Photographers On Photographers: Dylan Hausthor and Lotte Reimann

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we are happy to share this interview with Dylan Hausthor’s interview with Lotte Reimann. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

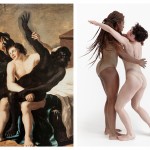

Photographer, curator, printer, and editor, Lotte Reimann’s work blends appropriated images with authored ones, creating compelling worlds—ones where facts are malleable and reality becomes fantasy. My personal work revolves around floating realities and the complexities of mythmaking, and am consistently inspired by Reimann’s ability to combine lyricism with research to tell her stories. Reimann is captivated with the history of art’s function in the contemporary, and her 2016 project Temptation examines the very specific world of drapery studies. In this project, Reimann combines appropriated images found on the internet, with the work of Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault, a psychiatrist from the early 1900s who became obsessed with drapery and studied women with a fetish for silk.

Reimann’s project goes much deeper than research. There is an emotional dissonance to Temptation—it brings up questions about the male/female gaze, power struggles in portraiture, and the complexities of fetish as content.

Dylan Hausthor’s work is an act of hybridity—an effort to render field recordings into myth. Interested in the human threshold between growth and an abyss of lunacy, the stories he looks for are found at the end of dirt roads and in the tops of fir trees.

He received his BFA with Honors from Maine College of Art and his work has been showcased nationally and internationally. He founded Wilt Press in the spring of 2015 and currently works as a cinematographer, bookmaker, photographer, and chief editor of Wilt Magazine from an island in Maine.

His work has been described as having “too many pictures of deer”.

Dylan Hausthor: Will you give us a brief explanation of your latest project Temptation?

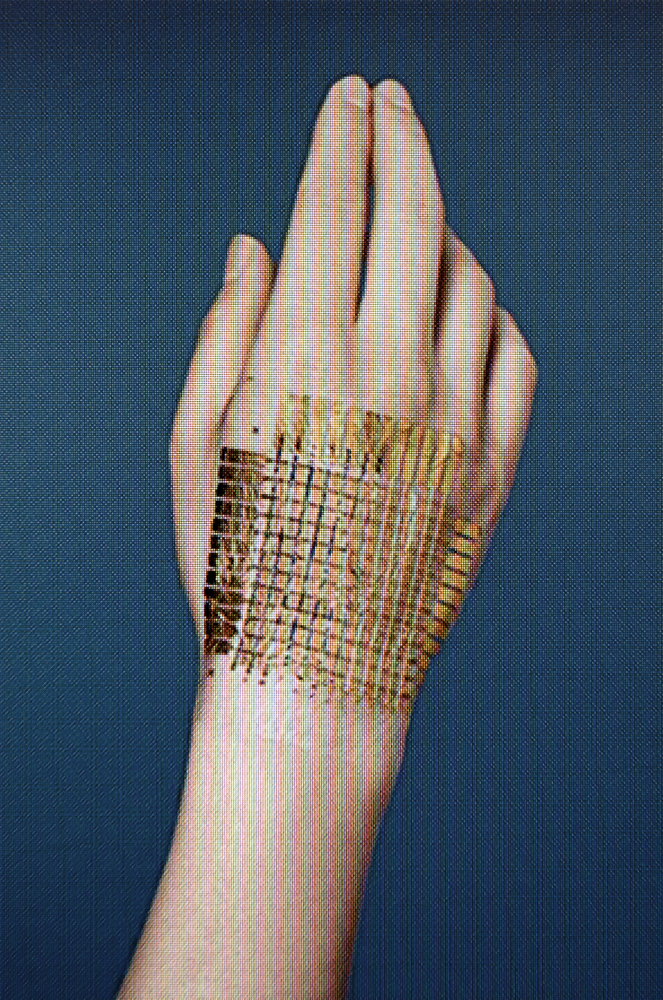

Lotte Reimann: Temptation is my first research-based body of works. I was interested in the process of discovering coherences and dependencies in historical and contemporary image production and reception. Starting with an online discovery of self-portraits by men dressed up in female clothes, I developed a broader and more absurd question—What could a photographic drapery study be?

Due to my own fascination with socio-cultural constructions, I began to get interested in photography and voyeurism, female/male gaze, and men’s and women’s opposing traditional positions in the arts. “She” as “his” object of desire and scientific research and personal interest.

In Temptation, I intertwine my contemporary collection of pictures from the internet with the historical work of Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault. His work materializes in photographs he shot of Moroccan women in their traditional robes around 1918, and case studies he wrote on women with a sexual passion for silk fabric dating from around 1908. I show the work along with a semi-fictional report, which intertwines Clérambault’s obsession with cloth into my own research.

