The 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize: 26 to Watch

Every year we seek to celebrate the next generation of photographic artists through our Student Prize Awards program. 2021 was a stellar year for photography, not only with a record number of excellent submissions, but the work itself reflected deep thinking and profound subject matter that it made it very difficult for the jurors to narrow down the selections. Before we begin the celebration of our 7 winners tomorrow, we wanted to shine a light on 26 photographers that you should have (and keep) on your radar, artists who may be at the beginning of their photography journey but are already working at an elevated level, creating work that is deeply meaningful, especially in a time when change is critical. Congratulations to all! – Aline Smithson

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, Publishing Director, Senior Editor, and Awards Director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, Photographer and Publisher based in New York and London, Paula Tognarelli, Director of the Griffin Museum of Photography, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize and Shawn Bush, Artist, Publisher and Educator, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

©mk.

The University of New Mexico

To Repair Broken Skin is a photographic investigation of generational body trauma, memory, and relationship within a black queer body. Evoking a sense of dissociation, with this body of work I use myself and others around me to explore the act of opening up and the simultaneous feeling of desire and reluctance that comes with that process. Interrogating the origins of shame, remorse, and uncertainty, my investigation interweaves the self and the boundaries of relationships; platonic, romantic and all the types in between. Asexual by personal orientation, lesbian by societies warrants, my use of self-portraits convolute the landscape, challenging the views of sex, transitions, and bodily integrity.

©McKinna Anderson

The University of Florida

McKinna 27 (less than a mile away).

Hi,

Let’s get a drink. We’ll chat, it’ll be weird, it could be fun, I might just wanna take your photograph.

But now we’re living in a hell-scape so

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

—

Isn’t it curious, the fact that you can always find me here. My name found through taps that makes ‘me’ ever available to you. Preferences like age, gender, proximity and the utilization of my data activity place your profile before my eyes, and mine before yours. My thumb feels the soft vibrations that occur as I press through your photographs; isn’t that satisfying?

Behind my screen tapping through, at the same time you are too.

—

McKinna’s work presents how social media accounts function as an extension of self, examines ways in which they invite the participation of others, and critiques our intimate connection to them. Curious about boundaries between online representation and physical presence, McKinna situates her practice in the context of identity construction, social connectivity, and hyperreality.

—

I am me, but I am also all of this, and these. I am what I present to you through language, appearance, and behavior. But I also exist elsewhere, on web-based platforms proliferated with images, videos, and associations that construct my identity. I am me, but I am also these things I like, I share, I post, I send. These digital attributes are within your reach, and I deem you able to do what you will with those, because you allow me to do the same.

California Institute of the Arts

To commit to memory is work in progress as I delve deeply into my parent’s life, particularly their conservative Evangelical traditions and how this plays out within the home. The genesis for this series was a video piece, “Thank you Jesus, for what you are going to do,” I made of my mom’s daily practice of planking while reciting memorized Bible verses. After completing the video in March 2020, I questioned what does it mean for me, a queer and atheist artist, to share work about deep devotion/faith? Being on different ends of the political spectrum, my parents and I constantly straddle a wide ideology chasm yet somehow, we negotiate and bridge our differences through this project. I’m interested in how the labor of looking can be a type of active listening that leads to understanding. This has led to this in-depth series looking at their complex personhood while wading through my own position.

Through photographic re-enactments, I examine domesticity, power relations, ritual, faith, aging and memory. I look at the house as a container and how it has been marked and manifested through their everyday movements, aesthetics, and use. I’m interested in both the imprint they’ve made on the house but also the imprint the house has made on them.

Within the series, there are 4 video pieces, and audio installation, and over 150 portraits and house studies. Each portrait is dually titled. My parents and I each developed our own caption for each photograph. The top title is my parents and mine follows.

©J.A. Carney

Indiana University at Bloomington

Those Left Behind is an examination into the individual lives of my family members, specifically my Grandmother’s children, to see what bonds keep us together as well as drive us to separate. My Grandmother, Michal Louise Carney, was at the center of all our lives. She still is the center. Her death has shifted the dynamics of my family, one that I took for granted. It has changed how often we see each other, for how long, where, and in what context, and it has shifted the amount of effort it takes to get everyone together. Our connection has been fractured.

My work focuses on a struggle with loss, coping with grief, as well as the joys of being alive and the intimate moments spent with family. Those Left Behind not only shows the effects of death but also visualizes a celebration of life, and in death, the remembrance of a passed life. In capturing those intimate moments with family, as ordinary as they may appear, there is a realization of unity, of togetherness that death may change but never fully take away. It is our joys and it is our pains that keep us together, not only specifically for my family but for all of us. We are individuals but our life is not our own. Though we may believe we are alone and try our best to be alone, we share that. Roy DeCarava is an artist that captured moments of intimacy between friends and family and times of hardship for individuals. His description of fleeting moments and heartfelt scenes is something I aim to capture in my work.

Those Left Behind is my journey to understand the grief of my individual family members and my own grief. I don’t want to be alone. Because of my process of photographing and interviewing my family, I believe they feel less alone too. We’re always better together. I hope this project can be a healing component for me and my family, and the viewer can find similarities within their own family and life and find a deeper appreciation for their relationships.

©Caleb Cole

Lesley University

In Lieu of Flowers is an ongoing series of memorial portraits of the transpeople murdered in the United States and Puerto Rico due to transphobia, state violence, and neglect. Part mourning ritual and part photograph, I use the roses from my garden and portraits primarily made by the subjects themselves to create a series of anthotypes, images created using photosensitive material from plants and the sun that cannot be fixed, therefore will inevitably fade. This process is an act of devotion and extended witnessing over the course of the days- to weeks-long exposures. When I move the prints from window to window each day to keep them in direct sunlight, I spend time looking into each person’s eyes, connecting with their joy and grieving for their absence. The sun, the source of life, cannot revive them, yet the sunlight that creates each anthotype is the same light that once illuminated each original selfie, connecting us to one another. The resulting work is an examination of community, loss, time, and the impossible effort to extend both the life of my roses and the memory of these stolen lives.

