Focus on Vernacular: The Anonymous Project

We recently talked with Lee Shulman, Film director, Founder and Curator of The Anonymous Project. He was kind enough to give Lenscratch an interview on the process of collecting photographs, building stories and entering so many people’s lives several decades later.

About the Anonymous Project: In 2017 when filmmaker Lee Shulman bought a random box of vintage slides he fell completely in love with the people and stories he discovered in these unique windows in to our past lives.

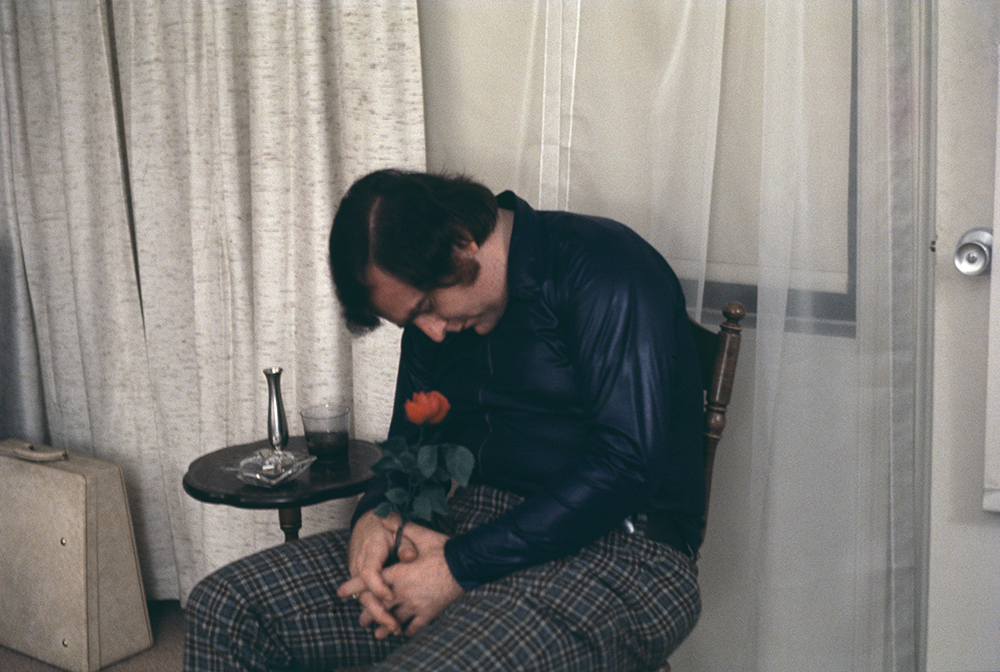

Collecting and preserving unique colour slides from the last 70 years, the project was born out of a desire to preserve this collective memory and give a second life to the people often forgotten in these timeless moments captured in stunning Kodachrome colour.

From the period of the early 1950s, when prices for color photography had dropped to where it became accessible to non-professionals, to the rise of digital cameras, color photography soon developed into the dominant medium to capture daily life. Not just weddings and graduations, or friends posing for friends, or families gathering for portraits, but everything.

The magic of color photography is that when the chemicals on the film are exposed to light, color is created. The problem is that these chemicals degrade over time, eventually leaving no trace of the image. Most color slides will not survive beyond 50 years. Unless urgent action is taken, this colorful piece of our collective memory, artifacts of daily life from the 40’s up through the digital age, will fade out of existence altogether.

These amateur photographs are a kaleidoscopic diary of that era, all the more fascinating and arresting because of their unpolished quality. Often funny, surprising and touching these images tell the stories of all our lives.

The Anonymous Project has in turn become an artistic endeavour that seeks to give meaning to these once forgotten memories and create new ways of interpretation and story telling that question our place in the world today.

This website brings together a unique selection of images from the private collection of Lee Shulman.

Statement from Lee Schulman:

I am originally from London. Like anyone from London, I’m not really English. I’m a mix, and that’s what London is about. I was very much into filmmaking because with my father I used to hang around sets: “this is what I want to do, this is fancy”.

I got into a major film school when I was like 24, 25, which was young at the time. And literally as I got out of film school I got the break of my life, one of those things. I shot a short film, and I got loads of awards, and then all the producers and the production companies called me up. At 26 I was only shooting music videos and ads, so pretty young. But I was lucky because I was shooting good advertising. In England advertising is fun, and it’s short film, and at the time we did it it was great.

I have a big career in that. It’s really funny, because I have this 18 year career of filmmaking. This is the first time I haven’t shot anything in a year and a half.

I am from a generation in which we went from analog to digital. Super amazing moment to live. I kind of feel sorry for all the people that didn’t get that passage. And not because I don’t like digital. I love digital, I mean, digital filmmaking saved my life. I was so lucky. I shot and edited all I wanted, life couldn’t get easier. And that was the good side.

