Ken Weingart interviews Farrah Karapetian

Today, I am sharing an interview that photographer and blogger, Ken Weingart conducted with photographic artist Farrah Karapetian. Ken has been producing interviews for his Art and Photography blog, and he has kindly offered to share his interviews with the Lenscratch audience.

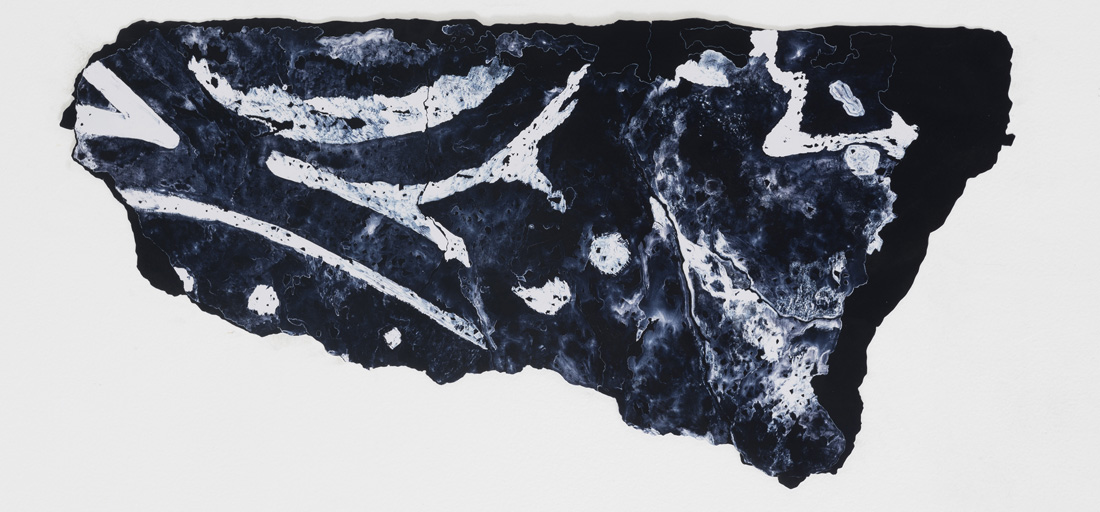

Farrah Karapetian is a renowned Los Angeles-based conceptual artist who creates stunning imagery through photograms or “cameraless” photography. She studied as an undergraduate at Yale University and received her MFA at UCLA. She recently had exhibitions at Danziger Gallery in New York City and the Von Lintel Gallery in Los Angeles.

When did you first think of becoming an artist?

As a child, I was a good draftsman. I drew often and well, but I never felt as if I were learning, per se, in this or other subjects: one thing did not lead to another. I also read and wrote a lot, and entered college considering creative writing, religious studies, and Russian literature majors as much as the art major. Through my first year in taking a diversity of such classes, that feeling persisted of not really having found a practice that would gather its own steam. My father gave me a 35 mm camera for Christmas my sophomore year and I took my first photography course, and in this course, I first identified that feeling of learning from my own practice. I could see my thoughts unfold in the prints on the wall week after week: how I saw, how I moved, how that changed over time. One picture led to another; life led to the pictures; I had only to observe that unfolding and be responsible to it. I am still responsible to it.

You are known for creating “cameraless” art. Does any of the work originate from a camera?

It’s true. The majority of my practice involves cameraless photographs – or “photograms” – and the making of sculptural negatives en route to their exposure. My sculptural negatives are three-dimensional objects the bodies of which operate according to the logic of light. I am not at all interested in the cameraless photograph as such, however; my practice is not driven by anachronism. I am interested in how images exist in the world, and a lot of my cameraless work examines existing photographs and reimagines the way that they circulate. Cameralessness makes that process of reimagining more physical and present and drawn out for me than do other photographic processes. In a sense, however, you could say that if I am influenced to make a cameraless photograph from a photograph I’ve seen circulating online, that cameraless photograph originates from a photograph taken with someone’s camera.

Because I am interested in received imagery, I do very very occasionally decide that a certain type of conventional photography will be more useful in articulating an idea than would be a cameraless photograph. For example, I appropriated the cultural function of the typical engagement photograph for my piece, Ringtan, 2007. At the time, I had broken off an engagement, and I had a tan around my absent engagement ring – a kind of photogram, I suppose. I had myself photographed by an engagement photographer in the pose typical of a woman having her ring finger photographed, and the print that resulted was scaled to 7 x 5 inches – also typical of that kind of photography. In that case, then, what I was trying to communicate about memory and its inscription on the body was more specifically addressed by borrowing from norms of how photographs are taken than it would have been addressed by the physical process of making a photogram.