DH: Your role as an author in Temptation feels removed in a very specific way. Most of your projects have a combination of found, made, and manipulated imagery—Was this process intuitive or more structured?

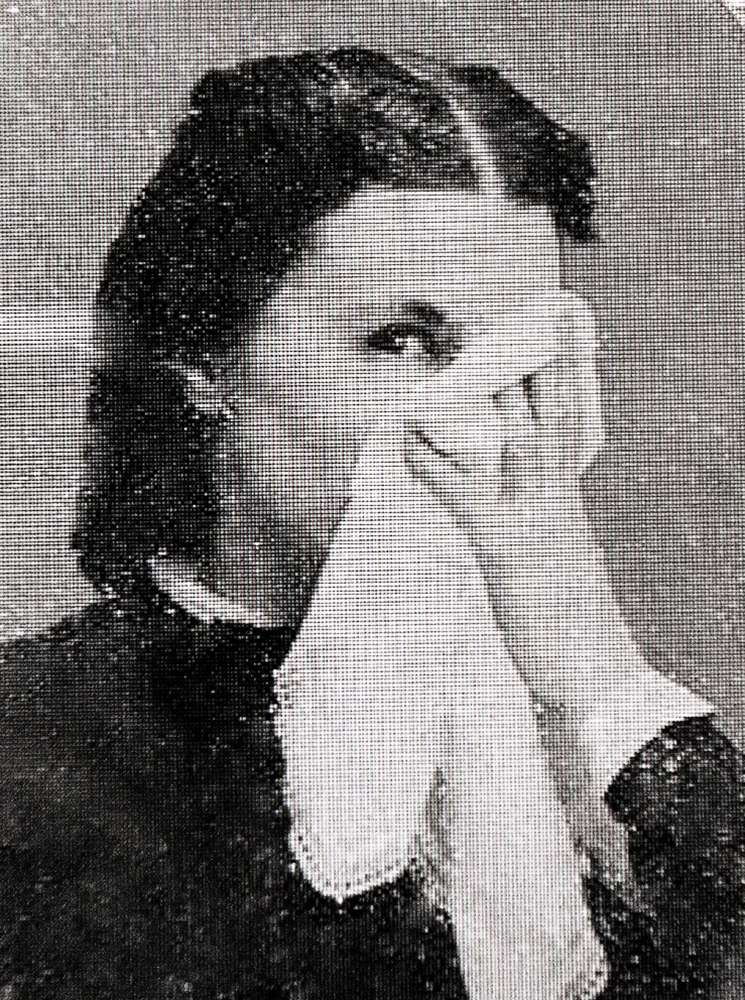

LR: I started integrating found images into my work in 2011. When I was realizing my first visual autofiction Guffaw. I had in mind this picture of my mother posing on the hood of my red Volkswagon, but I didn’t have the time to travel to Germany—where she lived—so I commissioned my stepfather to take the picture for me.

In the sequel Colts and Fillies I included pictures sourced online, which I initially downloaded as inspiration. I realized it wouldn’t make any difference to the story I was telling to remake these photographs—on the contrary it would stress the conceptual fact that the story. It was a half-fiction.

In Temptation I only foremost act like an objective researcher—one who is personally withdrawn or non-existent in the product—if that actually exists.

DH: There are some amazing formal similarities between Temptation and your project Bis Morgen im Nassen (a 2013 project about so-called ‘wetlookers’, a community of people who swim with their clothes on). Literally, they both seem to be formal visual examinations how cloth looks on a body, but with very different theoretical questions. Can you talk about the relationship between the two projects?

LR: Of course, Temptation or Dr. de Clérambault wouldn’t exist without its predecessor Bis morgen im Nassen. I think my curiosity in photographed draperies sparked after realizing that I had actually made three projects addressing clothing, including the reflectoporn images [DH: This was one of Reimann’s projects about a niche fetish that existed on eBay of people selling items that reflected the photographer naked. Reimann herself got her account suspended for posting one]. This continuous recurrence revealed the importance of garment as a visible form of culture in my work and made me want to find out more about it—et voilà, Temptation was born.

