CENTER AWARDS: Editors Choice: Eric Kayne

©Eric Kayne, Jeanne Kilmurry stands in the road in front of her family’s property near Atkinson, Nebraska where the Keystone XL pipeline would enter their land.

This week Lenscratch will be sharing the CENTER Awards winners and the statements by the jurors to help understand their choices.

Congratulations to Eric Kayne for his Third Place win in CENTER’s Editor’s Choice Awards. Recently, Eric was also awarded the Carol Crow Memorial Fellowship, jurored by Maggie Blanchard of Twin Palms Publishers, which includes a solo exhibition at the Houston Center for Photography from May 13 to July 10, 2016.

Eric Kayne was born and raised in San Antonio, Texas. He took his first photography class in sixth grade and continued with photography on and off until he graduated high school. His vagabond academic life post high school took him to the University of California Santa Barbara, the Academy of Art in San Francisco, Collin County Community College, Austin Community College and finally the University of Texas at Austin, where he graduated with a BA in studio art.

In 1999, Eric moved to New York City, where he interned at Magnum Photos, Inc. and had a summer job at the Maine Photographic Workshops as the E-6 process manager. Later, while attending San Antonio College, Eric joined the school newspaper and discovered his love for photojournalism.

Following that, he had his first part-time staff job at the New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, eventually moving to a sister paper, the Brazosport Facts in Clute, Texas (home of the annual Mosquito Festival) for a full-time position.

After a year, he had had enough of life among the mosquitos and chemical refineries and moved to a small village in Marin County, California, living on the beach, driving a milk truck for an organic creamery, and freelancing for the Marin Independent Journal. Living in the Bay Area inspired Eric to continue his photographic education through workshops and classes at the City College of San Francisco. After two years, he left to attend the School of Visual Communication at Ohio University, eventually earning his MA in Photography.

After Ohio, Eric interned at the San Antonio Express-News, the Seattle Times and The Dallas Morning News. He eventually found a contract staff position at the Houston Chronicle. After 13 months, he was laid off, along with many others. Since that time, he has been an independent freelance photographer.

He now splits his time between editorial and commercial assignments, while creating as much time as possible for personal projects. His clients include Arcade Fire, The Wall Street Journal, Houston Methodist Hospital System, BBVA Compass Bank, H.E.B., and the MD Anderson Cancer Center.

His wife, Carrie Feibel, is the health and science reporter for the NPR affiliate in Houston. They have a three-year-old daughter, Joni.

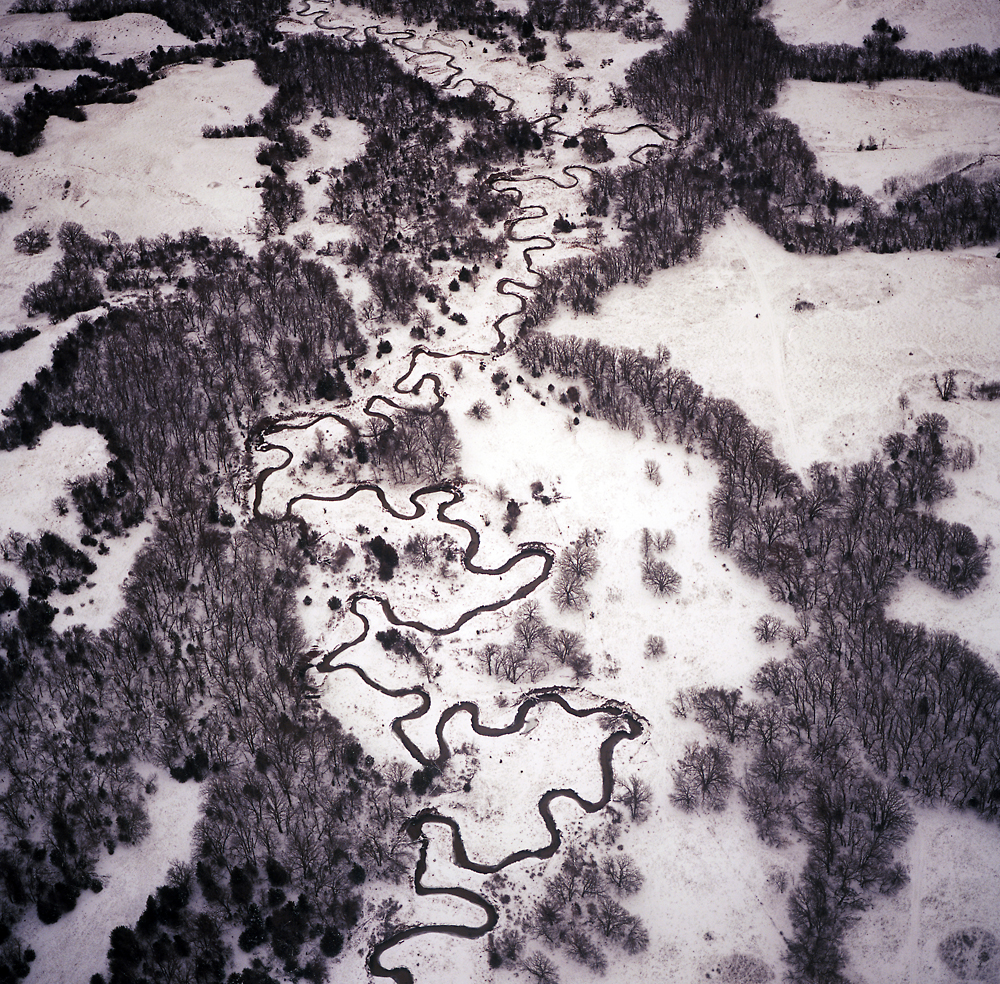

©Eric Kayne, A fire burns on a corn farm in Antelope county, along U.S. Route 275. The proposed Keystone XL pipeline would cross through large patches of farms and ranches in the county.

