Photographers on Photographers: John-David Richardson & Danna Singer

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we are happy to share this interview with John-David Richardson‘s interview with Danna Singer. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

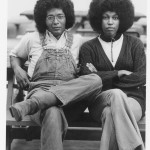

I came across Danna Singer’s project, If it Rained an Ocean, while in graduate school, and I remember feeling like I could see myself and my family through her images. Her photographs are unapologetically authentic, addressing the stain of classism on America. Danna humanizes a group of people that are often discarded and stigmatized, and she does so with an incredible amount of strength and empathy. It was an absolute privilege to speak with her about her family, influences, and her process of making photographs.

Danna Singer is an American photographer who received her BFA from Pratt Institute and her MFA from Yale University School of Art. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally and has been published by the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker, and the ACLU. She currently lives and works in Philadelphia, PA and New Jersey.

John-David Richardson is a photographer and educator based in Cincinnati, Ohio. He received his MFA from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and his BFA from Northern Kentucky University. He was named the Grand Prize Winner of PDN’s 2018 Student Photo Contest, Second Place Winner in the 2018 Lenscratch Student Prize, and a 2018 SPE Student Award Winner for Innovations in Imaging. His work has been shown nationally, internationally, and featured online including NPR, The Wall Street Journal, VICE, Feature Shoot, and PDNedu, among others.

If It Rained an Ocean

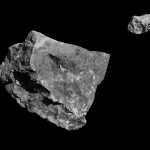

There is a population in America that is forgotten about. In many ways, they aren’t free. They struggle to be seen, to make ends meet, to feel worthy of the comforts that many Americans easily afford. These are the subjects of my pictures, my immediate family members, friends and neighbors from the working-class neighborhood in New Jersey where I grew up. This work and series of pictures is a look at my relationship to my family and community. Some images are documents, moments that unfolded before the camera. Others are created from memory or staged portraits that strive for a different truth, one that is in conversation with the history of painting and photography. But all, deal with the struggles of the working-class, the cycle of addiction, lack of education and bigotry that defines the America in which I was raised.

Someday I’ll Find the Sun

I am a product of poverty. The atmosphere of my upbringing prepared me for a world where economic and social worth is defined by class. My parents separated when my sister and I were young, and my mom raised us along with her numerous abusive male partners in a trailer on the outskirts of town. These men would come and go, each one exhibiting more violent and destructive behavior than the one before.

Our family fought to make ends meet, but their efforts constantly fell short due to drug and alcohol addiction, domestic violence, and a lack of education. I watched my mom struggle with trying to find and hold a job without having a formal education beyond grade school, bouncing disability check to disability check all to realize that she would have to choose between paying the overdue electricity bill and keeping food on the table. Being surrounded by such a traumatic environment at an early age dramatically shaped my worldview, and I came to understand family as a collision of love and hate.

Someday I’ll Find the Sun functions as a poetic reflection of my personal experiences growing up in the cycle of poverty. I seek to understand my family’s troubled history by building relationships with people that mirror members of my family, finding people that are simultaneously callous and tender. Using photography, I hope to generate a conversation about the class divide that consumes our country, and the people affected by a system constructed to serve those in power.

JDR: Hi Danna, I wanted to start by thanking you again for sharing your work and speaking with me. Could you share what brought you to photographing your family for If It Rained an Ocean?

DS: Thank you for asking me. I am an admirer of your work so it’s an honor. If It Rained an Ocean began in 2015 while I was in grad school. When I first started making the pictures I didn’t anticipate that it would be a body of work. I thought I’d just make a few pictures of my family, have something to show at crit and hopefully become a better photographer while trying to survive my grad program. Shortly after I began though, it became clear that I was touching on something that felt important and so I continued.

JDR: That’s incredibly thoughtful of you to say. Thank you. Could you talk more about that feeling?

DS: The work took a deep dive into some hard terrain pretty quickly. The first picture I made for the series was an image called “After,” which is of my niece in the camper that is parked outside my parents house. It was a staged image that addressed inappropriate and sometimes criminal relationships between young girls and older men in my neighborhood. I wanted to make an image that described the psychological aftermath and emotional space that exists and often remains. I then made images that looked at addiction, teen pregnancy, abuse and neglect, all of which was very present in my life and the lives of people I knew. It felt like an honest description, important and necessary.

JDR: Has your relationship with your family changed after working on If It Rained an Ocean?

