New Southern Photography at The Ogden Museum of Southern Art

On October 6th, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art’s largest photography exhibition to date, New Southern Photography, opens at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, LA and is on view until March 10, 2019. Curated by Ogden Museum of Southern Art Photography Curator, Richard McCabe, the exhibition will feature work (from the last 10 years) by 25 emerging, mid-career and established photographers: David Emitt Adams, Kael Alford, Elizabeth Bick, Christa Blackwood, John Chiara, Scott Dalton, Joshua Gibson, Maury Gortemiller, Alex Grabiec, Aaron Hardin, Courtney Johnson, Tommy Kha, Brittainy Lauback, Carl Martin, Jonathan Traviesa & Cristina Molina, Andrew Moore, Celestia Morgan, Nancy Newberry, RaMell Ross, Whitten Sabbatini, Jared Soares, Louviere + Vanessa and Susan Worsham. I’m turning the post over to Richard to share his thoughts and journey on bringing the exhibition to fruition. – Aline Smithson

©Alex Grabiec, A Landscape and the Terrace at Saint-Germain, Spring Archival Pigment Print 25 x 30 inches 2014

NEW SOUTHERN PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of the Twenty-First Century South

New Southern Photography was conceived in 2012 as a way to promote the superb photography being practiced in the twenty-first century American South. New Southern Photography highlights a new generation of emerging, mid-career and established artists who are making innovative and provocative work in and about the American South.

New Southern Photography features the camera-formed imagery of twenty-five photographers, filmmakers and video artists. The exhibition serves as a space for creating a conversation through the photographic arts about regional identity within the context of an interconnected and global world. New Southern Photography not only explores recent contributions the American South has made to international art through photography, but also serves as a platform to broaden the understanding and appreciation of a complicated, contested and often misunderstood place.

The American South is changing fast. Photographic technology is constantly evolving, and so are the stories Southerners are telling through photography. Today, Southerners have new stories to tell, stories as diverse as the region’s inhabitants. And even though the stories of the present may be different than those in the past, the Southern storytelling tradition of weaving tales about memory, place, land, family and history – some true and some not – remains central to the narrative of the region. – Richard McCabe, Curator of Photography, Ogden Museum of Southern Art

©Andrew Moore, Blue Sweep, Dallas County, AL Archival Pigment Print 42 x 72 inches 2017 Courtesy of Jackson Fine Art

©Andrew Moore, Zydeco Zinger, Abandoned Six Flags Theme Park, New Orleans Archival Pigment Print 50 x 60 inches 2012 Courtesy of Jackson Fine Art

Richard McCabe is a photographer, curator, and writer based in New Orleans. He was born in England and grew up in the American South. In 1998, he received an MFA in Studio Art from Florida State University. Since 2010, he has been the Curator of Photography at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art. He has organized and curated over twenty-five exhibitions including: Seeing Beyond the Ordinary, The Mythology of Florida, The Rising, Eudora Welty: Photographs from the 1930s – 40s, The Colourful South, and Self-Processing: Instant Photography.

Richard McCabe’s photographs have been included in gallery and museum exhibitions throughout the United States including: Size Matters, Mobile Museum of Art, Mobile, Alabama, Instant Joy, AM Richard Fine Art Gallery, Brooklyn, New York, and Once Around The Sun, Boyd/Satellite Gallery, New Orleans, Louisiana. In 2017, AINT – BAD press published LAND STAR, a monograph of McCabe’s photography. McCabe’s thoughts and writings on photography have been published in the New York Times, National Public Radio(NPR), Louisiana Cultural Vistas, Spot, The Bitter Southerner, AINT – BAD, and LENSCRATCH magazine. In 2016, he contributed an introduction essay for the Fall Line Press publication: Sweetheart Roller Skating Rink: Bill Yates.

The Reality on the Ground

The South is not monolithic. It is not black and white. There are many voices, many stories story to tell, and many storytellers at work. The South is as much Houston as it is the Mississippi Delta.

The South has been defined from without. Even the name implies a relationship to, and a differentiation from, the rest of America. And given that most of the borders of the world, excepting those carved by water, are as arbitrary as any line drawn by a toddler – the idea of the South is arbitrary as well.

