Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New Mestiza

This weekend artist and editor Vicente Isaías shares the work of artists exploring critical issues on borders, sovereignty, and self-determination.

Every year since 2014, Mexican artist, activist, and educator Emilio Rojas has been reopening an inkless tattoo scar that mirrors the U.S.-Mexico border on his back in his ongoing annual performance, Heridas Abiertas (to Gloria). In it, Rojas’ body becomes a reflection of the territory’s violent history but also a canvas for healing and resistance. The ritual is as visceral as it is poetic and symbolic.

Drawing upon the influential work of Texas-born chicana artist, writer, and leading figure in gender theory, Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New Mestiza, Rojas’ long term durational artwork is a powerful critique of border politics. The seminal book is not just a source of inspiration and theory for the artist but rather a deeply emotive and personal subject matter through which Rojas has been able to understand his layered and, at times, conflicting identities. As Rojas remarks, “Anzaldúa has given me the words to understand my experience as a queer latinx immigrant with Indigenous heritage battling identity, discrimination and cultural hybridity while surviving existing within multiple worlds and intersections.”

In this interview, Rojas and I discuss his enduring relationship with Anzaldúa’s revolutionary ideas, her lasting legacy, and the profound influence she had in his artistic practice and pedagogy.

Emilio Rojas is a multidisciplinary artist working primarily with the body in performance, using video, photography, installation, public interventions, and sculpture. He holds an M.F.A. in Performance from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a B.F.A. in Film from Emily Carr University in Vancouver, Canada. As a queer, Latinx immigrant with Indigenous heritage, it is essential to his practice to engage in the postcolonial ethical imperative to uncover, investigate, and make visible and audible undervalued or disparaged sites of knowledge, narratives, and individuals. He utilizes his body in a political and critical way, as an instrument to unearth removed traumas, embodied forms of decolonization, migration, and poetics of space. His research-based practice is heavily influenced by queer and feminist archives, border politics, botanical colonialism, and defaced monuments.

His work has been exhibited in exhibitions and festivals in the U.S., Mexico, Canada, Japan, Austria, England, Greece, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Holland, Colombia, and Australia, as well as institutions such as The Art Institute and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Ex-Teresa Arte Actual Museum and Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, The Vancouver Art Gallery, The Surrey Art Gallery, The DePaul Art Museum, SECCA, the Syracuse University Museum of Art, The Johnson Museum of Art and The Botin Foundation. From 2019-2022 Rojas was a Visiting Artist in Residency in the Theater and Performance Department at Bard College in New York. He has taught in the M.F.A. programs at Parsons the New School and the low-res M.F.A. programs at PNCA in Portland, Oregon, and University of the Arts, in Philadelphia. He is currently a visiting full-time professor at Cornell University in the School of Art, Architecture and Planning. His a traveling survey exhibition Tracing A Wound Through My Body accompanied with a bilingual catalogue, is currently exhibited in its third iteration at the Usdan Gallery at Bennington College in Vermont, to continue at SECCA, North Carolina, and Artspace, New Heaven.

Follow Emilio Rojas on Instagram: @performanceroarte

Website: emiliorojas.studio

VC: In your ongoing durational artwork, Heridas Abiertas (to Gloria), you use the tattoo scar on your back as a canvas to mirror the U.S.-Mexican border in your blood. How does this annual ritual of reopening the wound and reshaping the line contribute to your reformulation as a person?

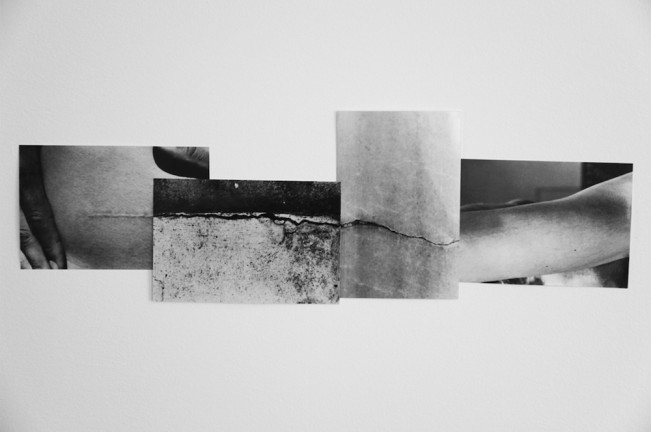

EM: In the piece Heridas Abiertas (to Gloria), ongoing since 2014, a tattoo artist re-opens every year the line of the US-Mexican border without ink on my back. The mark made from my 1rst vertebra to my last creates a 22-inch bleeding wound during the performance; then it becomes a scar until it is reopened again, rendering into the body the site where “the third world grates against the first and bleeds” (Anzaldúa, 25). The skin becomes territory, the bleeding geography translated into a line and edged in blood.

