Photographers on Photographers: Bree Lamb and Abbey Hepner

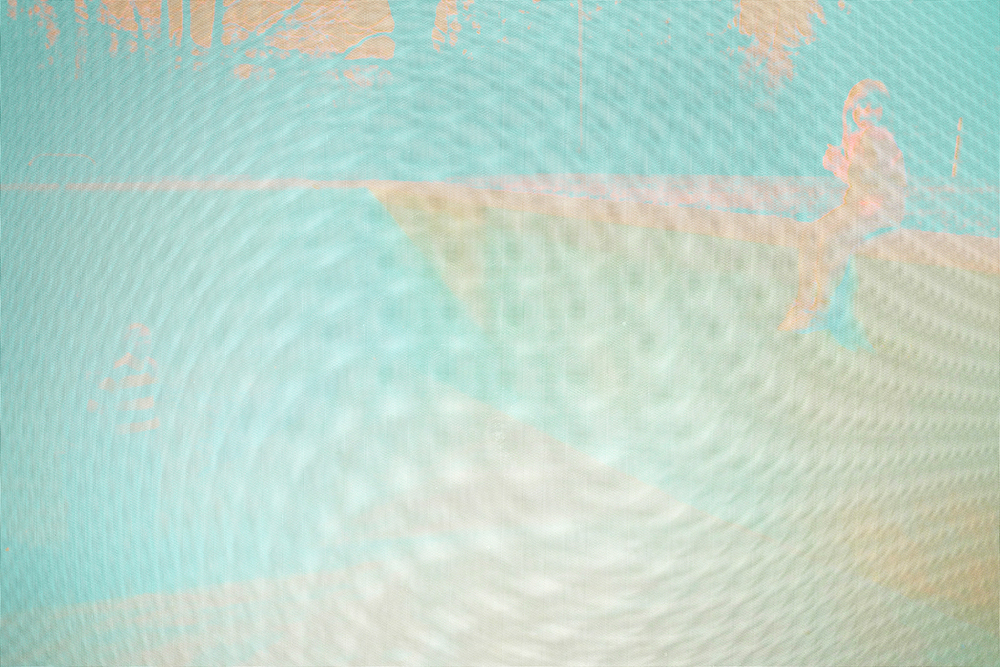

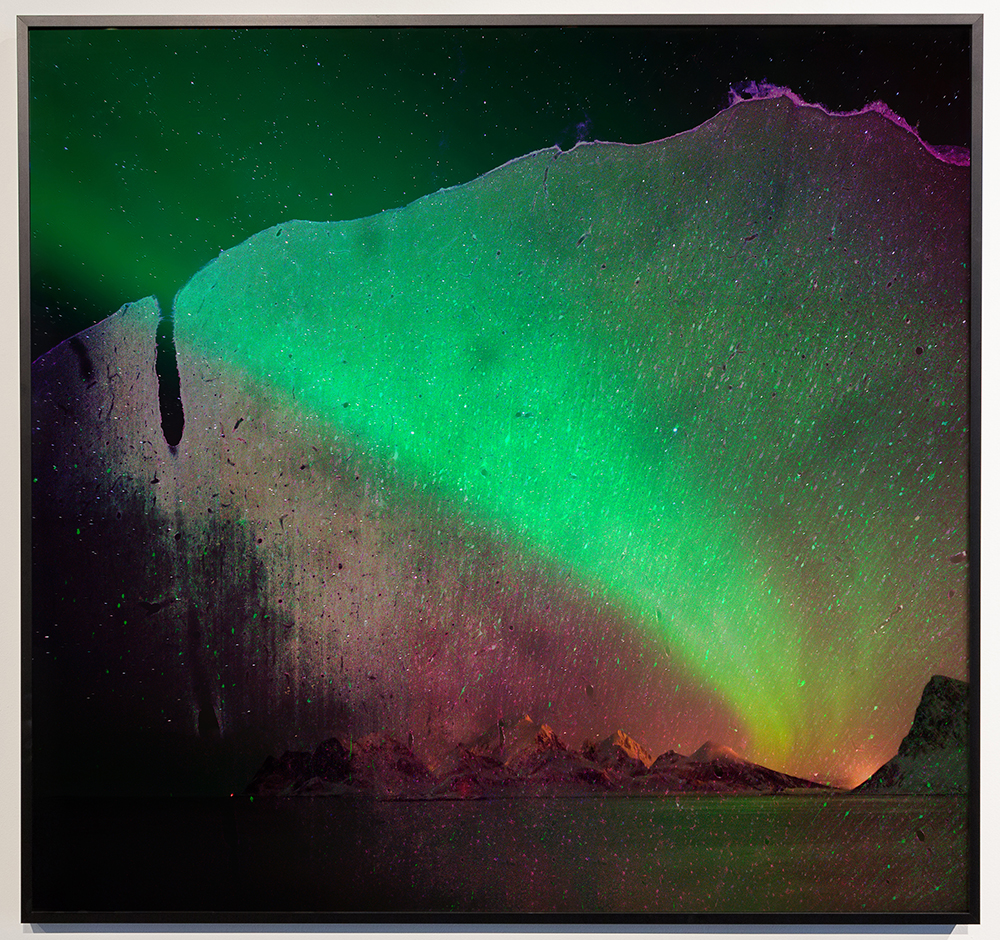

© Abbey Hepner and Mike Avery, Aurora, from the series Optogenetic Cybernetic Translations, Computer Vision Translated Lenticular Print, 2017.

