Korea Week: Jung, Kang

A huge thank you to Guest Editor and photographer Hye-Ryoung Min who shared the work of Korean photographers this week. Today ends the series.

Kang Jung has studied photography both in Korea and in the U.S., receiving a BFA from Chung-Ang University, Korea, an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts and an MFA from The School of Art Institute of Chicago. She has exhibited widely in Korea, China, and the U.S. and has received numerous Artist Fellowships. We are featuring three projects, each examining a different perspective of portraiture.

Kang Jung has studied photography both in Korea and in the U.S., receiving a BFA from Chung-Ang University, Korea, an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts and an MFA from The School of Art Institute of Chicago. She has exhibited widely in Korea, China, and the U.S. and has received numerous Artist Fellowships. We are featuring three projects, each examining a different perspective of portraiture.

Finding the Lost Face

By Sunyoung Lee

Jung Kang has been actively showing her photography works that often portray representations of subjects that are commonly depicted in the world of both the fine arts and photography. In Face, Face, Face!, the title of her current exhibition, Jung searches what seems most obviously present yet incomprehensible. Her current exhibition has two parts: The Portrait without a Face and Looking at Yourself. In The Portrait without a Face, Jung presents the paradoxical photographs of portraits in which the faces of main characters that should have been, according to conventional practices, placed in the center of the picture, are expelled off the frame. In Looking at Yourself, through an integrated medium of video and photography, Jung encourages her main characters to seek their own reality through asking questions and finding answers by looking at their own images. In the beginning of the history of photography, taking portraits, which was the main purpose of photography at the time, was rather ritualistic. Now people often take pictures and easily discard them; it has become such a common and convenient activity that most portrait photographs are not considered to be artistic representations. Since the ancient times, the human figure has been considered to resemble God’s, but this happy analogical connection to divinity has been disconnected in this modern time. A face in a small picture frame can have multiple meanings, but now the face lost its depth and became rather flat and superficial.

In the digital era in which the act of taking photography has become instant, easy and recreational, we treat other peoples’ faces as well as our own face in a “way too cool” manner. It would be no exaggeration to say that modern people carry a few handy masks in the format of ‘emoticons’ to express their momentous emotional status. Nevertheless, Jung still considers the human’s face important, though not in the same way faces used to be regarded in the early days of photography. Jung tries to present the other side of the human in an era of simulation in which the reproduction of self has become more important than the actual self. Jung smoothly conducts her study through an elaborate arrangement of modern digital devices. As Walter Benjamin’s aura of “the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction” has been faded into the past, we, the people of the digital era, still preserve the aura of nostalgia of portraits instantly produced after a quick act of spatial-temporal fixation. Modern portrait photography can be interpreted as an essential activity as humans are social beings, collaborating with and competing against their own tribe, thus, they probably cannot ignore to observe other people’s images.

Jung intends to avoid all the mythology involving statistical abstraction and so-called unique individuality. Through reflective devices and language, her main subjects enter into a communication system with their tools of imagination and symbol. As the modern psychologist Lacan predicted, reality cannot be entirely met by reality automatically. Except the cases of mystical connection or lucky coincidence, there is no exception. The self behind the world of imagination and symbols is watching for the opportunity to spurt out through the gaps. This is one of the reasons why the mirror of various layers were arranged to meet the individual self in Jung’s work. As one’s own recorded voice often sounds unfamiliar, the reflection of oneself on a mirror, especially on an electronic mirror like a monitor, might seem unfamiliar. This could be because the time difference exists in the reflections even though they were taken almost in the real-time. It is that difference that cannot be visually measured but clearly exists. The photographs of Jung’s experiment reveal that the angles between the interviewees’ seat and the monitor vary. The little differences in the angles could induce completely different self-impression. The time difference recorded by the devices in the experiment corresponds to the difference between the reflection on a mirror and the verbal reproduction.

