Photographers on Photographers: K.K. DePaul and Vicki Richardson Reed

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we are happy to share this interview with K.K. DePaul‘s interview with Vicki Richardson Reed. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

I met Vicki Richardson Reed back in 2014 at an artists weekend at C4FAP in Fort Collins Colorado. Originally, our orbits intersected through Alt Pro and Shootapalooza, but more recently we have connected through our conversations about losing our parents and how the mourning process has impacted our artwork.

Vicki Richardson Reed is a former newspaper photographer and magazine art editor who currently teaches workshops in alternative processes at Studio 224 in Port Washington, WI. She uses plastic cameras as well as vintage, pinhole and digital cameras to explore the natural environment and her personal life and she continues to experiment with alternative processes. Having recently cared for parents suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s, much of her current work centers around memory and family.

Vicki has exhibited throughout the United States, Europe and Asia and won numerous awards. She has been widely published, including Tim Rudman’s, “The World of Lith Printing” (UK), and portfolios in Fuzion Magazine (UK) and Fine Art Photo (Germany), Porcupine Literary Arts Magazine (Wisconsin) and Superstition Review (Arizona State University). Her work is included in the permanent collections of the Racine Art Museum and Port Washington State Bank as well as numerous private collections throughout the world.

K.K. DePaul is an explorer of secrets, combining and recombining bits and pieces of memory to make sense of her family stories.

K.K. DePaul is an explorer of secrets, combining and recombining bits and pieces of memory to make sense of her family stories.

Kim’s award-winning work as a collage artist and photographer has received national and international attention, Her work has been published in Black&White Magazine (UK), EyeMazing, Diffusion, PhotoWorld (China), and All About Photo, as well as exhibitions in the US, Paris, UK, Barcelona, and Edinburgh. She was the recipient of the 10th annual Julia Margaret Cameron Award in 2017, and a member of the TRIBE exhibition at the Fox Talbot Museum.

KKD: I grew up in a very strong matriarchy of women who sewed. I realize now that my grandmother, my mother, and all her sisters embraced needle-arts as their ‘creative outlet’.

