CENTER AWARDS: Exhibitors Choice: Jennifer Greenburg

Congratulations to Jennifer Greenburg for her third place win in CENTER’s Exhibitors Choice Awards. Her continuing series, Revising History, allows her to visit the past as she inserts herself into vernacular photographs. As she states, “My intervention in these found vernaculars is how I hope the series engages the audience in a conversation about the way we interpret the media, record personal memories, and establish collective history”. Currently, Jennifer has a solo exhibition at jdc Fine Art in San Diego, CA running through May 28, 2016, curated by Jennifer DeCarlo.

Jennifer Greenburg is an Associate Professor at Indiana University Northwest.She holds an MFA from The University of Chicago and a BFA from the School of the Art Institute. Solo exhibitions of her work have been held at the Hyde Park Art Center, The Print Center, and many other places. Greenburg’s work has been included in numerous national and international group exhibitions. Light Work awarded her an Artist in Residency in 2005. Her work is part of the permanent collections of Light Work, the Museum of Contemporary Photography, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and the Museum of Photographic Arts. Jennifer Greenburg’s monograph, The Rockabillies, was published by the Center for American places in 2009

EXHIBITOR’S CHOICE: Juror’s Statement

Rixon Reed, Director & Founder, Photo-eye Gallery, Photo-eye Bookstore

The overall quality of the submissions to Center’s Awards this year made it extremely challenging to choose only three bodies of work for the new Exhibitions Choice Awards. Each of the following projects could easily capture a viewer’s attention and spark their imagination when shown in galleries or on museum walls. In Reviving History, Jennifer Greenburg seamlessly inserts pictures of herself into old family photos lending a little humor to our troubling times. It’s a new kind of fantasy performance art that is deftly done.

These artists are smart in their approaches and have conceptually and aesthetically compelling projects. It’s work that can be returned to again and again. Additionally, I’d like to acknowledge the following artists whose work I also found particularly engaging, thus making it difficult to narrow it down to three primary choices. Michael Courvoisier, Alejandro Durán, Klaus Enrique, Jennifer Greenburg, John Hathaway, Kevin Horan, Isabel Magowan, Ben Marcin, Justyna Mielnikiewicz, Jessica Eve Rattner, J.P. Terlizzi and Marta Zgierska.