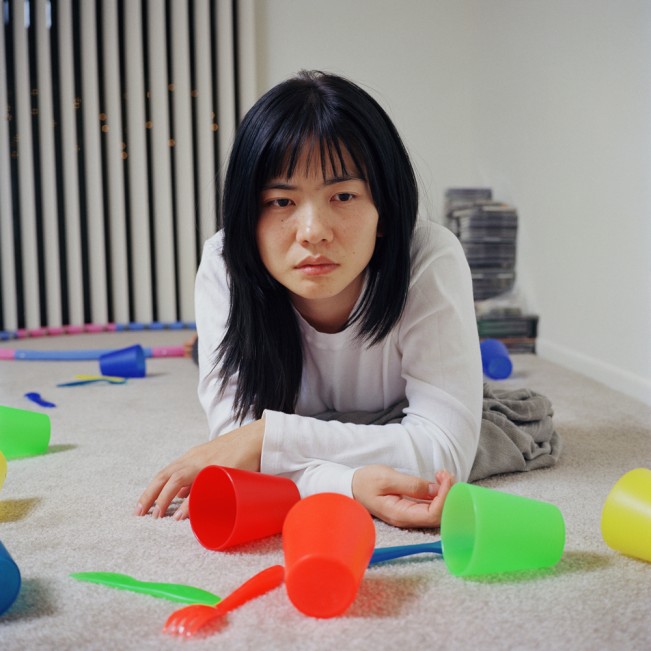

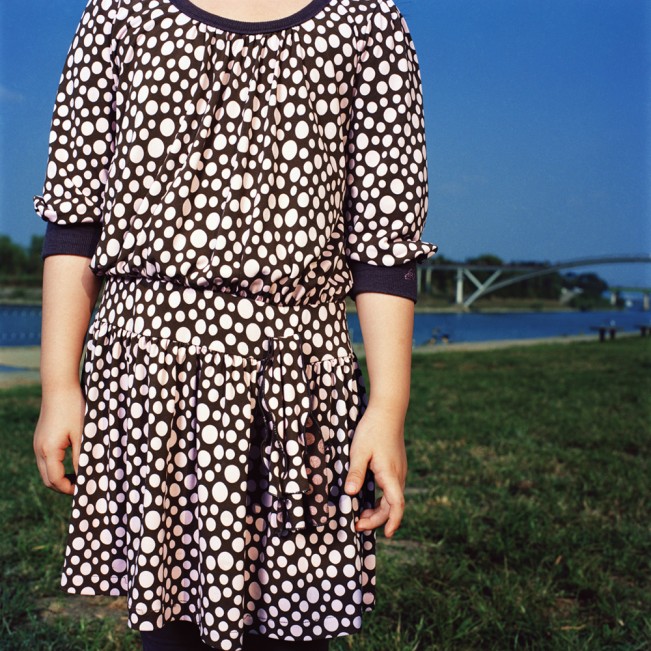

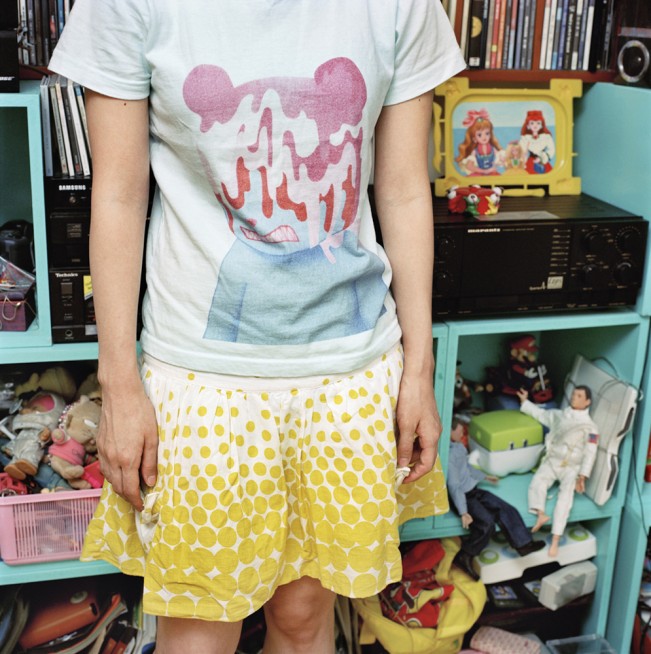

Portraits without a Face

It often seems only a matter of time until humans become objectified and codified. It has already become difficult to imagine a person as a completely code-free being. The more photographs become common and widespread, the harder it has become to understand humans. As Susan Sontag discussed in her On Photography, even assuming photographs provide a sort of understanding, the fact that the photographs do not concretely say anything is probably a more intriguing point. In the Portraits without a Face, Jung photographed her characters without a face in the frames. When faces, which have become so ordinary, are taken out of the frames, what remains in sight? Once severely expelling the faces off the frame, Jung focuses on the remaining details that consist of her characters. The twelve photographs in the Portraits without a face show peripheral parts of people who would have easily seemed ordinary if their faces were included. A square photograph of 1 by 1 meters (40 x 40 inches) focuses on the person by cutting its width and reducing the background. Through the details of indoor or outdoor backgrounds, clothing, skin complexion and props, one can predict the person’s gender, age, social status, etc. However, these characters are not typically classified as a poor old woman, a sophisticated urban woman or a housewife. Each photograph broadly represents a person rather than a person of a specific social or cultural role.

