Michael Darough: The Talk

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series The Talk by Michael Darough.

Michael Darough graduated from the University of Memphis, earning an MFA in photography in 2011. He received his BFA in photography from Arizona State University in 2007. His work explores personal and cultural identity though tableau and portraiture. Darough received a Fulbright seminar grant addressing diversity in German education, which was hosted by the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. He is a nationally exhibiting artist whose work has recently been shown at the Brooks Museum of Art in Memphis, TN, the Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, CO and is one of the Silvereye Fellowship 20 Exhibition recipients. Currently he is an Assistant Professor of Photography at Baylor University.

The Talk

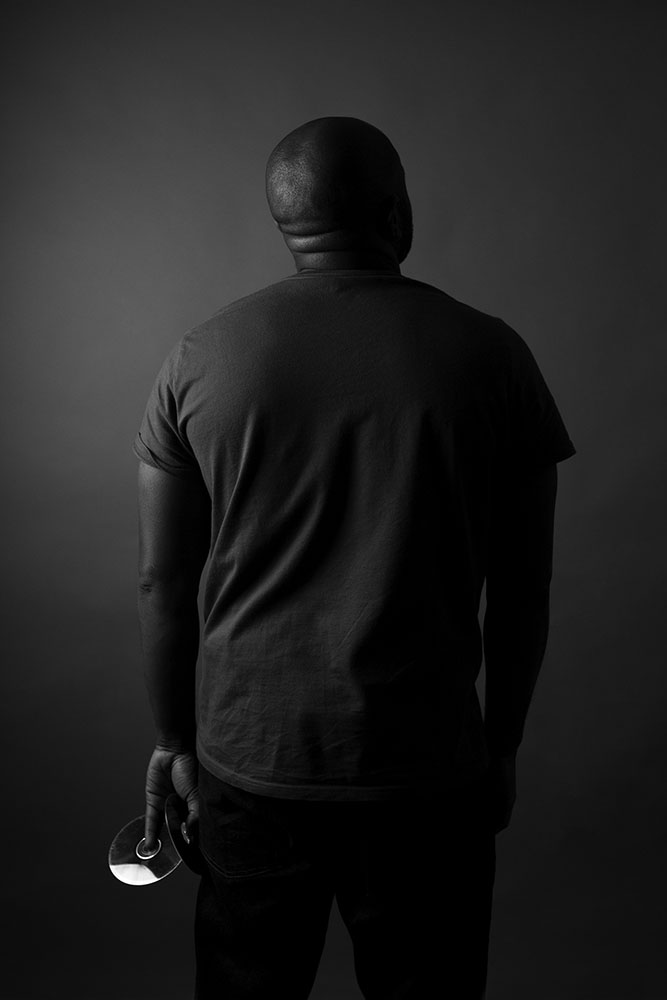

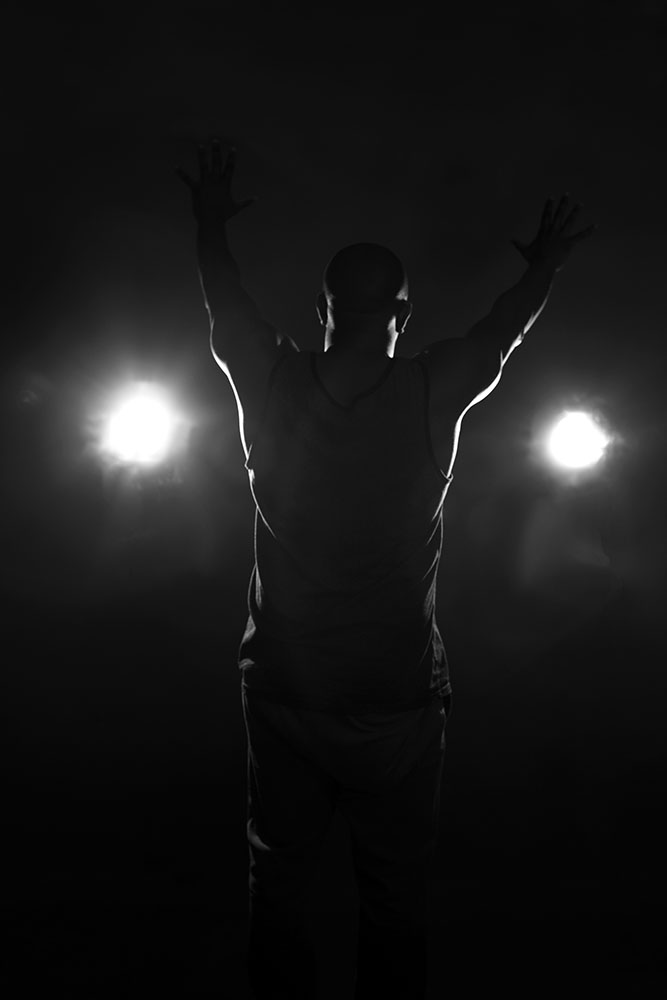

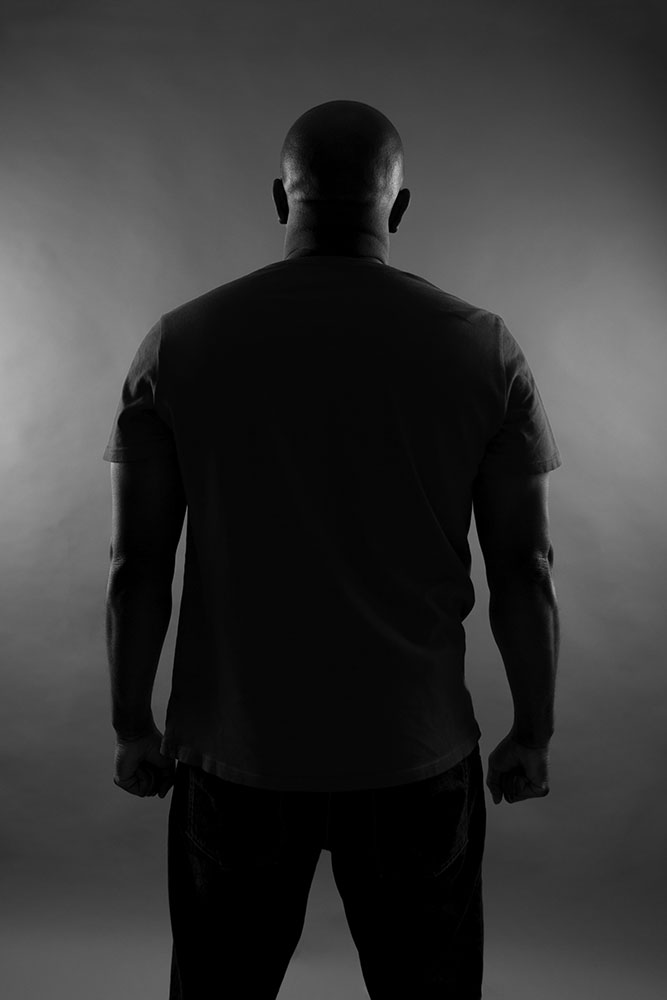

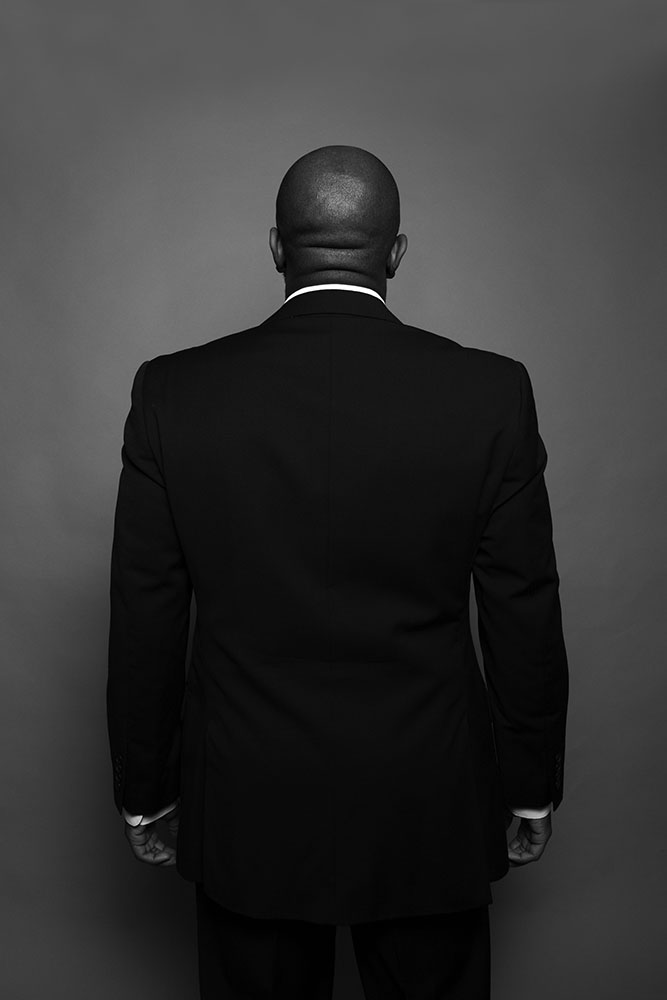

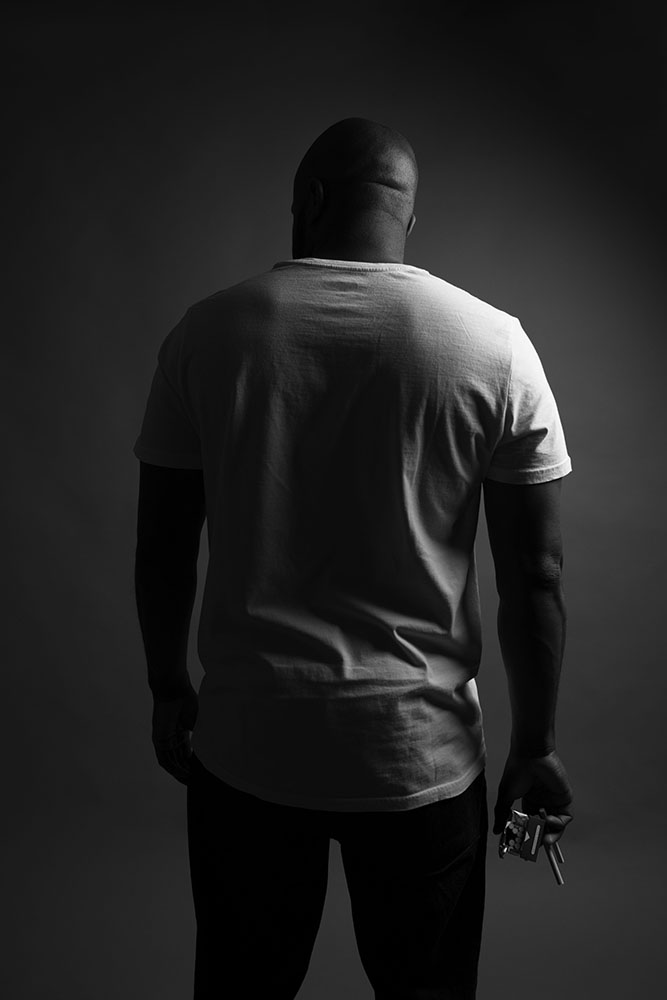

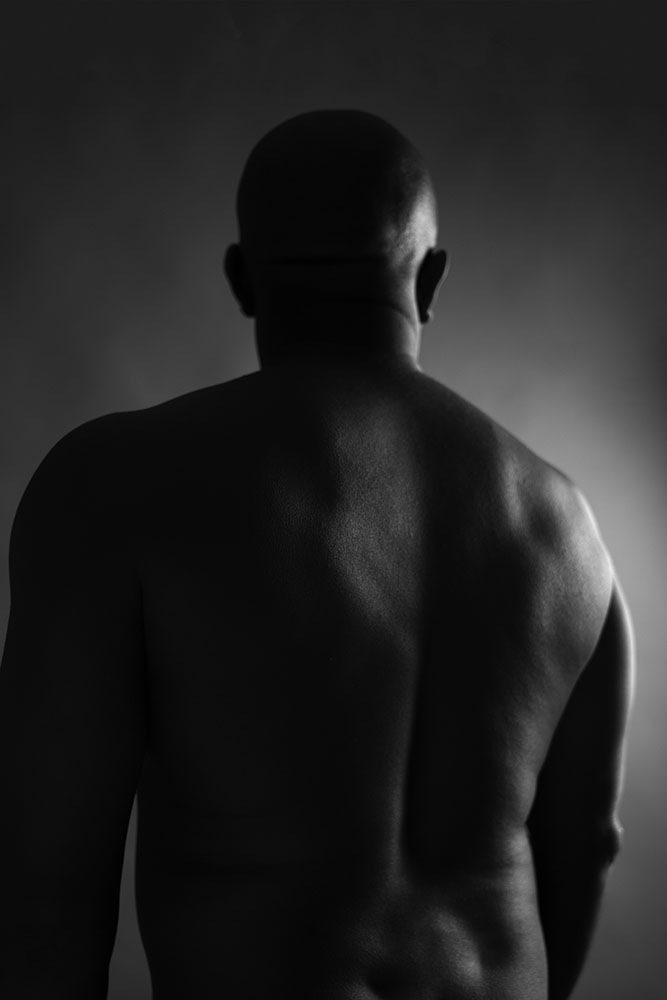

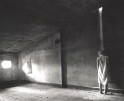

These images were created in response to the Black Lives Matter Movement. The faceless men represent individuals affected by this systemic issue. Those void of the figure symbolize the stories that struggle to be told. They are the ones that do not receive news coverage. Incarceration rates, racial profiling and fatalities from law enforcement disproportionately affect individuals of color. Police officers have the difficult task of protecting