After carving the border every year, I clearly feel the geography in the pain, running down the length of my back. I also feel the wound heal every year as the open wound becomes a scar. In this way, my body shows me, year after year, that healing is possible. Like the piece Shibboleth of artist Doris Salcedo, permanently inscribed in the floor of the TATE Modern, there is always a mark where trauma happened, a scar that is left as a reminder.

I constantly ask myself, could we truly heal the wounds the border has inflicted in the lives of so many of us? I became obsessed with the formation of borders around the globe, the sociopolitical and historical implications of these lines forced into the land by wars, colonialism, imperialism, and the competition for resources. The way in which borders have been used as sites where hatred and xenophobia are directed and mobilized towards immigrants and refugees.

I began looking at the lines of borders, how when abstracted from the map, they look like cracks or scars. I started drawing with pencil the actual geographical borders of Latin America on pieces of paper and continued drawing following the lines until it became a sort of topography. These drawings are called Topographies of the Margins. They became a sort of meditation, drawing hundreds upon hundreds of lines, thinking about the liminal spaces in between and what each line represented and separated. Who drew the borders as we know them today?

VC: When was the last time you reopened this wound on a public performance?

ER: I just performed Heridas Abiertas (to Gloria) for the ninth time at The Immigrant Artist Biennial in New York City at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts [on December 9th.] This piece has completely transformed me as a person, an activist, and as an artist. My commitment is to do this performance every year until the US-Mexico border is no longer a site of trauma, a territory scared by the loss of so many lives. I’ve been able to process and heal some of the trauma I’ve experienced as an immigrant with this piece, but also grow from the conversations and collaborations with so many migrant tattoo artists and audiences. The pain is now familiar; it has become an annual ritual which helps me understand the border in a different light, to mourn and honor the lives lost, and to begin to heal this collective wound.

VC: How often do you return to Anzaldúa’s words for inspiration?

EM: I often think of Anzaldúa as my spiritual and artistic madrina, or even mother, although I never met her in person, her archive, work and legacy have been an undying source of inspiration and nourishment. I came into the work of Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa when one of my best friends, artist Guadalupe Martinez, gave me a copy of Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, as a birthday gift more than 15 years ago. As she handed me the wrapped book with a red ribbon, she said softly: “This book will change your life” and it did. Through her work, Anzaldúa (1942-2004) has given me the words to understand my experience as a queer latinx immigrant with Indigenous heritage battling identity, discrimination and cultural hybridity while surviving existing within multiple worlds and intersections.

So much of my work, especially the pieces that relate to borders are all dedicated to Anzaldúa, who has inspired me to translate her archive, poetry and theory into embodied gestures through performance and collaborations with immigrant communities. Her work called me to respond through my body, through the land, and through the collective creation of a new border pedagogy, that centers the queer woman-of-color feminism — the Chicana feminism that Anzaldúa articulates. In this way every work from this series includes a parenthesis (a Gloria ) inserted in the title as a way of homage and delineation of the lineage it follows and echoes . I often joke that Borderlands/La frontera is my bible, and as a recovering catholic this statement holds a lot of weight. Anzaldúa has and continues to be a guiding light in my personal and creative journey. I often dream of her and we have full conversations, she has been a mentor from Nepantla, not only as writer and poet but also as an educator and a visionary. I’ve bought this book so many times I’ve lost count, I often gift it to other latinxs, chicanos, first generation, immigrant and mixed race students that take my classes or talk to me after my performances.

I have this practice where I ask Gloria a question and open Borderlands on a random page, and she always responds with advice through her words which continue living. I’ve also met many of her writing comadres and one of her best friends and collaborators, writer Cherrie Moraga. I truly believe she continues to live through us, through every reader, through every friend and student.

The first time I visited Anzaldúa’s archive at the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas in Austin, I held her passport for a very long time, and brought it close to my heart and began weeping uncontrollably. The archivist approached me with a box of tissues, and asked me if I was related to her. Without being able to utter a word I just nodded. As a queer person and as someone living far away from home, I believe that we are given the opportunity to choose our family, our mentors and the networks of support of care that allow us not only to survive but to thrive.

