Sarah Palmer: A Studio of One’s Own

I have never actually met Sarah Palmer. But I am a huge fan of her work, which I found on Instagram, because we have shared students over the years. I taught at a foundation program for Pratt in upstate New York and she picked up where I left off down at Pratt in Brooklyn. I saw the intensity of color and complex use of the picture plane and was intrigued beyond those things by her subject matter. When we spoke on the phone we effortlessly filled an hour on everything from teaching pedagogy to Minecraft. Though for purposes of length and focus, I give you our discussion on her work.

Sarah Palmer was born in San Francisco and lives in Brooklyn. She received her BA from Vassar College in English and Italian, and her MFA at the School of Visual Arts, in Photography, Video, and Related Media. She was awarded the 2011 Aperture Portfolio Prize and has had solo exhibitions at Mrs. Gallery (2019-20), NADA Miami with Mrs. (2019), Aperture (2012), and The Wild Project (2010), all in New York. Her work has also been exhibited at the Foam_fotografiemuseum in Amsterdam, which holds her work in its permanent collection; the Lishui Photography Festival, Lishui, China; and SPRING/BREAK Art Show in New York. Her work has been published in recent years in The New Yorker and Vice Magazine, and the books n e w f l e s h and The Photographer’s Playbook , among others. She has been publishing an ongoing series of artist books since 2015, most recently including The Sweets of Pillage and Slipping Rose. She teaches photography at Parsons School of Design and School of Visual Arts.

