Karen Bullock: Presence Obscured

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Presence Obscured by Karen Bullock.

Karen Bullock is an emerging documentary-style photographer living in Alabama. Primarily self-taught, she photographs intuitively but has also learned much from mentors and friends. She is especially thankful for feedback on this series from Traer Scott, PhotoNola reviewers, and from Critical Mass.

This body of work, “Presence Obscured” was selected for Atlanta Photography Group’s Portfolio 2020 and Photolucida’s Critical Mass Top 200, 2019. Her series, “See Me”, was included in the 2018 Rfotofolio Selections. In 2017, she was awarded a grant for her work in portraiture by the Mobile Arts Council in Alabama.

Karen started Central ArtSanctuary in 2019, where she curated and installed the group exhibition, “Picture Your Story: Visual Storytelling with a Southern Bent”. The spring show included selected works on loan from The Do Good Fund, Inc and from individual photographers. In September 2019, she worked with local photographers Vincent Lawson & Walter Bower to put together the exhibition: “Black & White, Love & Hate: A Visual Story.” This exhibition spoke to various issues relating to prejudice, racism, gender discrimination, etc and included a panel discussion from leaders in the local community. She now works with a team to curate and install quarterly exhibitions. In 2018 Central ArtSanctuary & Central Arts Collective, of which Karen is also a member, received the Mobile Arts Council Arty Award for Cultural Innovation.

Previously, Karen was the curator for art at The Lost Garden, a community garden and outdoor art gallery in the center of downtown Mobile, AL. It was for this project that she was an Arty Award Finalist for Artistic Innovation for her collaboration with local artists in 2016. Her work is currently being exhibited in Portfolio 2020 at the Atlanta Photography Group in Atlanta, GA, and the New Orleans Photo Alliance group show, On the Line.

Presence Obscured

This series explores the shifting culture of Christianity in the American South and my own experience of faith.

It was during a difficult pregnancy followed by a miscarriage, that I felt as if God was still there, somewhere, but off in another room. That disorienting sense of presence obscured often remains years later, even as I recall times when I felt drenched in possibility and light.

