Will Wilson: The States Project: New Mexico

I had heard of Will Wilson’s innovative work in wet plate for many years in Santa Fe before I met him personally. It’s funny that you can live in the same town as someone, know and appreciate their work, but not recognize them if you run into them on the street. It finally took a mutual friend and perfect timing to be introduced to Will on the day I decided to spotlight him in our State’s project.

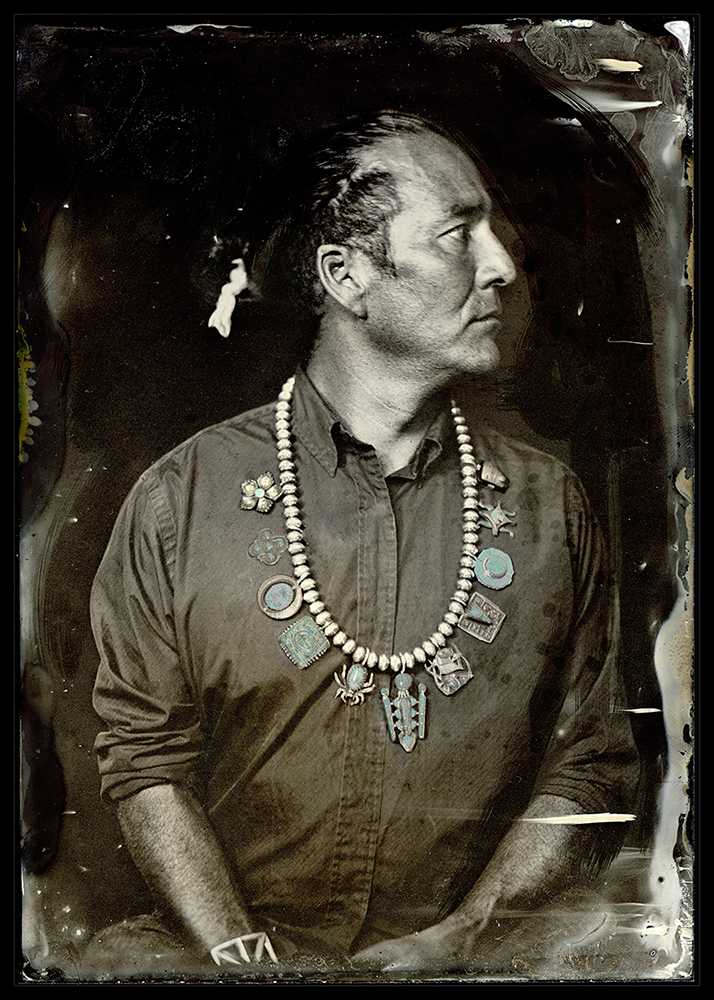

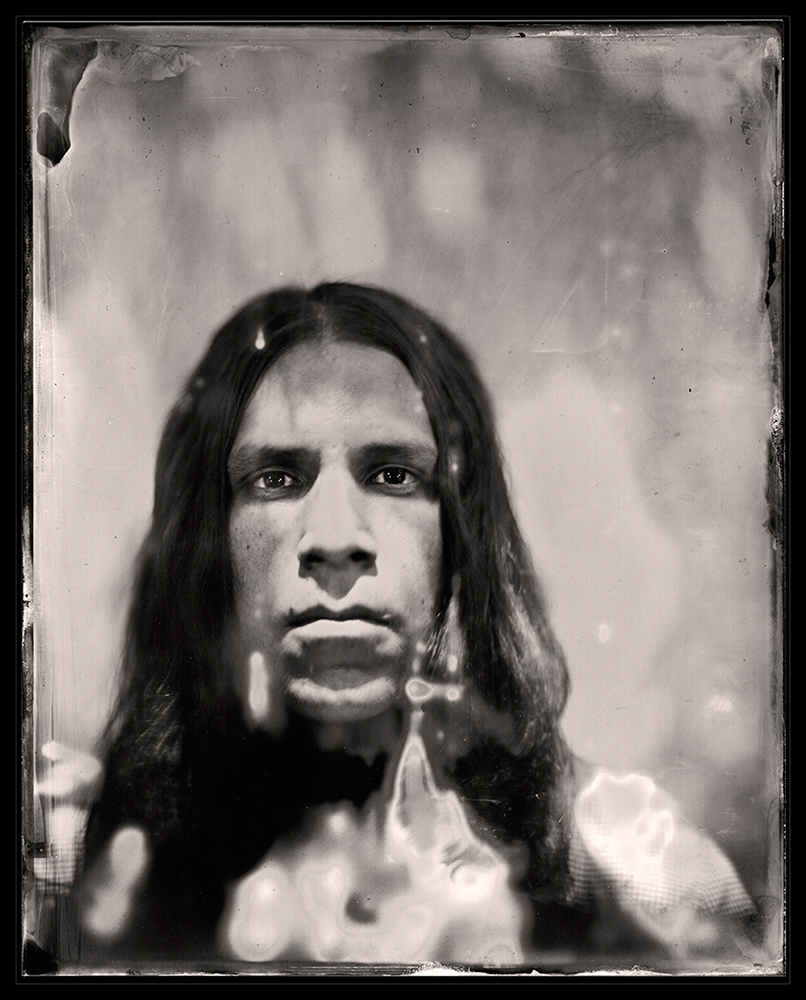

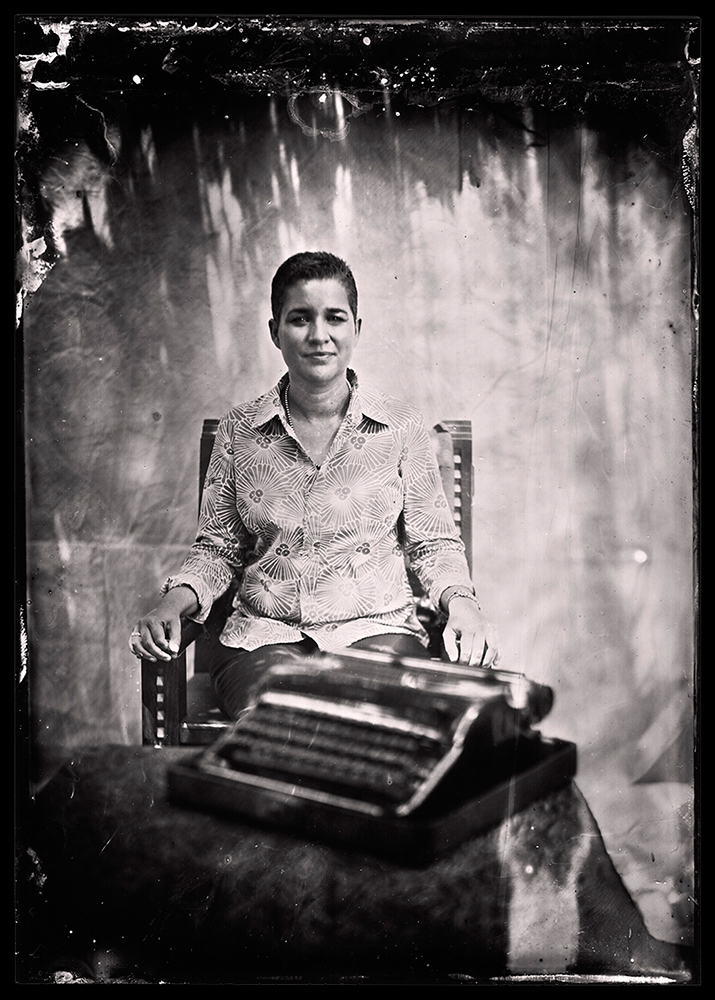

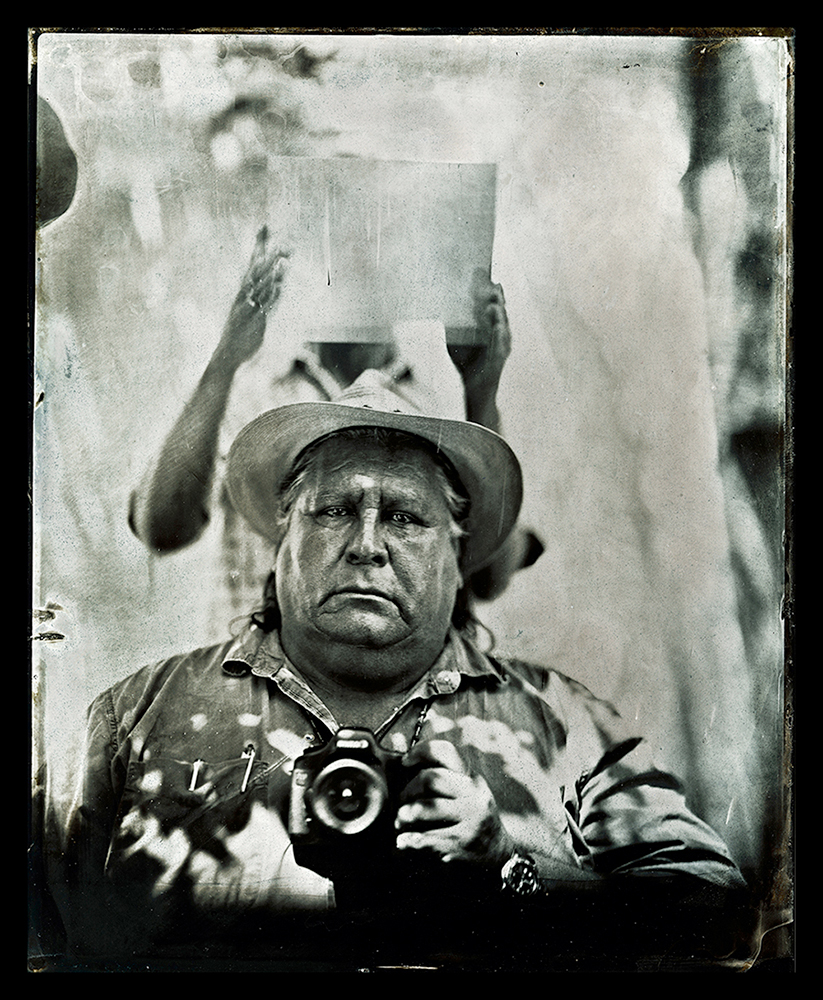

Will Wilson is a Navajo artist based in Santa Fe, and in 2014 was appointed the Head of the Photography program at the Santa Fe Community College. He was also formerly an instructor at the Institute of American Indian Arts. I am very excited about the work we are presenting here, Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange, which he began while at the Santa Fe School of American Research, and depicts contemporary Native artists and art professionals via the 19th century wet plate photographic process.

Toward a Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange

As an indigenous artist working in the 21st century, employing media that range from historical photographic processes to the randomization and projection of complex visual systems within virtual environments, I am impatient with the way that American culture remains enamored of one particular moment in a photographic exchange between Euro-American and Aboriginal American societies: the decades from 1907 to 1930 when photographer Edward S. Curtis produced his magisterial opus The North American Indian.[1] For many people even today, Native people remain frozen in time in Curtis photos. Other Native artists have produced photographic responses to Curtis’s oeuvre, usually using humor as a catalyst to melt the lacquered romanticism of these stereotypical portraits.[2] I seek to do something different. I intend to resume the documentary mission of Curtis from the standpoint of a 21st century indigenous, trans-customary, cultural practitioner. I want to supplant Curtis’s Settler gaze and the remarkable body of ethnographic material he compiled with a contemporary vision of Native North America.