and serving our communities. They are people we depend on in common and extreme situations. I have nothing but respect for these women and men who risk their lives daily, but every black family still has to have “the talk” with their children; especially their sons. Every few months a high profile story emerges about another individual who is a victim of the criminal justice system. These situations have become all too common.

Social media and the digital age have given us access to see how excessive force has been used in several situations with individual’s of color. These problems are not new. As a country we transitioned from slavery and Jim Crow laws to segregation to civil rights. These issues went from overt to covert. Although these matters regarding race are better than they have been in decades, we still have problems within our society that have yet to be properly addressed and fixed.

Daniel George: Being that it is the title of your project, what are your memories of “the talk” growing up?

Michael Darough: The “Talk” is a continual conversation that addresses systemic racism, prejudices, and the perception that individuals may have about black/brown people as they try to navigate the world. This is a discussion that I, like many other people of color, had with my family at a very young age. It is a conversation that we’re all continuing to have today. These are teachable moments my father shared with me on early morning drives, thoughts my mother expressed before I left the house to hang out with friends, or a look my grandmother would give me as we would walk through a store together. They impressed upon me the importance of being aware of my surroundings, to understand that I am a Black man in America and the reality that comes along with that. I’m not sure if I can pinpoint a particular memory or moment because this talk has been an underlying topic in many discussions, especially in my formative years. Previous generations had some variation of this conversation. The wording and delivery might have changed to reflect the social and political climate, but overall it was the same message. I believe this current generation has the tools, knowledge from the civil rights movement, and the passion to change the nature of these conversations that we grew up with.

DG: You mention that your interests in photography revolve around the use of tableau and portraiture to explore cultural identity—often getting in front of the camera, yourself. With this particular project, why was it important for you to assume this role?

MD: I attended junior high and high school in Ferguson, MO, the same area that Mike Brown was killed. That hit home. I could have been him, and looking at how things have escalated since that incident I could still be him; I connect to these individuals. Unfortunately, as a society, there is still progress that needs to be made when it comes to valuing the lives of people of color. These deaths happen all over the country and I can’t be in each of these locations to document how it affects those communities. I felt compelled to produce work about what was going on. I walked into the studio and began the process of figuring out a different way to create photographs about this issue. Using myself as a model felt natural and a little uncomfortable as I was considering these men. Once I had the first few images, I continued to use myself as a model.

DG: Tell me more about the use of the blank frames in this sequence of images. You write that these represent the stories that lack news coverage—the struggles waiting to be told, which I find to be extremely poignant. Perhaps now more than ever, with all the videos and photographs of police violence, we are all witnesses to these events. We see the evidence, but it makes me wonder, how much goes unseen?

MD: Right now, what we’re seeing in the media regarding the treatment of people of color, particularly black men, is not new. The use of excessive force and individual’s weaponizing their privilege has been going on for years. Our transition from covert to overt is by and large due to technology. Cell phones and social media have made this systemic issue apparent to people that didn’t know it existed and has helped to validate assumptions about police violence. These high-profile cases that are presented in the news are just a fraction of the total number of incidents. With that in mind, I knew that I needed to illustrate those moments. I use the blank frames to tell the stories that the media doesn’t cover. We can’t say their names if we didn’t know that we needed to. Each of these images is titled, “Unknown Portrait”. Although they are void of a figure, they still represent people. The blank frame felt like an appropriate compliment to the others.