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we are happy to share this interview with Bree Lamb‘s interview with Abbey Hepner. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

I first met Abbey Hepner in 2013 when she was beginning her MFA studies at the University of New Mexico and I was entering my second year. I remember being immediately drawn to Abbey for her sincerity, her insight, and her unique ability to incorporate research-driven data into her creative practice. It can be hard to keep rack of Abbey: she never ceases to create opportunities to conduct her research; she engages with various professional communities; and she devotes seemingly endless energy in her role as an educator. Abbey double-majored in Art and Psychology as an undergraduate at the University of Utah, and over the years I’ve learned what an interesting role this educational foundation plays in her work. I’m very grateful to the lovely folks at Lenscratch for their support of this conversation with an artist whom I greatly admire.

Abbey Hepner received degrees in Studio Art and Psychology from the University of Utah and her MFA in Photography from the University of New Mexico. Her work has been exhibited widely in such venues as the Mt. Rokko International Photography Festival (Kobe, Japan), SITE Santa Fe, the University of Buffalo Art Galleries, Noorderlicht Photofestival (Groningen, Netherlands), and the Newspace Center for Photography (Portland, OR). Her work has been recently highlighted in Hyperallergic, Ars Technica, and Artillery Magazine. She has presented at numerous conferences including the 2015 International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA) in Vancouver, Canada, and the 2016 and 2017 Society for Photographic Education conferences. In the summer of 2018, she was an artist in residence at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in Canada. Hepner is the Chair of the Society for Photographic Education Southwest Chapter and co-founder of Creative Advocacy. She is Assistant Professor and Area Head of Photography at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

Bree Lamb is an artist, educator and editor based in New Mexico. She is Assistant Professor of Photography at New Mexico State University, Managing Editor of Fraction Magazine, and Project Manager at Fraction Editions. Lamb received her MFA in Photography from the University of New Mexico. She is a Beaumont Newhall/Van Deren Coke Fellow and is represented by Gallery 19 in Chicago. Lamb has previously worked for Wildenstein & Company, The Center for Photography at Woodstock, Fovea Exhibitions, and photo technique Magazine.

Artist Statements for Abbey Hepner

[In Process]

One chapter from the forthcoming book “Origins: Family Secrets and the [Dark] History of Women’s Healthcare. The book includes a folded VR viewing device (similar to Google Cardboard) that the user can scan a QR code and view 360-degree videos from anatomical theaters and old insane asylums that were important in the history of women’s healthcare.

The interactive work is also designed for a gallery or museum setting and is best viewed on an Oculus Rift for interaction.

You can see the preview here: Mobile app version here: go.wondavr.com/eonEcWvgTT Web browser here: player.wondavr.com/p/e96c2da4-335a-40e9-a54d-eaa30f206297

Optogenetic Cybernetic Translations

In the series, Optogenetic Cybernetic Translations, I am investigating the artist and scientist as translators of data that illuminate the connections existing in the broader world. My collaborator, scientist Mike Avery, is researching optogenetics, a technique that involves the use of light to manipulate neurons in the brain. I used images from his lab: histological brain sections, stained with immunohistochemical markers, and imaged using confocal microscopy. I then explored how artificial intelligence might interpret these brain scans, creating metaphors for what the future might hold as technology infiltrates our fields.

I used computer vision software, which is a technology concerned with the automatic interpretation, analysis and understanding of information from a single image, to interpret the brain scans. The results of this interpretation included an aurora, fireflies, bioluminescence, rust or texture, light, and military night vision. I paired each brain scan with its corresponding AI translation, resulting in interesting metaphors between cognition and a world full of beautiful, or potentially frightening, phenomenon. By allowing our collaborative work to be interpreted by a third party we are embracing the fact that our work is larger than ourselves and never wholly in our control.

Artist Statemens for Bree Lamb

Volley

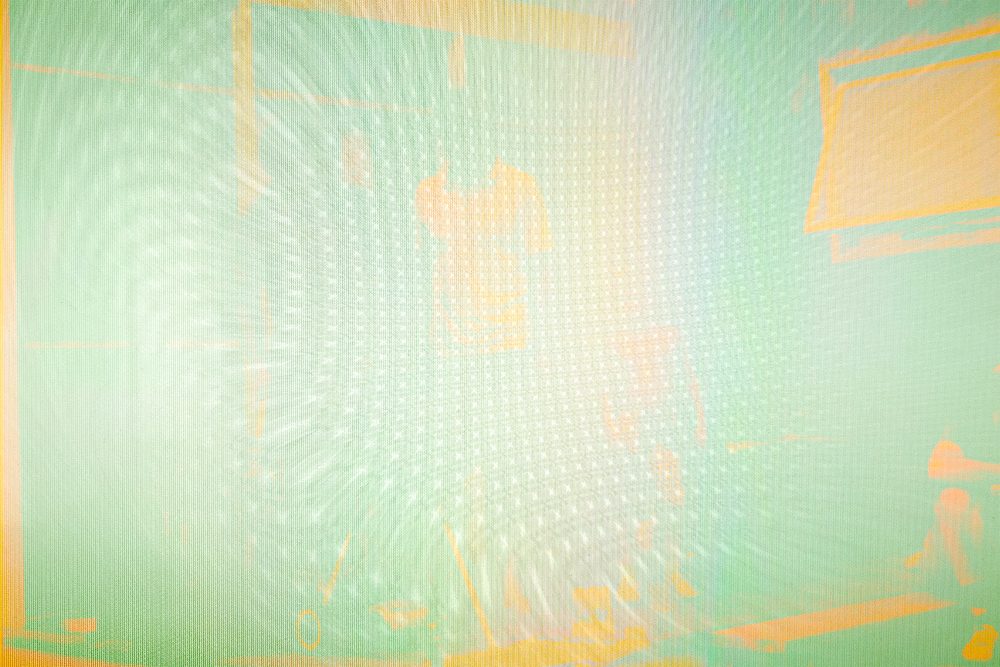

This body of work examines my relationship to my childhood experiences and the images that have come to represent them. I am able to identify events in family snapshots, but I do not recall the actual experiences. In this sense the photographs inform my childhood identity no matter how detached I feel from the experiences themselves, and the distinct color palette of 1980s snapshots plays a large part in how I now perceive my adolescence as an adult.