©Chance DeVille

Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)

Violence, specifically against women, is an epidemic that is rarely addressed as such. In Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “The Longest War”, she writes about these alarming statistics, bringing to light just how often these life-altering instances occur. Solnit states, “A woman is beaten every nine seconds in this country. Just to be clear: not nine minutes, but nine seconds. It’s the number-one cause of injury to American women; of the two million injured annually, more than half a million of those injuries require medical attention while about 145,000 require overnight hospitalization, according to the Center for Disease Control.”. These are only the statistics that can be applied because of what has been reported, and we know the reality is much worse. This work is important to not only show the specific trials my mother has faced due to this epidemic but to bring awareness to a wider audience and the ability to continue this conversation, idealistically inducing change. Due to David physically and mentally abusing my mother, Tammy, she was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and severe Post-traumatic stress disorder. Neglecting psychiatric help, she turned to drugs and alcohol to suppress the disease. As a result of these changes in behavior and lifestyle, our relationship and power dynamic as mother and child changed drastically.

David’s Mark is not only a photographic investigation of my mother, but a tool to build a new relationship with her through documentation. By showing multiple portraits where facial expression, weight, and coherency often change, the viewer is let in on the fact that schizophrenia and addiction have become a catalyst for my mother’s behavior. Additionally, Through self-portraiture, I am documenting how these traumas have affected my body and psyche. As a queer individual who is drawn to men that resemble David, I believe my desires, intimate relationships and attractions have been shaped and transformed, mostly negatively, by these acts. The self-portraits give me agency over my body and show the viewer a direct, vulnerable, but confrontational stance in defiance of the violence done to us.

©Brandon Foushee

Pratt Institute

As the politics of my body confuse you, I am rendered either hypervisible or invisible. The black visuality described confronts surveillance and combats it with the ideology of a sousveillance. Cadence is key. Spectacle is spectacle. And for this, questions of my relationship to this image box gives me permission to invite and reserve information. Black joy, black leisure, and black introspection can be read as radical. If they are read as radical, this work is not for you. Let me exist in the gray area.

Blackness, which is to say, black radicalism, is not the property of black people. All that we have (and are) is what we hold in our outstretched hands. – Fred Moten

One of the greatest tasks of blackness as collective being has been to hold itself together in something like cohesion, to exhibit some legible character. – Aria Dean

That was based upon the fallacious assumption that I, like other men, was visible. – Ralph Ellison

©Liliana Guzman

Indiana University at Bloomington

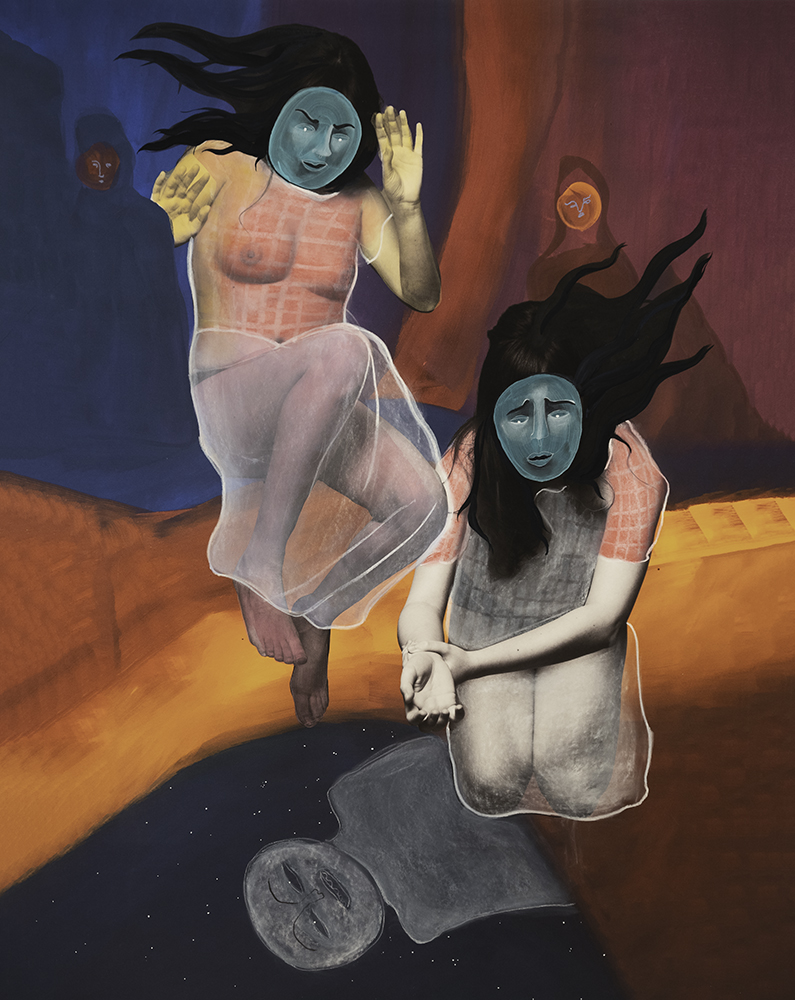

My current artwork and research, Next to Myself: Visualizing the Multiple Layers of the Latinx Female Experience and Body, combines painting and photography to reflect upon the formation of the self as an individual with social and ethnic components. Photographic elements ground the body in a concrete physical space while paint emphasizes what the mind perceives. Stemming from my background as a bicultural Colombian-American woman, this series addresses the sociocultural dualities of my exposure to different conceptions of the Latinx female body. In private family spaces as well as in religious social environments such as church or school, the body is either celebrated or restricted. The manifestation of cultural and personal dualities is one of the main threads expressed throughout this artwork.

Each piece (ranging from 30” x 40” to 36” x 48”) is a culmination of layers; the photographic print, gouache paint, charcoal, and other mark-making objects. The meaning and influence of touch and emotional performance (masks) are both prominent in my artwork. This series reinforces touch, with hands clasping, skin touching, and arms interlocked. The reoccurring use of the mask obscures the face and acts as a mechanism to compel the viewer to identify with the woman. The yellow circles are derived from the religious iconography of the halo, which is meant to signify light, divinity, and a distinct separation between the holy and the laymen and women. Not only am I interested in touch as a formative and intimate experience, but how touch plays an integral role in establishing relationships with oneself and with others. Next to Myself emphasizes how ethnicity, gender, and memory continuously build upon the many layers that make up who you are.

