Dennis Darling: Holocaust Survivors

How does a photographer have the courage to document Holocaust survivors, especially when the photographer is an Irish Catholic from Upstate New York with no obvious common ground between self and subject? How does that artist gain the trust of those who have experienced unspeakable atrocities within their lifetime? And how do you ask someone to revisit a horrific memory? These are the questions I ask myself when considering Dennis Darling’s Holocaust Survivors.

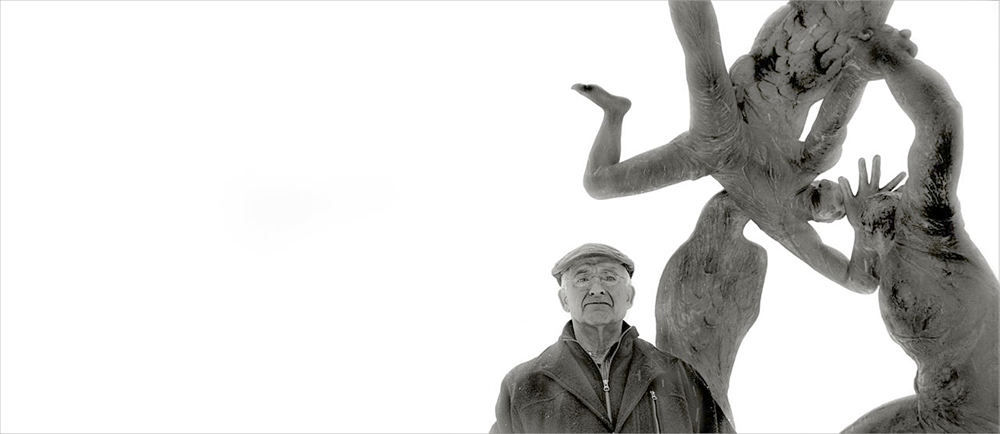

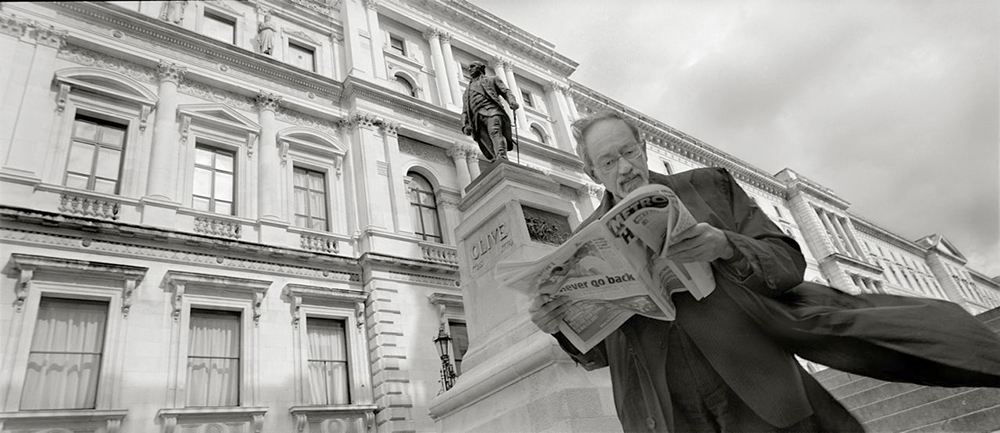

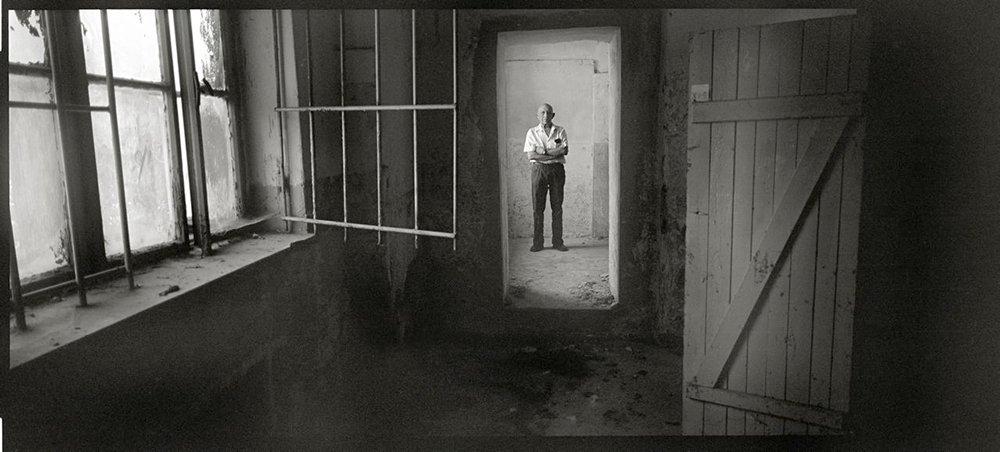

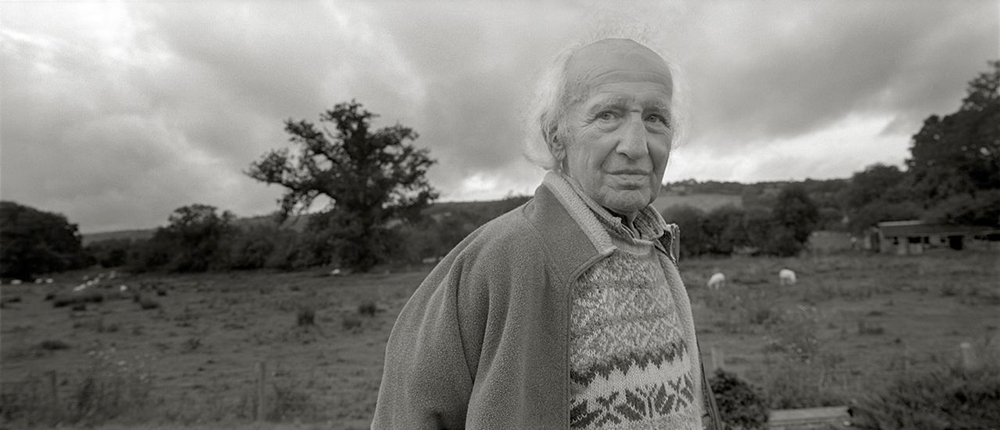

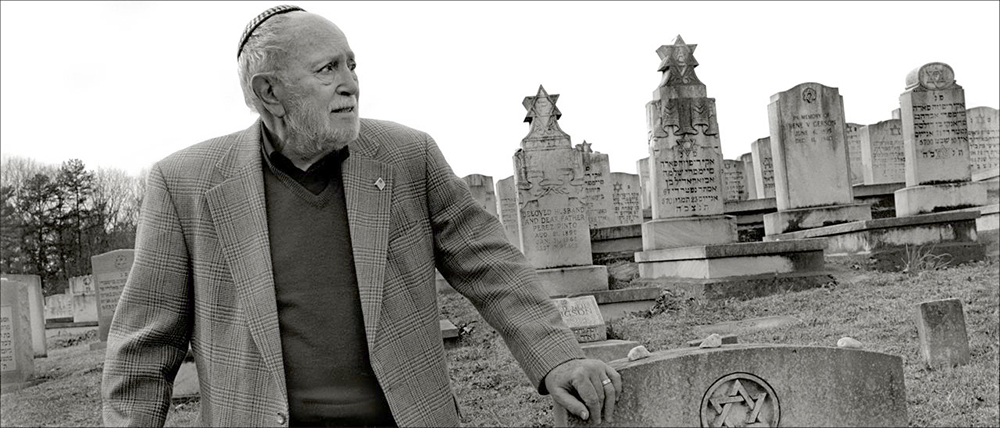

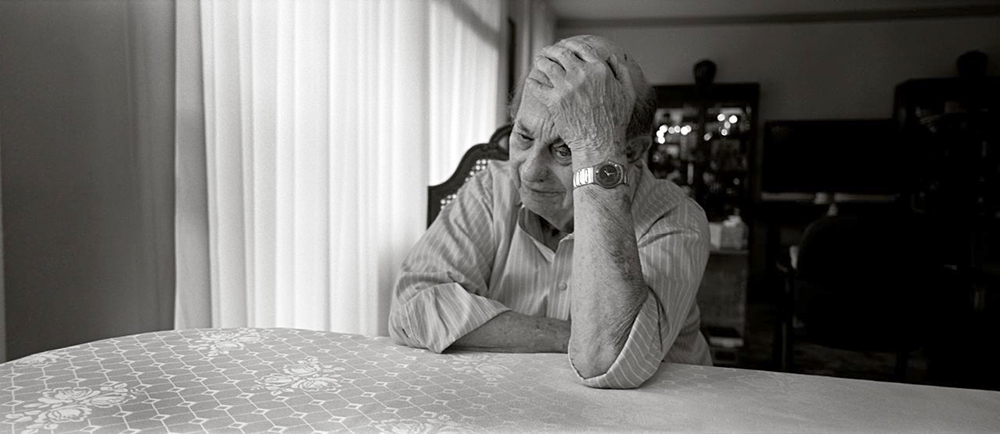

In 2012, Darling began photographing the aging and rapidly vanishing population of Holocaust survivors of Terezin, located north of Prague. Many of the Terezin imprisoned were awaiting transport to certain death at Auschwitz and other extermination camps. Since the beginning of his self-assigned series, Darling has photographed approximately 150 portraits in seven countries. His sitters are sometimes asked to accompany him to the location of the painful memory to make the picture. Many are photographed within personal spaces and against environmental backdrops that Darling uses to create an intimate and evocative portrait in a panoramic format. Each vulnerable face exposes a shared history of a horrendous past with a photographer sensitive to their experience. Darling captures a sense of “knowing” in the survivors; the images give life to virtues like honor, integrity, and courage in the expressions of the victims. They are not portraits of a defeated people, but rather, images of triumph.