With these ideas in mind, I transform the original snapshots into a visual language that more accurately depicts my disintegrating relationship to the events in the initial capture. I photograph the original images and digitally sample a variety of prominent colors within each image. I then photograph my computer screen individually filled with each selected color and I blend the subsequent images with the original snapshot. The technique of photographing the screen creates moire patterns, and I emphasize these patterns in the final image as a way to open a dialogue about the cultural shift of snapshot photography from the physical to the digital realm.

The surface of the final images consists of color fields and moire patterns with faded silhouettes and hints of photographic information. The large prints create a dynamic visual experience for the viewer; drawing her or him in with the pleasing pastel color palette while simultaneously repelling through the use of disorienting patterns. The optical interference created by the layers of digital artifacts makes it difficult for the viewer’s eye to discern exact content or rest within the frame; disrupting any familiarity or intimacy commonly associated with the personal snapshot. With these visual tactics, I hope to communicate the inherent disconnect between experience, representation, and memory.

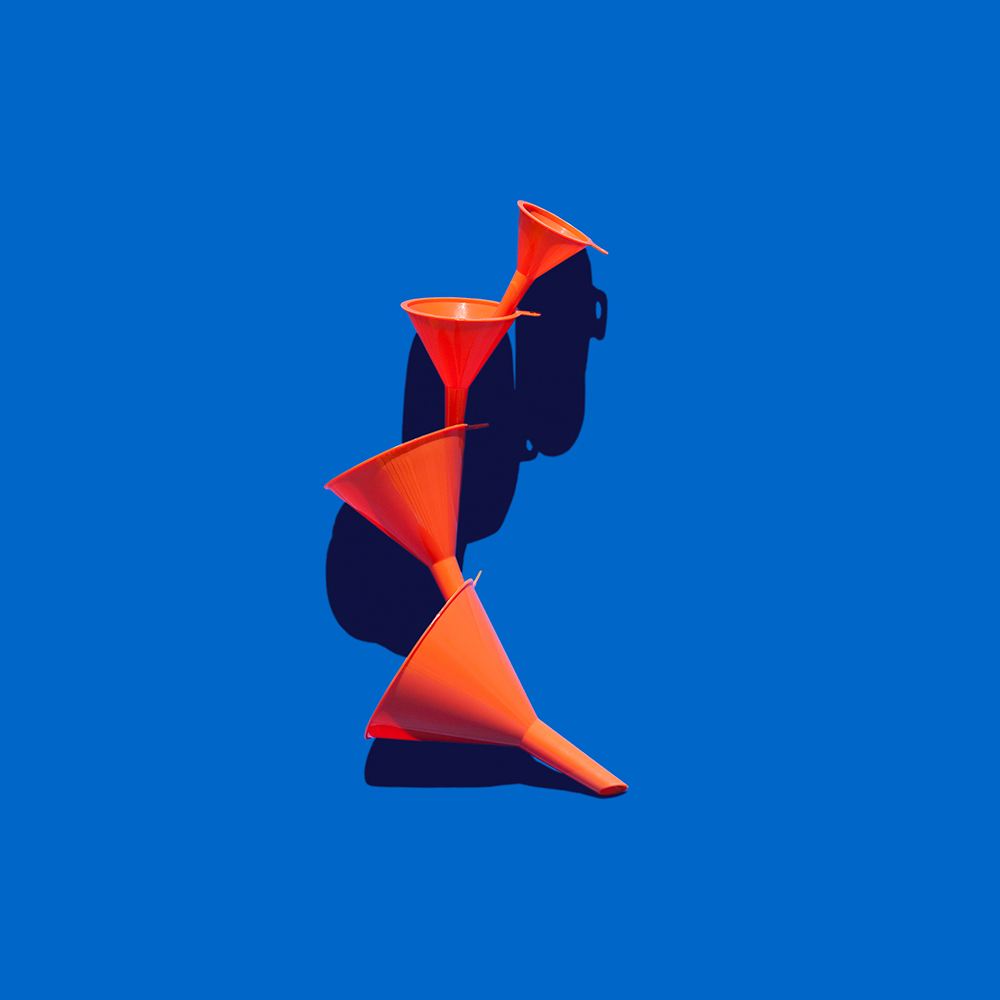

A House, A Home

In the series, A House, A Home, I isolate ubiquitous household objects as a way to investigate traditions of domestic American life. My observations are rooted in my own personal indulgences, expectations, and questions, as well as how I see myself existing within this larger system. I’m interested in revealing some of the complex layers of this shared cultural vernacular through pairing the familiar with the unexpected and creating anticipation that is never quite resolved. The interventions and commercial style of capture re-contextualize the objects as a way to challenge traditional domesticity, to pose questions about social conventions, expectations and stereotypes, and to highlight consumption and convenience as staples of American popular culture.