The audience of Jung’s work can learn more about the portrayed characters without their faces than typical portraits with faces. In the Portraits without a Face, the face is hidden and conceptually put in brackets but not in a disruptive way. These photographs offer a pleasure in discovering the portrayed person’s trivial tastes, the arrangements of the unique objects in the background accidentally caught, things that were to be easily ignored if his or her face were present.

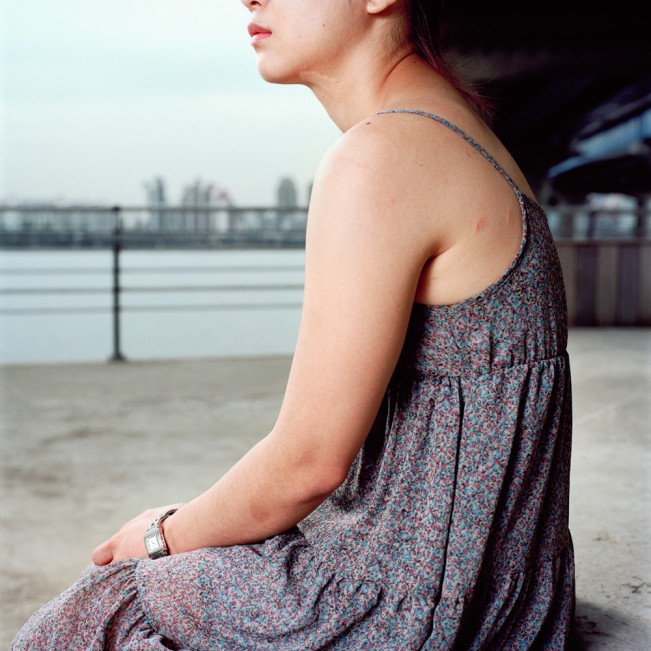

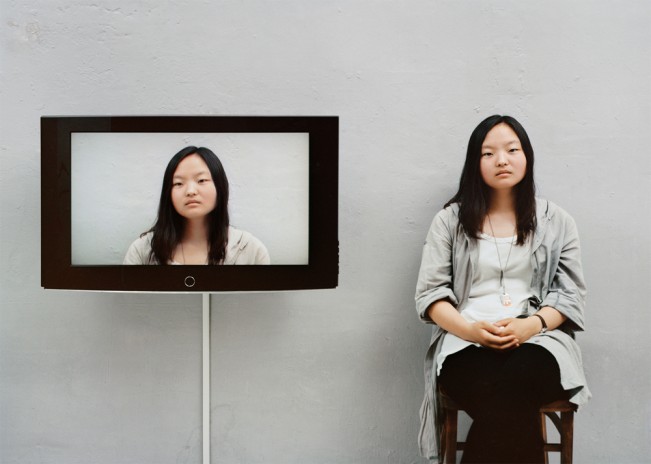

Looking at Yourself

The interviewing process in Looking at Yourself involves a different feedback from ones from monologues in a dark place, typical conversations in public or private spaces or other typical dialogues, even though they were voluntary interviewees and the artist may have tried her best to create a comforting atmosphere. Neither did the process involve a peculiar device to intentionally torture the interviewees. But these days it is a typical way to reproduce/reflect a human. Whether through an analogue or digital mechanism, people can see their own figure only through a reflection and they must interact with their reflected-selves. The self-representations of the interviewees are refracted thought their images on an electronic mirror (monitor) or their own words they hear through the devices around them. The results of the interviews varied in terms of interviewees’ age, gender and job, but it was consistent that there were not many who perceive themselves as coherent and logical beings. The Looking at Yourself project recruited the volunteers through an online posting, a method different from a typological sampling. This project also produces a result that is different from a natural approach prevalent in the pre-digital era where one casually took a picture of someone that portrayed his or her natural personality and mood.

Looking at Yourself consists of video works that ask questions about self-image. These video pieces were also presented as six large photographs exhibited on the first floor. This work utilizes the unique aspect of the photography medium as a mirror reflecting the portrayed characters. Twenty eight people were invited to sit and answer a few questions on their photographed images for about thirty minutes in a space where video cameras, digital photo cameras, mirrors and monitors were dynamically arranged. The typical six or seven questions of the interview were: “How do you see yourself? What is the difference between your image viewed by yourself and others? What differences do you see between your figure when you look in the mirror, and when you look in the monitor?” and so on. It is assumed that there could have been substantial psychological pressure on the interviewees in answering questions and simultaneously looking at their own image both on the mirror and monitor.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025