©Dylan Hausthor

Yale School of Art

I was recently visiting my hometown and stopped to fill up my car with gas. I noticed a woman sitting outside the gas station drinking coffee and recognized her as my old ballet teacher. I sat down next to her and we caught up. She had been going blind in the decade since I last saw her. She had fallen out of love, started growing a garden, and found god. She had a small collection of freshly picked mushrooms next to her and handed me one, saying “mushrooms have no gender, did you know that?”

Named after David Arora’s mushroom identification guide, What The Rain Might Bring is a cross-disciplinary project that explores the complexities of storytelling, faith, folklore, and the inherent queerness of the natural world.

Small-town gossip, relationships to the land, the mysteries of wildlife, the drama of humanity, and the unpredictability of human spectacle inspire the stories in these images. I’m fascinated by the instability of storytelling and hope to enable character and landscape to act as gossip in their own right: cross-pollinating and synthesizing. Class structure, ruralism, the ghosts that haunt landscapes, and disentangling colonial narratives are what drive these images and videos.

The often disregarded underbelly of a post-fact world seems to be the simultaneous beauty and danger of fiction. I’m interested in photography as a medium of hybridity and nuance—weavings of myth filled with tangents and nuances, treading the lines between investigative journalism, performance, acts of obsession, and self-conscious manipulation. Photography’s ability to promote belief is a power not dissimilar to that of faith. I hope for these images to act as tarot cards, and the viewers exist as the medium between fiction and reality—to push past questions of validity that form the base tradition of colonialism in storytelling and folklore and into a much more human sense of reality: faulted, broken, and real.

©Kylee Isom

The University of Missouri

WHERE DRAPES MEET CARPET is a series of self-portraits which navigate questions of gender, identity, and body within a constructed allusion of domestic space. Utilizing both the self-portrait and the still life, this body of work engages in conversations of representation and agency, as well as in an art historical absence of the two. WHERE THE DRAPES MEET CARPET navigates an anxiety of the feminine ideal and the complicated relationship between female bodies and the domestic space. The domestic presents as a perfectly manicured, hyper-idealistic representation of home space, consumed by nauseating plastic colors, the rashy skin of a leather couch, and the endless screaming of floral patterns. The carpet is a disorienting swath of caution orange and the drapes are a hurricane, sweeping from ceiling to floor – decapitation to the subject. The figure often renders as two-dimensional as a paper doll – a lifeless pawn to be draped across the couch like Manet’s Olympia. The diptychs stretch and distort the body beyond real dimensions, which tethers to the cultivation of beauty standards and confronts a societal obsession with the body and its appearance, past and present-day. Fragmented pieces of body lie strewn about a still life, contorting the body and questioning the equivalence of its parts. Am I no more than the mythical pomegranate of fertility? Is the flesh of my skin that of the rotten pear?

WHERE THE DRAPES MEET CARPET is an ongoing inquiry of gender normative stereotypes and the fabrication of identity.

©Camilla Jerome

Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)

It wasn’t just one accident or disease but a series of disorders that went undiagnosed and untreated. My disabled body is not a fixed state but a fluid mode of being, on a path towards deep embodied knowing, to heal the torment I have endured over fifteen years within the medical-industrial complex. Today, doctor’s bedside rhetoric are filled with modern terms for hysteria to gaslight and inflict gendered medical abuse. This form of medical trauma is endemic amongst millions of women globally. The disbelief of our suffering is drowned out by the western ideals of whiteness, beauty, femininity, ability, and health. I reclaim my voice, my self, my time, and my lived experience of being silenced and disregarded as a woman in pain, as truth.

©Helen Jones

The University of Texas at Austin

To light (working title) uses family ephemera—pictures, notes, drawings, poems—and photographs that I have taken to consider loss, time, and accumulation. It embraces many modes of photography, from large-format landscapes that attempt to show the sublime and beautiful, to snapshots, light leaks, and blown-out flash reflections. Generations of technologies speak to time—how it wears things down, the way objects gather over generations, and how their meanings accumulate and change.

The images I’ve taken to include in this project are mainly landscapes and still lives. The articles photographed include my mother’s cane, teeth, and ashes—objects imbued with meaning but photographed in quotidian settings where they now dwell. I combine more emotionally charged images like those of my mother’s ashes with humorous bits of advice or drawings of smoking creatures.

The following writing is included with the photographs; it places the photographs and ephemera within a series of landscapes and ties them to contemporary time.

I have heard it said that grief is like trying to speak underwater. True. Too, it is like floating with nothing to hold you in place. I’ve been thinking a lot about the things we drag with us through our lives, both emotionally and physically, across lands from place to place. Important things, yes, but hopelessly unimportant ones as well.

My parents both grew up in New England. Together they got as far as Arizona before turning back to settle in Vermont. When I started driving from coast to coast, my mother asked me to take her back to the southwest. She spoke of the smell of the desert at night, swamp coolers, and frying eggs on sidewalks. A decade later, we began preparing. I wanted to photograph her looking defiant in the glimmering light of the southwest. We would scatter some of my father’s ashes in Arizona. But the dusty orange box of ashes got lost in a move from one apartment to another. My mother had just gone on oxygen, and travel was hard. Instead, we drove along the southern highlands.

West through the Monongahela, two generations, whizzing past Witches Hole, Haven, Never Sink, Stony Kill. Into the wild and wonderful state, Lewisburg, Lawrenceburg, Look Out. Mammoth Cave, soda straws, cave bacon, getting soft of hotel waffles. Back east through the birthplace of country music, down blue ridges, up great smokes, past Hungry Mother, Dry Fork, Greasy Ridge, Dark Hallow Falls, Dismal Hollow, Crow Hollow, Possum Hollow, Dark Horse Lane, Dripping Lick Creek, Horse Shoe Bend, Dark Horse Lane, Wiseman Branch.

Less than a year after that journey, I was road-tripping again, driving both parents’ ashes, artifacts, and an excessive ephemera collection, back to the west coast. In rural Pennsylvania (the state that my grandparents came from before landing in the hills of Vermont), a chunk of ice clobbered my radiator, leaving me stranded at the Liberty Travel Plaza for five hours. Tethered to a lone outlet, behind the Big Buck Hunter (Safari edition), I considered what to rescue from my car before the tow truck came, watching my phone’s battery life hover around five percent, waiting for word from AAA.