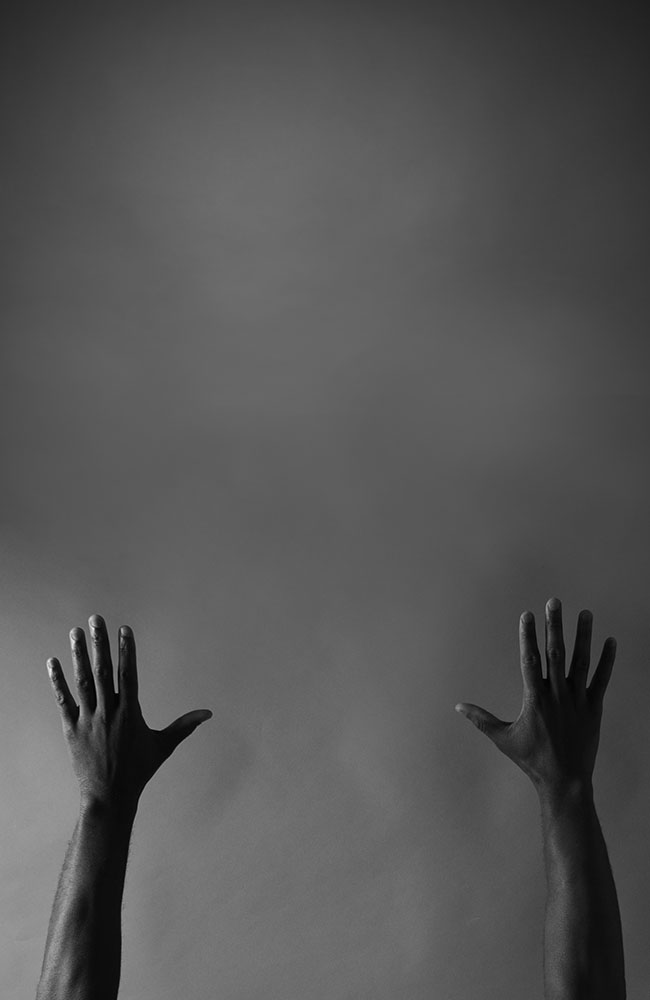

DG: After the shooting of Michael Brown in 2015, “Hands up, don’t shoot” became a slogan that continues to be chanted in protest of police murdering black people. I kept thinking this as I considered the expressiveness of hands in your photographs (even in those where they weren’t centrally focused) and the ways in which you allude to other victims, including Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, and Stephon Clark. Could you talk about your intentions with these gestures?

MD: Considering my photos are all unidentifiable men, that are representations of these individuals who have been killed as well as constructed scenarios, I can’t rely on facial expressions to change the image. I try to keep consistency in terms of the composition but allow the use of light, clothing and shifts in body language to direct the way the viewer might look at the figure. For some, I place objects in my hands that relate to their situation, for example the CD’s in regard to Alton Sterling or Eric Garner and the loose cigarettes. Changing up the position of the hands, how they might be interacting with objects or negative space helps to make the photographs more expressive.

DG: You, like many other artists, are using an artistic medium to confront systemic racism in the United States. That is a daunting task, but one that is critically important. What are your thoughts and insights into photography’s role in promoting this particular aspect of social reform?

MD: Singer and songwriter, Nina Simone once said “You can’t help it. An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.”

We are living in interesting times and it’s evident in how artists, working in different mediums, are approaching their subject matter. It is hard not to be affected by what’s going on in the world or within your own community. These factors contribute to the way we produce work and help dictate the direction of that work. I am a black artist but I am not making images about a black issue. This is America’s issue and it’s one that we need to confront and begin to resolve. Systemic racism was part of the foundation of our country and because of that it’s woven into various institutional structures. I believe that photography has a unique role in social reform because of its accessibility and our connection to it. Photography has always been considered a tool to document the truth. I believe that we have this mindset when we see these photos and videos of individuals having negative encounters with law enforcement. The images that continue to circulate around the world keep us informed and help to facilitate conversation and enact change.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Gadisse Lee: Self-PortraitsDecember 16th, 2025

-

Katelyn Lux Brewer: TICSeptember 7th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: A Mindfulness Practice with Christine CluffApril 25th, 2025