Our region may be arbitrarily defined, but the created culture has imbued the South with meaning. The concentration of storytelling, of storytellers, has produced a living truth: creating narratives to move us through our lives is what Southerners do. And the photographers gathered here operate in that truth – some creating narratives in older veins, some adding new narratives to the mythical core of the South, and others refusing to have the visual world reduced to narrative.

All of these points of view are represented in the Ogden Museum of Southern Art’s permanent photography collection. The collection provides the template for New Southern Photography, and through the lens of the Ogden’s collection, the concept of New Southern Photography was born. The story of the South captured through photography, from 1864-present, can be traced through the Ogden collection of more than fourteen hundred photographs that highlight the depth and breadth of the American South’s contribution to national and international trends in photography.

Today, the once isolated South is fully engaged in a national and international conversation on art. Trade, human-migration, and the internet are all symbols of globalization and the inter-connectedness of the modern world. Mercedes-Benz, Hyundai, BMW, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Nissan automobiles are now manufactured in the American South. In recent years, domestic migration of people from across America and external migrations of people through immigration, have transformed the racial and cultural make-up of the South. In 2004, Texas became a majority-minority state. The internet connects the world by providing instantaneous news and content that erases borders in a form of virtual gentrification through information sharing.

As the South has changed socially, politically, and economically, Southern photography has evolved to reflect the values of the region. The ways photographs are made, viewed, and shared are in a constant state of reinvention. Throughout this technological evolution, remaining steadfast at the core of Southern photography is a strong storytelling tradition. The Southern storytelling tradition is the dominant thread that unites the work in New Southern Photography. Today, Southerners have new stories to tell, stories as diverse as the region’s inhabitants. Within the storytelling tradition, thematic motifs of place, time, memory, family, myth, reality, and loss resonate as much today as in the past.

Documentary is the most common form of photography practiced in New Southern Photography. Documentary – or documentary-style, a term coined by Walker Evans to describe photographs that blend artistic elements within the documentary tradition – takes on many variations, exploring multiple perspectives in contemporary Southern photography. Kael Alford and Scott Dalton, practice a straight documentary, photo-journalistic, or reportage form of photography as a way to confront some of the most pressing environmental and cultural issues of our time. Alford’s Bottom of Da Boot: Louisiana’s Disappearing Coast captures the unique indigenous communities of south Louisiana and the issues relating to climate change, migration, and land-loss due to coastal erosion. Alford’s work pays homage to Fonville Winans – who in the 1920s-40s photographed the people and places of Louisiana, focusing on Cajun culture of the French speaking Acadiana region of the state. Dalton’s Where the River Bends explores the relationship between El Paso, Texas and Cuidad Juarez, Mexico, and highlights the human costs of immigration, drug trafficking, and trade along the U.S. and Mexico border. Both photographers approach their subjects with an unblinking eye, capturing the human condition by creating provocative images that transcend the documentary tradition, infusing an artistic sensibility into luminous photographs that shed light on difficult issues facing the South and beyond.

Christa Blackwood, Girl Encaustic photogravure 37 x 37 inches 2013 Collection of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

Susan Worsham, Aaron Hardin, and Whitten Sabbatini apply a very personal approach to making documentary-style photographs. Following in the trajectory of Social Realism – found in Regionalist painting and photography from the 1920s-40s, as well as the street-photography and the snapshot aesthetic traditions of the 1960s-70s –Worsham, Hardin, and Sabbatini’s photographs are intuitive, subjective, metaphorical, and poetic. Their work provides a portal into lives filled with love, loss, memory, hope, and a search for meaning. By the Grace of God is Susan Worsham’s meditation on childhood memories, family, and her everyday life in Richmond, Virginia. Aaron Hardin’s The 13th Spring paints a story of family life through open-ended photographs filled with a subtext of Christian metaphors. Whitten Sabbitini’s Another Day in Paradise is a sentimental backward glance at the Mississippi Delta, a place where Sabbitini grew up, has since left, and now longs for.

Culture, race, and sexual identity within the context of the multi-cultural South is the focus of Tommy Kha, Celestial Morgan and RaMell Ross. Drawing inspiration from the social consciousness found in the work of photographers from the Depression-era Farm Security Administration (F.S.A.) through the Civil Rights movement, Kha, Morgan, and Ross address a broad spectrum of contemporary civil rights issues in a personal introspective way. Tommy Kha’s A Real Imitation looks at cultural and sexual identity through self-portraiture within the context of his hometown of Memphis, Tennessee. Celestia Morgan’s Redline addresses systematic racial bias found in housing practices in her native Birmingham, Alabama.