How did the idea of photograms come about, and what is the process? How laborious is it?

My experience of photographs in college and immediately afterwards was that any one print I made was a unique object, and that as such it had as much plasticity as did any painting, sculpture, or artifact of process. Making a photograph could entail decisive choices regarding palette, scale, additive and subtractive processes, and more – both within the picture plane and with respect to the print as object. The process of printing the thing could and should have an effect on the result as much as the process of creating the negative. I was sure of all of these things but not satisfied with the difference between the event of exposing a negative with a camera and exposing a piece of photosensitive paper in the darkroom.

I made my first photogram by mistake after my one and only editorial assignment: a trip to Kosovo to photograph the politics of architecture. I returned to New York from that trip and, printing the images of burned villages, grew frustrated with the difference between the two sites of exposure and slammed a fan down on the enlarging table, mistakenly tripping the enlarger’s light. When something comes between the photosensitive paper and a light, its silhouette is burned into the paper: this happened, then, by mistake, at that time, and recorded of course my current state of mind as much as it recorded the silhouette of the fan on the paper. I liked that conflation of the time and space of exposure, and decided that that’s how I would work from then on, so I stopped using cameras.

A photogram can then be the least laborious of processes, in terms of its necessitating only an intervention between the paper and the light at the time of exposure. The way I work, though, it can be very laborious, because I began to construct negatives and direct scenarios that would be staged in the darkroom. This was helpful for me in general as well, because I wanted to have parts of my process that would entail structured thinking and planning and parts of my process that would entail an openness to chance. The exposure of the photograms became the latter, and the construction of the negatives became the former.

Your print sizes are fairly large. How do you decide how big to go? What is the usual edition?

They are not large as a rule, per se. A photogram generally records the shadow of a thing at one-to-one scale or larger, so if I set up a scenario involving a life-size person or people, or an object that is, at life-size, fairly large, then the print of that thing in its totality will be at least as large as the thing itself. I do occasionally photogram small things or parts of larger things, and in these cases, the prints are more modestly scaled. I do, however, have as a goal that a picture relate to my own body or the body of a viewer at a scale that is recognizable and credible as far as how we experience the thing pictured when it is real. Photography as it is conventionally practiced has no relationship to scale as an abstract concept: prints are usually small if the photographer believes the image should be intimately related to its viewers or large if the photographer believes that monumentality is an issue for the work. I wanted my work to have scale built more logically into the prints’ physical existence, and photograms, with their one-to-one baseline, solved that problem, initially. By now they have become more complicated for me, because I have begun to use shadows of objects at scales larger than life, but I rarely force the scale of a shadow into smaller relief than is conventional to the object pictured. There are no editions of any photograms, because photograms are unique and irreplicable objects. There are no editions of any sculptural negatives, either, although for example I made three resin casts of the sets of weapons used by the veterans in my Muscle Memory series, because there were three veterans available to hold the weapons. Each of those casts is slightly different from the other, though, because difference is implicit in the nature of any object. No two things are ever the same, existentially. The edition is a fallacy created by market forces, and I don’t find it interesting at this time.

You work mostly without people in your concepts. How did this preference come about?

I do not, actually, work without people. Almost all of my projects begin because of an interaction with a person and involve the deployment of people in the darkroom at some point. While I am working towards or away from a figurative piece, however, I spend a lot of time with the objects associated with any given scenario, and I free myself of the boundaries of the origin story of the project by over-familiarizing myself with the objects until they become rife with as much abstract potential as narrative.

How do you come up with your ideas and themes? Is there a dominant idea or favorite concept you like to explore?

I am always following the thread of my life and practice. Although the bodies of work may appear distinct to other people, they are truly all linked for me in terms of the development of an abstract language over time. You can follow that particular thread – how I use light, three-dimensionality, performance, and the space of a room or page. You can follow the thread of my psychological relationship to issues of memory, authority, and surrender. You can follow the thread of questions I ask with respect to ontologies of sculpture and photography. You can follow my engagement with mass media and how I reconfigure its missives inside of the language of my practice. You can follow these as a series of questions and answers, calls and responses that evolves over time.