385 W

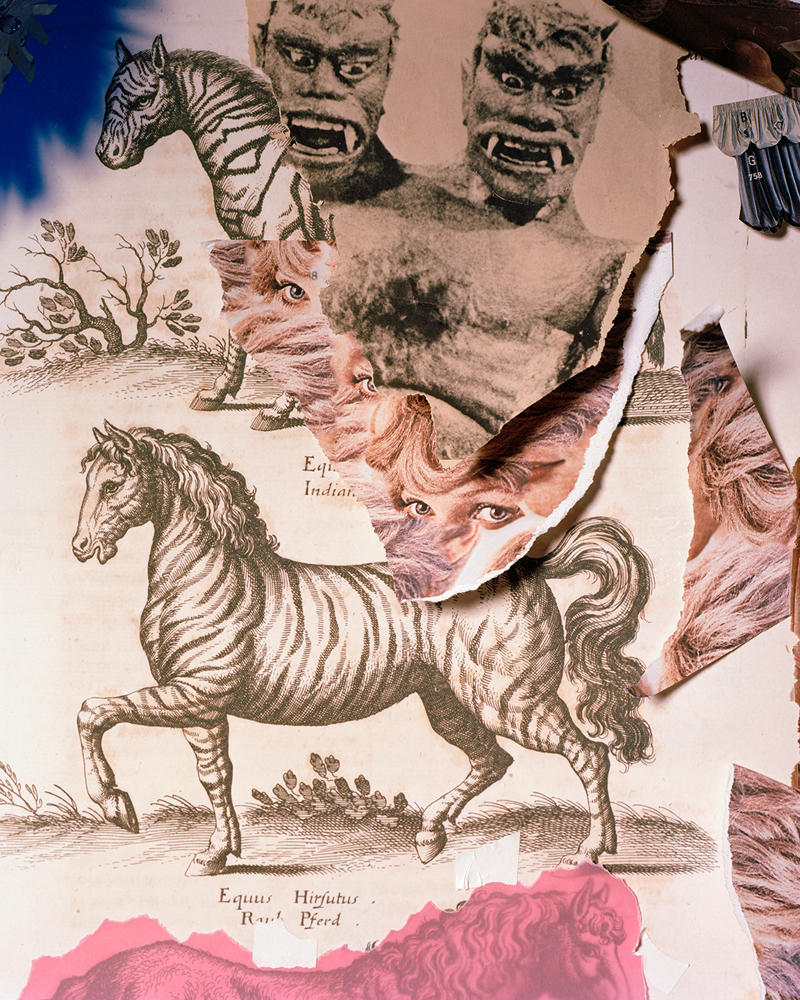

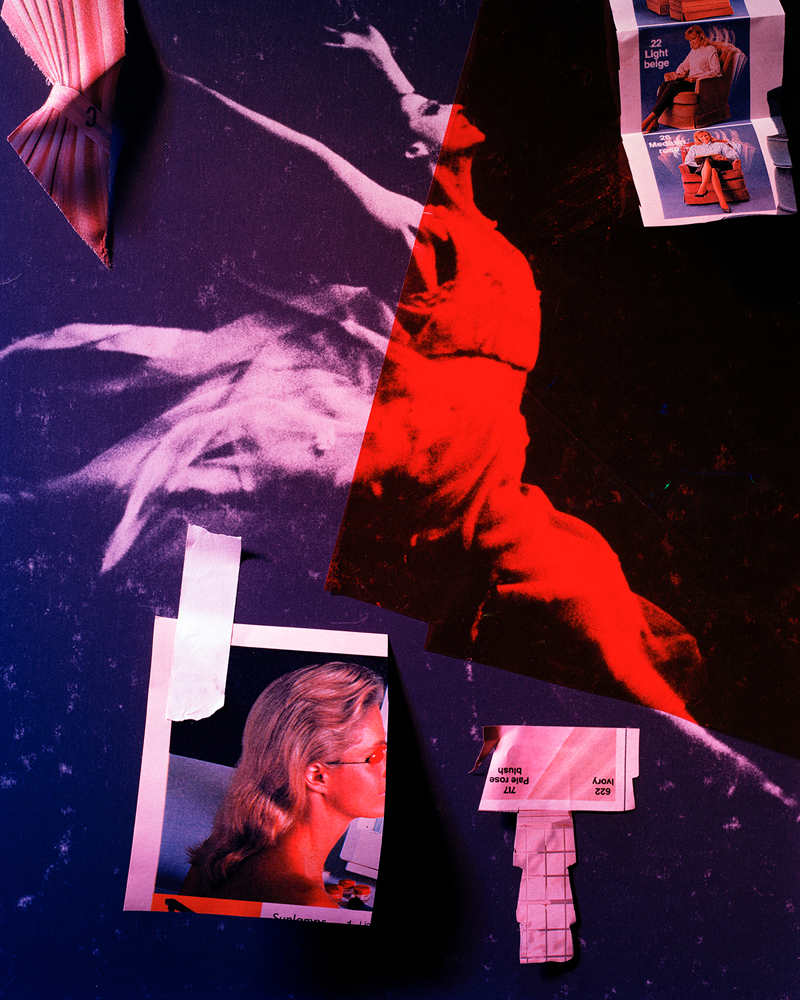

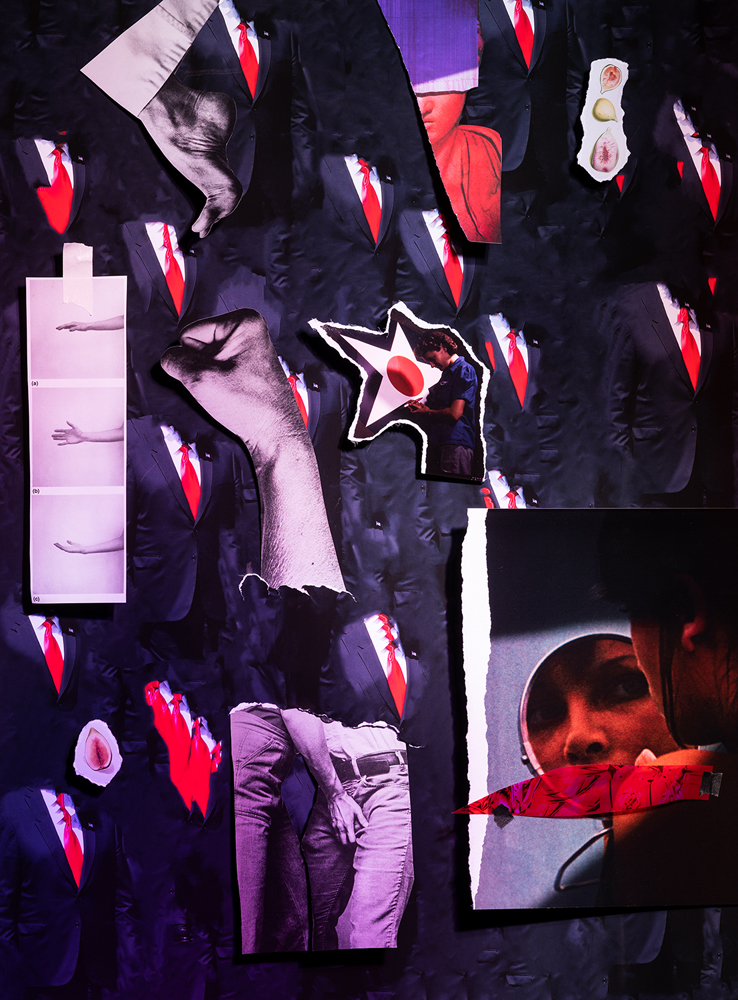

These works are sourced from my series Rose with Nails for Petals and Reaches of Salt (2018-2019), and recent series, The Book of the Living and We Exist as Wind , both ongoing and begun in 2020. These works combine images shot on large format negative and digital photographs, and explore the fraught territory of human and environmental vulnerability. Taking as their primary sources a wide variety of contemporary and historical images that serve many contexts, these isolated gestures point to our current uneasy political, social, and environmental state. Using certain images to hide and reveal others, I create tableaux of a sort whose unfolding ideas and obliquely narrative.

I build these tactile, dimensional images through a process of printing, juxtaposing, photographing, re-printing, and layering. Through recontextualization, I hope to interrogate the “performance” intrinsic in photography. I photograph these assemblages using strobes, gels, and handmade cuculoris, emphasizing their theatrical narrative. I explore how recontextualized gestures highlight the ambiguous nature of communication in an era of anonymity.

In addition to the subject of the works, their form and face are also significant. There is a rich depth to the photographic “surface,” and I examine the relationship between the contained rectangle and objects within the photographic substrate. I am intrigued by the implicit tension between the photograph’s flatness and the alternate flatness of my subjects, giving the illusion, in instances, of elements that appear to rise from the surface, creating a study in layered planes.

For two solo presentations of my work, in fall/winter 2019, I created custom wallpaper, both from images found in scanned rare books the New York Public Library has made available through its digital collections. These backgrounds – one consisting of impossible distortions of 17 th -century drawings of quadrupeds and the other a wild tangle of figs and fig leaves with animals hidden throughout – emphasize the sense of layering that is implicit in the works. It is the context within which I want my work to function, in this twisted, and infinitely referential present. All of these adjacencies reference the necessary messiness and contradiction involved in the process of making these works.