Bree Lamb: As a starting point, I’d love to know how you find inspiration for work, and to what degree you feel your background outside of the arts (in Psychology) plays a role.

Abbey Hepner: My work is almost always about health and healthcare. I studied art and psychology in my undergraduate education and then worked as a case manager for a community mental health organization after I graduated. My fascination with health and human behavior naturally led me to psychology. In 2009, I was in a debilitating car accident, and it forced me to quit my job and take a few years to recover. I started a commercial photography business in Seattle, Washington, because I could make my own schedule that accommodated my healing, and I slowly started to make art again.

I was always reading about health and technology, so it made sense that my work started to envelop those themes. I’ve made a lot of work on nuclear issues and environmental pollution, and the psychology behind how we deal with or ignore public health issues is a significant interest of mine. Some of the inspiration for my work comes from reading about current health issues and ethical debates surrounding them. Our health is being used as a currency more than ever. Sometimes we offer it up willingly in pursuit of something we believe in, such as technological advancement, but it continues to affect marginalized communities the greatest. I am sure that my own health vulnerabilities have played a role in the motivation behind my work, as has the experience of having family members whose health was affected by living downwind from the U.S. nuclear tests conducted in Nevada during the 1950s. These issues are a part of a larger epigenetic story that I have to tell. I have a sense that most artists are aware of the motivating reasons behind the work they do, but it took me years before I made the connection between my personal and familial experiences and the work I make.

© Abbey Hepner, The Digital Operating Theater at the Galleries of Contemporary Art, Installation of 360-Degree Photographs and Videos on a VR Headset and Pigment Prints on Silk, 2019.

AH: I have always admired your work. I know memory and identity are common themes in your work, and you seem to be very conscious of how your past has shaped who you are and the way you view the world. Can you talk about this?

BL: It’s so interesting to hear how the personal and familial experiences that exist in your work have only begun to make themselves clear to you in recent years. The work that is the most interesting to me, as both a viewer and a practitioner, is that which gives some direction but also has the ability to shapeshift depending on the viewer and her/his/their experience. I believe that the depth that you create in your work, from your social commentary to your personal reflections is part of what makes your work so successful, and allows it to be relatable to a large population.

Like you, my work always contains an underlying personal connection, but I’m rarely aware of the specifics when I’m creating. It generally takes me years to see clearly what my interests are. Memory has become a theme in my work in the last few years, but I’m curious about the failures of memory, or the blinders that memory can create in each of us. Memories are some of the strangely crucial building blocks of each of our identities, yet they are rarely, truly palpable and often in a constant state of change. In this sense, I don’t view memories as a stable entities, but rather as stories that each of us calls upon for different reasons – to share, to connect, to honor, to move on from. In the body of work Volley, I’m less interested in my specific childhood memories, and more in the shared practice of calling upon photographs to describe or dictate a time period. I’m also fascinated with the complications of having an experience, recording that experience, and using a photograph or an object through which to recall the experience.

In my latest work, To Throw a Football Over a Mountain, I’m thinking about the tragedy or complications of nostalgia by revisiting places of personal significance and photographing them in a detached manner, as an outsider or curious observer. When I first began investigating notions of memory, I was often asked if my work was nostalgic, and over time I’ve realized that the work acknowledges, questions or perhaps critiques nostalgia, which to me is quite different than the work itself being nostalgic. In terms of having a clear idea of facets of identity or my memory, like you, I’m able to learn more about myself by working intuitively and at a later time pulling apart some of the underlying interests.

BL: How does, or how much, does a body of work change or grow from the initial idea to its final creative output?

AH: My work changes and evolves as I work through it. The medium that I work in or the technical tools that I use are always tied to the concept. Conceptually, I tend to have a literal approach in the beginning. Sometimes that is necessary, but usually, the work develops stronger metaphors and begins to coalesce after several iterations. Some projects take me a few weeks and others, like Origins, take years and involve multiple “chapters.” I make a lot of failures along the way. When I am deep in my work, it begins to speak to me and tell me what it needs to become. One of my significant challenges as an artist is that I am not always ready to listen or brave enough to create the work that needs to be made. Sometimes it takes years before I understand the real meaning or drive behind the work. I often put work on the backburner and then come back to it, but I try not to abandon it entirely. I tell my students that if they abandon their work, it will haunt them. I really believe this is true. It’s an incredible privilege and responsibility to make art.