“As Latin Americans, we have a tradition of migration, a tradition of long journeys on foot. Currently, we are witnessing the migration of Mexican peoples, the odyssey of returning to the historical-mythological Aztlán. This time, the movement is from south to north.” — Gloria Anzaldúa

VI: Thinking of this quote from Borderlands, and Thinking about the last quite and given the significance of immigration as a major political issue in the U.S., especially in the context of the 2024 election, is there something in your mind that you’ve been closely paying attention to? What are your expectations or predictions for the impact of immigration on the election year dynamics?

EM: This open wound and the migration to the north described by Anzaldúa and its relation to trauma of this liminal geography has been at the core of what inspired me to teach and perform. Anzaldúa died in 2004 from complications of diabetes, but her work now more than ever is relevant to understand the tensions which continue to increase in this “open wound where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds”. This vague and undetermined place that bleeds through the lives of others, is the emotional residue that clearly demarcates what is defined as the United States of America. Who is allowed in ? Who is welcomed to stay?

This year, 2024, marks the tenth anniversary of the piece Open Wounds (a Gloria), but it also an election year in the United States. It is also the year that I become eligible to become a US Citizen, which I’m not certain yet if I will apply for it or not. What I am certain is that the border will be weaponized by the right and Republicans in these upcoming months, and will be used as fuel to continue feeding the rampant fire of xenophobia in this country. Immigration will play a huge role in the dynamics and debates of this year’s election.

Something in currently in my mind which Ive been paying attention to very closely is the conflict in the Middle East. We are also still living the aftermath of Biden and his administration fully supporting the genocide of Palestinians by the State of Israel, in their relentless war against Hamas after their attack on October 7th. Biden’s unreserved support for Israel’s war may cost him reelection, the war has exceeded 28,000 dead Palestinians including 11,500 children. I believe violence cannot create anything but more violence. The political climate in the US could not be more unstable, and this is felt by so many of us living in this country. I worry about the consequences this war will have in the electoral results, and also about the censorship felt in academia and in the art world. It is truly an overwhelming feeling, which constantly makes me ask this question: What is our role as artist and educators in such uncertain times?

VI: Considering your participative performance pieces, like the one at Emerson Contemporary where participants draw the U.S.-Mexico border in exchange of a Mexican popsicle, you highlight the ignorance and fear surrounding the ‘other.’ You’ve observed that this exercise reveals a collective uncertainty about the border’s actual shape, despite its heavily politicized and guarded nature. How does this realization challenge or inform your philosophical understanding of the constructs of borders and the human tendency to fiercely protect what is, in essence, as Anzaldúa puts it, “vague and undetermined”?

EM: The work you are referring to is called A vague and undetermined place (to Gloria) and was a commission for the Live Art Biennale at Bard College in 2019. It began as an exercise which was part of the border pedagogy workshops with students and community members for Naturalized Borders (a Gloria). The workshops were meant to engage and bring back to life Anzaldúa’s archive and legacy. In this particular exercise I asked them to draw the border from memory on a blank piece of paper, without seeing a map, or any geographical reference. The instruction was to: “Draw from memory the line that represents the border from one edge of the paper to another, try to be as accurate as possible and think about the territories you are cutting through as you draw the line if the left edge of the paper was the Pacific Ocean and the Right edge of the paper was the Atlantic” (If you have some time, please grab a piece of paper and follow this instruction yourself). I realized that each line drawn was completely different from the other, since no one really knows what the line of the border looks like.

Anzaldúa writes in Borderlands/La Frontera: “A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary… it is in a constant state of transition” How is it that the site which defines so much of the identity of the United States, its nationalism and who belongs inside the territory can be so abstract and blurry when it comes to knowing its shape or what it traverses? How do we not know the ways in which the border changes the migration patterns of flora and fauna or the way it cuts through Indigenous territories? This exercise reminded me of the time when in the height of the Iraq war, a reporter went around major cities in the US with a world globe, (with borders but no names of countries) and then asked people if they were able to point to the where Iraq was located in the globe, almost no one could.