©Courtney Johnson, Ocean Isle Beach Pier, 2012 Pigment print from underwater pinhole camera 32×40 inches

©Courtney Johnson, Oceanana Fishing Pier, 2012 Pigment print from underwater pinhole camera 32×40 inches

As an outsider looking in, RaMell Ross explores iconic Hale County through the lens of otherness and blackness in his series South County, AL (A Hale County). Kha, Morgan and Ross bring the continued struggle of civil rights into the present through their own personal history and visual language.

Southern history and culture are ripe with myths and legends. Tales told and retold over centuries have helped form a shared cultural identity and regional consciousness. The camera is a machine made for exact replication of the world; this objective mirror of reality sometimes runs counter to the romantic portrayal of the American South in art and literature. Surrealism, an international art movement popular in the 1920s-30s was an artistic style particularly adept at capturing the romanticism found in Southern literature, folklore and history. Surrealism was pioneered and practiced in 1930s-40s New Orleans by photographer Clarence John Laughlin. Laughlin merged elements found in surrealism into the documentary tradition to produce dreamlike imagery, forming a subjective visual representation of the mythical Old South. Laughlin’s masterpiece, Ghosts Along the Mississippi a book published in 1948, featured photographs of Louisiana plantation architecture. In, New Southern Photography Nancy Newberry, Maury Gortemiller, Cristina Molina and Jonathan Traviesa combine personal narrative with elements of surrealism and the documentary tradition in their photographs, which are constructed to address the myths and legends of the South.

©David Emitt Adams, Chalmette Refining No.1, New Orleans, LA Wet-plate Collodion on 55 gallon barrel lid 23.5 inches in diameter 2018

©David Emitt Adams, Valero Bill Greehey Refinery No.2, Corpus Christi, TX Wet-plate Collodion on 55 gallon barrel lid 23.5 inches in diameter 2018

Newberry’s Smoke Bombs and Border Crossings confronts the history of her native state of Texas. Within her theatrical photographs, struggles between competing cultural and racial forces – American settlers, Mexicans, cowboys and Native Americans – act out roles in a play based on the colonization and formation of the Lone Star State. Gortemiller’s wildly strange Do the Priest in Different Voices is a visual manifestation of biblical text set in the holy lands of the modern American South. Verses of the bible are re-constructed and interpreted in the camera and computer by Gortemiller, and placed in a contemporary context as a way to understand and make sense of his personal history in relation to the word of God. Husband and wife team, Cristina Molina and Jonathan Traviesa investigate the myths of Florida in Sad Tropics. The Sunshine State is steeped in myths and fables, and for centuries has been portrayed in art and literature as an Earthly Eden filled with crystal clear artesian springs promising eternal youth. Florida, as portrayed in Sad Tropics, has disintegrated into a Paradise Lost in the form of a tacky tourist trap.