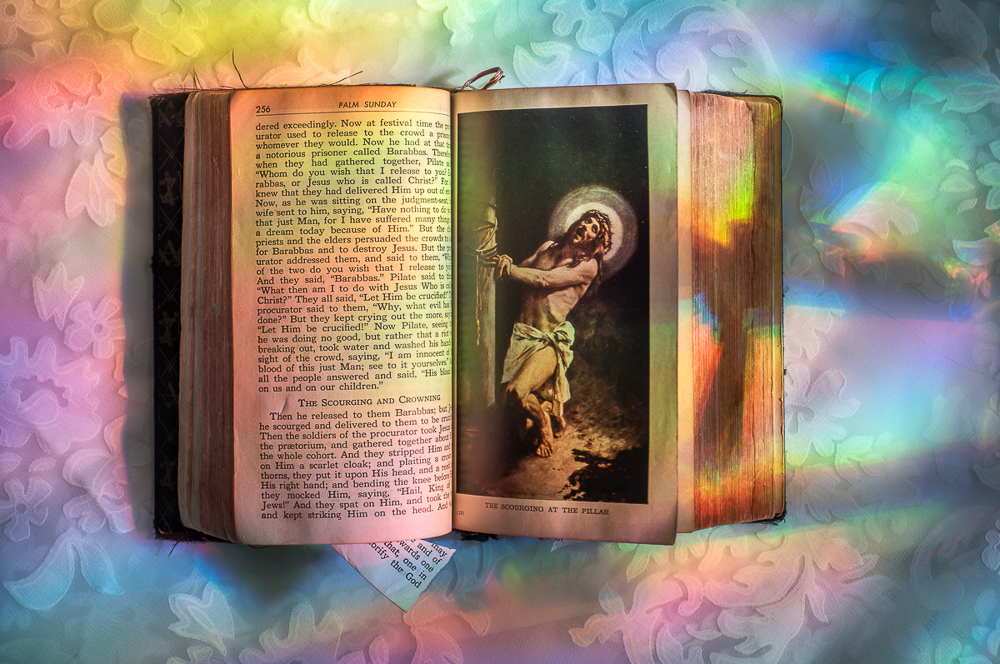

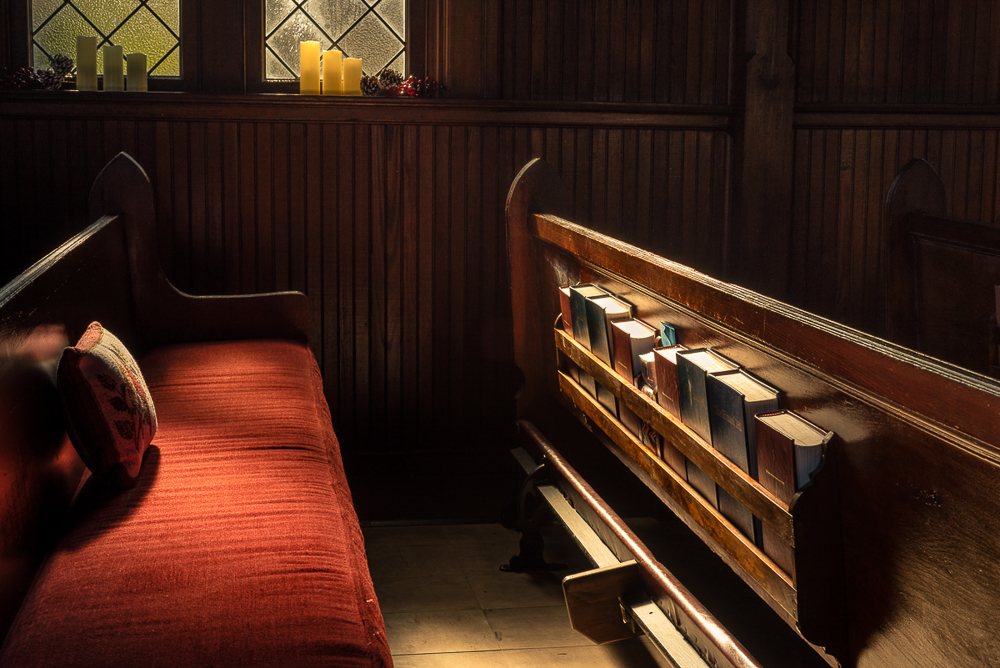

Still, I find peace when I enter an empty sanctuary, a space hushed and full of the echoes of conversations and prayers which have lingered through the years. I sit and listen to the creaks, touch the hymnals frayed from use, and experience a depth of solitude. Photography becomes a prayer.

I step outside and see reminders of God everywhere: on bumper stickers, yard signs, and telephone poles. In the wider landscape, out under the sky, I feel small and begin to think we are like little children wearing tinsel halos and catawampus wings.

A while later, I turn down a red dirt road and see the closed doors and curtained windows of an abandoned church. Will it be lovingly restored or forgotten and crumble to the ground?

I want it to be remembered as it is now, these weathered walls, this door, that humble steeple. There is something here, resilience, memory, a whisper coated in peeling paint.

“The Song of Songs” comes to my mind. It is a love poem, a story of adoration, of searching and wistfulness.

Through these photographs, I share what I perceive as an ethereal sense of presence alongside themes of longing and loss. They are an open-ended offering to the viewer to ponder experiences of faith which sometimes arise in our lives, especially in the midst of trauma or crises such as the world is enduring now.

Daniel George: This project originates from a tragic personal experience, and focuses on your spiritual beliefs. What prompted you to create and share a body of work that would render these things accessible to others?

Karen Bullock: Thank you for asking, Daniel. I was restless, feeling the need to travel, when I first saw the work of William Christenberry here in Alabama. My thoughts kept returning to his work and something shifted in me. I began to explore closer to home, in my own neighborhood and on road trips, photographing the Southern landscape, architecture, and details. I’ve always enjoyed photographing churches and, after encouragement from Traer Scott, I began to delve into that as a specific focus.