My works are printed in various sizes and in a wide array of formats, including dye-sublimation prints on aluminum, archival pigment prints, silver gelatin prints, and pigments inkjet on Habotai silk.

Rita Lombardi: How is your practice different now, if at all?

Sarah Palmer: I had two shows over the fall so I was in production mode. Suddenly in February I started getting back into work and then the world fell apart so I feel like I’m just trying to figure out where I am and I think that’s true for most people. Even the steps I was making toward making work again don’t apply. Well, they sort of do but we’re in this different world and the work inevitably responds to the world. So I think I’m just in one of those periods where I’m trying to figure out where I am and where we are and taking both the fraught nature of the moment and also the tedium of the moment and combining them into something.

Rita: It sounds like your approach is very hands on.

Sarah: I felt like that at the beginning. So from March 13th until the end of March, though it felt like forever, everything felt so tense and so dark. But then at a certain point I just had to get back to working. I had gotten a laser printer so that I could do school with my kids at home and I just started using that. My work is very iterative and so I print a lot to make the work. I started printing on that, which is very different than inkjet because it prints in halftone dots so I can’t do multiple takes of the same thing because it gets nasty looking really quickly. It was helpful to have something that I could, you know, take a photograph and make a print on something at home. And then I came back to my studio.

Rita: Your work is studio based out of choice. How did you come to this mode of working? How far back does it go and have you always worked this way?

Sarah: I first got a studio in 2008 right after grad school, which was a desk in a giant shared room, like a little corner. Because I went to a photo program I didn’t have a studio in grad school, which I think is bad, that photographers don’t have studios. They get labs and shooting studios but no artist studios. I think actually having a space is really important. So I feel like I was sort of trying to find my way through working with a space in a way. I had been shooting a lot of interiors and I just happened to start shooting these little vignettes. It feels so far away right now, that was 2009 through 2011. I moved to my current studio building in 2011, and the space I’m in now in 2014.

