Mary Beth Meehan: Seeing Newnan

©Mary Beth Meehan, Cliff and Monique Cliff and Monique, the President and Vice President of the African-American Alliance in Newnan Georgia, are photographed at the Farmer Street Cemetery. The unmarked land is thought to be the largest slave cemetery in the South

All Installation Views are from Newnan, Georgia, April 2019. The banners will be up for one year.

Over the years, Mary Beth Meehan has used her photography to tell stories, to spark conversation, and to celebrate those who are often overlooked or unseen…on a big scale. Her new project, Seeing Newnan, began as a two-week artist’s residency in a town an hour south of Atlanta. She spent the next two years working to understand Newnan’s history and people through a process of collaborative portraiture, photographing and hearing the stories of numerous residents.

“Her photographs include members of the white, black, Latino, Muslim, wealthy, and working-class communities – a mix of everyday people. As the massive portraits were being installed in Spring of 2019 on the outside walls of buildings, conversation and controversy erupted – among neighbors and on social media – about Who Represents Newnan.

By exhibiting her intimate portraits on a celebrity scale, Meehan has jolted people to examine their preconceptions. The installation will remain in place for one year, providing a springboard for public engagement and serious dialogue – which has already begun. Newnanites are deciding what matters most to them about such issues as race, religion, ethnicity, inclusiveness and diversity.”

Mary Beth has created a blog titled ReSeeing that shares the stories of her participants and the reactions to their public portraiture. “Seeing Newnan” was made possible with generous support from the School of the Arts at the University of West Georgia and the Hollis Trust.

Mary Beth Meehan is an independent photographer and educator, most recently known for her large-scale public installation work. Over the past twenty-five years, Meehan has focused on questions of visibility and social equity, embedding herself in communities across the United States, including in post-industrial New England, the American South, and in Silicon Valley, CA. Meehan lives in New England, and has held residencies at Stanford University, the University of Missouri School of Journalism and at the University of West Georgia. Her most recent portrait banner project, “Seeing Newnan,” installed in April of 2019, has sparked community-wide conversations among residents of a small Georgia town regarding such issues as identity, history, ethnicity, religion, inclusion, and race.

Mary Beth has lectured and led workshops at the School of Visual Arts, New York, the Rhode Island School of Design, and the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, in Boston. A former staff photographer at The Providence Journal, her photojournalism work has been published in the New York Times, The Boston Globe, Le Monde, and other publications in France, Germany, China and Japan. Her first photography book, Visages de Silicon Valley, was published by C&F Editions in France in 2018; the English edition is due to be published next year.

Mary Beth received a Bachelor of Arts degree in English at Amherst College, and a Master of Arts degree in photojournalism at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

©Mary Beth Meehan, Trent: Trent graduated from Newnan High School as a member of ROTC before joining the U.S. Army. He served for one year in South Korea, before being stationed in El Paso, Texas.

©Mary Beth Meehan, Trent installed: Trent graduated from Newnan High School as a member of ROTC before joining the U.S. Army. He served for one year in South Korea, before being stationed in El Paso, Texas.

Seeing Newman

I was invited to photograph the people of Newnan, Georgia, by the head of a local artists residency, who had seen my banner portraits in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. He told me he felt that he and other residents of the town lived in their “little isolated bubbles,” and that my portrayal of a community had the power to pierce those bubbles. After many emails, conversations, and a visit to Newnan, I began photographing in November of 2016.

For 25 years I’ve been working in communities – trying to understand them as ecosystems influenced by history, industry, politics, migration, and race. I try to look deeply into the dominant narratives of those communities, and consider the ways in which people’s experiences are or are not represented in those narratives. What I’ve learned is that we Americans do indeed live inside our bubbles, rarely challenging our first impressions or traveling outside our experiences to consider those of someone different from ourselves. As a result of this isolation we’ve developed many bad habits: We lead with our preconceptions; we dwell on the surface of things; we think we know what we see.

After I’d hung my first set of blown-up portraits, on public buildings in my hometown of Brockton, Massachusetts, I realized that I could make the viewers interact with a place that I loved – despite its image as a place of severe dysfunction and crime. I understood the resentment between the old-timers – descendants of European immigrants – and the newcomers, immigrants of color from all over the developing world. I tried to make the connection for my Irish-American father, for example, between his Irish grandmother and a Cape Verdean woman, new to his city but struggling to feed her young family, just as his grandmother had done.