And then, as I was making films, I was sitting in my office four years ago, and I was, I remember just thinking, my dad had just found all the slides I used to take in my first year of film school. You could only shoot slides. And the reason was you couldn’t reframe in filmmaking, you had to train your eye to take the frame. Because they didn’t want us to do negative, to print out our films. You had to learn to frame well.

And I was on the internet looking for vintage slides, and people were just throwing them away. I love slides. I started buying slides. I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing. And even as someone who takes photographs, I was like “these are the most amazing moments in life just lost”. And so it became obsessional. I started collecting, collecting, collecting.

How many photographs are in your collection?

Every time I say it, it makes feel bad, like a kind of serial killer. I think I have like 850000, I think more. I stopped counting. But they’re not all in the collection. What is actually in the collection and what I’ve chosen. The scan in the collection is only 15000, so it’s a very small amount, a tiny amount. It sounds like a lot, 15000, but it’s not that big. I go back into the ones I choose for a story. It’s how you feel, instinct, stuff like this. It’s amazing because as the project started to be well-known, people started sending us stuff, and the press were very keen about the images. I think the people couldn’t believe the images were so beautiful and were that old. Because some of them are 70, 80 years old. People don’t believe you. They promise they don’t believe you. Because the colors are beautiful, everything’s beautiful.

Would you say that the fact you went to film school made it easier for you to build stories or narratives from the images?

I still think I’m directing, I think. I consider myself a director. And it’s funny because I’m very much into contemporary art, a lot of my exhibitions are installations, in old house and sorts. And I build sets like film sets. And bringing everything that I like into that world. The filmmaking is a very big party. The idea is still editing, for me. I’m still an editor. And now everyone wants to be a director, to direct. But when I wanted to be a filmmaker, I was told “whatever you do in film school, don’t direct the films. You can learn how to do that. You’ll learn that. But you got to learn how to edit, the lighting. That’s what you should learn in film school”. And then editing is really what I do. It’s a very old fashion thing, to create new stories, in this way.

Have you ever came across similar styles in photography?

One thing that comes out is that I think they were very good photographers. This thing about “amateur” photographers and professional photographers is a fake argument. I think that kind of photographer now has become a lot less important than what you say in your photos. How you put together your photos, the stories you tell with them, that’s where the interesting part of life is. And that is where photographers and artists become storytellers. It’s very important.

What I noticed about them, is very interesting, because I think when we look at the images, the ones in America, and you have to remember that 80% or 90% of the whole collection is Anglo-Saxon, the majority is America. There’s a good English section, and some stuff in Europe. It was an expensive medium. But you could see, the quality of photographs in America was amazing, much better than in the 70’s and 80s. There are photographs which you look and you immediately recognize “this guy is good”. There were some photographers who weren’t really afraid to get close to the subject. And it’s very intimate. What’s amazing is the intimacy in the images, I think. Which Is funny, because lot of people think of Vivian Maier and stuff like this, but she was someone I really admire only because she would get really close to the subjects. And sometimes I’m shocked about how intimate these photographs are. There are people who catch amazing stuff in life.

I have to say the English are very different.

In America was postwar, people were very chic having fun, it’s the American dream. But behind that, there are a lot of cracks, which is very interesting in the American stuff. You see that the african american territories have changed, and are very poor, now.

Take one lot and go back to that, see where the families are now, and do a documentary about it.

That’s why I called it the Anonymous project, because I got really interested in as much as the historical side of things. It’s not only something personal. You have it, it’s there. But I’m interested in the emotional power they have. And I think that notion of value is universal. Kids jump in puddles everywhere. There are moments in life that we share. Kind of “family of man” feeling in what we see.

Everyone dressed better, that’s for certain!

But apart from that, I feel that the emotional value is there. I think we can find ourselves in these images somewhere, at some point.

The English are quite different for the lighting. The quality of the images. It’s a lot more working class. Which is really interesting actually. And they took pictures to document their lives, rather than just kind of like. The American stuff is a lot more celebratory. You know, “we’re going on a holiday, and it’s fun”. The English stuff is not as much about that. It’s to celebrate life in general, and family, the memory of the moment. That is the idea of the shared collective memory. I get these slides and the boxes are beautifully organized. Like, people put these amazing boxes of memories. It’s really beautiful. I find the objects quite beautiful as well. I put some objects in the exhibitions, like tables, where people see the slides. I want to make that part of the experience.

Boxes arrive every week.

It is also amazing to know that from one moment to another you get really close to a person. I know their sisters, their brothers, the whole story. I feel very privileged. And you become very attached to them, they are really part of your family. You know them intimately. And the more you look at them, the more you realize we all do the same things.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026