oregon and California.

The film “Miss Blindsight: the Wingwall Auditions,” which she and Wendy Snyder MacNeil co-edited, also showed in many places, including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, where it was premiered as the Best Independent Film of the Year 2000 at the New England Film and Video Festival. The film provides insights into the changing life of an artist with degenerative retinal disease and is available on DVD.

Position paper, or positioning papers, or sort of

subversive photography

First position

83 percent of sight gone. Slivers around the retinal wall still accept and pass light rays and dusky images to the optic nerve. I lovingly caress my cameras. I think that the lens is better than my eye, but I mean that the film itself is perfect, that is, much more perfect than my damaged retina, my much deteriorated back eye wall, which cannot be moved along to a fresh working piece along a spool. There is nothing wrong with the front of my eye, it looks good. Too bad I cannot go out and buy a cassette of retinal wall. Well, I will get a wide angle lens instead. I will set it at f8 and almost everything will be in focus, the way the old Speed Graphics were, held over the heads in crowds. Technology will allow me to keep photographing, that is, high resolution film, in-camera metering. I will keep on, with my training in visual media and my ten years experience, photographing and printing. My sweet darkroom is only five years old. It has a kind of color spectrum lamp hanging from the ceiling, casting a pale peach glow from the top of the room. Yum.

Second position

In the cup-half-full mode, I say that I still have 10 percent of my retinal slivers, much slimmer, but functioning in those narrow lines. I make two great decisions. I get my first auto focus camera, one of the Canon EOS family. I sign up for guide dog school and graduate with Joseph, my angel dog, my saint and super photo model. I introduce him to all the buildings I love and have already photographed. Now he gets in many of the building shots. In a way, they become his starter palace dog house, his palatial pup tent. A changed kind of independence has emerged with this auto focusing and this dog direction. Dynamic duo work habits just ignore the beginning questions, “how can you photograph when you cannot see?” Well, there are training, experience, memory and insight.

Third position

5 percent full, this now narrow crystal cylinder. Auto focus is splendid in the camera. But there is no auto focus enlarger, and no auto measure for the developing chemicals. I am directed to Eddie, a wonderful black and white printer in San Francisco. We talk about composition and contrast, velvety blacks and tonal ranges. He saves one gorgeous barn image, taken with a red filter, but underexposed. That was a total bitch to print, he says, so do not do that again. Think about your exposure. I was using an old Hasselblad with no meter, and I guessed wrong. I gave up my darkroom and sold the equipment to another photographer. A major move – accepting sight loss and change, but not accepting not photographing. No way, not with the ideas and images that are in this brain of mine. And I cannot stop holding and hugging my several cameras.

Home is Where the Heart Goes

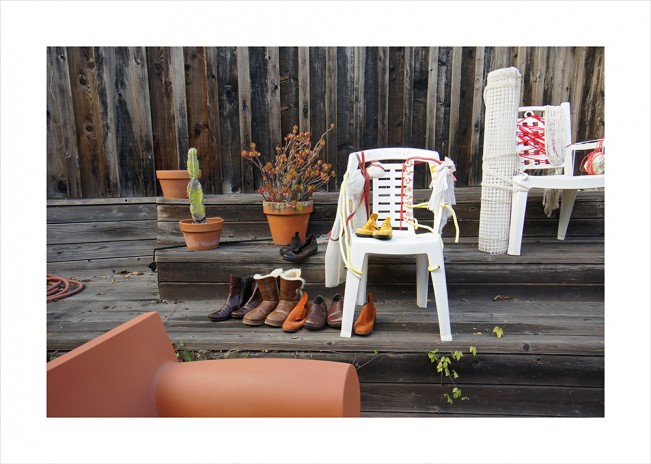

I stand just inside the very tall windows of the mill room, grasping the long handle of the right glass panel to open the window. The roar of the river rapids rushes in, and at least one handful of words falls forward over the sill, down toward the rapids, falling among the boulders. The words are all French, falling from my mouth as I gasped at the plunging of the water. I tried to catch some words, to return them to my mouth and ears, like grabbing for potato chips. Water, and the sound of its falling, had surrounded my working, and sleeping and eating for a total of eight weeks over six years. In my workroom, in the lower barn, words hovered, even in the silence of wrapping and coloring and drawing. Letters paraded silently on upper beams and ledges, whispering together to form words, sometimes huddled over my shoulders, sometimes curling around these shoulders to listen to what I was writing, one letter after another, on the seat of one chair or another.

Laundry tubs and a toilet lined one wall of the barn workroom, and tool storage and supplies covered one more wall beyond my large work table where rolls of cord, cloth, plastic garden ground covers and cuttings tools littered the surface. Around this table stood several plastic chairs, filled with linen rope, rocks and letters, waiting for my transformations to them. And the words whispering and parading and dancing their shapes into sounds through the room shaped the room as much as did the walls and laundry tubs. Yes, sounds and the sound of language had made this barn workspace mine. The sound of words and the sound of rushing waters encircled my imagining and my formations.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026