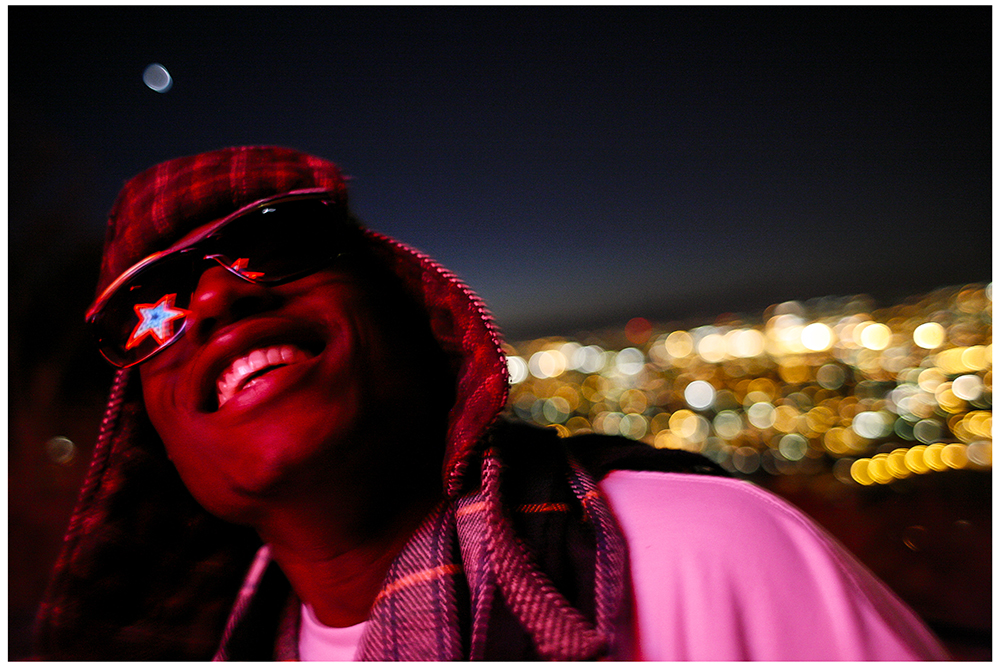

One of the finest expressions of the Southern storytelling tradition is through music. The South is the birthplace of jazz, blues, bluegrass, country, and rock-n-roll. Music has long been rich subject matter in Southern photography. In the 1980s-90s, Birney Imes continued the groundbreaking use of color photography introduced to mainstream art by Southern photographers William Eggleston and William Christenberry in the 1960s-70s. In Juke Joint, Imes photographed the energy and gestalt of the vanishing culture surrounding African American blues music, focusing on the unique vernacular architecture of the Mississippi Delta. As one musical style fades from popularity, another ascends to take its place. Today, Hip-hop is king, and represents the most popular form of music on the planet. Jared Soares’ Small Town Hip-hop offers a peek into the lives of local DJs and aspiring rappers in a behind-the-scenes look at hip-hop culture in the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia. In Athens, Georgia, Brittany Lauback employs her skills as a still-photographer in directing Transparent Lines, a music video for the band Elf Power. Transparent Lines is a psychedelic mash-up of song and dance, featuring an Appalachian folk dancer clogging to the sounds of hypnotic alternative rock.

©Elizabeth Bick, Street Ballet VI Location: New York, NY Archival Inkjet Print 40 x 60 inches 2016 Elizabeth

©Elizabeth Bick Street Ballet XIII Location: Houston, TX Archival Inkjet Print 40 x 60 inches 2018 Jared Soares Oxy Neutron and the Star Archival Pigment Print 16 x 24 inches 2009

Many contemporary photographers choose to re-imagine and expand upon the documentary tradition by deconstructing and reconstructing photographic imagery in the camera and computer. Others manipulate the surface of the photographic print in the studio with collage, paint, and varnish – an additive process found in the practice of painting. This type of cross-pollination of media expands the parameters of photographic imagery, and resonates throughout the work in New Southern Photography. By reimagining the traditional genres of landscape, portraiture, and still life – and through synthesizing formal concepts and methodologies from the history of painting and sculpture – a new photo-prototype is created that transcends the idea of photographic purity.

The landscape is the physical embodiment of a place or region. In art the landscape can be symbolic of a regional or national identity. In the early 2000s, Virginia native Sally Mann produced Deep South, a selection of black-and-white photographs of the lush Southern landscape that pays homage to the romantic depictions of the South throughout art history. Her radiant and atmospheric images are visual manifestations of her love of place and familial ties to the land.