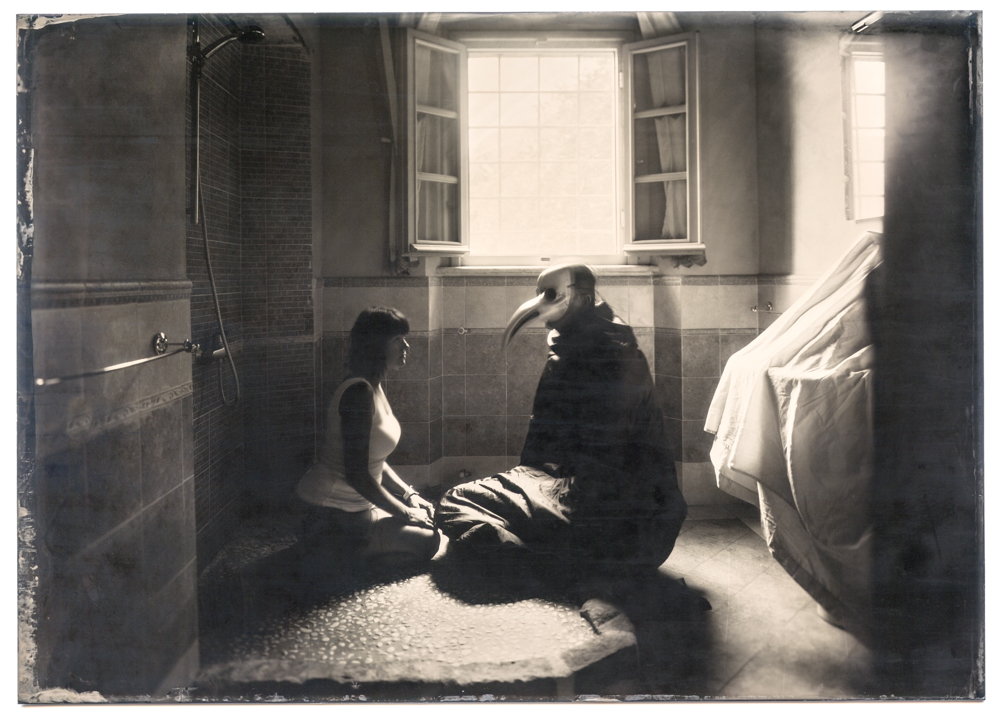

© Abbey Hepner, Plague Doctor, Inside the Villa San Rocco, Benabbio, Italy, 5″x7″ Wet Plate Collodion Tintype, 2018

AH: I think this is an exciting part of our process, to be open to change over time. Can you talk about how your work evolves as you create?

BL: Like most artists, I have a variety of approaches to making work. Sometimes the concept comes first, and I try to visualize how the specific idea can come to life. Just as often, I have a vision for a specific aesthetic language that I want to use, and begin to experiment and make the work before I really know what the project is about. I think that the idea, whenever it presents itself, should direct the means and methods of its final output and it’s important to be flexible as the project develops. I think that your advice to not abandon an idea is excellent. I’d also add to not rush an idea, and to expect failure. I constantly make bad work – work that doesn’t land, or is not conceptually or aesthetically appealing, or all of the above. I’ve had ideas for projects and put them through several iterations only to finally admit that nothing is working. However, oftentimes, that kernel of an idea that failed will reappear years later in a different body of work and find its way into a new, fruitful project. I feel grateful when I’m able to create something that someone else can connect with.

AH: Absolutely, I agree that you can’t rush an idea. I often find that it reappears in later work as well.

I just recently moved from the West to the Midwest, leaving behind my first home. I was surprised at how attached I had become to the house, because of what it represented for me. I thought a lot about the social expectations attached to homeownership like domesticity and child-rearing. The notion of “home” can be complicated for a lot of people. Psychoanalyst Carl Jung believed that in dreams, a house is a symbol for our psyche. I found myself thinking a lot about your work, A House, A Home. It’s such a brilliant project, and I have been pondering some of the questions you are posing in that work. When did the work start and what inspired it?

© Abbey Hepner, Pinel’s Intervention, 5″x7″ Wet Plate Collodion Ambrotype, 2018. (After Tony Robert-Fleury’s 1876 painting depicting Dr Philippe Pinel releasing the madwomen from their chains at the Salpetriere in 1795.)

BL: This project came about organically when I graduated from the University of New Mexico and moved back to Southern New Mexico with my long-time partner. I was having a difficult time finding a balance between my creative practice, my teaching career, and my domestic life. I started paying attention to the questions that I was frequently being asked, such as how the house was coming along, when we might get married or if we were going to have kids. The questions come from a place of genuine care and curiosity, but the polite responses don’t normally reflect the complexities of romantic relationships and domestic engagement. I want to be clear that these questions don’t bother me, because I realize that I frequently ask people the same questions. I began to pay attention to these measures of social and domestic success that we place on one another in American culture. I also began thinking about the way that we speak about life in America and certain colloquialisms that we use, such as “rose-colored glasses,” “the glass is half full,” “when life gives you lemons,” amongst many, and I began to embrace common phrases as inspiration for images as well as image titles.

The project was inspired by personal events, and early in its development it became clear to me that the images needed to exist in a common visual space in order to give access to the viewer, and to allow room for a variety of interpretations regardless of one’s socioeconomic status, cultural or ethnic background, and sexual or gender identity. For this reason, I wanted to utilize common visual tropes of advertising photography, something I believe each of us has access to. I employ a single, angled light source to emphasize highlights and shadows, and I rely on color relationships between object and background. I observe these strategies in popular marketing strategies, and in the work I exploit them as a way to encourage the viewer to recognize the visual space that I’m using, and to then call into question the subject matter of the ubiquitous objects themselves, or perhaps the unexpected arrangement of the objects.

Through the work I’m hoping to pose questions about convenience and consumption as staples of American popular culture. I am not trying to point a finger, or say one way of living is better than another, and I’m absolutely guilty of my own indulgences and I am completely immersed in these systems of consumer culture. I am terrified about global warming and the state of the planet; but I also like to order things from Amazon from the comfort of my home and have them arrive in 2-3 business days. It’s a complicated system, with shared responsibility, and I hope that the work can also touch on the successes and failures of personal growth and self-reflection, as well as interpersonal relationships and gender performance.

BL: Can you talk about the importance of engaging with professionals from various fields? How do these relationships develop and how do you see art engaging with science and technology?