Eventually, I got going again, continued through the mountains of North Carolina, over highways to the desert of Arizona, then up to the Pacific North West. I made some stops to photograph, sometimes placing one of my mother’s belongings in the frame. I’d imagined I would scatter their ashes, have some kind of ceremony, maybe, pray, or take up writing poetry; I didn’t, though their ashes sat there bucked into the front seat.

In Portland, I was living in a trailer without enough space to spread out and take stock. Most of what I had brought with me stayed packed tightly into several large Tupperware bins for another year. I went back to cleaning houses. It is a strange thing to be a house cleaner—an outsider let into a private space. Dusting around a precarious shelf, I set it wavering, toppling a cat urn off the unstable shrine. It broke— superficially—ashes staying intact, thank goodness. Cardboard, on the other hand, does not shatter. Another client, down the street, felt calmed by the sight of vacuum tracks on her carpet after a long day at work. After vacuuming each rug, I would go over it an extra time, walking backward, leaving neat impressions in stripes or grids.

These days I live in Texas, the jumbo state, and have a little more space of my own. The ephemera I’ve carted from state to state swirls across my living room floor, reminiscent of unpredictable weather patterns my father made diagrams or the beginnings of a jigsaw taking shape on a tabletop. Pieces surface for varying amounts of time before stacks accumulate on top of them. A notebook full of equations briefly breaks into understandable language “It fails It still won’t go deeper than line 107—Martha says get milk.” Scrap paper reminders from watching the landscape unfurl out the passenger window back in the Appalachians, “Black cows, red clay, grey smokestacks, lead kindly light.” I line photographs up, cars, cats, cloudy horizons, tufts of cigarette smoke.

©Su Ji Lee

Pratt Institute

The existence of an individual is defined by the space around the being. If a new system governs one’s ground, the occupancy would be defined accordingly. Here, I welcome you to Flat Space, a carefully constructed territory that questions the innate law and hierarchy of an embedded space.

This alternate universe mimics our well-perceived residency, the Earth, by including all the basic elements in the neighborhood. However, Flat Space presents an unusual sighting of ordinary objects placed in a common environment. One can recognize the materials yet the physical forces are carefully controlled in this curated space, allowing this alternate universe to create its own tension and order. The residing subject matters are also free to explore and question the innate law of physicality without any perceived restraints.

By challenging the very laws of nature, this part of the world offers a surreal yet cathartic experience to the viewers. Although the existence of the fully constructed environment is only confirmed by a series of photographs, the sightings are captured as a form of evidence of the potential utopia. Here, this platform aims to become an outlet from reality and succumbs the viewers to a visually immersive experience. By offering both of the ordered and the boundless, the collectives are hopeful to meet new audience to enter their part of the universe.

©Amber Lee Williams

The University of Waterloo

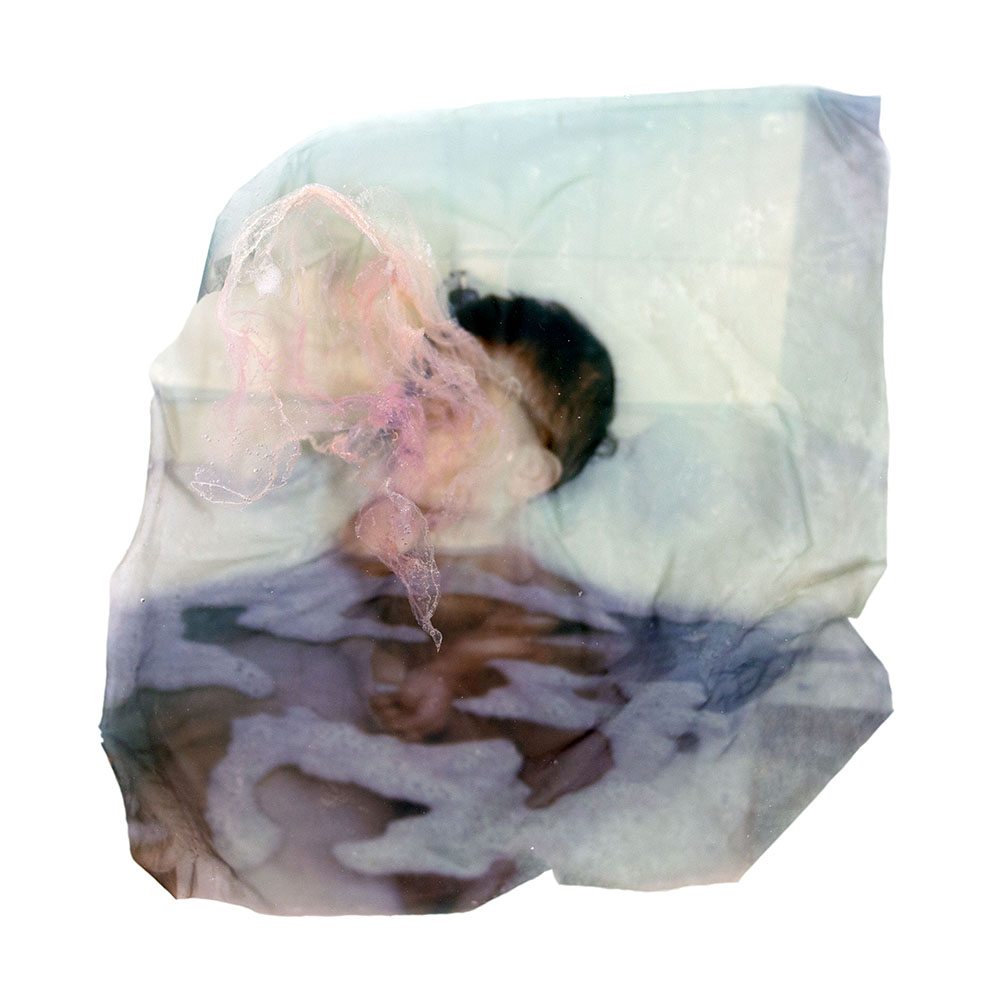

Motherhood begins with a severing. The physical connection ends and an emotional one begins. Tethered implies a connection that is no longer there, and paradoxically, the connection that remains.

This series is an exploration of the connection between mother and child and the inevitable lessening and undoing of that connection. I am drawn to simple moments or every day parts of motherhood: nourishment, growth, story time, change, the home (turned upside down), time passing (the days and nights), rest, illness, washing, all the washing, washing of bodies, washing of clothes, the folding, the time spent on the floor next to the tub, and reflecting on my own childhood and sometimes feeling like my own mother. Within the repeating daily cycle of raising children, mundane everyday occurrences often give rise to beautiful special moments.