Darling claims his surprise at the survivors’ willingness to be photographed; it surprises me as well. It makes a statement about their desire to be vulnerable for him in the name of history. It speaks about a photographer’s tenacity and determination to be a “keeper of the stories,” a trusted source to share truths with future generations. Darling has undertaken a profound and significant responsibility in the Holocaust Survivors project and exercises a quiet respectfulness in a portrayal of a persecuted people linked by brutalities of war for the necessity of history and humanity.

Dennis Darling holds a Master of Fine Arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a Bachelor of Visual Arts from Georgia State University. For the past 35 years, Darling has taught in the Visual Communication area of the School of Journalism at The University of Texas at Austin, where he directed the photojournalism area for more than a decade. His work has appeared national and international publications, resides in numerous private and public collections and has been exhibited in more than 150 exhibitions.

His most recent work in progress, Families Gone to Ash: portraits of survivors of the Nazi concentration camp at Terezin, was featured at The American Center, the gallery of the United States Embassy in Prague, Czech Republic.

Holocaust Survivors

The ranks of the generation that lived through the horrors of World War II is rapidly thinning. Within the next few years, all the people who have experienced the war’s seminal events will be gone. Living memory will cease to exist. In 2012 I began in an ongoing, self-assigned project to document the survivors of the Nazi concentration camp of Terezin, located just north of Prague. The camp was a way station for the death camps to the east; eighty-eight thousand inmates were transported from Terezin, most to their certain death.