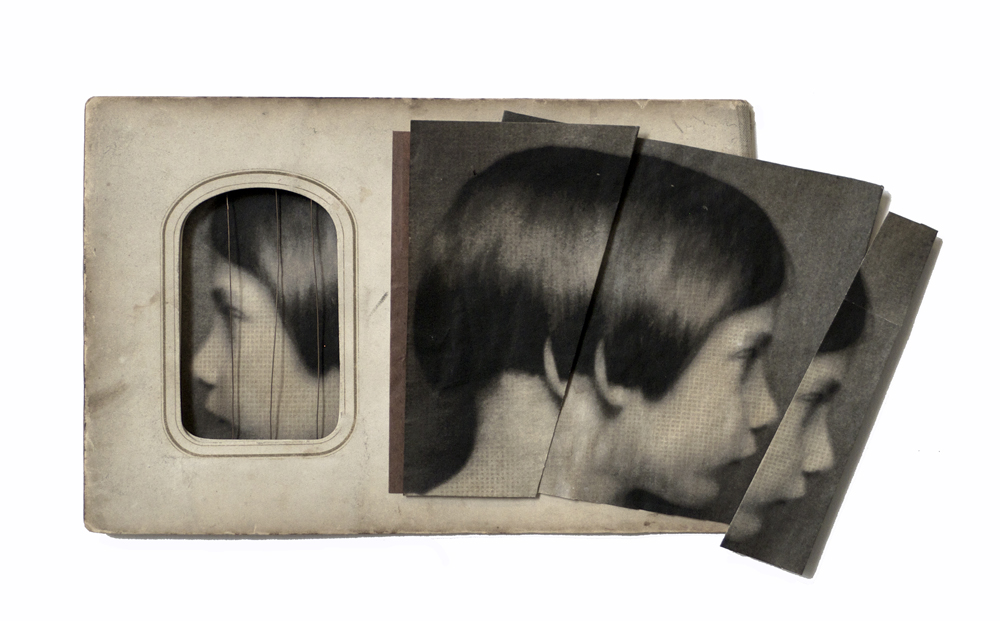

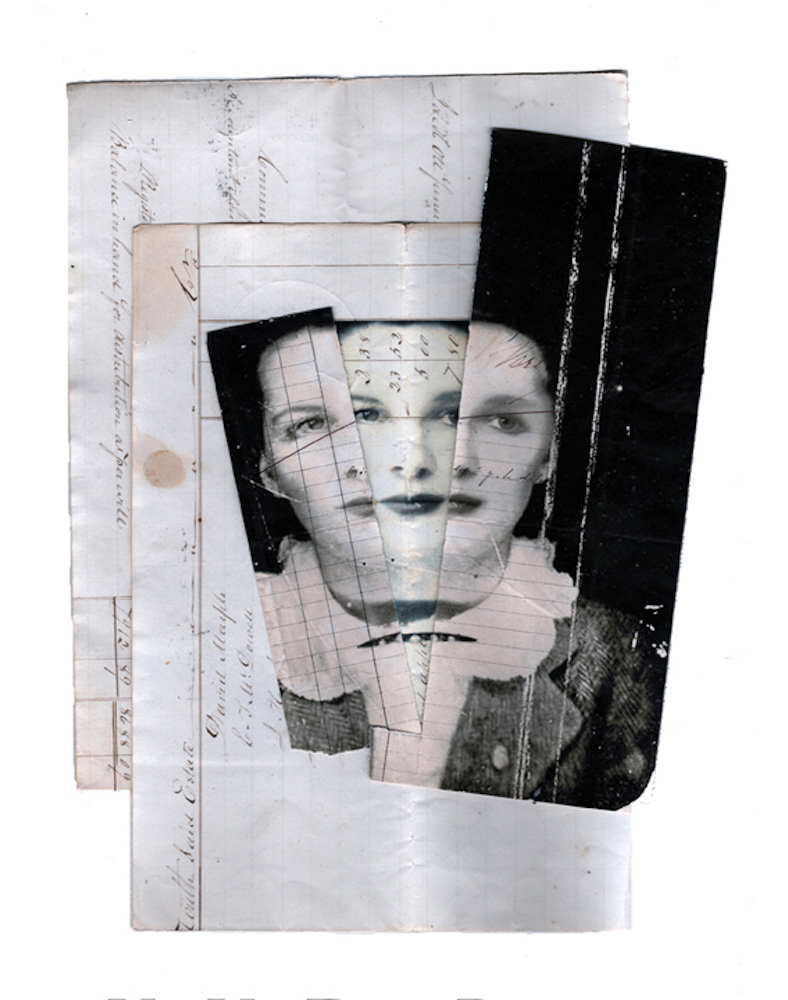

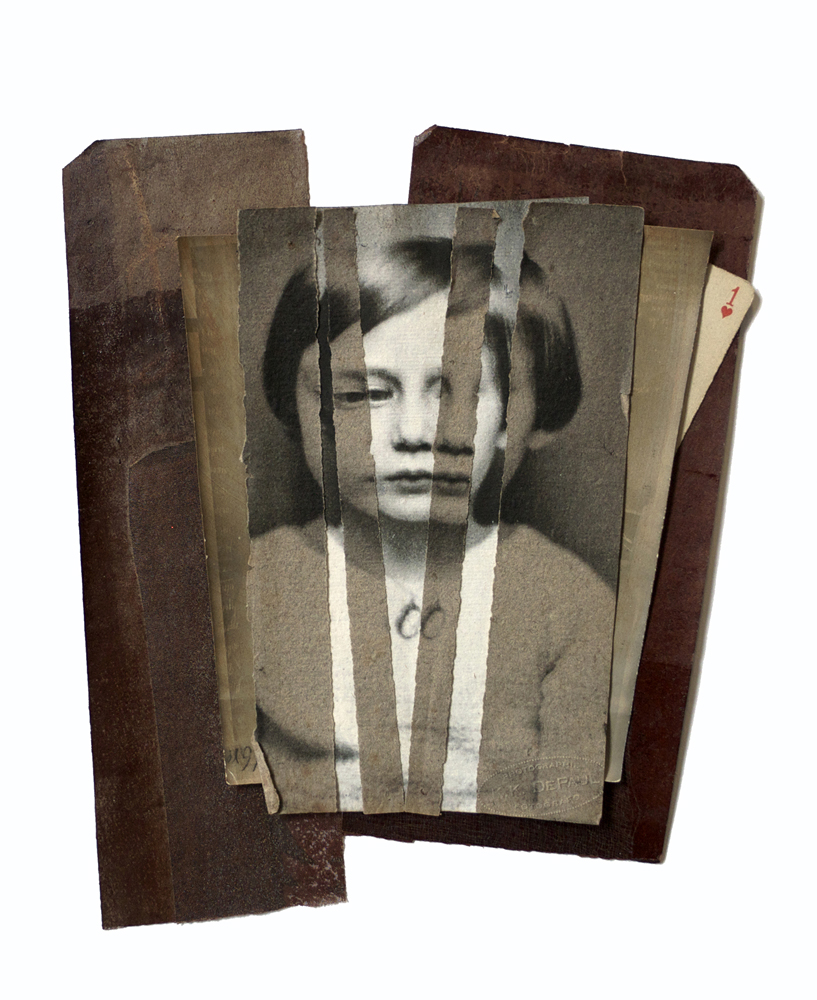

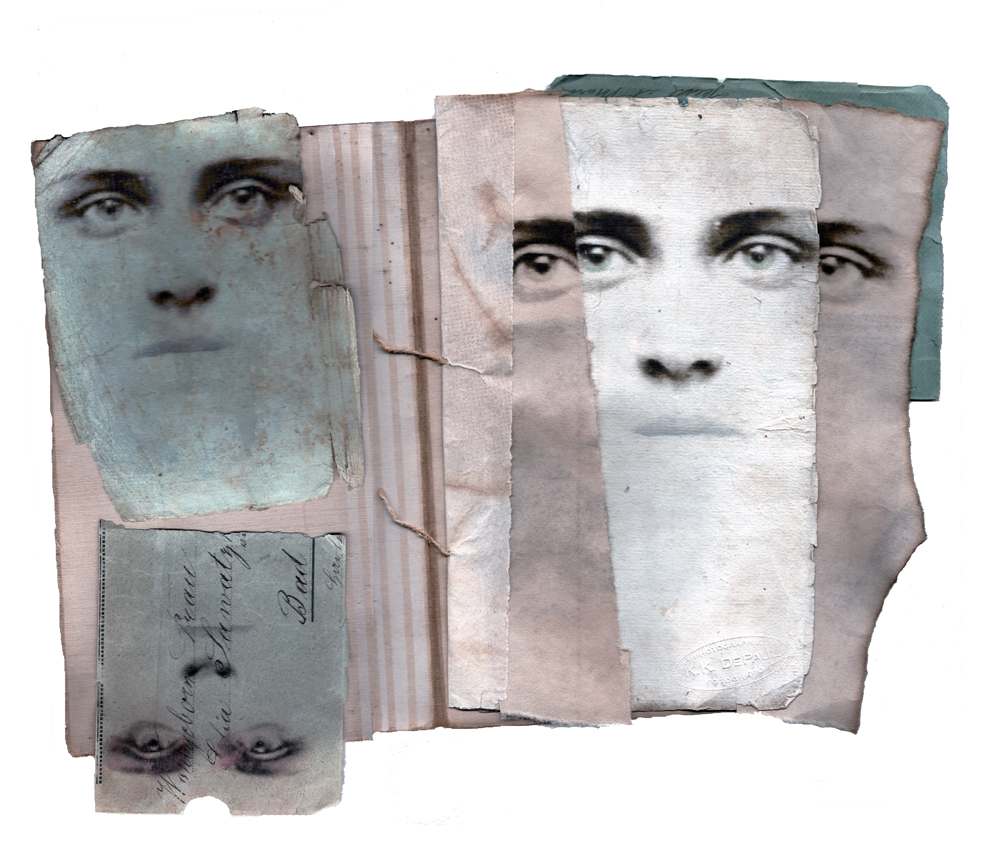

For 30 years, I was a contemporary quilt-maker. When I switched to photography, I used to think that I was changing media. Now, I understand that my process has always had to do with tearing things apart and reassembling them.

When I was in grad school, one day my advisor said to me, Kim, just because you’re in a photography program doesn’t mean you have to make traditional photographs.

Those words opened a whole new world to me and from that moment I began to embrace collage, assemblage, and the use of found photographs. Interestingly, my knowledge of sewing construction has aided this transition, and the work that became about memory and family, and is full of pins, thread, and linen.

KKD: Vicki, can you speak about skills in a former career that led you to your current art practice

VRR: I worked at a daily newspaper in a small Midwestern city and it probably was the most valuable experience I have had. It encouraged me to develop my storytelling skills and because it was a small community without a lot of breaking news, it forced me to develop my eye. I needed to find and capture the extraordinary in the ordinary. I was always looking for unusual angles or approaches to my subjects. I had to be on the lookout all of the time for patterns, shapes, lines, contrast and unusual light as well as people or happenings that might be interesting subjects for a feature story.