Through self-portraits, photos of my own children, and other mothers with their children, Tethered is part observation and part documentation of daily life. This work is about moments in the home, feelings, intangible things, emotional struggles, balancing emotional and physical labour that comes with motherhood, unpredictability of children, and how little control we have sometimes.

©Vanessa Leroy, Fortune

Massachusetts College of Art and Design

There isn’t a lot of space for dreaming in an oppressive world, so I use photography as a tool to create worlds where I freely navigate the various facets of my life experience and identity as a black woman. In my senior thesis project titled as our bodies lift up slowly, I weave the viewer between the past and present using archival family photographs, text, collages, environmental portraits, and the use of both grayscale and color. Heavily inspired by Octavia Butler’s novel Kindred, in which the young black protagonist Dana Franklin navigates a shifting timeline to uncover truths about her family lineage, I employ non-linear visual storytelling as a method to arrive at similar discoveries. I reflect upon my Haitian Catholic upbringing, the effects of generational trauma, and the relationships that have nurtured my growth. I create photographs that speak to and comfort my younger self, and the versions of myself that struggled to carry the weight of having poor mental health and low self-esteem. In revisiting the past and imagining the future, I have created space for myself to heal in the present.

Texas State University

This project started in the middle of a Texas summer. While cleaning out my family’s garage, I found a letter from my grandfather to my mother. I moved from the hot garage to the comfort of my cool room to inspect the letter further. It was dated 1989, a year after I was born, and a time where the only method of communication for my parents and my grandparents was through scheduled phone calls, letters, and packages filled with photos or VHS video recordings. My father and mother were born and raised in their respective countries of Germany and Peru. They immigrated to the Rio Grande Valley, the southernmost tip of South Texas, and a portion of northern Tamaulipas, Mexico.

I, along with my siblings, are first-generation multicultural Americans. It has been hard to feel a sense of belonging or acceptance anywhere. I often question what makes up one’s identity, and when several cultures are involved, is there one that dominates above the rest, or can they all live within someone harmoniously? Growing up, it was not uncommon to hear things like “You wouldn’t understand because you’re not Mexican” or “I forgot you were Peruvian” from both close friends and family members, leading to a feeling of being othered by my communities. These feelings have led me to question my understanding of place, my sense of personal identity, and even the impressions of my memories. This project is a metaphor for the in-between– discovering a mental space that I have constructed while delving into my family’s past.

I have created a visual narrative that reflects the loss of ethnic roots, exploring the isolation and confusion felt from multiple cultures. This project consists of photographs constructed from my memories and life events. I rely on symbolism to relate to my cultures and combine them to find a new meaning representing my experience. The color red is consistent throughout my project. It is the only color that brings all four cultures together through their flags and a complex color that holds many meanings, from love and passion to anger and religious fervor. I use my family archives to explore my family’s history throughout several generations and make sense of myself.

©Owen McCarter

Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)

For the last three years I’ve been working on a project that focuses on cycles of violence in relationship to race and gender. I wanted to reexamine my childhood and young adult life through a critical lens. Questioning what it means to come of age as someone who identifies as masculine, as a white person, as an oppressor? What cultural language was I taught growing up in a small rural community? What did I learn through my family? By reflecting on these experiences and my participation in them, the project has become a process of unlearning. I think now more than ever it is essential to create work that calls for self reflection, to attempt to understand yourself in a cultural context rather than purely as an individual. To generate discussion about identity and oppression and the ways in which we perpetuate violence. My aim in sharing this work isn’t to convey exactly what it means to me, but rather to create something that people can relate to on their own terms. Find their own questions and answers within the work. It is engaging that process of questioning that interests me.

©Tayla Nebesky

The University of the West of England at Bristol

Blue Tongue is the result of an unexpected stay on my parents ranch in California. Having moved away more than ten years prior, this extended visit provided an opportunity to translate into imagery my observations of a place I know intimately.

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC)