When I first started the Terezin project I was timid about approaching the survivors to ask them to talk about their experience and to sit for a portrait. I found it hard to comprehend why they would be interested in speaking to a person from rural upstate New York, raised Irish Catholic and who, at the time, really couldn’t precisely express why he was interested in making their photograph. I was even more reluctant to ask those who lived in the vicinity of Terezin to accompany me for their portrait session to the place of such personal sorrow. Much to my surprise, nearly everyone I asked made that journey of forty miles and seventy years.

Sometime later, I happened upon an editorial in the New York Times that put precisely into words not only the reason for the Terezin survivors’ willingness to be a part of my project but, why I was compelled to attempt the series as well. In that editorial, the author and Holocaust survivor Samuel Pisar lamented, ‘that after 65 years, the last living survivors of the Holocaust are disappearing one by one,’ and he points out that at best, ‘only the impersonal voice of a researcher will soon be left to tell the Holocaust story’. At worst, he warns, it will be told in the “malevolent register of revisionists and falsifiers.” He cautions that this process has already begun. “This is why those of us who survived have a duty to transmit to mankind the memory of what we endured in body and soul, to tell our children that the fanaticism and violence that nearly destroyed our universe have the power to enflame theirs, too.”

Reliable sources estimated that only a few hundred Terezin inmates still survive to tell their stories. To date, I have made nearly 150 portraits, in seven countries. I am honored to have been the recipient of their trust and feel fortunate to have been able to make some of the last visual records of their unique histories. The last of living memory.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Tom Zimberoff: The White Fence and more..March 2nd, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch ExhibitionMarch 1st, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch Exhibition | Part IIMarch 1st, 2026