This was before the digital age so it also provided invaluable wet darkroom experience. Because we worked to a deadline and the editorial staff trusted me, I printed and reviewed my own contact sheets, quickly choosing the images to pass on to the managing editor for consideration. All valuable experiences that benefit my current work. Today, I still try to find the extraordinary in the ordinary and I am always looking for the one image that tells the best story.

VRR: I have a degree in psychology and I see that you have a degree in art education. When it came time for me to look into an advanced degree I decided I wanted to try something hands on before diving into the long academic road of a Masters Degree or PhD. The local vocational college had a program in Industrial and Commercial Photography and because I had been interested in photography for quite a while, I signed up. When I saw my first print slowly appear in the developing tray in the darkroom, the magic of it had me hooked. In 2010 you received your MFA in photography at Maine Media in Rockport, Maine. It had been several years since you received your art education degree. What prompted you to pursue photography?

KKD: My undergrad major was in Art Education, and so I had a smattering of education in a lot of different media. I am embarrassed to say that I got a ‘D’ in Photography. Mostly because the class was at 8 am, and I was 19, and I liked to sleep late. The approach of my professor was all about F stops and gray scales, which never have interested me.

But that ‘D’ always bothered me. So, when I was 40, I went back…same college…same professor.

This time it was different. I had time to experiment…I hung on every word…I had the money to buy unlimited paper…It was one of the best times of my life. The professor wrote me a note afterword saying that I was an inspiration to his students. I felt vindicated, and I ‘allowed’ myself to continue with photography.

Ten years later, the year I turned 50, all my hair fell out. Eyelashes…eyebrows…every hair on my body. A friend suggested that I photograph myself. I refused, thinking I don’t ever want to remember this time in my life. He told me that ten years from now, I will want to make sense of this, and that I should have a record. So one day, armed with my camera and tripod, went into the bathroom with a roll of Scala film (B+W slide film)

I did not send the film off to be developed for a year…until my hair began to grow back.

One of the most memorable moments of my life was the moment I lifted that first slide up to the window. The emotional power of that image took my breath away…and I though…OHHHHH….PHOTOGRAPHY…STORYTELLING…

My hair had been black, and when it grew back it was white….positive/negative… I saw that as a giant finger pointing me to a life in photography.

KKD: One summer, many years ago, I was in an alt pro workshop. I spent the greater part of a week trying to print the perfect Kallitype. It was causing me a lot of stress.