AH: Artists have always been pioneers of technology, and the history of photography intersects with many different branches of science, from the discovery of radiation to the invention of X-Rays. My work, engagement, and collaboration with individuals outside of the field of art is a reflection of my curiosity and interest in subjects like nuclear energy and neuroscience. I’ve been fortunate that curiosity led me to work with some really brilliant people. A few years ago, I met Ginger Shulick Porcella at the Medium Photo Festival in San Diego. At the time she was Executive Director of the San Diego Art Institute, and she got me involved in an exhibition that was hosted there titled, “Extra-Ordinary Collusion.” The project, organized by Chi Essary, paired artists with scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies at UCSD. That’s how I met scientist Mike Avery and began the collaboration that resulted in “Optogenetic Cybernetic Translations.”

Mike was researching optogenetics, a technique that involves the use of light to manipulate neurons in the brain. He was participating in ongoing research, and so some of the photographs that I was taking in his lab couldn’t be used in the exhibition. The limitation provided me with a creative challenge. At the time, there was a lot of media discussion about the role of technology and fear about the jobs it might take away. Mike and I talked about artificial intelligence and what the future might hold as it infiltrates our simultaneous fields. I decided to use the images that I had access to in his lab: scans of primate histological brain sections that were stained with immunohistochemical markers. I put them through a computer vision software program to see how artificial intelligence would interpret them. The AI thought that the brain scans were an aurora, fireflies, rust, and military night vision. I paired each brain scan with various stock images that corresponded to the AI translation, resulting in interesting metaphors between cognition and a world full of beautiful, or potentially frightening, phenomenon. By allowing our collaborative work to be interpreted by a third party (the AI), I was taking a less cynical approach and, we were embracing the fact that our work is larger than ourselves and never wholly in our control.

Engagement with other professionals also includes being involved in the art community. I’ve always had supportive peers and colleagues. The friends I made in graduate school at the University of New Mexico (UNM) are still some of the coolest people I know! When I left graduate school, it was important that I stayed connected to a community that was serving artists and promoting their work. I Co-Founded Creative Advocacy with sculptor Leslie Martin, who I met at UNM. Creative Advocacy focuses on art as a conduit for social change and our programming advocates for sustainable creative practices that challenge the current social structure. Each year we curate an exhibition in a different city and include the work of artists from around the globe. In 2018, our exhibition “Addressing Power,” which we curated with Aziza Murray and Katelyn Bladel, was at the CFA Downtown Studio in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Earlier this year, we hosted “Collective Voices” at Modella Gallery in Stillwater, Oklahoma. We are also working on an artist residency in Oklahoma. http://www.creativeadvocacy.org

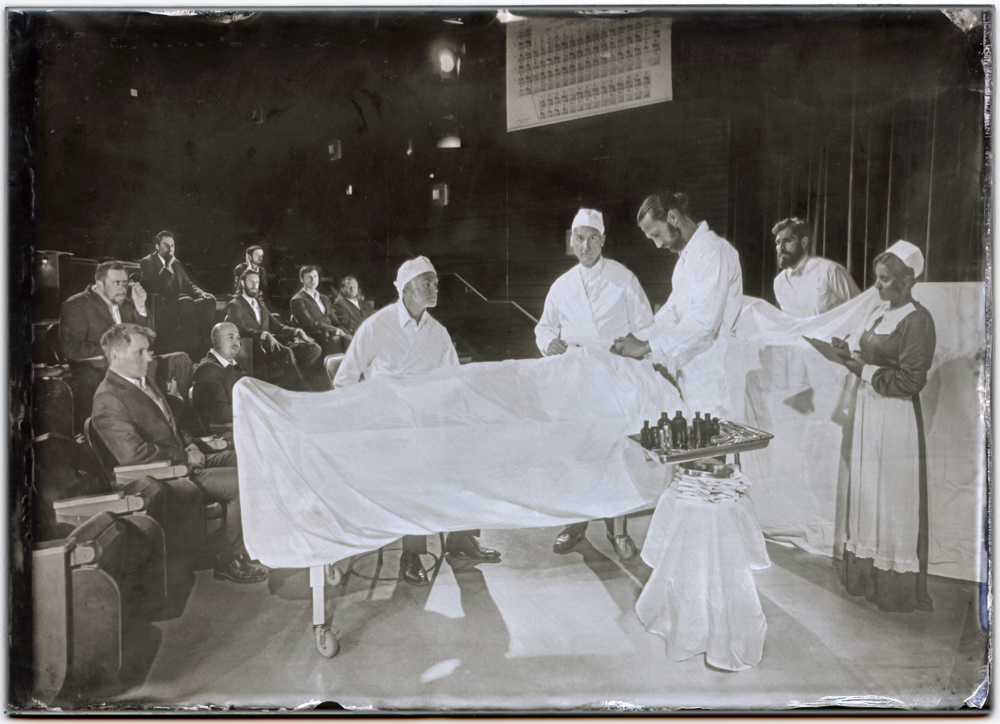

© Abbey Hepner, The Invention of Hysteria, 5″x7″ Wet Plate Collodion Ambrotype, 2018. (After “Une Leçon Clinique à la Salpêtrière” by Pierre Aristide Andre Brouillet, 1887.)

AH: You have been very involved in the arts community as well. It has been so great to see the work you are doing as Managing Editor for Fraction Magazine. Can you talk about this involvement?

BL: I love the vision of Creative Advocacy and the outreach that you and Leslie are involved in. I also know that you contribute to the Strange Fire Collective, the platform that was founded by Jess Dugan, Hamidah Glasgow, Zora Murff and Rafael Soldi, and focuses on highlighting work made by women, people of color, and queer and trans artists. It’s great to connect with other artists and professionals, and I couldn’t agree more about the importance of community. I feel so fortunate to have had incredible mentors and peers throughout my formal educational settings as well as the various internships and jobs I’ve had along the way.