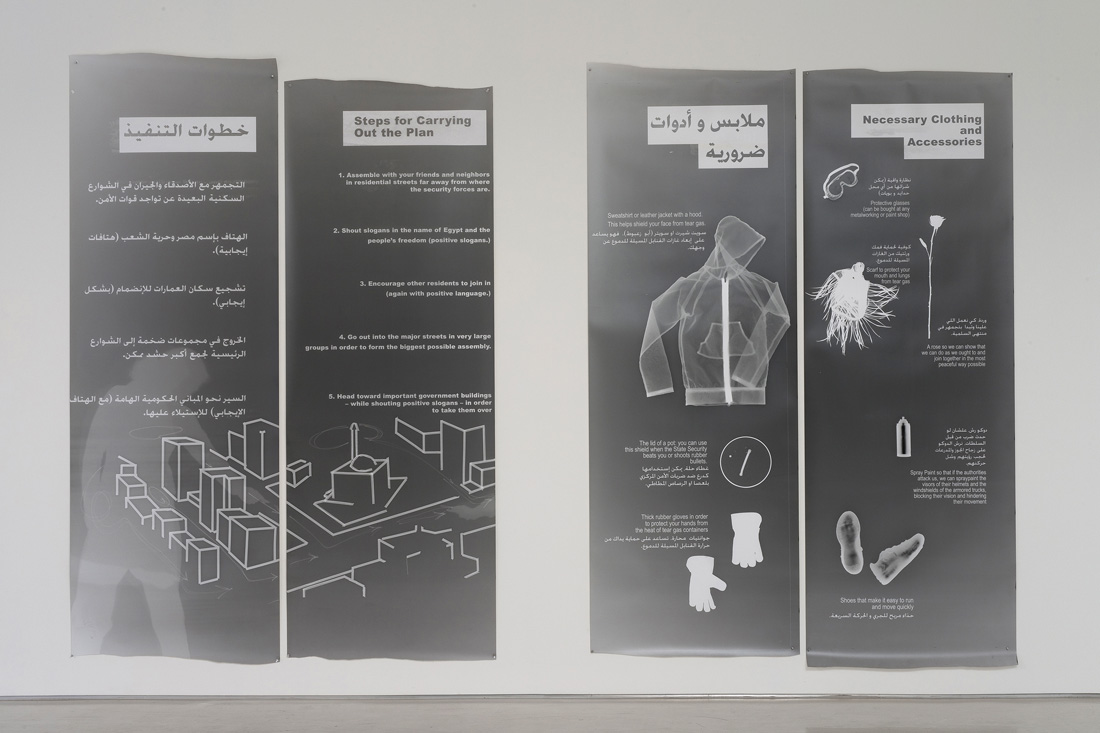

Or… you can do what most people do and say that each body of work is distinct and has only to do with the portrayal of a distinct subject: war, protest, surveillance, music, etc. This may seem to be the easier default strategy of a viewer, but it is actually the most difficult way to try to make sense of my work over time. As a 21st century citizen, I – as do you – engage with any number of politics on a daily basis: those local to my feelings and body, those local to my family, my tastes, my city, my nation-state, those local to my travels, those local to my experience of global news. Global politics enter my life – as they enter yours – via the internet and radio, but also via personal experience and associations. I encountered “war” as a subject because I was teaching a course in photography and one of my students was a veteran of the US Special Forces and came to me with a memory he wanted to reenact for me. I was also at that time offered the opportunity to work in a space that had a very particular entryway, and so we designed our project around the idea of him and his teammates reenacting the muscle memory of stacking the door of the gallery as they might have stacked and breached the door of a target overseas. I encountered “protest” as a subject because I was likewise personally and abstractly motivated: I was thinking about Greco-Roman relief sculpture and the way it occupies architectural pediments and at the same time the mother of my boyfriend’s daughter was handling one of the architects of the Egyptian revolution and passed onto me a pamphlet instructing Egypt’s citizens in the art of unrest. A body of work, then, is something of a fallacy insofar as it exists in a train of thought and process and life experience, and is not distinct from the bodies of work that come before it except insofar as each new subject instigates new strategies for representation and abstract terms.

For your series, Absence and Ruin, what were you trying to say?

This is not a series, per se; it is a running theme throughout my work. I have noticed over time that a lot of what I focus on is the negative space around an event: its aftermath, its inversion, its artifacts. Photography and sculptural casting lend themselves naturally to these ideas, both metaphorically and literally.