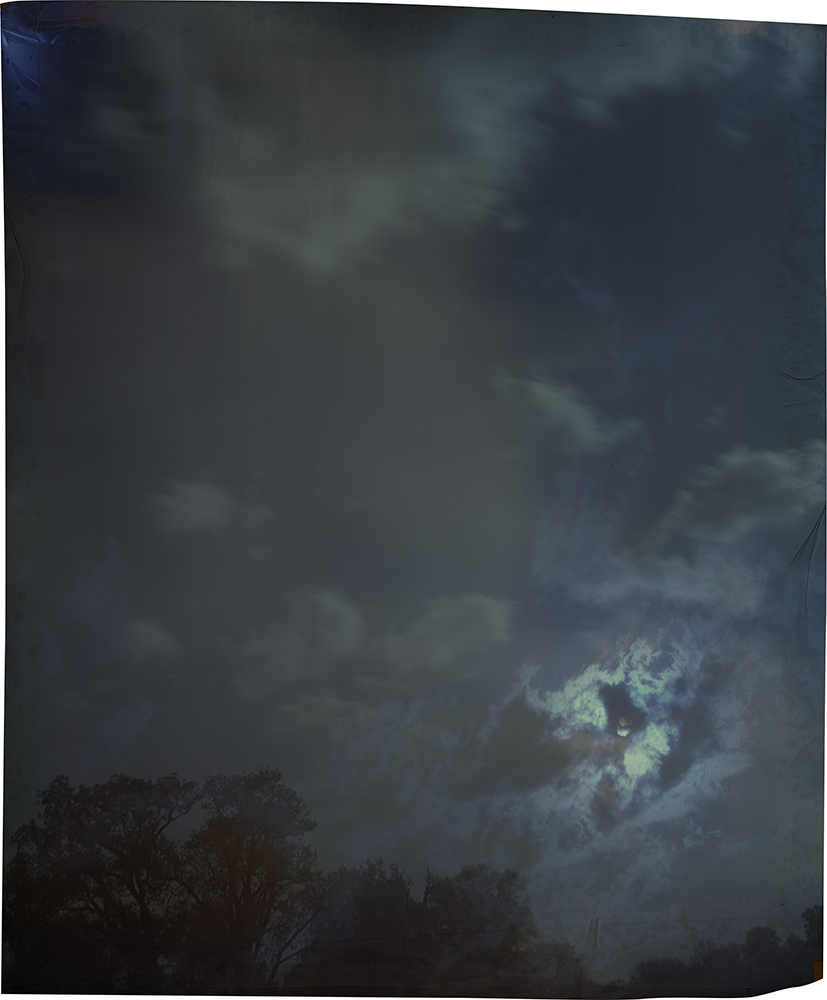

Within contemporary Southern photography, the romantic pictorialist language of the landscape tradition is expanded upon through process, theory, and ultimately aesthetics. The photographs by David Emitt Adams, Andrew Moore, and Alec Grabiec focus on the built environment and the rural, suburban, and industrial landscape. Adams’ Power documents the complex network and systems that facilitate the oil and energy industries. Power plants, refineries, and tanker ships are featured in Adams’ tintypes that meld 19th century processes within a contemporary sculptural context. Moore’s Southern Photographs concentrate on urban and rural centers that are in stages of transition from the effects of social, political and economic upheaval and change. Grabiec’s Back East investigates the in-between spaces, the landscape of the hinterlands – an area of non-descript borders and blurred demarcation that separates urban, rural, and suburban spaces.

Christa Blackwood and John Chiara employ 19th century photo processes and technologies to document the natural landscape. These photographs pay homage to and invert the Western landscape tradition practiced by Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. Blackwood’s Naked Lady: A Red Dot rearranges the perspective of the female nude in the Western landscape through the feminine gaze. Chiara’s Mississippi features unique pinhole photographs that abstract the flatlands of the Delta region into luminous, painterly, and surreal one-of-a-kind images. Filmmaker Joshua Gibson’s hand-processed 35mm film, The Kudzu Vine, weaves a Southern Gothic tale on the history of kudzu. Known as the plant that devoured the South – kudzu, an invasive non-native vine imported from Japan – has ironically become a synonymous symbol of the modern Southern landscape.

©John Chiara, Oakhurst Road at Payne Road V1 33.5 x 28.25 inches lfochrome paper, unique photograph 2018 Courtesy of Jackson Fine Art

©John Chiara, Old River Road, Levee Road, Horn Lake Landing 33.5 x 28.25 inches Ilfochrome paper, unique photograph 2018 Courtesy of ROSEGALLERY

Street photography was all the rage in the art photography of the 1960s-70s. Lyle Bonge, perhaps, best interpreted street photography in the mid-1960s South with The Sleep of Reason, a series featuring grainy black-and-white photographs of New Orleans Mardi Gras in the Vieux Carre. In the early 2000s, Alec Soth rose to superstardom with his series, Sleeping by the Mississippi. While traveling the length of the Mississippi river from its headwaters in the upper Midwest to the Gulf of Mexico, Soth created a body of work that introduced the world to his deadpan street-portraiture style mixed with landscape and still life images. Bonge and Soths’ personal documentary styles of street photography are recontexualized and expanded upon in New Southern Photography by the works of Elizabeth Bick and Carl Martin. Bick’s Street Ballet is a choreographed exercise in urban theater. Detached and clinical, Street Ballet is the complete opposite of the personalized street work practiced in the past. Martin’s Public Gesture explores the relationship between humans and the built environment. Public Gesture is a playful investigation into the influence of architecture and material commodity on the human condition.