As far as my work with Fraction, I met David Bram, the co-founder of Fraction, while I was at UNM. I started out helping him with the website and over the years my role naturally developed into more of a leadership position. It’s been such an incredible opportunity to be able to review submissions on a consistent basis and to connect with really interesting, creative individuals. Fraction, like Lenscratch, and other great platforms such as Float Magazine, Aint Bad, Photo Emphasis etc, help to provide opportunities for artists at different stages of their careers, and consequently build an accessible online database for research and inspiration.

Through my role at Fraction, I’ve been fortunate to participate in portfolio reviews and festivals, where I have the opportunity to meet photographers in person and learn more about their diverse interests and to witness their passion firsthand. It’s great because as much as we all try, some things get lost in communication via artist statements or social media identities, and I really value the opportunities I have to meet artists face to face. It helps to keep me motivated to deepen my research, to connect with my communities, and to make work that, if I’m lucky, might have some value to someone else.

BL: I admire your ability to integrate various mediums and technologies into your work. It always seems fluid and responsive to the core concepts but you really dig deep in your practice and push yourself in terms of process and output, from uranotypes, wet-plate collodion, to lenticular prints, to VR. Could you share a bit of insight into your approach to media?

AH: Thanks so much, Bree. It’s important that the medium that I use is connected to the concept, and that is why my work ranges in execution from alternative to digital photography and coding to interactive art. My work almost always lives in and through a corporeally-sensitive approach to the photographic medium, though. It’s about health and the body. I’m trying to activate something physical in the viewer by asking them to move and interact, such as with the lenticular prints or virtual reality (VR). Similarly, in Transuranic, a series of photographic prints made with uranium, I am creating tension and discomfort in the installation by including Geiger Counters on a print that emits a warning sound based on the amount of radiation present. There is no real threat to the viewers in the exhibition, and the amount of uranium in the prints is meager, but the fact that we know it’s present is what makes it unsettling.

I am interested in perception and material, but that means that my work doesn’t always translate well on a screen and is intended to be experienced in person. I haven’t come up with a solution to help people understand the work digitally, other than to provide a video of the interactive nature of the work. I am also fascinated with history, and I use historical photographic processes to communicate through that material.

I am currently working on a book: “Origins: Family Secrets and the [Dark] History of Women’s Healthcare.” It dives into 4,000 years of medical history and the physical-psychological debate that has plagued women’s medicine. I investigate how pelvic pain disorders have been understood through time, and I look at the history of endometriosis. Endometriosis is a painful and often stigmatized disease that drove my grandmother to take her own life at the age of 24. One chapter of the book investigates early scientific practices for representing the body that occurred in anatomical theaters, operating theaters, and insane asylums. These sites were located in Europe and during the 1600-1900s, public dissections and operations were performed there. I created 360-degree photographs and videos in these spaces and included them in a VR app. The photographs are included in the book along with a device, similar to Google Cardboard, that slips out of the back of the book so that the viewer can “interact” with the spaces through the app. I wanted the viewer’s body to be indicated within these spaces, and I wanted them to feel immersed in them. Putting on a headset, that closes off other senses and absorbs the viewer in the sites and sounds of the theater provided the closest thing to being there. It is a very different visceral experience from looking at a still photograph. Many people find VR to be discombobulating, myself included. As a result of the car accident I was in, I have a different way of processing things neurologically, and VR is challenging. It has been an interesting process to create something with a technology that sometimes makes me sick! I have learned a lot about methods of creating VR content that counters vestibular issues, and I am trying to make art with an awareness of how accessible it is to individuals with varied abilities.

Another chapter in the book looks at the shift that occurred in the 1800s, where doctors transitioned from the belief that pelvic pain was a disorder that they could locate within the body to believing it was psychological or even the ‘nature’ of being a woman. I am interested in reenactment photography and what performing historic scenes might suggest about the “truth” of them. I staged photographic scenes that mimicked famous medical paintings and illustrations from the 1800’s. I chose to create ambrotypes (wet plate collodion process on glass) because it was used by early practitioners such as Charcot, who photographed his female patients, attempting to prove their pathology. The chemical process also has ties to medicine. It uses ether, which was an early anesthetizer. At the time that some of the operating theaters were in use, they did not have modern anesthetics. The Old Operating Theatre in London, which operated on women, would have had hundreds of men in the stands watching a doctor operate on a conscious patient. The stories from the time-period are horrible. In 1840, ether started being used in operations and provided considerable relief to the medical community. The wet plate process also uses collodion, which is a sticky substance that is used to seal up wounds after an operation. Collodion is still used in surgeries, including those commonly used for endometriosis. These materials provide a visceral connection, and I reference memory, history, and performance. Because the images are on glass, they appear as a negative image until they are backed with black, and then they read as positive. I like the way the work changes and suddenly gets “revealed” in this way, as well as the fact that glass references medical materials like pathology slides. Right now, the photographs are mainly illustrative, so we’ll see how the work changes over time.

AH: Perception and material seem very important in your work as well, and you have an incredible sensitivity to color. Your thesis work, “Volley,” blew me away. That is work that also needs to be experienced in person and not on screen. It seems like perception plays a role in the work “A House, A Home” as well. You mentioned that you get a lot of technical questions about the work. Can you talk about your approach?

