Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South, Day 6

In addition to an amazing curation of Southern photography and writing, Southbound also features an incredible interactive map depicting concentrations of everything from African Americans to chickens, confederate symbols to field crops, as well as an “Index of Southernness”. This index was created by fusing the other maps presented, showcasing “classic regional geographic patterns of core, domain, and sphere, where places that read as most Southern are readily identifiable.” According to the curators, “In representing places where southerness is most intense, the Index reveals the resilience of the region. By also showing how southerness transitions across space, the map weaves a rich regional tapestry.”

The maps were created by Dr. Rick Bunch at the University of North Carolina Greensboro, using publicly available datasets from the United States Census Bureau, the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the United States Agricultural Census, among other sources.

It’s fascinating to view these maps and ponder the counties and communities where the images in the Southbound project were made. To visualize Jessica Ingram’s photograph of Medgar Evers’s Backyard in Jackson, Mississippi in the context of the deep red concentration of Confederate Monuments mapped in that county. Or to see that the high to medium characterizations of “southernness” mapped in the index stretches North throughout all of Virginia, through Maryland and Deleware, and into southern Pennsylvania and New Jersey – places that might not be instinctively characterized as Southern. You could come to 50 different conclusions about what exactly Southernness means as an identity and culture as you click through these various maps – and perhaps that’s precisely the point.

Curating the Map – Mark Sloan and Mark Long

Geographers, whose discipline is perhaps most closely associated with maps as tools to communicate ideas about the world, are the first to recognize the limitations of those maps. For all the power that we vest in them, maps suffer the shortcomings of the cartographer’s competence, intent, and perspective, and they are dated even before they go to press.[i] Like all representations, their meaning is not necessarily self-evident, labels and keys notwithstanding, and, ultimately, cannot be disentangled from their contexts. No one would argue that maps made by colonial surveyors or indigenous shamans are one and the same, nor that they meant the same things to viewers when they were made as when revisited decades or centuries later. Introductory college-geography courses glory in confronting students with map projections that underline how outlandishly enormous Alaska is on the time-honored Mercator map (however ideal it is for navigation); in showcasing the purported “upside-down” map of the world with the Southern Hemisphere at the top of the globe; or in using Pacific-centered maps to confront the ethnocentrism of a world anchored by the Atlantic Ocean, emblazoned into our consciousness by European cartographers from the sixteenth century onward.

[i] J. B. Harley, “Deconstructing the Map,” Cartographica 26, no. 2 (Spring 1989), 1–20.

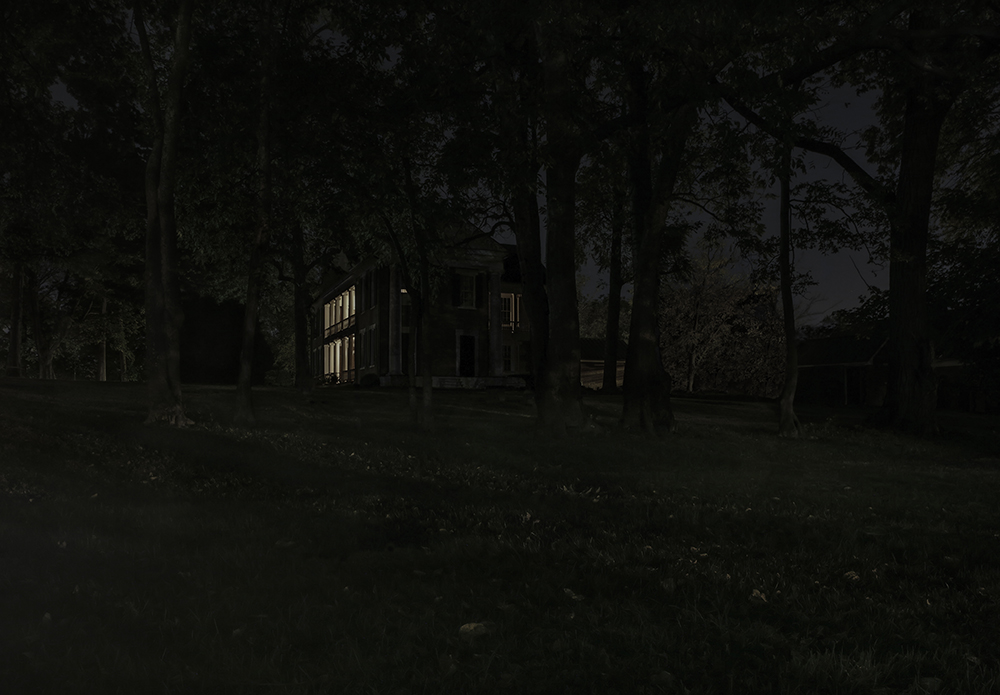

Keep Going, 2014. From the Through Darkness to Light: Photographs along on the Underground Railroad series. Crossing the Tennessee River, Colbert County, Alabama © Jeanine Michna-Bales

Hidden in Plain Sight, 2014. From the Through Darkness to Light: Photographs along on the Underground Railroad series. Rose Mont Plantation, Sumner County, Tennessee © Jeanine Michna-Bales

Maps then, like photographs, for all the authority we confer on them, present us with imperfect renditions of places. So it must be, too, with Southbound’s map of the South, which could be more accurately called an index of Southerness in that its maps track historical, economic, religious, demographic, commercial, and cultural indicators. It affords us a more traditional cartography with which to parallel the images of the South that congeal through encounters with the Southbound photographs. Just as with those images, viewers have some latitude in configuring their experience through selection of the markers they prize most in defining the region. That is achieved through successively switching layers on and off in a digital mapping environment, available to viewers of Southbound in the exhibition space or on the project’s micro-website (southboundproject.org). The multiplicity of maps of the region available there can be overlaid to create our Index of Southerness, in which indicators intrinsic to the region, like religion, race, or the memorialization of one people’s vision of history there, can be weighted to reflect that fact.