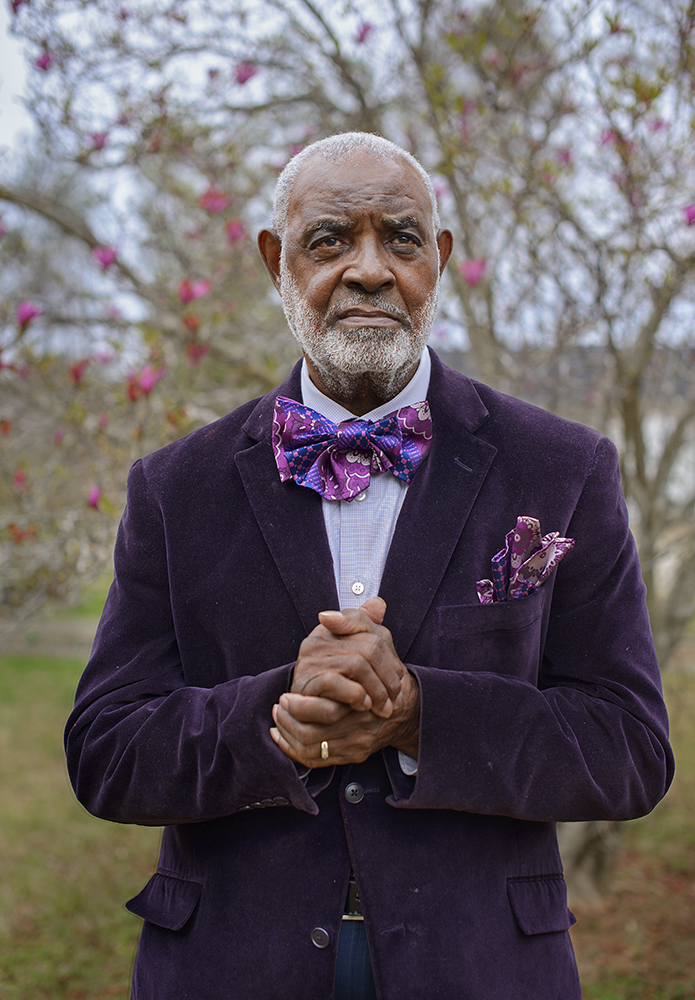

©Mary Beth Meehan, Rufus: Rev. Rufus is a local pastor and member of the Newnan community. He lives on the land his family has owned for generations; the road is named after his father.

In Providence, Rhode Island, I continued this work with straightforward portraits, which leveled a direct gaze to invite the viewer into the many worlds of this city’s people: an auto mechanic from Guatemala, an Irish-American mother nursing her baby, a bus driver from Haiti.

Before my invitation to portray the Southern city of Newnan, I had mostly worked in my native New England, a region that I felt I understood intimately. In the South, I was presented with a new challenge: the need to get beyond my simplistic understanding – one informed largely by the media and my prejudices – and arrive at a deeper, more nuanced understanding.

To that end, I have developed a process that I’ve come to rely on: of moving slowly, of asking many questions, of talking – and listening – as I try to hear things from people’s many perspectives. I try to consider the long threads of history: how they come together to weave the present moment, tethering the present to the past. And I try to replace the impulse to judge with a more spacious one: to understand how things came to be the way they are.

©Mary Beth Meehan, Kristina: Kristina proudly displays her Confederate flag from her porch in Grantville. To her, the controversial symbol is instead a symbol of evolution, hope, and peace.

Meanwhile, photographs of ordinary people on a celebrity scale – giant banners hanging in the public square – turns out to have radical effects: People are startled by them, disoriented. They are prompted to ask questions – Who is that? Why is she important enough to be up there? What is his story? With these questions, which we rarely ask of the strangers around us, viewers are given an opportunity to see their prejudices as they arise, and examine them.

By installing my portrait banners in a community’s built environment, I have a chance to symbolically disrupt the power structure – the hierarchy of public visibility – that has come to define that community. So, in Georgia, portraits of an African-American woman who came of age under Jim Crow, a wealthy descendant of a cotton mill owner, a poor mill worker, and a recent Mexican immigrant are calling out now to be seen across a level visual field – one in which they make an equal contribution to the life of the town, regardless of how they have been depicted in the past.