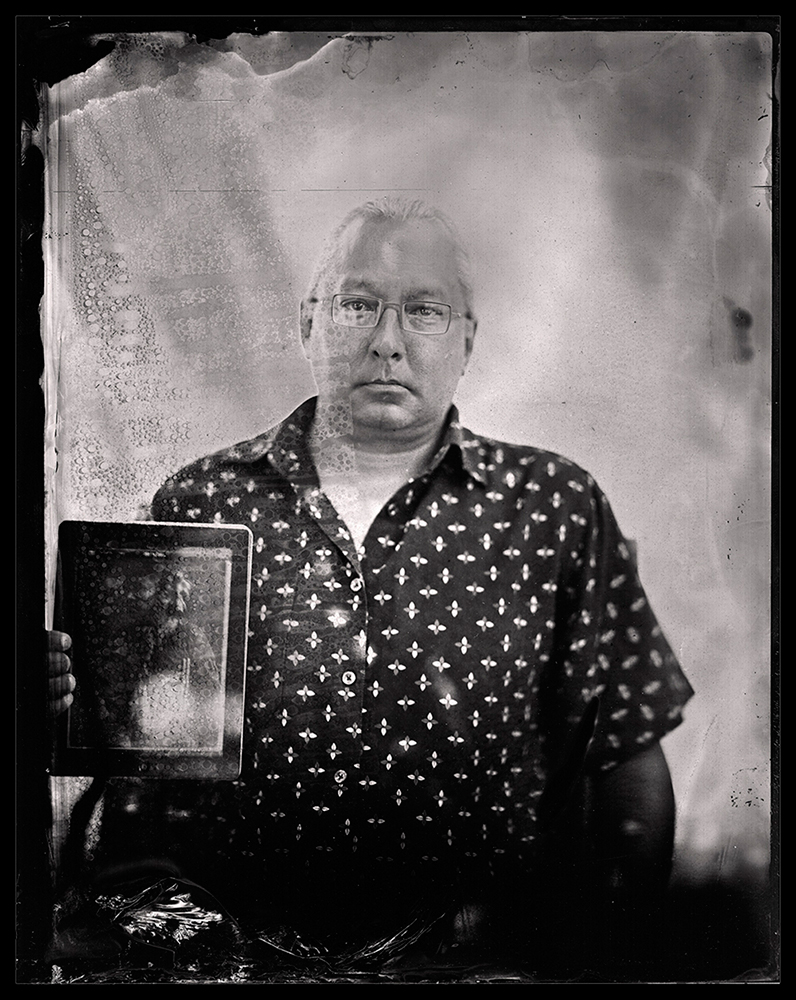

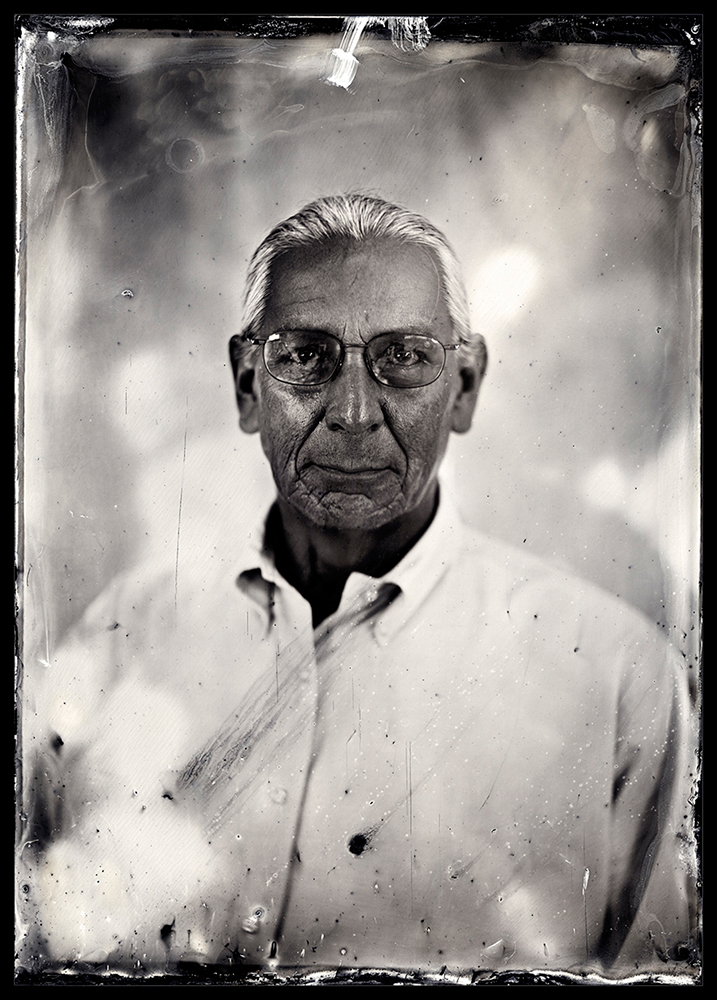

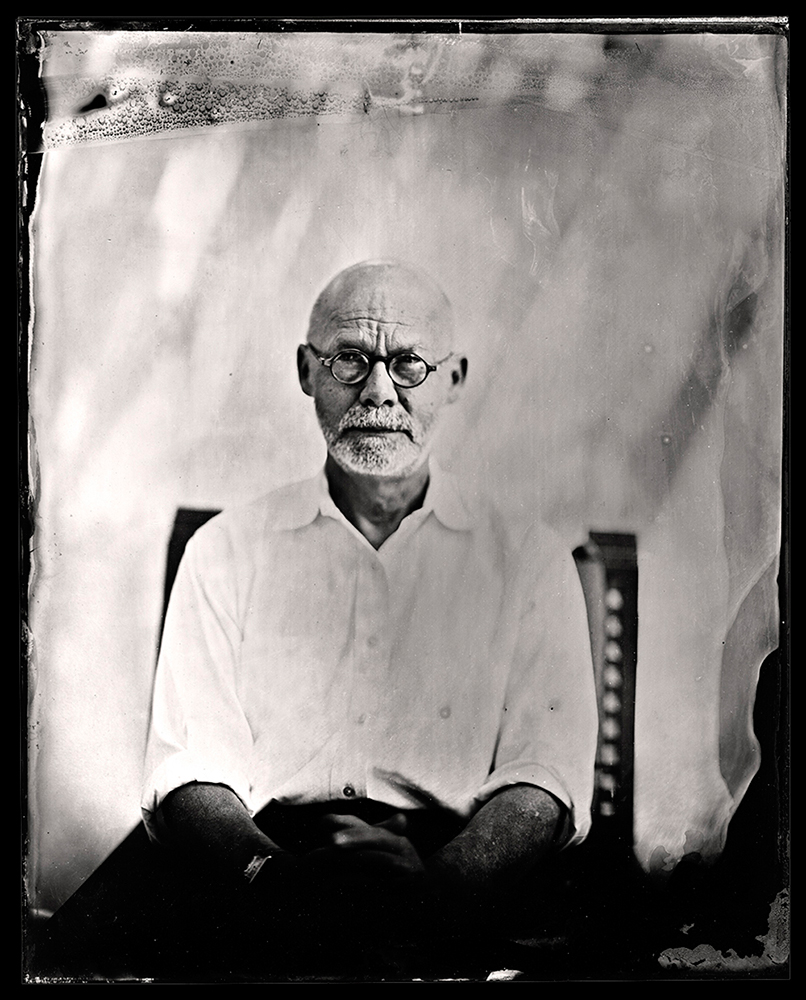

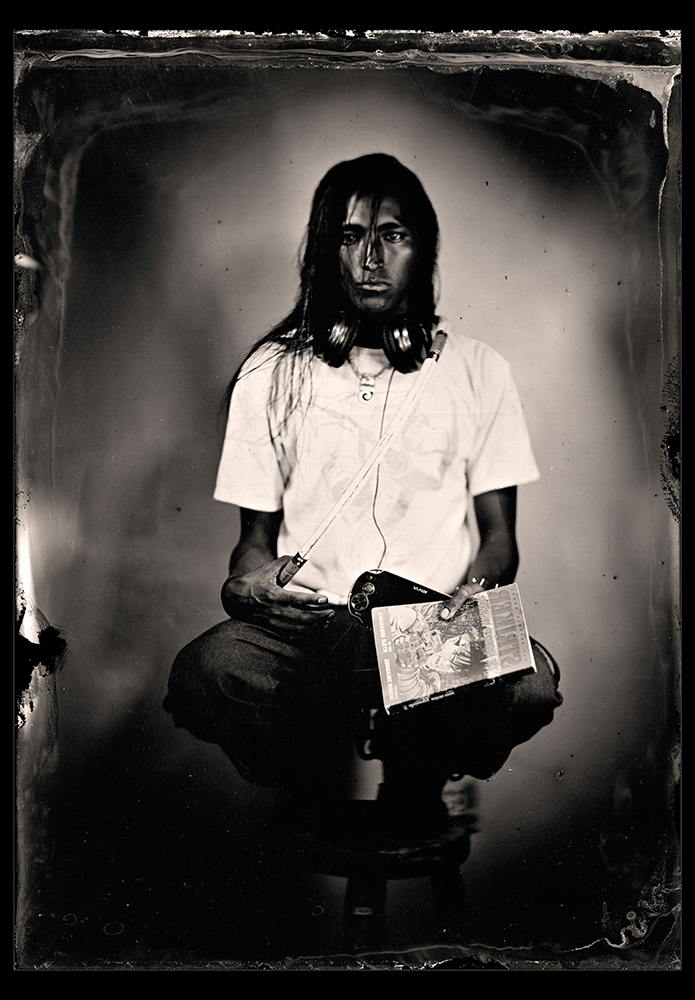

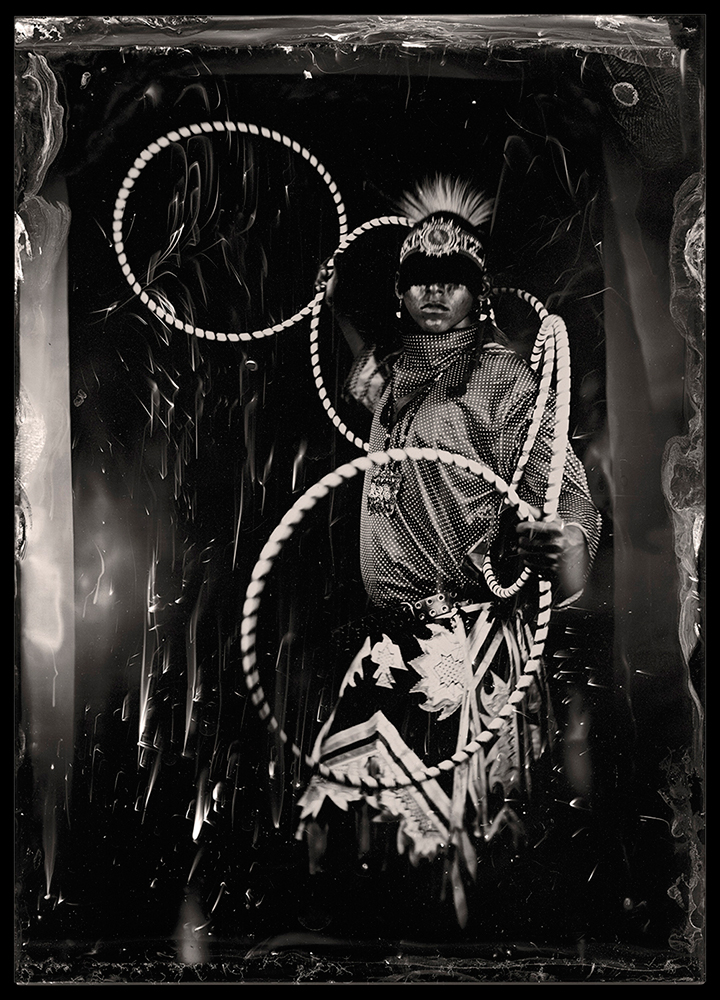

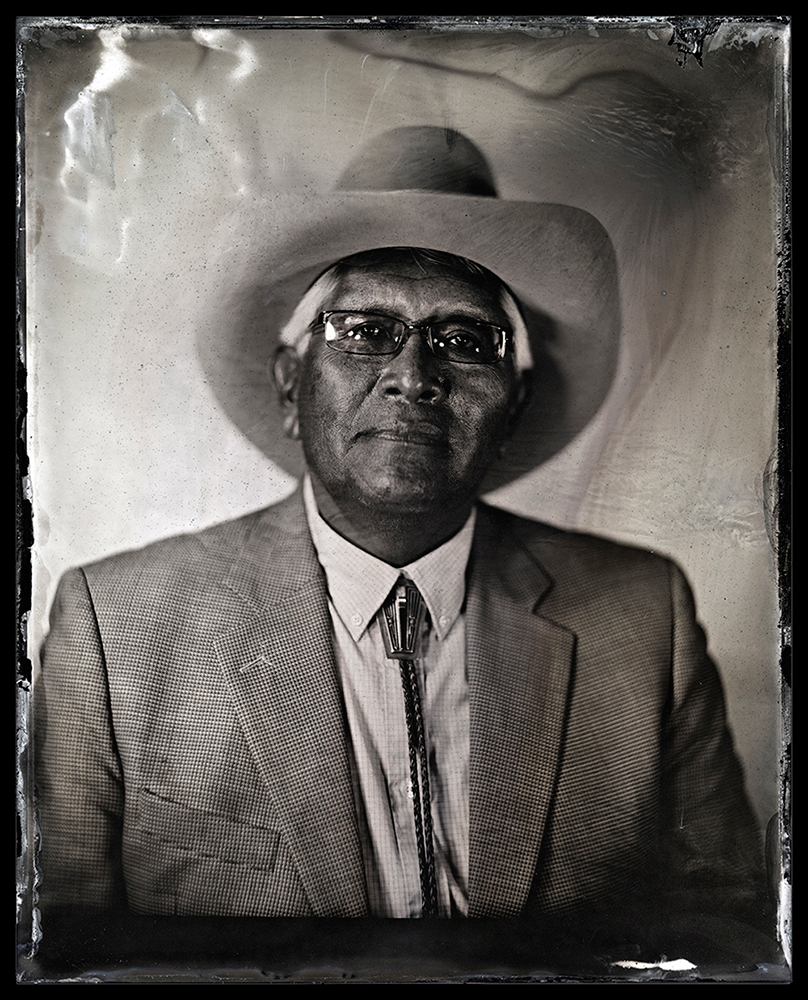

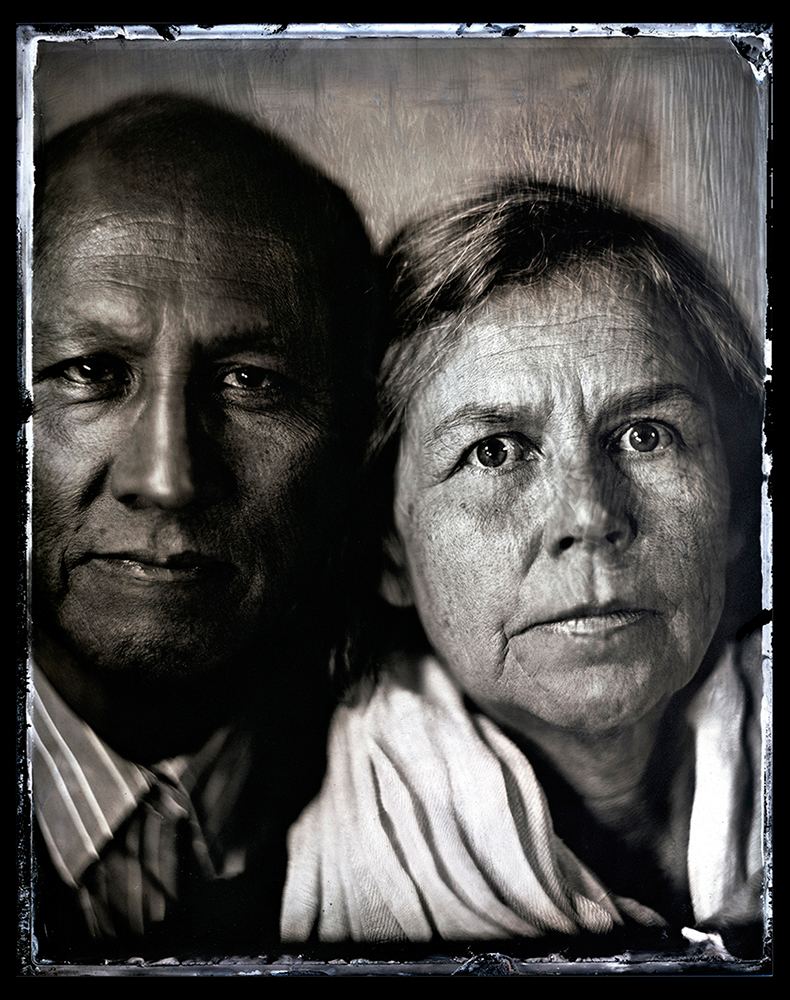

I propose to create a body of photographic inquiry that will stimulate a critical dialogue and reflection around the historical and contemporary “photographic exchange” as it pertains to Native Americans. My aim is to convene with and invite indigenous artists, arts professionals, and tribal governance to engage in the performative ritual that is the studio portrait. This experience will be intensified and refined by the use of large format (8×10) wet plate collodion studio photography. This beautifully alchemic photographic process dramatically contributed to our collective understanding of Native American people and, in so doing, our American identity.

In August of 2012, at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, I initiated the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX). This was the initial spark for an ongoing intervention into the history of photography that I plan to undertake. I aim to link history, form, and a critical dialogue about Native American representation by engaging participants in dialogue and a portrait session using the wet plate process. This multi-faceted engagement will yield a series of “tintypes” (aluminum types) whose enigmatic, time-traveling aspect demonstrates how an understanding of our world can be acquired through fabricated methods. Through collaboration with my sitters I want to indigenize the photographic exchange.