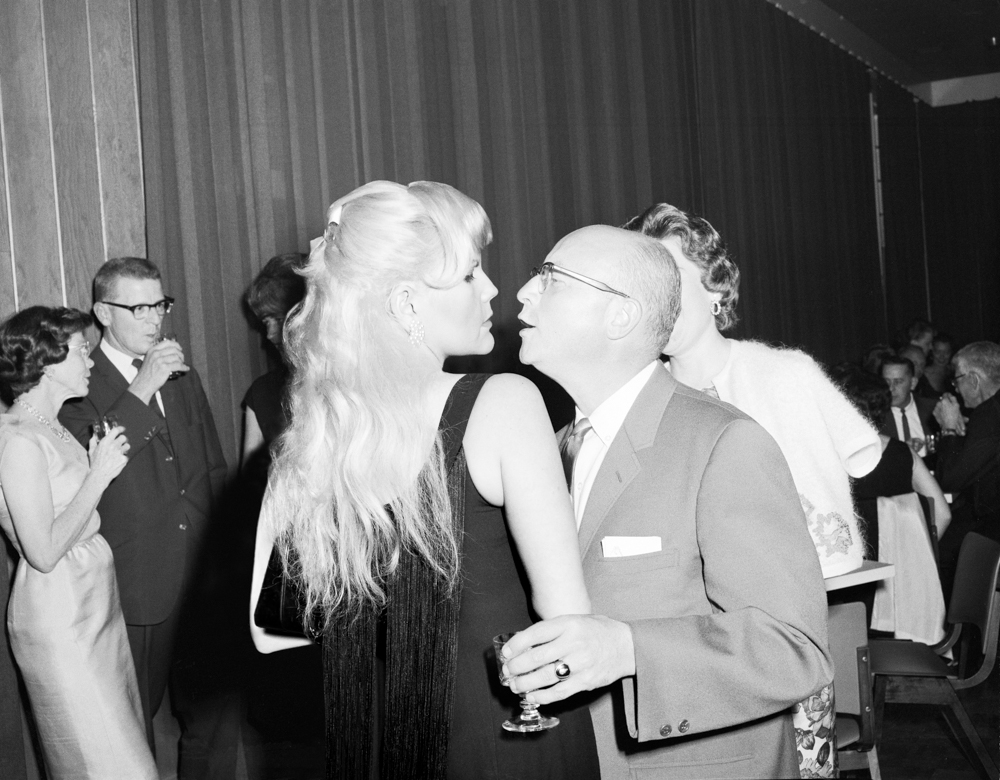

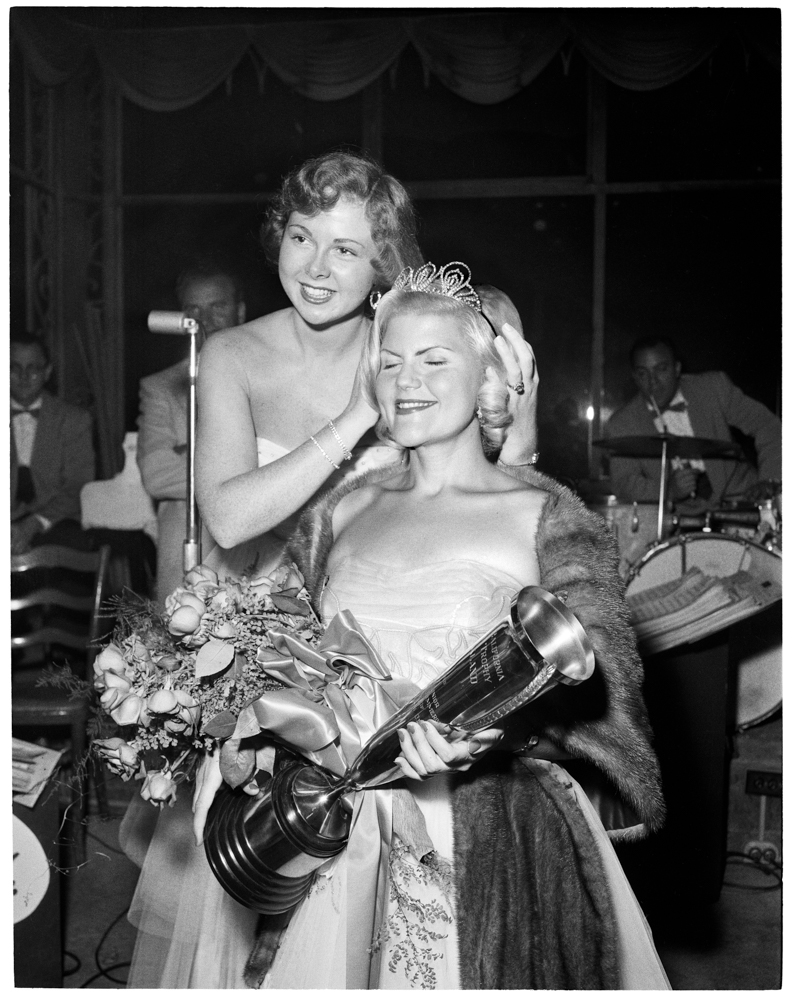

Revising History is a study on photography, the nature of the vernacular image, and its role in creating cultural allegories. The work intends to create a dialogue about the photograph as simulacrum- the moment versus the referent. To engage these layered truths I replace the central figure in found midcentury (1940’s –1960’s) vernacular photographs with an image of myself. In doing so I effectively hijack the memory and create a “counterfeit” image. Most do not stop to think about the ubiquitous nature of the camera or the impact of pictures, but snapshots now intervene in almost every aspect of life – the pinnacle and the banal. The danger in this is we seem to have forgotten that the picture liberates the moment from reality, erases vantage, and is inevitable susceptible to co-opted or underwritten fantasy.

Early works in Revising History speak to idealized moments. I become something of a period heroine graduating from finishing school, singing at a St. Patrick’s Day party, performing a perfect swan dive, and more. Recent additions to the series begin to break these conventions, and include awkward moments or point to historical oversight. Mid-century America is often idealized as a purer, simpler time, when it ought to be remembered for its inequity and stirring unrest. Images help us remember selectively, and the myth around the period perpetuates, in part, via collective vernacular contributions.

My studies of vernacular photography lead me to conclude that we share nearly identical visual narratives. Documented moments are parallel if not nearly identical. I have further discovered that conventions of composition, lighting, and expression are closely followed without much variation. If such visual conventions underpin vernacular photographs, then it is reasonable to infer that the end result is not particularly unique to the person or place represented within the image. The end result is merely a duplicate of all other similar image-types. It is as if we are making these images to prove not only existence but also to testify belonging, happiness, and our accomplishments. However, these images prove our conformity more than our uniqueness. The purpose of transforming the “originals” is to underline existing and universally understood allegories. The creation of the “counterfeit” transmogrifies the “original” into an iconic symbolization of a type of moment. My intervention in these found vernaculars is how I hope the series engages the audience in a conversation about the way we interpret the media, record personal memories, and establish collective history.

©Jennifer Greenburg, Two years later, I was drunk enough to sing at the St. Pat’s Party. How embarrassing! 2014

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025