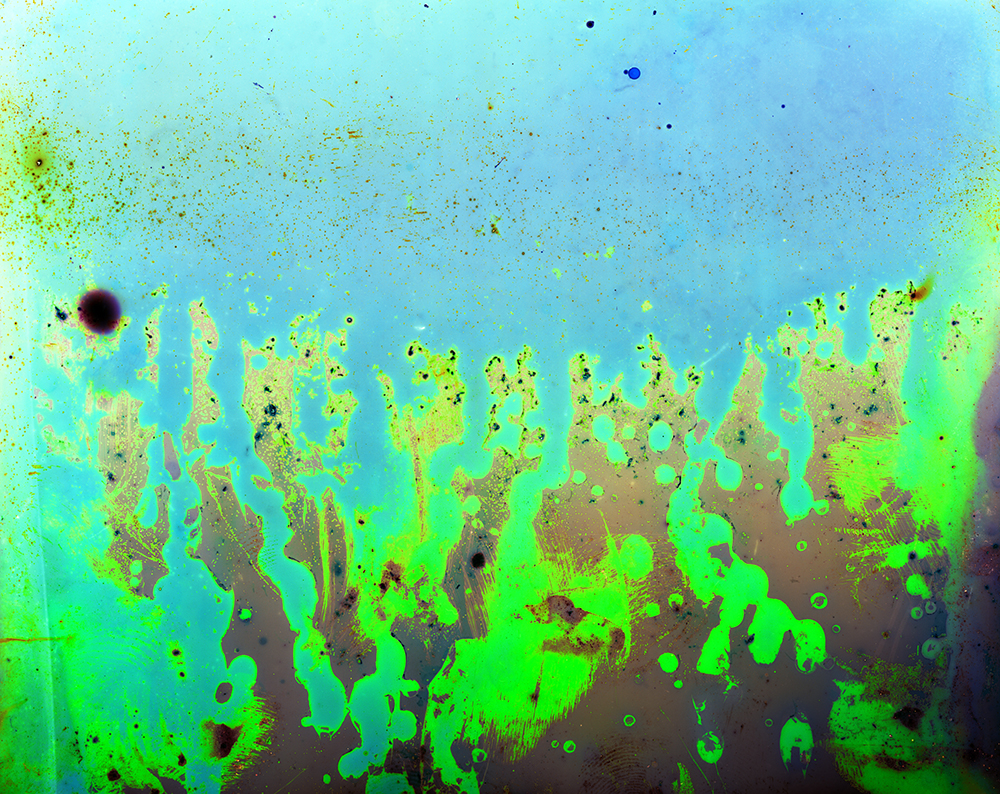

Experiments in abstraction are at the heart of the work of Louviere + Vanessa and Courtney Johnson. Both use the camera to produce images that are much more aligned with Abstract Expressionism found in painting than with the realism of straight objective photography. Abstraction in Southern photography found a champion in 1930s-50s New Orleans with photographer Clarence John Laughlin. Laughlin’s style varied from documentary and surrealism to complete abstraction. Today, New Orleans husband and wife team, Louviere + Vanessa, take abstraction to the extreme by making visible the invisible in Resonantia – a photographic depiction of sound waves. Each photograph in the Resonantia series captures a musical note found within the musical scale, resulting in imagery that is amorphic, dark, and mysterious. Johnson’s Light Lure features underwater photographs – captured by a hand-made pinhole camera – that have the appearance of soft-edge watercolors. Incorporating chance through blending science with art, Light Lure’s lo-fi images are examples of pure color abstraction.