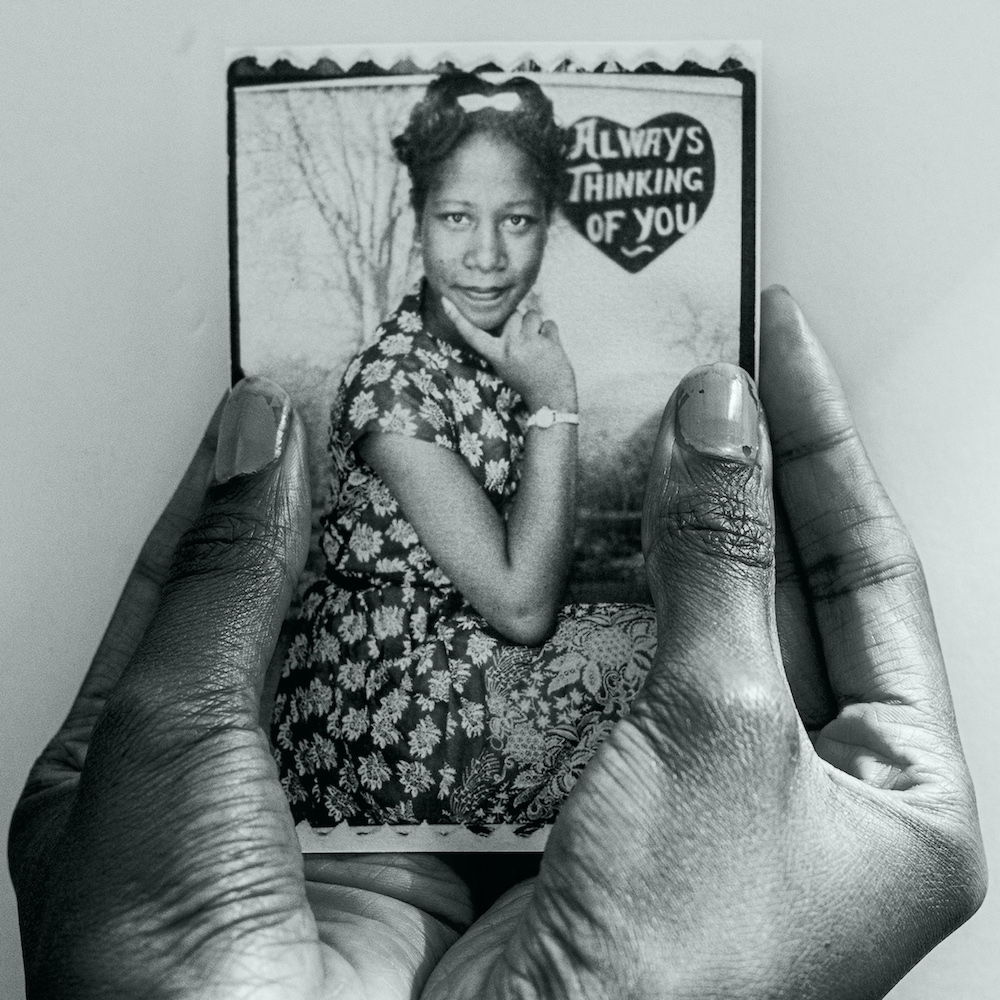

In 2020, I was feeling quite detached from creating work, and I hit a patch in my practice where my motivation to create temporarily subsided. This was a direct result of the social unrest and the pandemic. In June, I went back home to Alabama for a couple of months to be with family and rejuvenate my mind, body, and soul. I spent a lot of time between my Grandmother and my Mom’s homes, both of whom I am very close with. We went through photo albums together and loose images hanging around in tubs throughout my Grandmother’s home. It took weeks to go through hundreds of photos dating from the late 19th century to the present. This experience resulted in my attachment to vernacular images and what stories they revealed. Yet, this moment was also the catalyst to me questioning the stakes of when we are not able to speak for ourselves or lack full control over our own narratives.

Throughout history, there has been a unique curiosity to capture and study the Black body, especially those of Black women. Our bodies have continued to be seen as objects to capitalize off of and often times hardly anything beyond that. With these ideas in mind, my practice is currently revolving around two questions. What can visual art tell us about the depiction of Black women throughout history? How have those negative depictions of Black women resulted in our lack of mental and physical care?

I have spent months researching and uncovering suppressed images of Black women held in photographic collections at the Art Institute of Chicago. The images I have found and researched thus far depict the exploitation and violence towards Black women. In my practice, I have excavated, re-photographed, re-captioned, and re-contextualized the original works. By engaging with these images with the intervention of my hands and my body, I attempt to rescue and protect Black women’s bodies and their humanity, and also unearth their stories so that they can be seen and heard. With my ongoing body of work entitled Our Mothers’ Gardens, I beg for more than the visibility of Black women in institutional collections and hopeful reparations. I also desire for the issue around institutions holding and silencing collections of visible and (in)visible violent visual depictions of Black women to be further highlighted.

©Madison Prince

Jacksonville State University

Quit Squalin’ is an ongoing series that addresses the isolation and discomfort of growing up queer in the American South. Taking pride in one’s heritage while simultaneously rejecting harmful cultural norms are complex feelings that intrigue and mystify, and these images are an attempt at depicting this juxtaposition of emotions. In the empty spaces of the abandoned places in these photographs, one can feel calm and peaceful due to the quietness, however, the decaying walls reveal an unreliable structure that exemplifies the uncertainty surrounding one’s relationship with personal authenticity.

Informed by the places I visited with my family and the objects that surrounded me as a child, the level of comfort with the places and objects stand in conflict with the turmoil of being raised in a conservative household. The playful but disconnected subject exposes the internal conflict of resolving normalcy in identity in the context of southern domestic life.

©Muhammad Rakibul Hasan

The International Center of Photography (ICP)

“I grow up in terrible loneliness. I wanted to talk to someone but no one was there to listen to me. I left home knowing that no one will come to take me back. I have never lived a normal life. And love has been always forbidden” – Lara (23), a transwoman

At the beginning of hormone replacement therapy Lara faced difficulties. But she is determined to continue transforming herself. But that does not change how society views Lara. In Bangladesh, transgender people are subject to extensive daily abuse, having been abandoned by family and friends. Existing in a transphobic society is a barrier to enlightenment as a person in life. The photo story is an attempt to find an infinite and beautiful gradient of the representation of love, beyond gender identities and the reflection of their personas. The coronavirus pandemic has pushed the LGBTQ+ community at the edge. The economic crisis has put them in helplessness and survival issues.

In Bangladesh, transgender people are subject to extensive daily abuse, having been abandoned by family and friends. Existing in a transphobic society is a barrier to enlightenment as a person in life. The coronavirus pandemic has pushed the LGBTQ+ community at the edge. The economic crisis has put them in helplessness and survival issues.