When organizing a website or any kind of portfolio or book, one is forced to sort. The sort is in itself infinitely rearrangeable. Some bodies of work seem to begin and end during distinct time periods and be nameable, such as the work around surveillance or war. Others result in distinct pieces, but recur over time. This is actually more the way a sculptor might work than a photographer; photography conventionally emerges for the public in bodies, and sculpture does so with less frequency. I do now turn an idea around and around more frequently than I used to, and this results in identifiable bodies of work more frequently than my practice used to, but I am also totally comfortable recognizing that sometimes I make a piece and it just is what it is, unlinked to the work I am making in immediate concert with it otherwise in the studio. Usually, it is linked to work I have made before and will make later, because I am the one making all of it, and I have particular psychological threads as a person and as an artist.

The work I put into the category of “Absence & Ruin” on the website has relationships to all the other series, in other words. The piece, Ruin I, and the installation, Rock, Paper, Scissors, both bore the work you see elsewhere on the website called “Slips.” The piece you see in “Absence & Ruin” called “The Kitchen and Its Negative” bore pretty much all of the work I’ve ever made since then, because it was the first time I had made a sculptural negative, the first time I had actualized the difference between pictorial and architectural space, and the first time I had conflated a personal narrative and a political one quite so concisely. (I made that piece after breaking off an engagement with a fiancé and also after a trip to Hiroshima to look at shadows burnt into buildings after the bomb.) The piece, Souvenir, is a trace of a fragment of the Berlin Wall and of the graffiti on that fragment, and shows the marks of frustration citizens make on public spaces. This of course is related to the work in the category of “Social Control.”