The Index incorporates multiple maps that are generated from the querying of many databases, from the census to commercial datasets to datasets of school and street names countrywide. Some of the maps seem to transpose markers such as census counts of race more or less directly to the Index, yet they are heavily processed; thus, our map of race measures the clustering of populations by county, suggestive of longer term patterns of habitation rather than a mere snapshot of distribution. The maps that make up the Index required extensive processing to discover places all the way across the United States where, for example, Confederate generals are memorialized in the landscape in street, school, and library names; the same can be seen in the names of civil rights activists or synonyms for the region like magnolia or Dixie. The cleaned-up street-name dataset alone contains almost nine million records and was queried using more than six hundred search terms. The resulting map of counties countrywide, of variables from street and business names to Civil War monuments to magazine subscribers to students’ vernacular maps, all make the region we call the South clearly visible.

Vatos (Homeboys), 2008. From the Durham Stories: Not Hell But You Can See It From Here! series. Durham, North Carolina © Titus Brooks Heagins

Geographers understand that regions are dynamic, always in flux, always emergent. They also recognize, however, that there are places where the aggregate of regional culture resonates most fully, a core, where, in this case Southerness, however defined, endures. One vernacular region that might equate to the Index’s core is the so-called Deep South. This is a place associated with particular histories, a multiplicity of accents all patently Southern, a constellation of foods and drinks that, as we learn and relearn, all taste of the South, where rural ways of living reigned longer, among many other indicators. Around that core is found a domain where maps underline the dominance of the cultural attributes under consideration, even as their intensity declines. Distance decay accounts for further decline across space so that such cultural markers are less prevalent but still present in the larger sphere.

Our mapping of the South showcases just such patterns of core, domain, and sphere. Further, mapping at the county scale calls into question the all-too-convenient cartography of the South following state lines. If history were all that mattered in defining the region, then state boundaries might make sense, but if we understand the South as multifaceted, then indicators such as religion, historical markers, and business names transition across space.

As a deer pants for flowing streams, so pants my soul for you, O God, 2015. From the What’s Lost Is Found series. Hale County, Alabama © Lauren Henkin

The life of the flesh is in the blood, 2015. From the What’s Lost Is Found series. Hale County, Alabama © Lauren Henkin

The Index maps also show other parts of the United States where indicators associated with the region are to be found. The magnolia, for many a quintessentially Southern tree, can be mapped readily in street and cemetery names all through the South, for example, but there are many places outside the region where it is also to be found, southern California for one. The construction of the Dixie Highway network, running north–south to connect the South and the Midwest, just when monuments to Confederate heroes were inscribing a menacing vision of history into the Southern landscape, serves today to pull places in Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana partly into our digital map of the region. The term Dixie, moreover, would have caught the eye every bit as much in the Midwest as it did in the erstwhile Confederate states, more so for African Americans.

Mapping the entirety of the country at the county scale creates a rich tapestry of markers all across the United States. It underlines commonalities throughout the territory but serves, too, to highlight the South. Viewers of Southbound can use the Index of Southerness to puzzle over their own visions of the region by combining indicators from the demographic to the commercial to the historical, to take several examples. As is the case in viewing the exhibition, catalogue, and website photographs of and about the region—the Index provides a platform from which to reengage with this place.

Medgar Evers’s Backyard, Jackson, Mississippi, 2007. From the Road Through Midnight: A Civil Rights Memorial series Jackson, Mississippi. © Jessica Ingram. On June 12, in 1963, Medgar Evers, the NAACP’s first field secretary in Mississippi, was gunned down in his driveway in Jackson. Byron De La Beckwith was tried for the murder in 1963 and 1964; both trials ended in hung juries. De La Beckwith was convicted with new evidence in 1994.

Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial Carving, Stone Mountain, Georgia, 2006. From the Road Through Midnight: A Civil Rights Memorial series. Stone Mountain, Georgia. © Jessica Ingram. Gutzon Borglum, who would go on to create Mount Rushmore, was an activemember of the Ku Klux Klan when he began his carving on Stone Mountain in 1923. Borglum’s work was destroyed after he got into a dispute with the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association, and a new carving was begun by Augustus Lukeman. The monument, which depicts Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis, wasn’t completed until 1972.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Riley Goodman: Art + History Competition Honorable Mention WinnerApril 4th, 2025

-

Oleksandr Rupeta: Art + History Competition Second Place WinnerApril 1st, 2025

-

Jared Ragland: Art + History Competition First Place WinnerMarch 31st, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Researching Long-Term Projects with Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-KilroyMarch 27th, 2025