The writing on my blog, “ReSeeing,” presents my process of moving through a community and reflecting on my own preconceptions and shifts in consciousness. In this way, I’ve been able to relate something of the people who have worked with me, as well as how their individual experiences have been shaped by history.

I want my work to open up new possibilities for connections, new opportunities for people to find common ground with each another. I want to show what it looks like when we just slow down, make space for people who are different than we are, ask questions, and listen.

©Mary Beth Meehan, Zahraw and Aatika: Zahraw and Aatika were born in Georgia, and have lived their whole life in Newnan. At Northgate High School they both belonged to the National Honor Society (Zahraw was the president), the Beta Club (Aatika was president), the Spanish Honors Society, and the Key Club. Zahraw now goes to Georgia Tech; Aatika to Georgia State.

Initial Community Response to Newnan Project

In Newnan, when “Zahraw and Aatika,” a portrait of two young Muslim women, was installed, the greater community’s initial reaction to the photograph was fierce. In phone calls to the University of West Georgia and the Newnan Times Herald, in private conversations, and on social media, a very vocal group of people stated their rejection of any depiction of Islam within their community, and demanded that the photograph be taken down. On Facebook, the conversation veered into anti-Muslim stereotypes, images of the American flag, calls for the terrorist acts of 9/11 to be avenged, and for Trump to be reelected in 2020.

Yet even more vocal and numerous were the voices in Newnan intent on defending the young women: upstanding citizens born in the county, members of the National Honor Society, college students. In response to one Facebook comment alone– which garnered some 1,100 replies –– people of various religious and political persuasions called for a common decency, and also articulated their beliefs in such things as the First Amendment, religious tolerance and freedom, and the tenet of Christianity to “treat one’s neighbor as thyself.”

I’ve been told since the initial installation that the conversations in Newnan are continuing – that new friendships have been made, that debates are taking place in barber shops and grocery stories, and that Newnanites plan to use the work in formal conversations and panels throughout the year of the installation to move forward the notion of an inclusive community. I hope that people will trust one another enough to delve into the places that need to be healed, and I would be very proud if my work helped that to happen.

©Mary Beth Meehan, MacDonald: MacDonald attends Cotillion, a southern tradition of etiquette and dance training, as did his father three decades ago.

©Mary Beth Meehan, Brittany: Brittany, a native of Texas, moved to Newnan when she met her husband. She works at the University of West Georgia, and is a member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority – the oldest sorority for African-American college women in the country.

©Mary Beth Meehan, Ariel: Ariel attends Cotillion in Newnan, a traditional social etiquette and dance training program beginning in fifth grade. She was one of only two African-American students among sixty participants.

©Mary Beth Meehan, Wiley: A former mill worker, Wiley lived in a mill village house in Arnco, before he passed away in 2018.

©Mary Beth Meehan, Tina: Born in Germany and raised as an “army brat” all over the South, Tina now works at a plastics manufacturer in Newnan.

©Mary Beth Meehan, Barbara: Barbara is photographed at the home where she grew up, in Newnan. She believes that the racial attitudes of the past in the South are evolving for the better with each generation

BARBARA — text, originally published in 2017, to be re-published on “ReSeeing” Thursday, May 30, 2019

While working in Georgia, I am trying to consider the long threads of history: how they come together to weave the present moment, tethering the present to the past. If I’m to make work that helps people see past their bubbles into the lives of another, mustn’t I look backward, to see how these bubbles were created?

In Newnan, black and white people have lived side by side – and in almost equal numbers – since its founding, in the early 1800s. At that time, Scotch-Irish and English settlers moved inland from the coast, bringing their families, their animals, and their slaves. Many built cotton plantations and immense fortunes – soon turned to dust by the Civil War. In the following decades, poor white farmers and freed black slaves, both now tied to the land as sharecroppers, would replant the cotton and bring it to harvest. The landowners, with their newly built textile mills, would turn that crop into a dazzling wealth. By 1910, a local newspaper reported that Newnan was the fourth-wealthiest town per capita in the United States.

I’ve noticed that with many white people in Newnan, talk of the power structure that underpinned the town’s beginnings is met with hushed tones, or outright resistance. What does that have to do with today?, I’m sometimes asked. What is the cutoff date, beyond which we don’t have to talk about this anymore? But with members of the black community, talk of those times rises quickly to the surface. Speaking of his ancestors’ contribution to the town’s white ruling class, one black man told me, “I earned that money for them, and I didn’t get anything.”