I love making landscape work but I wanted to be able to have a little bit more control over the feelings I was building through the work. Not necessarily creating a feeling for the viewer but just putting stuff into the work, like making pictures as opposed to finding pictures. My husband and I used to take tons of, weeks of, road trips. He’s an artist too and he makes photographs and risograph books and videos. I never really wanted to shoot a lot in New York and I didn’t want my work to have to be made outside of New York and I also wanted to be able to make it whenever I wanted. It’s hard to grasp why it happened, in a sense. I think that the work still combines both things. I also have kids now, which makes road trips harder, but I began working in the studio before I ever had kids.

Recently, though, I’ve actually been revisiting my old negatives that I’d never used, of the landscape, and using those in conjunction with objects and other photos in the studio. That’s the new work that I’ve been making, which is really interesting to me.

©Sarah Palmer, The Twice-Born Reaches of Salt 2019

Rita: Considering your project As a Real House, even when you’re outside of the studio space it looks like you’re so interested in the hand, your hand, in it.

Sarah: I would say so. Whether that’s because I found something that looks intentional or created it.

Rita: There’s an arrangement of objects placed in the space. I like that sort of play with found and placed subject. I think it carries over into what you do now.

Sarah: I do too, in a way. I think it’s hard for anybody to look at their old work. It’s like reading your old diary or something. It’s kind of embarrassing. It feels like it was this different person.

I moved to a dark studio in 2011 and a friend gave us his old lights, so I started shooting with lights which I had only done for jobs previously and teaching, not my own work, and that was kind of the kicker for me. Being able to control my own light. I never saw myself as a “studio photographer,” even though I taught studio lighting and stuff like that. It’s such an advantage to control your light. Even to create natural light in an unnatural environment. It doesn’t matter, natural or unnatural. The sun is easier because it’s just there but it’s hard when there are clouds. So being able to create my own atmosphere was really important to me.

Rita: The colors you’re introducing seem super important, so charged.

Sarah: Yes, color is really important to my work

Rita: To be really broad it looks like you’re interested in Feminist ideas. Do you want to talk about that?

Sarah: I grew up in San Francisco and my parents were very liberal. My dad’s a poet who worked with dance companies and my mom’s an architect — which was such a strange thing, to be a very successful woman architect in a male-dominated field but she was totally supportive of other women and went to pro-choice rallies and they had lots of gay friends when I was a kid and so I sort of saw myself as post-feminist in this very ignorant, white liberal way.

People in grad school would ask me what I thought of myself as a woman making landscape photographs. Naively — it seems so naive now — I used to say well, it doesn’t matter that I’m a woman. But later I realized that it really actually does. It matters so much. It does affect my point of view and the way I carry myself in the world and the way I relate to other people and even the way I feel in the world with a camera, especially when people would approach me and my huge camera in the world.