EDITOR’S CHOICE: Juror’s Statement

Chris McGonigal, Photo Editor, The Huffington Post

It’s not easy going one-by-one through beautiful images and being the one to make the hard choices on who has to go and who has to get left behind, but we all know in editing you have to make those hard decisions. It was such a pleasure to go through these entries. I based my decisions on those submissions on which I would think to myself “This would be really great for our site.” These images offer a view of something different, compelling and a series that just make us want to see more from their creator.

Third, but not at all least, are Eric Kayne’s striking photos that show the people and landscapes in the path of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline. The pipeline was definitely a divisive issue, and Eric’s photos are able to show us in perfectly framed images that there is beauty in these places that is at risk of being changed.

©Eric Kayne, A car sits in an early winter snow in Neligh, Nebraska, less than six miles from the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.

In The Pipeline’s Path

TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline (phase IV), now moot after rejection by the Obama administration, was a pipeline designed to duplicate a current pipeline but with a shorter route and larger diameter. Over a period of approximately six years, it had become a point of political contention and a symbol of many, and often contradictory, things: both corporate greed and job creation; energy independence and a disaster waiting to happen. Reading stories about it, I heard plenty from the adversaries on both sides – the oil producers and the environmentalists – but I wasn’t hearing, or seeing, enough from the people who lived directly in the path of the proposed pipeline. I wanted to photograph these people and somehow help tell their stories.

I decided to focus on the pipeline route through Nebraska. Unlike South Dakota, where only one rancher in the entire state refused to sign an easement to let the pipeline through his property, a substantial number of Nebraska farmers and ranchers organized their opposition, eventually forming a non-profit called Bold Nebraska to oppose the pipeline. Dozens had refused to sign easement agreements to allow the pipeline across their land. Nebraska also had the best available logistical information of all the states the pipeline would cross.

©Eric Kayne, An old Cadillac sits in the garage of Terry “Stix” Steskal in Stuart, NE. Steskal owns property that is in the path of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.

I spent a week in November 2014 photographing Nebraskans who were opposed to the pipeline from crossing their property. In July 2015, I went back to photograph people who did sign easements and would let the pipeline cross their property.

The ranchers and farmers I spoke with talked about being stewards of the land, not just for their own families and the generations before them, but stewards of the environment and of America’s food security. They feel there was nothing good about the pipeline. It could be bought and sold long after it was put into the ground; it could have even be sold to a foreign country. It would have been filled with a sandy, corrosive substance that could abrade and degrade the inside of a pipeline, causing a spill. Tar sands contain benzene, a suspected carcinogen that sinks in water. The pipeline would cross the Ogallala Aquifer – one of the world’s largest – and any leak would threaten to pollute this precious resource.

©Eric Kayne, Jake Crumly, 15, left, father Ryan Crumly, and Zach Crumly hunt for deer on opening weekend on their family’s property near Page, NE. The proposed Keystone XL would cut through their family’s property.

Among the ranchers and farmers who did sign easements, the prevailing attitude was that the pipeline was like any other financial decision that affects their business. Farming and ranching is very expensive, and the extra income seemed to be a welcome addition to their volatile bottom lines.

My motivation was to make compelling images of those who live in the pipeline’s path. TransCanada, the pipeline builder, has deep pockets and even has a polished corporate website featuring photos and video of happy landowners who sold easements to the company. My hope was that my photo essay, in some way, would help to balance out the issue, giving voice to those still fighting on their own for a different pathway, both for this project and for our collective environmental future.

©Eric Kayne, Members of the Kilmurry family stop and talk while moving cattle from one field to another during a snowstorm, Atkinson, Nebraska. The Kilmurry’s have rejected TransCanada’s attempts to get them to sign an easement to let the Keystone XL pipeline cross their property.

©Eric Kayne, Rosemary Kilmurry, 93, in her living room near Atkinson, NE. The proposed Keystone XL pipeline would cut through her property.

©Eric Kayne, A funeral takes place at St. Boniface Cemetery in Elgin, NE. The town is eight miles away from the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.

©Eric Kayne, Wind generators stand near the property of Mike Blocher’s home and horse ranch in Oakdale, Nebraska. The proposed Keystone XL pipeline would cut through his property. One of Blocher’s concern’s is based in experience. While the wind generators were being built, ownership changed numerous times. He said the same thing can happen to the pipeline, that it’s ownership could become even more remote than TransCanada is to most property owners opposing the pipeline now.

©Eric Kayne, Jeff Jansky, a pig farmer in Milligan, Nebraska, signed an easement allowing the proposed Keystone XL pipeline to cross his property.

©Eric Kayne, Doc Holiday, manager of The Dunes Motel in Albion, Nebraska. Albion is four miles from where the proposed Keystone XL pipeline would be constructed.

©Eric Kayne, A parade float heads back to a parking lot following a parade in Albion, Nebraska at the Boone County Fair. Albion is four miles from where the proposed Keystone XL pipeline would be constructed.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025