In the evenings, I took the ‘imperfect’ prints back to my motel room and watercolored over them. In my mind, these were throwaways…so wasn’t worried about messing them up. I was having fun.

After a few days…I printed the ‘perfect’ Kallitype. As I compared it to my ‘loser’ prints, I realized an important lesson:

Sometimes the ‘imperfect’ image tells the story better. My work is about flawed people and shattered identities…Imperfection reflects my narrative.

Although I identify as a photographer…my interest doesn’t have to do with camera types, film types, or digital vs film.

I am first and foremost a storyteller…and anything that will help propel my narrative is fair game.

I am not a purist…I use film, I use digital, and I use alt pro hybrids of the two. Sometimes I use a camera, sometimes I use my phone, and sometimes I use found photographs and objects. I use paint, pastel, and pins.

For me, crafting a compelling narrative is the only thing that matters.

KKD: Vicki, I have found that the artists who embrace alt pro, are extremely interesting people…in many cases, ‘rule-breakers’.

How does your process reflect your narrative?

VRR: Oh my. Tell me I can’t do something and I will immediately try to figure out a way. I don’t like someone putting boundaries on me in my life or in my work. It took me a while to find what I needed in alternative processes. After twenty five years in a traditional wet darkroom I was bored. It had become too predictable for me and I felt that my narrative had changed. I was more interested in capturing a mood rather than a perfectly accurate rendition of what was in front of my lens or eye.

I took my unused Diana camera out of the cupboard, bought a Holga camera and then took a Lith printing workshop from Tim Rudman. Neither the cameras nor the process were very predictable which made me excited about creating images again. I was having great fun and it felt like a new world had opened up for me, that there were no boundaries with alternative processes.