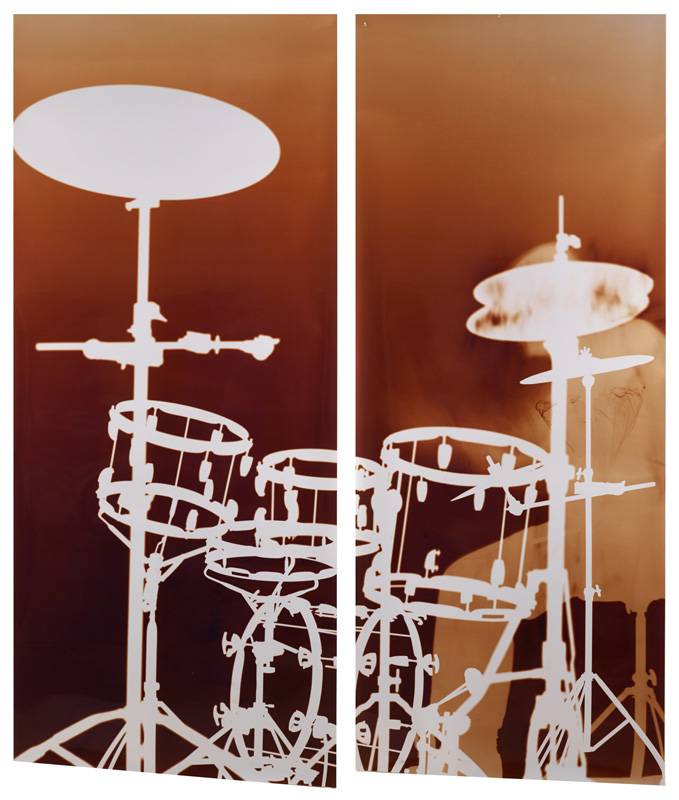

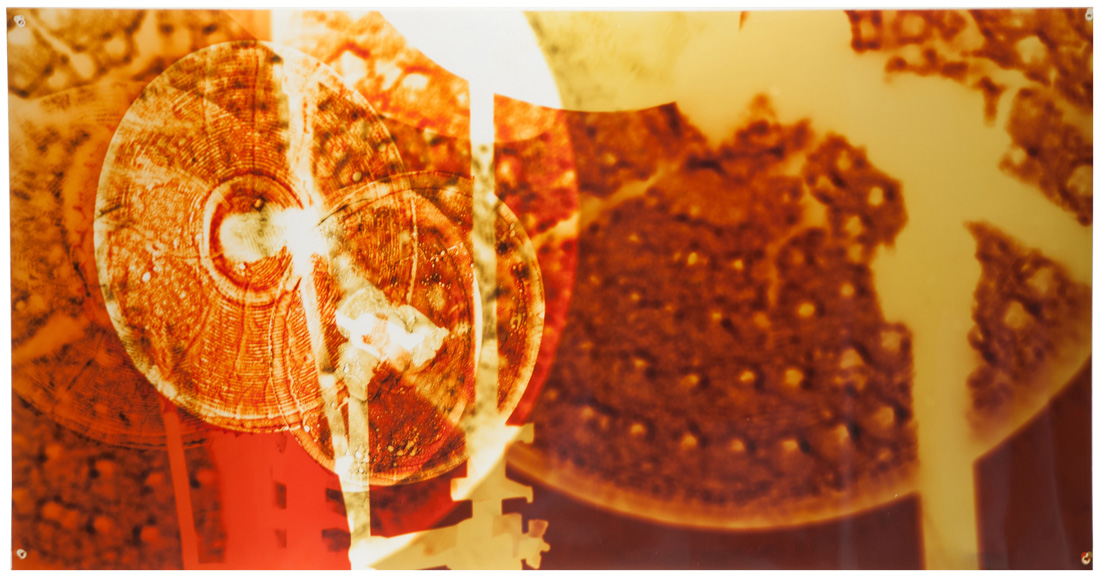

In, Stagecraft – Soundscape, you explore musical instruments. Is music a great passion, and was this series created with the photogram process?

No, I don’t generally listen to music. I began to look at music first because I was considering going to Afghanistan to work on a music video with a group of young people who were rapping and playing heavy metal despite the disapproval of the Taliban. I was impressed by their need to express themselves despite their circumstances, as I am usually impressed by individual will and its dominance over authority, but I didn’t end up going to visit them. At that time, my father was practicing his drums in my studio because noise doesn’t matter in my house as it does in his. My father gave up his professional career in drumming before I was born, and so the drums represent to him a kind of loss; they also, at the same time, represent a real source of relief, and they always have for him, even when I was growing up. My father had also recently been diagnosed with cancer, and I wanted not only to begin to understand music as a field, but also my father as a person with a passion. His drum kit is very specific to his body, as are most drum kits specific to the body of their musician; in this, it is already a kind of sculpture, but what art does is observe that and exaggerate it. So I remade his drum kit as a sculptural negative: the drums and stands existing only as skeletal armature and the cymbals cast in glass. This has a literal function insofar as it translates photographically into volumes and lines, but it hopefully also has a metaphorical function insofar as it removes the musical functionality of the drum kit and turns the object into something of a surrogate for the body of a person I will at some point lose. I then, yes, used this negative and the bodies of my father and others and the objects of some other related musical instruments to make photograms.

In Social Control, you explore guns, war, and violence. What inspired you for this series? Did you hire models to pose with the rifles and shields?