I will encourage my collaborators to bring items of significance to their portrait sessions in order to help illustrate our dialogue. As a gesture of reciprocity I will give the sitter the tintype photograph produced during our exchange, with the caveat that I be granted the right to create and use a high resolution scan of his or her image for my own artistic purposes.

Ultimately, I want to ensure that the subjects of my photographs are participating in the re-inscription of their customs and values in a way that will lead to a more equal distribution of power and influence in the cultural conversation. It is my hope that these Native American photographs will represent an intervention within the contentious and competing visual languages that form today’s photographic canon. This critical indigenous photographic exchange will generate new forms of authority and autonomy. These alone—rather than the old paradigm of assimilation–can form the basis for a re-imagined vision of who we are as Native people.

©Will Wilson, Bruce Bernstein, PhD, US citizen, former Director of the Southwestern Association of Indian Arts, 2012

©Will Wilson, Kathleen Ash-Milby, PhD, citizen of the Navajo Nation, Curator, National Museum of the American Indian, 2012

©Will Wilson, Terrance Houle, First Nations citizen of the Blood Tribe, interdisciplinary media artist, 2012

©Will Wilson, Joe D. Horse Capture, citizen of the A’aninin Indian Tribe of Montana, Associate Curator of Native American Art, Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2012

©Will Wilson, Cara Romero, citizen of the Chemehuevi Indian Tribe, Indigeneity Program Director, Bioneers, 2012

©Will Wilson, Kevin Gover, citizen of the Pawnee and Comanche Nations, Director, National Museum of the American Indian, 2012

©Will Wilson, Gaylord Torrence, PhD, US citizen, Senior Curator of American Indian Art at The Nelson-Atkins Museum, 2012

©Will Wilson, Zig Jackson, citizen of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, Professor of Photography, Savannah College of Art and Design, 2012

©Will Wilson, Nakotah Larance, citizen of the Hopi Nation, 6-time world champion hoop dancer, member, Dancing Earth, Indigenous Contemporary Dance Creations, 2012

©Will Wilson, Sandra Lamouche, First Nations citizen of the Bigstone Cree Nation, Dancer, Dancing Earth, Indigenous Contemporary Dance Creations, 2012

©Will Wilson, Nimkii Osawamick, citizen of the Ojibwe First Nation, Wikwemikong, Manitoulin Island Unceded Reserve. Dancer, Dancing Earth, Indigenous Contemporary Dance Creations, 2012

©Will Wilson, Raven Knight, citizen of the Jicarilla Apache Nation, Dancer, Dancing Earth, Indigenous Contemporary Dance Creations, 2012

©Will Wilson, Eric Garcia Lopez citizen of Tarasco First Nation, Dancer, Dancing Earth, Indigenous Contemporary Dance Creations, 2012

©Will Wilson, Ronald J. Solimon, citizen of the Pueblo of Laguna, Director, Center for Lifelong Education, Institute of American Indian Arts, 2012

©Will Wilson, Emma Noyes, citizen on the Colville Confederated Tribes nation, daughter and Stephen Noyes, citizen of the Colville Confederated Tribes nation, Institute of American Indian Arts alumni, inaugural class, 1962, 2012

©Will Wilson, Beverly Morris, Shareholder, Aleut Corporation, Documentary filmaker, independent curator, 2012

©Will Wilson, Lyn McMaster, Canadian citizen and Gerald McMaster, PhD, citizen of the Siksika First Nation, curator of Canadian art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Co-Artistic Director, the 18th Biennale of Sydney, 2012

[1] Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian, Norwood, MA: The Plimpton Press, 1907-1930, 20 volumes, 20 portfolios.

[2] See, for example, Jill Sweet and Ian Berry, Staging the Indian: the Politics of Representation, Saratoga Springs, NY: The Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College, 2001

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Robert Stivers: The States Project: New MexicoApril 3rd, 2016

-

Caitlyn Soldan: The States Project: New MexicoApril 2nd, 2016

-

Will Wilson: The States Project: New MexicoApril 1st, 2016

-

Kate Russell: The States Project: New MexicoMarch 31st, 2016

-

Laurie Tümer: The States Project: New MexicoMarch 30th, 2016