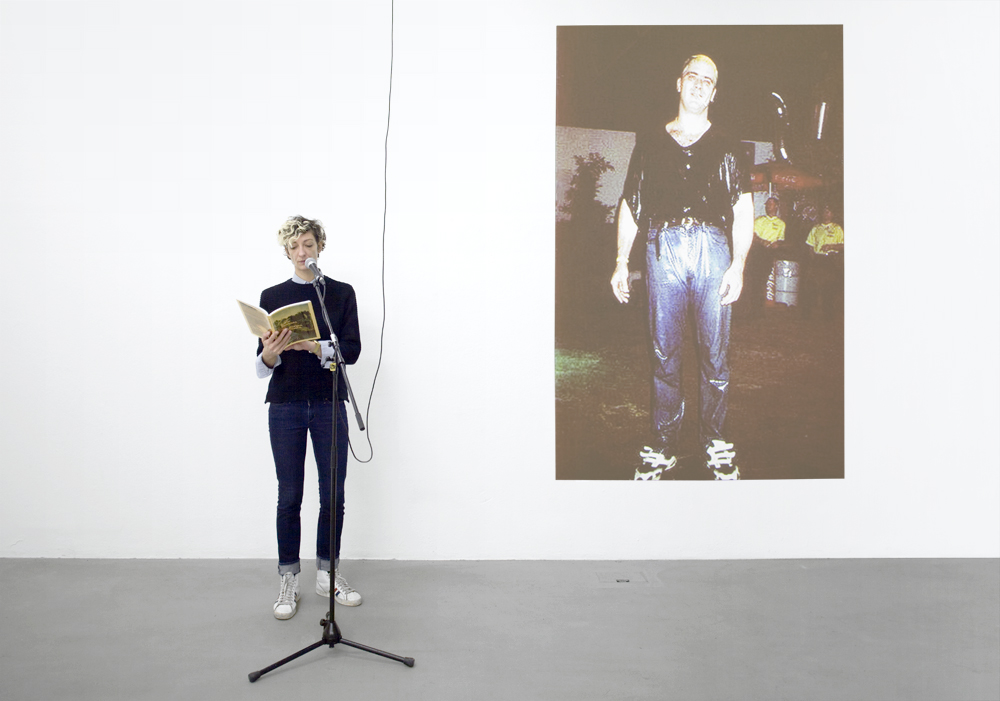

DH: I wonder about your relationship to sculpture. The function of your individual image seems to be about objects in space—your installations and book designs don’t shy away from three dimensions. How do three dimensions play into this work?

LR: I love sculpture. Sculpture is real, it’s objects in front of you. It’s material—physical contact and relation. It’s not like the image, which is even linguistically related to the imaginary.

When I was an art student, I wondered at some moment why photographs were exhibited in space at all. I was especially thinking of documentary exhibitions, which would show a series of pictures—initially made to be printed in a magazine—now framed and equally sized, put up in a row at eye level. Why make me stand upright and walk down facing a wall distracted by a painful back if I could also be comfortably sitting on a couch studying these same photographs at any hour of my choice. Based on this impression, I decided that in my own practice, photographs either belong in books. Or, if exhibited in space, they better acknowledge this circumstance.

DH: I’m really interested in how activism functions in your process—it feels apparent in all of your work, sometimes more obvious than others. Do you consider yourself an activist?

LR: Hmm… Actually no, I don’t consider myself an activist. Of course, I have ideas about freedom, equality, and the likes. But being an activist to me sounds a bit like trying to propagate preconceptions. I think I’m more interested in uncovering structures of our media-permeated cultural world by trespassing, by not sitting in line.

Starting off with auto-fictional accounts, challenging photography’s still presumed document character, I came to explore and extend other people’s biographical stories. In these projects, the question of authorship simultaneously became important and irrelevant. Recently, my work evolved into research-based continuations and appropriations of other researcher’s lives and works. In this process-oriented work, I can uncover strange misperceptions of objectivity in historiography and archival research.

So coming back to your question, I am very much interested in understanding cultural constructions—especially in relation to media—and if I happen to undermine clichés on the fly, I am happy to do so. I’m certainly trying not to act on preconceptions, both as a person and within my work.

DH: How has your recent work as a curator and teacher fed into your process?

LR: Oh, that’s hard to say. The first show that I’ve curated just opened, and I have since then not really gone back to the studio. It certainly made me realize a general approach in my artistic practice: A tendency to turn private things public.

The curatorial concept of this specific exhibition derived from a moment in a studio visit with Torsten Scheid, director of the Kunstverein Hildesheim. We were standing in front of my bookshelf and I kept pulling books off the shelf and he complimented every single one. After much deliberation, we decided that allowing the public a glimpse into my private book collection was a great concept on its own.

DH: Thanks so much for talking Lotte. It’s such a privilege every time we get to chat and it renews my excitement for images. I hope the Netherlands is treating you well and your residency goes fabulously.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Sonja Langford: The Way of Being a WomanMay 16th, 2024

-

Photography & Anthropology: Gloria Oyarzabal, “USUS FRUCTUS ABUSUS”May 3rd, 2024

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024