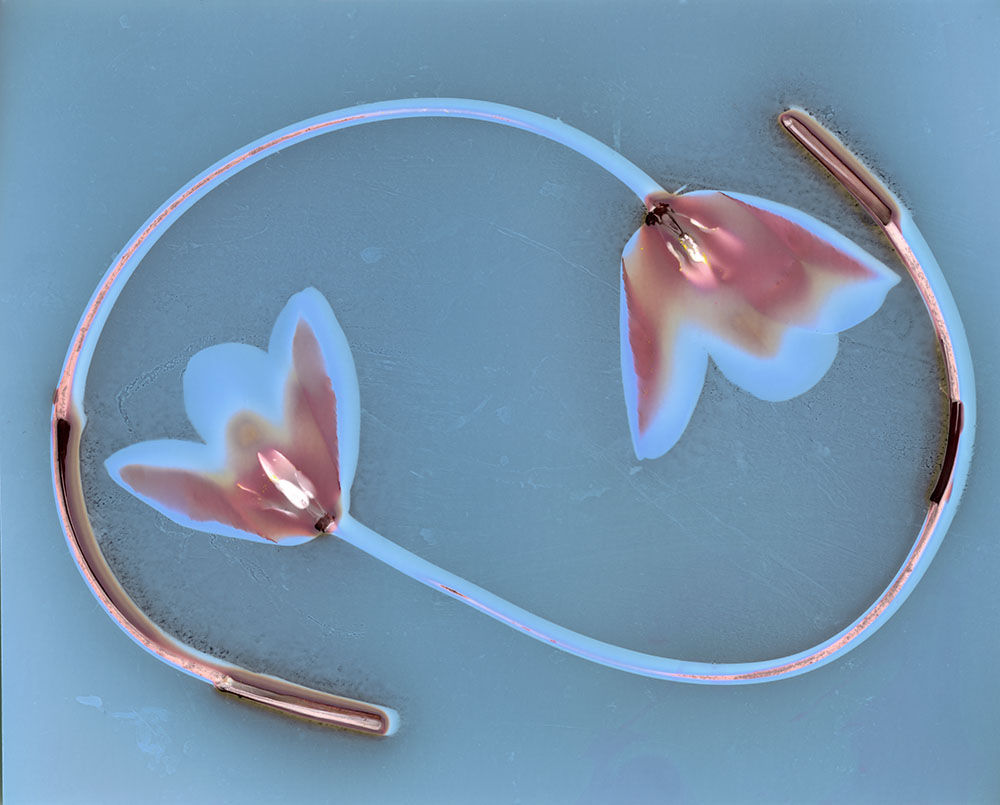

Since then I have continued exploring different processes and camera-less techniques. I feel I have many more options available to me to tell my stories and like you, I am willing to use them all. Cyanotype is what is working for me at the moment in my pursuit of exploring memory, but I will probably move on to another process at some point if it better suits the story I want to tell. I have learned to be patient and let the ideas and processes unfold and come together. I still believe it is good to understand the rules before you start breaking them. I would not be doing what I am now without having had solid technical knowledge to build on.

Vicki, I remember the day we met up at the Lancaster Farmer’s Market, and our ongoing conversation about dealing with the decline and loss of our parents. Can you speak about how your family projects have aided the mourning process?

My mom suffered from Alzheimer’s and my dad from dementia so the mourning process for them began long before they physically left me. It took me a while to recognize what was happening but once I did, it was devastating.

My photography has always been therapy for me. I love grabbing my cameras and hopping in the car to wander back roads, silently paddle in my kayak, or walk in local parks. When I am in contact with nature it soothes me and restores my spirit. It allows me quiet time to process what I am going through while at the same time, I can experience some beauty and perhaps have a little hope. It forces me to pause and appreciate what is around me.

My concern and care for my parents greatly impacted my photography in that I could no longer concentrate or spend long hours in the darkroom. I needed to be available to drop everything to go to them all hours of the day. I became aware of how precious time was and I wanted to preserve that time in some way through my photography.

My parents loved working in my gardens and theirs and like me, enjoyed going for rides. I began making lumen prints from flowers in both of our gardens as well as using plants we picked while out on our drives. It was not a deliberate thing on my part but more an unconscious act of desperation to capture something of our time together. As their memories disappeared, I tried to preserve moments of shared times in our gardens and outings through making lumen prints. The lumens needed little attention from me and could be left out for an indefinite time in the sun so if I had to leave to go care for my folks, the prints would be fine. It was the perfect outlet for my anxiety and sorrow. This work became part of my series, Ghost Garden, the deteriorated remnants of the plants in my images not unlike the memories fading from their minds. I continue to create lumens today almost two years after they both passed.

Ghost Garden was only the beginning of family based projects for me. Since then I have worked on What We Leave Behind (cyanotypes on fabric, including life size portraits of my parents with things they left behind in their move to a nursing home), Take Me Home (a series of road images representing my mom’s constant plea for me to take her home though she no longer knew where home was), and most recently, You Can’t Go Home (a series re-photographing old family photographs in their current settings).

All of these family projects are therapy for me, my way of dealing with loss. In the most recent series, You Can’t Go Home, some of which I photographed with my brother when we were back in our home town for my parents’ memorial, it provided a wonderful time for us to share memories with each other as well as with the gracious people who now own the old family homesteads. Mourning is an ongoing process and now through these projects can provide peace and even joy.

KKD: Yes, Dementia can be heartbreakingly cruel. My mother and I were very close, and she was sharp as a tack until her early nineties. And then her personality began to change…she became angry and belligerent…it was like a stranger took her place. I know now that she was scared. She said to me, “Kim, I feel like something is wrong and I think it will never be right again.”

I wanted to scoop her up and tell her everything would be OK, but I was losing little pieces of her every day.

I tried to begin a project about her soon after her passing, but it was too raw…too soon. Her decline was not an abrupt break, but rather an unraveling. I want that to be reflected in this new work.

It’s been almost two years now, and when I look at the amazingly poignant photographs I made of her on her deathbed, I finally think I’m ready to begin.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Sirkhane DarkroomMarch 26th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024

-

European Week: Steffen DiemerMarch 6th, 2024

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The Reluctant CaregiverFebruary 26th, 2024