BL: Thank you so much, Abbey, I really appreciate your support! I definitely have an affinity to certain color palettes – I just can’t seem to get away from them! My goal is to respond to color that I see existing in certain spaces and incorporate it thoughtfully, but I think it’s totally possible that I just have tunnel vision and am unable to escape pastels. My technical approach changes from project to project, but I recognize that I can be very rigid at times and it’s important for me to push myself with new mediums and installation methods to break out of my often strict, two-dimensional approach.

Volley was a very different project for me, because it was the first work that I made that challenged perception of a 2D image and asked for an active viewer. The prints are 40” x 60”, with a matte laminate and framed without glass. The final compositions are derived from digital copy-stand images from my family’s photo albums. I never planned to use these photos for a project, but when I was doing my color-correcting/spotting/post-processing regime in Photoshop, I had a bizarre experience. As soon as I “corrected” the color, my connection to the content of the image was totally lost. It became clear that the funky color palette from the 1980s drug store processing was ingrained in my understanding of my childhood through these images.

For each composition, I digitally sampled 7-10 prominent colors within the original photograph, filled my computer screen with one sampled color at a time and then photographed my computer screen. In doing so I created colorfields with moire patterns, where the pixels on my camera’s sensor did not align with the pixels on my monitor. I overlaid these images on top of the original, playing with blending, opacity, and dodging and burning to arrive at the final images. My hope is that through the combination of the underlying photographic content, the color fields and the digital artifacts, the viewer’s curiosity is piqued, and the pleasing pastel colors draw her/him/them into the work. However, the content of the image can really only be traditionally understood from a distance of 5-10 feet, and it falls apart the closer you get to it. We are so used to bringing something closer to us to discern the content, and the opposite is necessary with this work. I hope that the incorporation of the screen also speaks to the transition of our physical photo albums to a digital realm, and asks the viewer to consider their own interactions with snapshot photography.

One of the things that I love about photography is that the ways in which we are able to make images continues to expand. I think any sort of combination of methods to find your end result it great and appropriate, so long as it serves the work. With A House, A Home, I’m frequently asked about the amount of Photoshop and post-processing that is used in this process. For these images, I purchase used pillow cases or sheets as the base color and pair them with particular objects to establish an attractive color scheme. In the final photograph, the objects, light source, highlights, shadows and color are all created in camera. Call me old-fashioned, but I prefer to clone out the wrinkles in the sheet in post as opposed to using an iron. This technique tends to flatten to final image in a way and creates an odd visual space where the objects are simultaneously grounded by the shadows but also appear to be floating. I like the complexity of this visual space, and prefer it to some of my first images from this series where I used a different approach.

BL: How do you see your creative practice feeding into your interests as an educator?

AH: Teaching keeps me from getting too cynical, and it challenges me to be continually learning. I love my role as a lead learner, and my students teach me a lot as well. I integrate current events and my student’s interests in the content that I teach. That is similar to the way I create, using what’s happening in the world socially and politically as an impetus for the content that drives my work. In this way, the work is current and relevant, but it’s also exciting and provides conversation starters in class and extends learning opportunities outside of it. My interest in collaborations also extends to teaching. Last year I co-taught a course at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs with Geographer Mike Larkin and a couple years ago, my Advanced Photography class did a really fun collaboration with students in Meggan Gould’s photography class at UNM.

I demonstrate my methods of investigation to my students, but I also give them access to learn about how other artists and creative thinkers work. Creativity is like a muscle, and it gets stronger and more efficient when we are generating ideas, experimenting, looking at work, and doing things that inspire us. I try to create a space for students to flex their creative muscles in a way that makes sense to them. We live in a world that can be stifling to creativity, and so this practice is vital. I am not saying it is easy, though. I take workshops and give myself assignments frequently to challenge and motivate myself. I regularly tap into my art community when I am needing support or inspiration. I had great mentors throughout my education that still keep in touch, and many of my peers are teaching so I have an awesome community to reach out to. I also love the community that the Society for Photographic Education has provided for me.

AH: What about you, how does your creative practice and your role as an educator overlap?

BL: That’s so great. I totally agree that the creative practice needs consistent tending to through diverse methods of investigation. It’s so interesting to hear you say that teaching keeps you from being too cynical. I can definitely identify with that notion. My work might by colorful, but it certainly contains some underlying cynicism and working with students helps to keep that part of me in check. They are brimming with energy (most days!) and they absolutely keep me on my toes.

There is definitely a symbiotic relationship between my creative practice, my work with Fraction and teaching. For me, it boils down to recognizing the importance of my communities and coming to the table with an open mind and a genuine desire to connect and to exchange ideas. We all have so much to learn from one another, and I am really grateful for the opportunities through Fraction and teaching to meet people with a wide variety of life experiences. My personal motivation and creative practice are naturally enhanced by these engagements. I love discovering new artists and various approaches to subject matter, and I work hard to deepen my student’s curiosity. It’s important to recognize that an idea can be visualized in a multitude of ways, and that it takes time and care to bring it to fruition.

By teaching in a university system, I have the opportunity to work with students for several years and see their interests and communicative skills develop. It’s very exciting, but it’s also challenging because you have to manage a lot of different personalities and find new ways to maximize your value as a facilitator of creative growth. It’s important for me to establish a sense of community, to convey my sincere interest in each of my student’s ideas, and to make clear that we are all invested in each other’s progress. The classroom needs to be a safe space for experimentation, and the system functions best when everyone shows up ready to get to work!

AH: Thank you so much Bree! This has been such a delight!

BL: Thank you so much, Abbey! And thank you to Brennan Booker, Aline Smithson and everyone at Lenscratch for the opportunity.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026