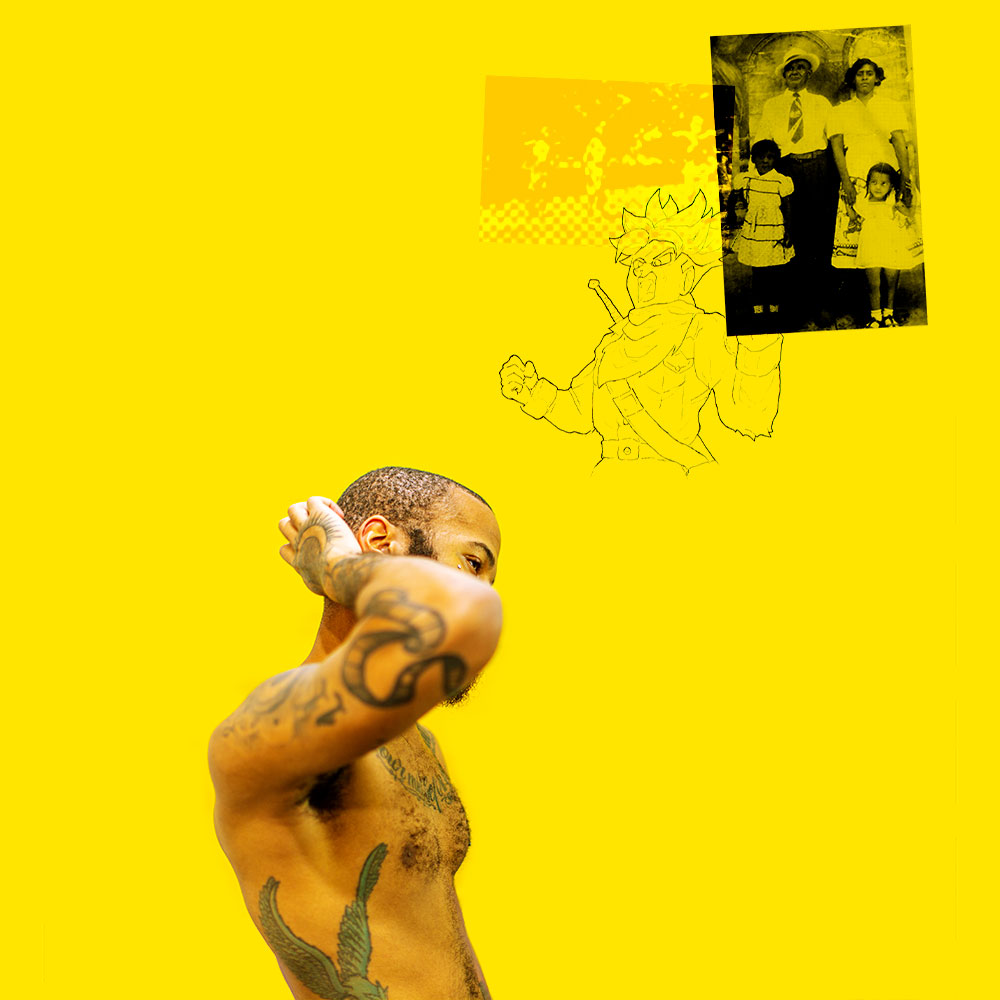

The University of New Mexico

I’ve been told all throughout my time as an academic that in order to understand the present, I’ve got to know the history. I find that funny as a Black man born and raised in America. It’s not that I disagree—it’s just that I know that my history on this land, Black history, has been distorted and fucked-up in order to perpetuate the racist repercussions of European colonialism and white privilege in this godforsaken country.

Anti-Blackness at the hands of racist America seems inescapable no matter what context I place it into; literature, science, government, health, art… look into any “field” and see for yourself. My people have had to cry, scream, and fight for respect throughout all these fields of study for centuries, and we still haven’t gained the rightful respect we deserve. Even in the visual arts, the field of study I’ve chosen to dedicate my life to, the history of racism against Black bodies runs rampant. In order to move on from this shit, we must acknowledge the many ways this country has implemented a racial hierarchy since these lands were first colonized and stripped from indigenous peoples, and Black people were stolen from their native land and brought here.

BLACK SNAFU (Situation Niggas: All Fucked Up) gets its name from “Private Snafu”, a series of cartoon shorts made in the 1940s by Warner Bros. in order to educate American WWII soldiers on the military and their warfare tactics. In BLACK SNAFU, I appropriate various depictions of Black people that I find throughout the cartooning of American history—from the 20th century racist characters in Don Raye’s “Scrub Me Mama with a Boogie Beat” to more contemporary, uplifting, and pro-Black characters like Huey and Riley Freeman from Aaron McGruder’s “The Boondocks”—and juxtapose them with photographs that line up more authentically with a (my) Black experience. These photographs are made by my hand and come from my camera, allowing me fight back against the historical racist tropes I reference with my own authentic Blackness. By combining these ambivalent visual languages, I intend to expose to viewers America’s deplorable connection to anti-Black tropes through pop-culture while simultaneously celebrating the reality of what it means to be Black.

©Tristan Sheldon

The University of Missouri at Columbia

In these times of widening political divides, a deepening collective distrust of our leaders, an ever-expanding chasm between the rich and poor, a global pandemic, and the steadily increasing frequency of devastating environmental disasters, we find ourselves vulnerable and powerless. We know that a society based on never ending growth and consumption cannot last. We must rethink our relationship with the natural world that supports us. If we don’t, then our moment here will be corrected by ecological and environmental forces outside of our control. This body of work visualizes the anxiety of living with unstable corporate and geopolitical control by exploring themes of environmental precarity, infrastructural decay, world-shaping geological forces, and the cycle of death and renewal.

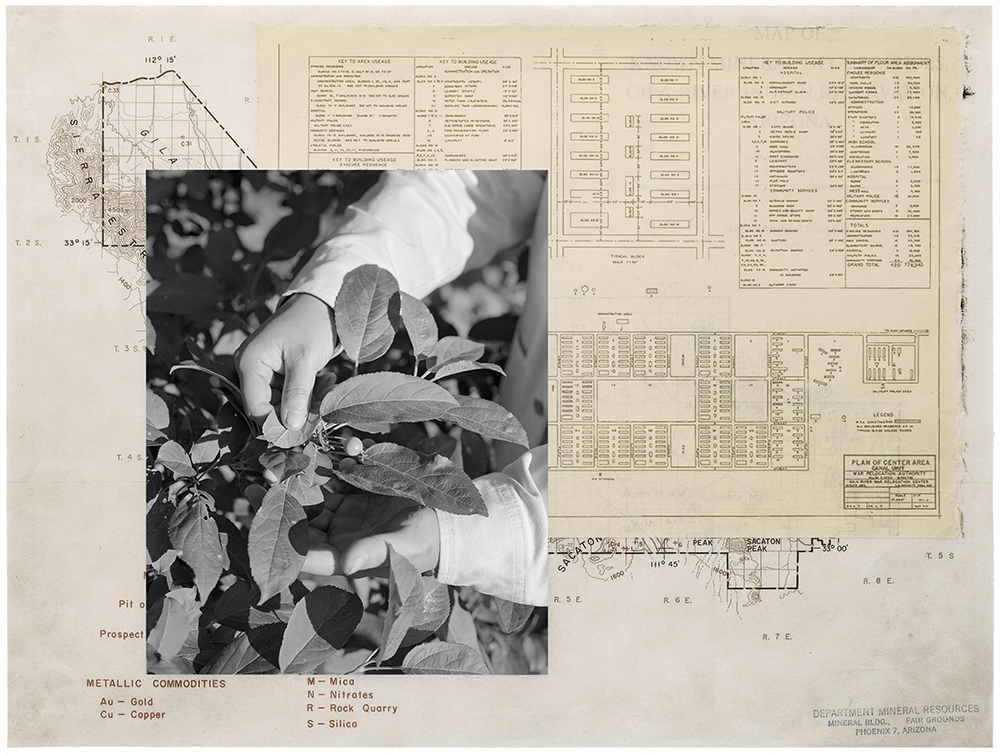

Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)

The psychic lives of Asian/Americans are mediated through histories of migration, racialization, and assimilation–three processes that produce what David Eng and Shinhee Han describe as a form of racial melancholia. Racial melancholia is a condition of the assimilated, racialized body–a collective, psychic casualty of histories of settler colonialism, racial capitalism, and white hegemony manifest as a form of self-erasure, or of loss.