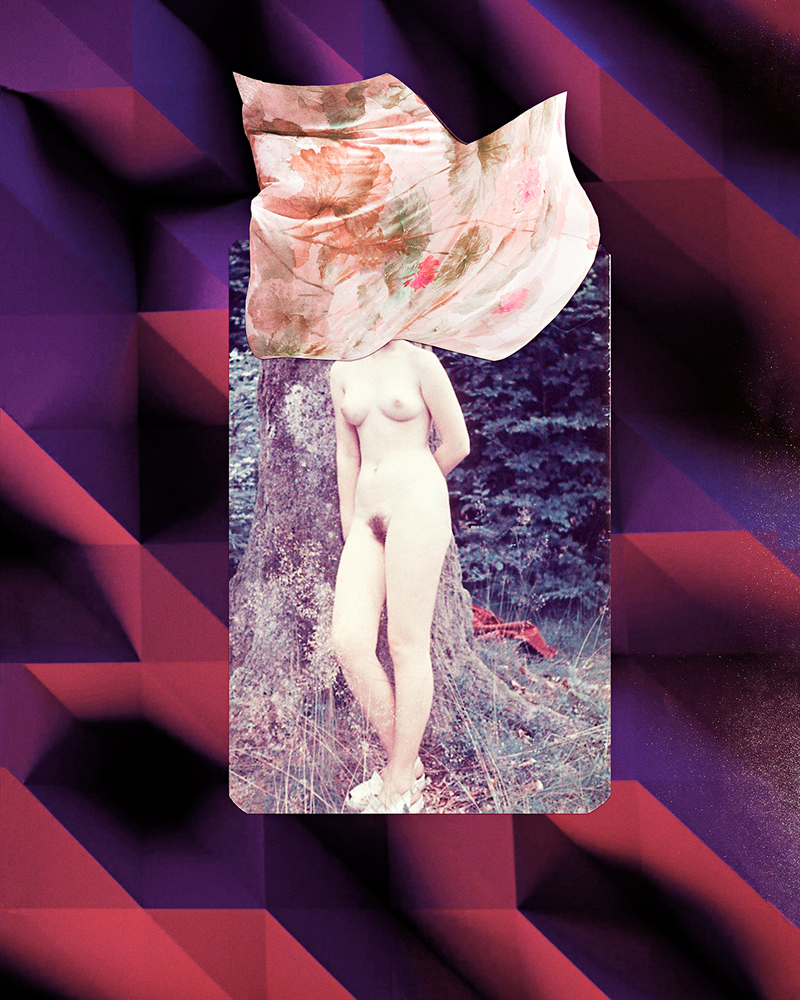

Waves, the work I started making in 2015, uses the body for the first time. Oftentimes it’s my body, not always, but often, because it’s my body and it’s mine and I’m not exploiting it if it’s mine, in a way. It feels less problematic. I don’t necessarily care whose body it is, it’s just a body. Sometimes a cut up body, sometimes a fragment. I don’t think of the pictures using my body as self portraits because they’re just kind of about the figure. Using the figure in the work became important and made the work a lot more interesting for me to make.

Rita: It certainly provides a focal point, but it doesn’t seem neutral.

Sarah: It’s about the figure, and often the woman figure but also the woman could just be me as the artist, as my point of view, the id of the work, the creator.

Rita: It seems like the bodies are almost always camouflaged. With color or things you’re placing on top of the images. I’m curious what you’re saying.

Sarah:One thing that I was beginning to explore with this work, that’s still very present and has become more actively present in my work, is the surface of the paper and the way a photograph, which provides an illusion of three dimensionality, actually is flat. And sort of the play of that. Something that is meant to create depth but has a flat surface. So you can put things on that flat surface to kind of enhance that flatness but also, by doing that, you lift up the things that are on the surface. It became this really interesting play of the surface. And I think that the human figures are easily identifiable and easily recognizable. Removing the faces in them is meant to direct the viewer away from the narrative. They’re not meant to be about this person. About humanness.

Waves, Sea Garden, and Bending the Bow are all books. I made them to be books, but also to be exhibited as prints. The repetition that happens..is almost like a wave. Each wave resembles the wave that came before it but is a little bit different. A big wave or a small wave, so a big change or a small change.

My work doesn’t comfortably fit into the realm of photography. I love photography and I teach photography but I don’t feel like I need to be in the photography world because… I think of my work as an art practice that happens to use photography and that’s not meant to be derogatory against photography or art or anything, it’s just how I view it.

Rita: The camera is the tool for you to capture the things that you want to say.

Sarah: I use the tools of photography. I use the camera, I use lighting, I use all of these things but the ultimate result doesn’t speak the language of a lot of photography. It does speak the language of what’s happening in the world of contemporary art photography. It doesn’t clarify anything, it doesn’t provide narrative.

Rita: You’re taking photographs that are sort of found and partly made out of your own work and combined…It’s not collage, it’s sort of this other level or layer

Sarah: It’s also not fixed like collage. This is the challenge in speaking about the work because I start to double down, like no, they’re photographs. The final pieces are straight photographs, they’re not manipulated, many of them were shot with a 4×5. They are very much photographs. One reason I came into the studio and just started making books and retreated from portfolio reviews and the photo network is that I would have these very unpleasant conversations with people in the photo world who would call my work multimedia and stuff like that. Without knocking multimedia work, it’s a photograph of two pieces of paper and a rock, it’s not multimedia.

Rita: It goes back to that old Magritte painting, This is Not a Pipe. It’s not a rock, it’s a photograph!

Sarah: I think that’s the perfect way to speak to it. It has the same amount of truth and illusion as any photograph, it just has a different subject matter.

Rita: Right, the illusion is just more apparent.

Sarah: It’s a mistake to read a photograph as truth anyway.

What many think is a fluency of image is just a familiarity with images and I think that’s really a challenge for photography right now. We talk a lot about it in my classes. Why would you study photography when everyone has a camera and everyone thinks they have a very sophisticated literacy with images.