DS: It mostly strengthened my relationship with them. They showed up for me in such a generous way by allowing me to come with my camera for years and make difficult images that are often not flattering. They did that because I was family and that is such a selfless act of love.

JDR: Where do you find inspiration?

DS: I look at a lot of photographic work for inspiration, particularly Deanna Lawson, Diane Arbus, and Larry Sultan but I think it’s helpful to look at a variety of artistic disciplines as well. There are similar concerns in most art making and understanding how another artist handles subject matter and material can be valuable.

When I began working on my series If It Rained an Ocean, I thought a lot about Junot Diaz’s Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and how he used both formal and vernacular language. It was equal parts street and sophistication and I wanted to work those disparate ideas into my visual language. It took the shape of my combining a snapshot aesthetic with staged and documentary modes of picture making. This created a cadence in the edit that felt unexpected.

Diego Velázquez’s painting Las Meninas is something I return to a lot. His composition and use of space within the frame is just incredible. Every inch is activated with light, gesture, and reflection. I find it exciting and something I try to use in my own compositions.

Lynne Ramsay is another artist I look at. Her film Ratcatcher is particularly beautiful and nuanced. I appreciate how she lets a moment linger and trusts the audience to stay with her. She manages to find the tenderness in exhaustion and hope in the most desperate exchanges.

Also, Wim Wenders’ film Paris, Texas is always an inspiration. His use of color and reflection is masterful and takes my breath away.

JDR: I’m drawn to how you approach this project from multiple angles, moving between constructed and intuitive imagery. Could you elaborate on your process, and how you shaped the work visually?

DS: At my core I am a formalist but I like to employ different modes of picture-making to create a rhythm in the work. There is a rawness and ugliness in the snapshot aesthetic that feels right for certain pictures. I use on-camera flash to create images that act as evidence, an indexing of sorts. It’s confrontational and loose and in direct contrast to the staged images in the work which helps shape the tension. The formal images appear to provide a retreat into more tender moments with an attention to gesture, and delicate lighting but it’s a false floor because the subject matter is equally challenging. I also like to combine the two modes by creating staged snapshots. These images are particularly satisfying for me because they disrupt and complicate the reading of the work as they draw into question photography’s relationship with truth-telling, and implicate me as the photographer.

JDR: Throughout the history of photography, images of poverty have been partially responsible for creating and perpetuating stereotypes. It’s something I often struggle with in my work, and I’m curious if you have any thoughts?

DS: It’s a real concern for those of us working with this subject matter but I don’t think images of poverty are inherently problematic. The fact that there are so many people struggling and that there is still a need for them is the bigger issue. Many photographers and visual artists work have been criticized for perpetuating stereotypes and I don’t always agree. It’s often an easy argument that targets the messenger instead of attacking the issues in the message. I think about Kara Walker’s work and its relationship to photography, the silhouette and how she pushes boundaries and makes the audience confront a shameful history. It’s a critique of representation and a reaction to trauma and that creates a platform for conversation.

Finding solid ground with one’s position within the work is key and telling a story fully takes time. Realities can be one thing and also another and showing both is vital. It’s important to be critical of the images we make and to be clear with our intention and then we need to stand behind the work and fight for it.

JDR: I love your response, Danna. Author Eudora Welty has a quote that I’ve always loved,“ One place understood helps us understand all places better,” and I think about it when I see your work. What are you hoping to communicate with your photographs?

DS: That’s a beautiful quote and one that I whole-heartedly agree with! I hope that my work communicates the weight and depth of the psychological damage that exists when one is trapped in cycles that lack opportunity and possibility. The oppressiveness is not only evidenced in the absence of resources for the working-poor, but in the emotional fallout. I want my pictures to show the destructiveness of classism, the claustrophobia of these places and the grace that can be expressed in spite of it all.

JDR: What’s currently exciting you in your work?

DS: I had taken a long break with the work and so re-engaging and adding images to the series has been exciting and rewarding. The recent images have been focused on the messaging that our young girls receive, the roles that are assigned and how that plays out in the expectations they have for their future. This thread is helping to shape a more complete narrative by looking at the next generation, and telling the story of lives lived over time.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Richard Lloyd Lewis: Abiogenesis, My Home, Our HomeApril 23rd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Jason Lindsey in Conversation with Areca RoeApril 21st, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: J Wren Supak in Conversation with Ryan ParkerApril 20th, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Josh Hobson in Conversation with Kes EfstathiouApril 19th, 2024