A vague and undetermined place (to Gloria) is a mobile paleta cart-turned-drawing studio upon which participants are invited to draw the line of the Southern border in exchange for a paleta (Mexican popsicle) that I make with produce that comes across the border from Mexico (mangos, avocados, tamarind, pineapples, prickly pears, guavas) in collaboration with local migrant paleta makers. While participants from all ages draw the line of the border, I read to them parts of the archive of Gloria Anzaldúa. I continued this piece in community events and public spaces after the Biennial was over, exchanging paletas for drawings of the line of the border, which in the end is only a vehicle to facilitate conversations around the subject of immigration, borders, xenophobia and. displacement. The drawings are recorded through video with a camera that is set on a copy stand. Then the videos are reversed so in the exhibition of this work, when its not being activated by the performance, you see hundreds of hands from all ages and races, undrawing the border, which for me stands as an act of resistance in a time where borders are so heavily militarized, politicized and used as an instrument for division and hate.

“Meritocracy is also a syrup / all “Americans” drip over their / piles of pancakes, / while Amazon workers / try to unionize, / I will take your job, / your titles, / and perhaps / your bullets, / and my sap will flow.”

EM: This is an excerpt of the piece Hands to Hold, a collaboration with Black lesbian poet Pamela Sneed, commissioned by The Center for Human Rights and the Arts, at Bard College as part of The Open Society University Network. The work is centered around 2 durational performances that I devised, in the first one I drank 1.5 gallons of sap from a 250-year-old sugar maple in the Hudson Valley for six and half hours, in the second one I wash my hands with a cast of my hands made out of soap for 8 hours, until the soap disappears. 1.5 gallons is the amount of blood flowing through our bodies at all times. In a way I metaphorically transfused the blood of the tree into my bloodstream. It is an attempt to memorialize the intersections of our relationships to this land and the systems of oppression that we’ve inherited, the legacies of colonial histories, capitalism, white supremacy and empire. It was a reflection of the time we were living as two queer black and brown bodies in the first two years of the pandemic. This part of the poem was written at the same time that the sap of the tree was hitting my tongue drop by drop, the text just flowed during the performance. Everything I was thinking at the time came into the writing: the fallacy of the “American” dream, the myth of meritocracy, the lives lost to gun violence, the abuses that essential workers all over the country were experiencing, and of how much “Americans” love pancakes and the crucial role that maple syrup plays in the fulfillment of this desire. In this work we tried to recognize the labor of artists and black and brown people during the pandemic. It was an attempt to send a blessing to all those hands that by holding on, by working, by nursing, by harvesting, held us through. Hands to hold started a commission but quickly became a journey of gratitude and acknowledgement, a litany to the pandemics (aids and covid-19) and the waves of mourning and grief the whole world was experiencing.

VC: According to you, what is the biggest wound of our collective body as humanity as a whole? Of our mind?

EM: Ay, Vicente, you left the hardest question for the end, and there is no simple answer for it. I feel the collective body of humanity has so many wounds, it is pointless to measure them. We are a patient probably on life support in an Intensive Care Unit in this pale blue dot we call home, hanging to our existence by a thread.

I also do not believe you can separate the body from the mind. “Mind-body dualism” is the biggest fallacy that was left to us by Descartes. The problem is that so many of these wounds have never healed; they remain open and festering, like colonialism, exploitation, invasion, and war. They are deep and profitable, so we continue hemorrhaging. Then there are wounds that constantly cut deeper through our collective skin like borders, resource extraction, mining, global warming, and world hunger. Then there are internal wounds caused by disease, violence, greed, fear, poverty, and indifference. All of these wounds affect the body and the mind and are leading us to a path of self-destruction. To be completely honest, I’m not sure we will survive as a species. I am hopeful that we also have all the tools we need to heal, but we need to do this collectively, and we are running out of time. We are cutting short the lives and existence of so many species in our attempt to keep ourselves alive.

To close, and to not end on such a pessimistic tone, there is a quote by Anzaldúa I found in her archive, written on a piece of paper on a typewriter. It was the earliest mention of Borderlands/La Frontera, which she was calling at the time “Del Otro Lado, a poem in progress,” in the early ’80s. It ends by saying:

“At the risk of sounding simplistic, I believe that the issue of sexuality, of world hunger, and world war stem from the same problem and has the same solution: to stop plugging up the holes on our walls, to stop protecting our borders and territories, to stop making others ‘different’ from ourselves, and therefore ‘alien,’ and therefore ‘enemy.'”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024