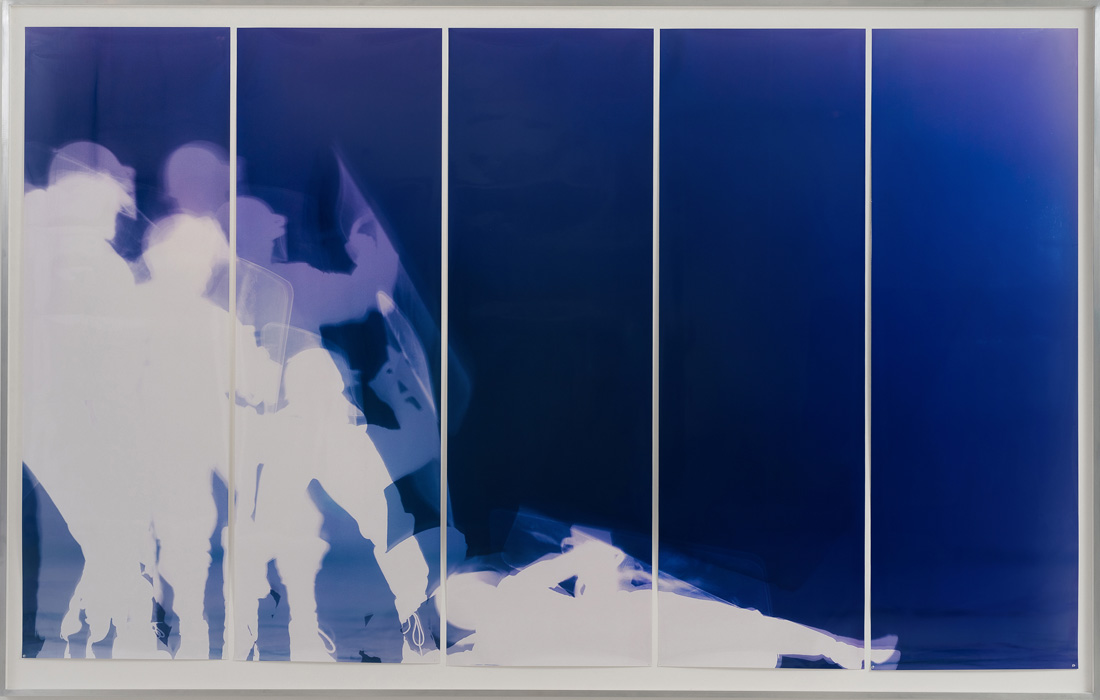

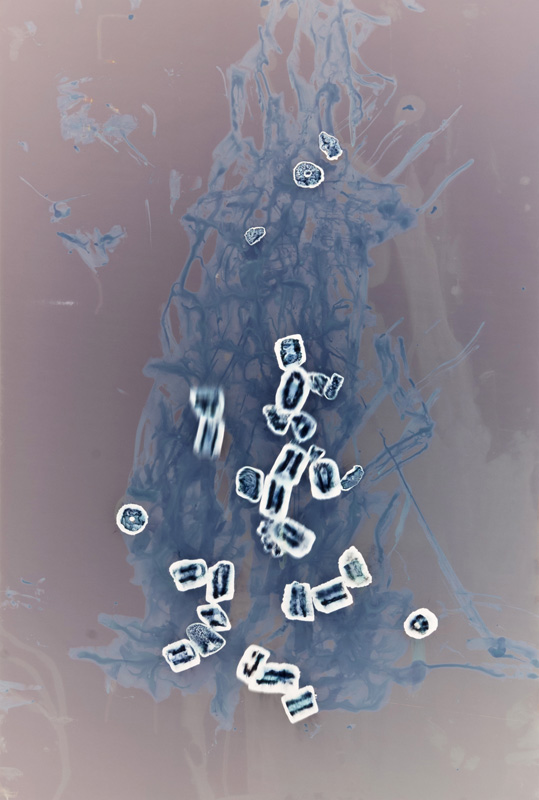

Again, this is not a series, per se. “Social Control” is a category that my website employs to suggest that the work I made with veterans’ memories (Muscle Memory), with the document distributed at the time of Egypt’s revolution (Accessory to Protest), and the problem of the Z-Backscatter scan deployed at international borders (Surveillance) might fruitfully be compared. In the case of Muscle Memory, the piece was inspired by and reenacted by veterans of the US Armed Forces. I had asked them which objects they would need in order to best remember how to hold their position, and they said these particular weapons, so I remade their weapons in clear resin. In the case of the Stowaway piece in the Surveillance series, I asked the man who worked on my building, Juan, to be in the photogram of the illegal immigrant inside of the U-Haul truck. In the case of Accessory to Protest, most of the work is object oriented, but the large black and white piece, “Flyer Photograph”, involved the body of one of the architects of the Egyptian Revolution, Ahmed Maher. To make this piece, I remade as sculptural negatives in cast resin all of the objects the pamphlet said would be necessary for civilians to stage a revolt. To make “Riot Police”, also part of Accessory to Protest, I asked my friends to study a photograph I had seen in the news of riot police being stoned by protesters in Kyrgyzstan. I gave them riot shields and helmets I had ordered off of the internet and told them to play-fight for a minute or two to rough up the Plexiglas. Once they were done, they reenacted the scene from the photograph. I suppose that would be the closest to a hired model situation of any of these three bodies of work, because my friends are very much not riot police themselves. The orientation of each of these figurative works, though, in any of these series, is such that I am not claiming a direct relationship to the event itself – war, immigration, or protest – but that I am claiming a direct relationship to viewership of the document – the picture of the protest circulated on the internet, the pamphlet circulated before the revolution – and that I want to engage more deeply than the internet affords in what that viewership can be.

You received your BA from Yale and MFA in fine art at UCLA. Who did you study with and what was the lasting affect on your work?

I studied photography at Yale, and my BA is in Fine Art. My teachers there in photography were Lois Conner, Tod Papageorge, and Gregory Crewdson. My thesis committee at UCLA consisted of James Welling, Charles Ray, Mary Kelly, and Lari Pittman. Yale gave me a firm foundation in photography’s conventions and history and a sense of its poetic potential and the boundaries one might test with further fluency. UCLA gave me a studio and therefore the space to test those boundaries against three-dimensionality. Charles Ray was a wonderful influence with respect to issues of scale. Mary and Lari were wonderful influences with respect to the social implications of any one of my gestures. James and Catherine Opie were wonderful readers of photography and James in particular has remained someone I engage with outside of the context of the institution.