So in thinking about Newnan’s founders, I wondered where I might meet their descendants today. I was told they attend a Baptist church in the center of town.

On the Sunday that I visited the church, Barbara caught my eye. She was petite and trim, with a bright blond bob and a rosy-pink jacket. She looked the way I’d imagined a Southern woman would look, and I asked to be introduced to her. I told her about my project, and asked if she’d be willing to let me make her portrait. She laughed, and agreed to let me call her later that week. I asked if she would wear the same pink jacket.

Barbara told me that she’d moved a log cabin onto her parents’ property, but when I arrived at the address I found myself in front of a white house. I called Barbara on her cell phone, and she told me that I was at her parents’ house, but that she’d come to get me. While I waited I looked around – at the vast woods, the flower garden, the American-eagle ornaments everywhere. I couldn’t help noticing a small statue, situated on one of the house’s front steps. It portrayed a black child seated with his ankles crossed, holding an American flag. It shocked me.

Barbara arrived, and we sat down on those steps. She told me about herself – that she’d been a flight attendant for Delta, that she competed in triathlons, that she had two grown children. She had just moved back home, to be near her family, after living in Atlanta for two decades. She told me that her parents’ house had been built before the Civil War, and that the land had been in her father’s family since the early 1800s. She said that her mother’s family had been in the cotton-gin business.

When I asked if I could make Barbara’s portrait there, as she sat on those steps, she chafed a little. She put her hand on the statue and said, “Doesn’t this offend you, sort of, a little? I mean it’s kind of cute, but can you imagine some black person walking up and seeing that? If I had a friend of mine who’s black come here,” she went on, “I just don’t think they’d appreciate their race sitting on the steps. They’re portrayed as being a slave, like ‘the good old days.’ I just don’t know about Little Black Sambo out here. It’s not nice.”

For the next hour Barbara and I talked about this portrayal. She told me about Elvo, her family’s African-American maid, whom she had loved growing up, and her grandmother’s beloved chauffeur, who once drove a birthday cake all the way up to Barbara in Atlanta. “They were not viewed as anything different,” said Barbara. I wondered if she meant that they weren’t viewed as unequal.

“But they were, kind of like, in their place, though,” I said.

“That’s what their place was, yeah. That’s how we viewed ‘em, as just kind of helping.”

“The help,” I said.

“Yeah, there you go,” she said. “The Help. Driving Miss Daisy.”

I could tell Barbara didn’t want to criticize her parents, yet she talked of their views as both generational and persistent. I asked her to name a stereotype of black people that she’d often heard. “Lazy,” she said quickly, and added, “When I lived in Atlanta, you know, you just see a black guy walking with his pants half down and you’re scared to death. I am. I don’t know why.”

Then she told me a story about a running group she had belonged to, which worked out with homeless men, most of whom were black. Three times a week she rose at dawn, picked up the men in her car, and took them on long runs. They charted one another’s progress, and competed in races. “It’s amazing how you get to know someone like that,” she said. “I mean, you encourage them to come work out, and they become your best friends. And oh my God, it was just a rude awakening. It will be a lifetime experience I’ll have forever. It was wonderful.”

When we were finished making photographs, Barbara and I agreed that we’d meet again before I left town. I admired her honesty, and in the following days I imagined her as somehow wedged between a generation compelled to portray a black person in humiliating caricature – a childlike object on a step – and a generation to which people of color might appear as equals.

I showed Barbara’s portrait to a few people – including a friend of mine, who is black, who said, “She let you set her up like that?,” and Barbara’s mother, who said, breezily, “Oh I love that you’ve got the little black man in there!” When I showed it to Barbara, she gasped at her appearance, making a joke about needing plastic surgery. But then she said, “I love it.

“I love the picture because I think it speaks about the way our country is so divided right now. It speaks about the controversy between the blacks and the whites… . You have the Southern house – the Antebellum house – and the Little Black Sambo holding the American flag. And then you’ve got the eagle, which is the symbol of our country. And you’ve got the white supremacy.”

“Barbara,” I said, “this picture puts you in the position of the white supremacy.”

“That’s what I’m saying,” she said. “It puts me in the position of the white supremacy. I don’t like that. But that’s how it is.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026