Eventually, I realized I was expressing my own sense of faith, grief, loss, and longing, through my work. It arose from a difficult pregnancy and miscarriage a few years ago.

I create photos to make sense of the world, to help me to be aware and to see. The process brings me peace. It is also a form of communication and although people have various beliefs, there is a universality to the feelings I experienced.

The project is as personal as a love poem. It is also an open-ended offering to the viewer to ponder experiences of life or faith, whatever that might mean for the individual, especially amid trauma or crises such as the world is enduring now.

DG: Your photographs focus on place, and I am interested in those qualities that you describe as “echoes of conversations.” What attracts you to the traces, or manifestations of others, within these spaces?

KB: When I walk into an empty sanctuary, I hear the echoes of my footsteps, and imagine the stories of the place. I set down my camera and walk around, run my hand across the back of a pew, notice where the finish has been partly rubbed off. I wonder who sat there; what were their joys and sorrows? I feel a sense of mystery and the reverberations of a larger story.

Here, people have wept and wailed and hugged. They have clapped and sang and rejoiced. They have shared and chatted and feasted. They have prayed.

On a good day, it catches my breath, those echoes of life—when I feel it as I walk in the door, I don’t know how to describe it—but I feel it—those are my favorite places to photograph.

DG: You mention the shifting culture of Christianity, and your images depict a very particular type of space—perhaps more traditional, or emblematic of another era. I am intrigued by the distinct vernacular of the locations you photographed, and I wonder about your interests in these, versus more contemporary places of worship.

KB: I’m intrigued too. I like the combination of timelessness and time’s passage in these places. On red dirt roads there are little churches that appear forgotten and others that are lovingly restored with consideration for historical accuracy.

Now, with the pandemic, ‘church’ is often live-streamed and people watch or participate from home. 2020 has seen a lot of change: archaic and discriminatory systems and symbols being confronted and transformed. I’m hopeful this will bring about good in the world, and in places of worship regardless of religious affiliation.

Of course, at this moment in history, the photographs will be seen with a lens unique to the present day. So, I feel the need to clarify that this is not a story about glorifying the ‘good ol’ days’. Such a time never existed. It is about my own experience, feelings that I hope others will be able to relate to also.

When I see an old church with its unique patina, I think to myself: there is something here, resilience, memory, a whisper coated in peeling paint. I want it to be remembered as it is now, these weathered walls, this door, that humble steeple.

I see strength and vulnerability, metaphors for having endured stuff in life, and the etchings of character on my soul.

DG: Tell me more about your consideration and use of light in this project. Beyond the obvious focus on religious iconography, I see light as perhaps being emblematic of individual, spiritual attestations–sometimes described as exuberant, and other times subdued. Describe your intent with these variations.

KB: I’m glad you see that. Thank you. I like your choice of the word, “exuberant.”

I prefer to find light rather than create it. Occasionally, I will use a fill light but most often it is natural light. In this series, it is, as you say, emblematic of Spirit.

Several people have said they like the ‘disco light’ in my images. That makes me laugh. I love that. I think God has a sense of humor and that is reflected in some of my photographs.

The variations of light are indicative of my spiritual experience—that from time to time the light comes flooding in and other times it is barely perceptible.

It is a way to share visually, what I perceive as an ethereal sense of presence, of Spirit.

DG: In your artist statement, you write “Photography becomes a prayer.” Could you elaborate on that statement? As an expression of faith, prayers can have various functions. I’m curious how, for you, the medium acts as such.

KB: Yes. Everything else disappears, distracting thoughts and worries are gone. Time evaporates. It is like meditation. At times, it becomes a joyful prayer of gratitude. Occasionally, it is more poignant.

This year has been a bumpy ride—for right now, that is part of it too. I am praying (camera in-hand or not) for all who are suffering, for the planet, for healing, for justice, for empathy, and for better days ahead for all. Of course, there are things that I do to address these situations. We need to do more than just offer ‘thoughts and prayers.’ But I do pray; It brings me some sense of calm.

Be well. And thank you.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024