How did the relationship with the prestigious Danziger and Von Lintel galleries come about?

Well, these things are difficult to put one’s finger on. I do remember that the first review I ever published was about a Marco Breuer show at Von Lintel when the gallery was based in New York. (I write sometimes, when I want to sort something I’m thinking about out otherwise than in the studio.) Thomas (Von Lintel) doesn’t remember that, though, and I don’t think I talked to him then. He contacted me on Facebook years later after my Accessory to Protest show, I think, and had heard of the work in part because of the Artforum review, in part because a curator at the Getty had mentioned him to me, and also I think because of other mentions. We began working together informally when he was moving to Los Angeles and I helped put together his first exhibition here. He took some of my work to a fair; it did well; he offered me a show; and everything has worked out between us quite nicely. Similarly, James Danziger had heard of my work through a variety of channels and talked to Thomas about it at a fair. He then came to my studio and proposed a show. Really most relationships in life and in art come about similarly: people come into one’s life and one tests out dynamics and sticks with those that feel good and work out well.

Elton John has bought some of your art. Did you meet him and how did that transpire?

No, I haven’t met him. That sale occurred at LEADAPRON, the gallery to which Diane Rosenstein had brought my Accessory to Protest work, and was the result of Jonathan Brown’s communication with Elton John’s curator.

You have won many awards and fellowships. How important are they, and which ones stood out the most for you?

Each award is of course very important for many reasons. Some are simply recognitions of engagement, which is of course an honor and a pleasure to receive in return for services rendered; others involved small sums of money that really were helpful at the time, as encouragement and as literal funding towards getting something done. Others enabled deeper engagement over longer periods of time because of the amount of funding provided, such as the Artswriters grant from the Warhol | Creative Capital Foundation, the Artistic Innovation grant from the Center for Cultural Innovation, or the Mid-career Artist Fellowship from the California Community Foundation. As one proves that one follows through with one’s funded projects, one is more likely to be awarded greater sums of money, because one demonstrates repeatedly that one can handle and derive consequence from the funding. I mean, I hope that’s the case and that my work continues to receive support in terms of faith and funds from grant-making institutions. I suppose over time these are a record of the growing consequence of what one continues to contribute to culture, and that they should be taken seriously in that regard as bars to which one sets one’s sights. What do I owe to culture when culture places its faith in what I do? I take these gestures as seriously as do I take moments of institutional acquisition: if the work is in larger and larger conversation with others’ accomplishments, how much more can I articulate its contribution?

When you do residencies, what does that involve, do you enjoy it?

Residencies can be very disruptive, and so I do them selectively – at times in my life when I need to get away from my resources and take in new information from new communities and places. One sets up one’s studio so that one has everything one needs – from a pickup truck to scaffolding – and so to leave that comfort zone can be very awkward and sometimes expensive. I usually plan to fall apart while traveling at least once, and then to rebuild before I return. I remember being at MacDowell and having lunch delivered to me and feeling very taken care of, which was lovely; at universities I have visited, I have come in contact with wonderful new conversations and perspectives on the place of art in the academy rather than in the market. These experiences can and should be refreshing. I also travel for influence outside of the residency structure. What I usually have to remember is that new work may not be generated while away to the extent that it is generated upon return.

What are your long term goals and ambitions? Do you plan on teaching one day, and if so what and where?

I want to be happy. That’s not what you mean, though. I would like to see my work understood well without the confines of the photographic field and outside the confines of the cameraless photographic field. I want to understand the ways in which what I do is in conversation with what others do, in many fields, even outside of art, let alone photography. I want a fiction writer or a creative non-fiction writer to analyze my work at some point, rather than an art critic. I want a choreographer to speak to me about the performative aspects of what I do. I want a political scientist to talk to me about the ways in which what I do aligns with or departs from what he or she does. Shows in new geographic regions are one way to address that conversation to new audiences. Shows that bring together multiple bodies of work are another way to re-sort one’s work according to fuller significances.