I think it’s a problem. We have a photography problem. There’s too many people trying to make beautiful pictures, and beautiful interiors, washed out white millennial interiors. That kind of stuff. But I think it also kind of frees us up to not have to represent the world, in a way.

Rita: The work you’re doing shows that. You didn’t take it with your I-phone.

Sarah: Or maybe I took part of it with my iPhone but who cares.

Rita: That is something I’ve found really freeing. After the mindset of undergrad being, “it doesn’t count unless I shot it with my 4×5” and now I’m like, “whatever, it all counts!”

Sarah: Right, whatever! I think that is really freeing. It took awhile. I was very upset when my first film stock that I loved went away and Polaroid went away then Fuji instant 4×5 went away and Fuji instant medium format and everything! So I finally went, you know, screw it. I can use anything and everything. There was a period where I was cropping all my digital work to a 4×5 aspect ratio and then I thought, “Why would I lie?” They make more sense long, they’re these panoramic pictures, why would I crop them? They are meant to be how they are. Also I don’t care how I crop even my 4x5s. I don’t have a BFA, only an MFA. I didn’t learn the zone system. I don’t need the purity of 4×5 either, I just use it as a tool. So if something needs to be 22.5×31.25, that’s the size it is. And everything is exhibited together, digital and film.

Rita: That’s a very nice place to be in, mentally.

Sarah: Yeah, but it took me a while to get there.

Rita: Was there anything else we didn’t talk about that you wanted to?

Sarah: Well, I think it’s very interesting to think about how those transitions happen from working outside to working in the studio but I also like to think about how one does both. Like, I go into the world and make photographs and bring them back into the studio. I had to remind myself at a certain point that I’m allowed to also make photographs and use the photographs that I make outside.

We didn’t talk much about the newer stuff. These are using really different materials. The Waves work was like my adolescence in the studio, these later ones were really in a different place.

Rita: That’s funny because as we were talking I was looking at the new work and I felt like we were talking about it in the sense of the use of the female figure and the appropriated imagery and the lights, the way that you’re lighting things and your use of color being so strong.

Sarah: That’s good. When you realize that Francis Bacon destroyed 20 years of his paintings, I think there’s an instinct to kill your earlier selves. We try not to say kill in my house, we try to say defeat.

Rita: I’m looking at your installation shots and the wallpaper you designed really sets off the images.

Sarah: The layering is really important to the work. There’s layering within the work and then layering within the wallpaper also. So you have this layered piece in front of the background. I really loved the way the wallpaper looked but I want that even more in the work.

Rita: Seeing it installed is so different. It seems like a really big part of what you’re doing, how it lives in the space. Are you printing on silk in some of these?

Yes, there are prints on silk and also dye sublimation prints on aluminum, floated and framed with no glazing.

Rita: Not to put a label on you but if you think about the installation aspect of your artwork, is that when it feels most complete to you? When it’s installed like this?

Sarah: I would say that yes, it reflects how it’s meant to be viewed. I really like the frame because the edge is really nice, the clean edge that contains the chaos of the image. I’m really interested in the picture plane and something might be cut off but once it’s in the frame it feels intentional and finished. Then also having them at different sizes and having them speak to each other. Some are really low and some are hung really high. There is definitely a different relationship that happens.

Rita Lombardi is currently the Visiting Assistant Professor of Photography at the University of Connecticut and resides in Providence, Rhode Island. She received her MFA from The University of Connecticut and her BFA from Massachusetts College of Art and Design .

She has been the recipient of grants and scholarships, including the Innovative Teaching grant from the Wellin Museum, travel grants from the University of Connecticut and the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, the John Renna Arts Scholarship, National Endowment for the Arts. She was an artist-in-residence at the School of Visual Arts in NY and at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, CT.Her work has been in solo exhibits at the Munson Williams Proctor Art Museum, the Cogar Gallery, the Spirol Gallery, and the Dirt Palace as well as group shows in museums and galleries nationally; Los Angeles, New York, Boston, Louisville, and throughout New England.

She has been published in both print and online publications, including F-Stop Magazine, The Curated Fridge, Afield Magazine, Redivider Literary Journal, and Blank Canvas Magazine. Her photographs can be found in private and public collections and is represented in the Boston Drawing Project flat files.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026