This work begins to trace this type of melancholia retrospectively through time, from the present myth of the “model minority,” to American militarism and forced assimilation during WWII, to those early Asian migrants coerced into plantation labor in Hawai’i. It reflects my attempts to assemble the psychic landscape of Asian/Americans–one informed by historiographic erasures, collective unrememberings, intergenerational transmutations of trauma, and states of perpetual alienness both connected to and distinct from access to citizenship.

Materially, this work is produced from various film types and formats, original and appropriated footage, and archival objects, texts and photographs. It’s guided by scholarship in critical race theory, ethnic studies, and comparative literature, alongside tangential scrutiny of the role of canonical 20th century photographers in reinforcing processes of racialization and assimilation.

©Sydney Walsh

George Washington University

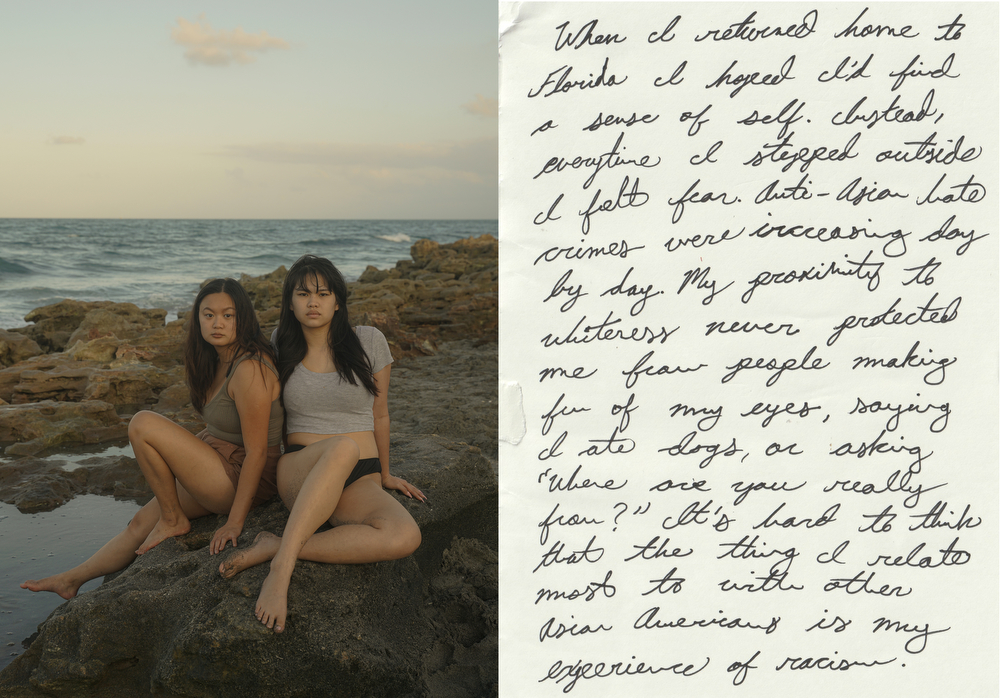

From There, To Here, shares the story of people who have experienced transracial and intercultural adoption. As a Chinese adoptee I made this project in response to how I felt growing up in a place where my cultural and ethnic background was unfamiliar to most people. One look at me and most people see that I’m Asian, and with that comes all the racist stereotypes. To the Asian community, however, since I wasn’t raised in an Asian household, I was never “Asian enough”. Because of this I struggled with my identity a lot. I still continue to be unsure of who I am. I don’t know my Chinese heritage, I don’t know my biological family, I don’t even know when my real birthday is. Some of the most basic knowledge most people have I have zero detail and context about.

Being separated from our roots as a child is something adoptees can’t control, and often leaves us asking ourselves countless questions. Since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic more questions such as “Did my biological family survive the pandemic?” and “Are they thinking about me?” have been whirling around in my mind. In a time of rising anti-Asian sentiment I’ve also come to the realization that what I relate to most with non-adopted Asian Americans is my experience of racism. My proximity to whiteness never has and never will protect me from people making fun of my eyes or asking me “Where are you really from?”

Many of us adoptees have also grown up in a world where our experiences are invalidated and silenced with the remark that we all know too well: “You should be grateful.” We never said that we weren’t grateful. The adoptee experience is often overly romanticized and seen as giving a child a new life. In reality, it’s a new life that’s completely disconnected from our personal and genetic history, leaving us with no foundation of an identity.

After recently meeting a group of adoptees who grew up with the same confusion and similar experiences as me, I realized that our stories are all too similar. It immediately became obvious that no one knew how we really felt growing up. I made this project in response to wanting to give voice to the adoption community by visually representing the bridge between my birth heritage and my upbringing in the United States.

©Kef Zheng

Maine College of Art

Using the visual language of Western media such as painting and Orientalist depictions, China Doll engages with the violence of the Western and cisnormative male gaze as it impinges upon my own body and identity as a trans and Asian artist. The series of work participates in the discussion of misrepresentations of East Asian women and calls to certain amorous stereotypes of being mysterious and exotic in nature. The title of the work breaks apart different interpretations of the phrase “China doll”. Referencing nineteenth-century porcelain dolls, the work engages with ideals of Western beauty. The term “China doll” also refers to Western stereotypes of East Asian women being submissive and subservient. Even the term “doll” alludes to both the objectification of the body, as well as the contemporary slang term claimed by the transfeminine community. This critique of Western ideals examines the intersectional overlap of objectification of the transfeminine and Asian body. The series of images contends with and subverts the cultural idea of images intended to delineate degraded forms of personhood or subjection and visual exploitation of the body. China Doll repurposes the visual structure and language of these forms of photographic subjection to engage in the paradoxical capacity of photographs to rupture the gaze of the systems which created them.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025