©Jonathan Traviesa & Cristina Molina, Image from Sad Tropics Archival Pigment Print Size Is Variable 2016

©Jonathan Traviesa & Cristina Molina, Image from Sad Tropics Archival Pigment Print Size Is Variable 2016

At the beginning of the 21st century the identity of the American South and the definition of Regionalism are in flux. Old South, Antebellum South, and New South were all terms to used to define the region at certain points in history. The South today is situated in a place where Regionalism and globalism are connected. Southern art today is engaged in a two-way conversation, radiating out from the American South to the world, while at the same time, the world radiates back to the South. The goal of New Southern Photography is to present art that truly reflects the region from which it was made. In One Writer’s Beginnings, writing about her early life as an aspiring photographer in 1930s Mississippi, Eudora Welty states, “The camera was a hand-held auxiliary of wanting-to-know.” This view of the camera as a way to investigate the world and make sense of one’s world resonates within all of the work in New Southern Photography.

Photography has now eclipsed the popularity of painting and sculpture within the pantheon of fine art. Photography is ubiquitous, and everyone seems to be a photographer via selfie-sticks and smart phones. Within the photographic arts in the American South, there exists a really wonderful problem for curators – there is almost too much interesting and diverse photography being made.

New Southern Photography is not intended to define the South or Southern photography, but rather to create an open discussion. This exhibition seeks to broaden the conversation about Southerness by balancing myth and reality while expanding the previously held notions of the region through photography. The twenty-five photographers and filmmakers included in New Southern Photography portray a vision of the region that is informed by the past, grounded in the present, and through innovation, expands the dialogue of photography in the South into the future. – Richard McCabe

©Kael Alford, Edison Dardar Jr. casting for shrimp, Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana Archival Pigment Print 14 x 14 inches 2010

©Kael Alford, Joseph and Jasmon Jackson play in the bayou, Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana Archival Pigment Print 14 x 14 inches 2010

©Louviere + Vanessa, Spectrograms from all 12 photographs of sound Mixed Media – Archival pigment print on Kozo paper, gold leaf and resin 16 x 16 inches 2016

©Maury Gortemiller, Then They Took the Body and Wound It in Linen Cloths with Spices Archival Pigment Print 2012

©Maury Gortemiller, They Will Be Punished with Everlasting Destruction Archival Pigment Print 24 x 36 inches 2012 Nancy

©Scott Dalton, Cotton Candy, Ciudad Juárez, Mexico Archival Pigment Print 20 x 20 inches Edition 1 of 6 2010

©Scott Dalton, Lucha Libre Living Room, El Paso, TX Archival Pigment Print 20 x 20 inches Edition 1 of 6 2011

©Susan Worsham, Marine, Hotel Near Airport, Richmond, Virginia Archival Pigment Print 32 x 40 inches 2009 Collection of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

About the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

Located in the vibrant Warehouse Arts District of downtown New Orleans, Louisiana, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art holds the largest and most comprehensive collection of Southern art and is recognized for its original exhibitions, public events and educational programs which examine the development of visual art alongside Southern traditions of music, literature and culinary heritage to provide a comprehensive story of the South. Established in 1999 and in Stephen Goldring Hall since 2003, the Museum welcomes almost 85,000 visitors annually, and attracts diverse audiences through its broad range of programming including exhibitions, lectures, film screenings and concerts which are all part of its mission to broaden the knowledge, understanding, interpretation and appreciation of the visual arts and culture of the American South.

The Ogden Museum is open daily from 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. with extended hours on Thursdays from 6 – 8 p.m. for Ogden After Hours. Admission is free to Museum Members and $13.50 for adults, $11 for seniors 65 and older, $6.75 for children ages 5-17 and free for children under 5.

The Ogden Museum is free to Louisiana Residents on Thursdays from 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. courtesy of The Helis Foundation. The Helis Foundation is a Louisiana private foundation, established by the William Helis Family. The Art Funds of the Helis Foundation advance access to the arts for the community through contributions that sustain operations for, provide free admission to, acquire works of art and underwrite major exhibitions and projects of institutions within the Greater New Orleans area.

The Museum is closed Lundi Gras and Mardi Gras, Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day and New Years Day.

The Museum is located at 925 Camp Street, New Orleans Louisiana 70130. For more information visit ogdenmuseum.org or call 504.539.9650.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and Photography, Part 2January 22nd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and PhotographyJanuary 21st, 2026