Teaching is another way to understand that conversation as being consequential, and I do enjoy teaching for that reason. Artmaking can be a very solitary experience, and it is nice to have the community of a university setting in which to relay ideas. It is also refreshing to speak with younger artists; such conversations usually create new neural pathways through old arguments one has constructed for oneself around art practice and art history and art markets. It’s useful and its fun. I haven’t yet found the university setting into which I think my presence would best be used, but I love visiting universities in the meantime. I know that I’m most useful when teaching in an interdisciplinary context, because although I love and come from photography it is not all that I think about. I prefer universities to art schools because I think it useful to have multiple subjects at the disposal of students and faculty rather than isolating either part of the community within the conversation of art practice. I like the feeling of mentorship that comes from the studio visit dynamic with graduate students, and I appreciate the feeling of novelty that comes from introducing basic practices and core questions of representation to undergraduates. I prefer the potential to cultivate pedagogues that would come from being full time faculty to the peripheral situation of the adjunct.

I think in the end that art has always been my way of engaging with the world; visual analysis comes instinctively to me and I spent a lot of my childhood drawing in museums and from books of reproductions. To be a part of how another child grows up configuring the world and organizing their thinking around how that world can be seen and stretched… that’s I suppose one way to understand a long term goal, and one way to be happy in one corner of one’s life.

Farrah Karapetian (1978 US) is an artist currently based in California. Her methods incorporate sculptural and performative means of achieving imagery that refigures the medium of photography around bodily experience. She has had multiple solo exhibitions and is represented by Von Lintel Gallery (Los Angeles, CA) and Danziger Gallery (New York, NY.) Upcoming exhibitions include A Matter of Memory, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY (2016); The Surface of Things, Houston Center for Photography; and About Time: Photography in a Moment of Change, SFMOMA, San Francisco, CA (2016.) She will be in residence in May 2016 in St. Petersburg, Russia, with a grant from CEC ArtsLink.

In 2014, she was recognized with a California Community Foundation Mid-Career Artist Fellowship. She received a grant for Artistic Innovation from the Center for Cultural Innovation in 2012 and was a resident at the MacDowell Colony in 2010. She has received support from the following sources as well: the Foundation for Contemporary Art (Emergency Grant 2009); Hoyt Scholarship (2008); Lillian Levinson Scholarship (2007); UCLA Fine Arts Travel Grant (2007); Corine Tyler Walker Prize (2007); Sudler Fellowship (2000, 1999); Richter Fellowship (1999.)

Karapetian’s writing about photography and visual experience has been recognized not only by multiple publications but by the Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant Program, with a grant in 2013 for her writing about the house in and as contemporary art. Her voice has been a part of panel discussions and critiques at institutions including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Princeton University, UCLA, LAXART, and the Orange County Museum of Art.

Karapetian’s public art projects have been recognized by arts and civic organizations including the California Legislature Assembly (Certificate of Recognition 2015) and the City of Los Angeles (Certificate of Appreciation 2009.) She received support from the Wende Museum and Archive of the Cold War in Los Angeles in 2009 for her work with their collection and civic engagement program, and she received an allotment of an Artplace grant as funding for her participation in the Flint Public Art Project in Michigan in 2012.

Significant group exhibitions in which existing work has figured include The Wall in Our Heads: American Artists and the Berlin Wall, at the Goethe Institut, Washington DC, curated by Paul Farber in 2014; The Fifth Wall, at the Armory Center for the Arts, Pasadena, CA, curated by Irene Tsatsos, 2014; Prep School: Prepper & Survivalist Ideologies and Utopian/Dystopian Visions, at the Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA, curated by Max Presneill in 2014; Trouble With the Index, at the California Museum of Photography at UCR ARTSblock, Riverside, CA, curated by Joanna Szupinska-Myers in 2014; the Border Art Biennial 2010 at the El Paso Museum of Art and Centro Cultural Paso del Norte, El Paso, TX, and Juárez, MX, an exhibition juried by Rita Gonzalez and Itala Schmelz; and LA Confidential, at the Centre d’Art Contemporain, Parc Saint-Léger, France, curated by Sandra Patron and Allyson Spellacy in 2008. Karapetian realized a major new installation at the 2013 California-Pacific Triennial, at the Orange County Museum of Art in Newport Beach, CA, an exhibition curated by Dan Cameron.

Karapetian’s work is included in Charlotte Cotton’s survey of contemporary trends in fine art photography, Photography is Magic, published by Aperture in 2015, and has been reviewed in the LA Times, Artforum, Artcritical.com, and the artblog.org among many other publications. Profiles of the artist’s work have been published in, among other publications, Artforum.com, The Georgia Review, TATE Etc., FABRIK, Art LTD, and The San Francisco Chronicle, and her work has been discussed in the New York Times and Interview Magazine.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026